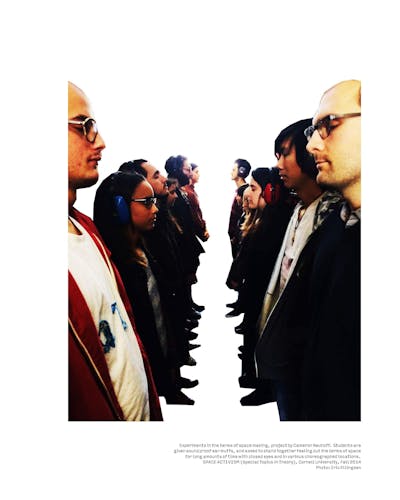

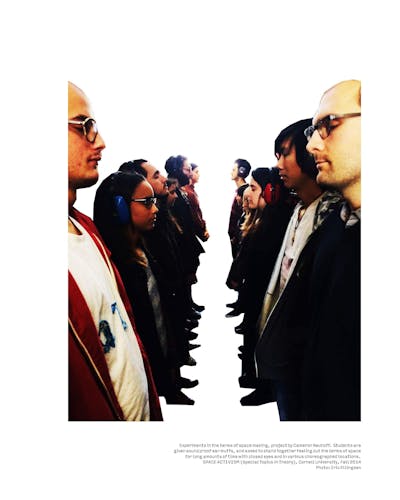

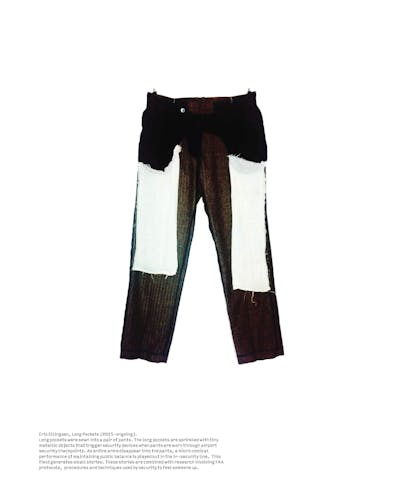

Bernadette Mayer’s poem X at Half Inch intervals was broken up into half inch intervals. These intervals were distributed to twenty architecture and landscape architecture students at Cornell University in the fall of 2014, as part of the seminar SPACE ACTIVISM. Everyone was asked to create some rule, some logical or illogical constraint by which one’s regular intervals and patterns of movement would interrupt and be interrupted with strangers in public spaces and create encounters by asking: (1) what something means and (2) where to go next. This could be compared to landscape architect Lawrence Halprin’s Motation and Take Part Processes but doesn’t have to be. As Alison Bick Hirsch says, Halprin’s goal was “to design public spaces that stimulated movement response and enhanced opportunities for choice, chance, encounter, and exchange.”

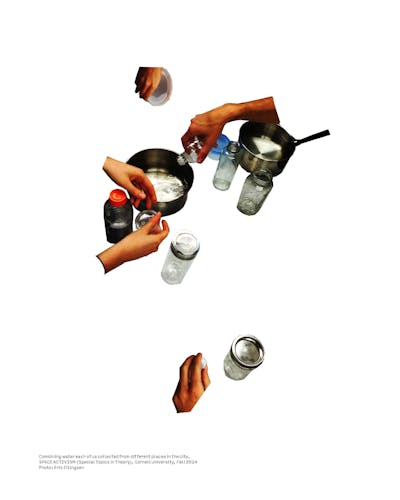

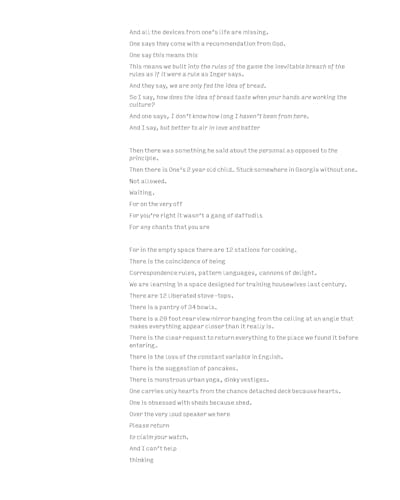

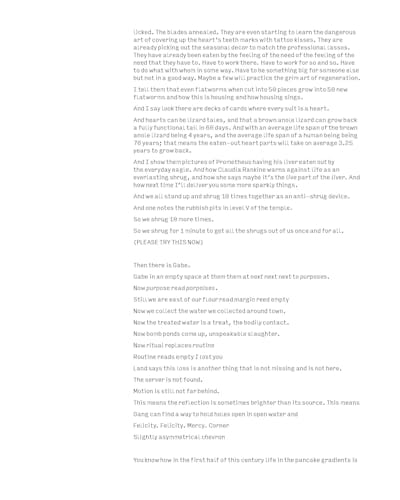

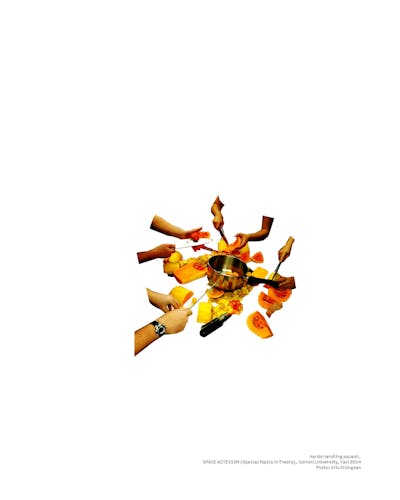

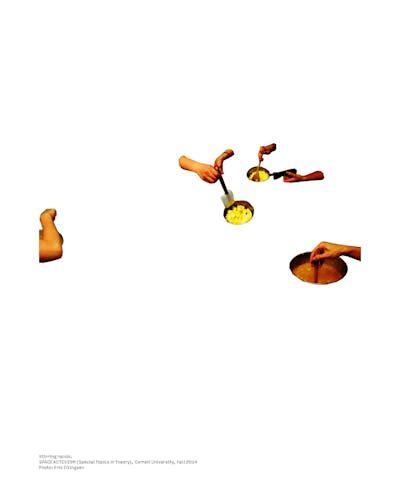

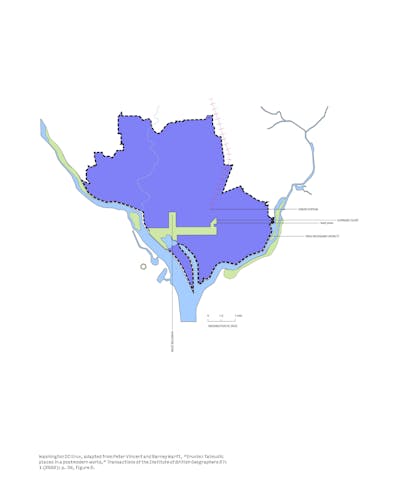

Mayer’s inched intervals became another footed interval for our walked lines of measure. We asked people to translate Mayer’s intervals from English into some other language and then, with someone else, back into English. Encounters were notated. The notations were then reported back during a dinner in which everyone was asked to bring flour, potable water collected from the city, lines of string of any length, and other interplanetary communications. We walked an ERUVIN across campus, through buildings, and into the kitchen. We mixed the parts we collected from the places we lived in with the ideas of the place we live with with the ideas of the way places could be with memories of places from the places we come from. Our flour parts were combined with a culture from Wide Awake Bakery. (In the fourteenth century, the ERUV was not only an intact boundary line designed around a ‘household’, but also consisted of baking a loaf of bread from flour collected from individual family units inside of the ERUV. Until the bread was broken, the ERUV remained intact.)

Our individual lines from Mayer’s X were twisted together in the Human Ecology building where teaching kitchens could be used to slip under university food preparation unions, liability, and contracted provider rules. In the teaching kitchens we mixed our flour, pooled and boiled our water, added the donated culture, read aloud and nibbled at excerpts of books by Daniel Spoerri to Gertrude Stein (Tender Buttons), worked out passive forms, and in general, performed the content that we were speaking about.

I have been building these translations and maps as Urban Scores since 2010. The Scores seek to engage in the materiality of language in space perception and space co-production with non-exclusive publics. In other words, in some sense, poems are taken for walks. The literal foot notes are materialized in a choreographed poetics of movement, feet, listening, and measure. The walks interfere with predetermined encounters, and irritate assumptions of institutional affinity and affirmation as to where poetry can be found, institutionalized in what journals, chap books, presses, readings, and codified in other schools of thought. Listening now becomes a central tenant of composition. And the translator must face the task of constantly having to renegotiate their own selection criteria and comfort levels by which they choose whom to engage with and where. In the processes, we are forced to ask if we actually hear what is being said, or are we only able to hear what we are ready to understand? Are we looking for something that we already know ahead of time? Do I actually ever see what you are saying?

One of the intentions of the Urban Score is to design the conditions which generate new options for perceiving the spaces we live in and the values that shape us. Another intention is simply to stop and talk and listen closely with and to different publics. And as we design filters for how to notate what is being said, we start to listen not just to what people say, but also why they might say what they say. In terms of connecting with and responding to different politics, beliefs and values on the street in shared spaces, we become mindful of how language informs world views through words as we evolve our own language as designers.

“But so far, one thing is clear to me: he’s absolutely determined to dismantle an empty, dissolve it in acid, crush it under a press, or melt it in an oven.” Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Roadside Picnic

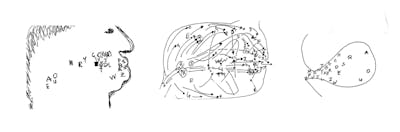

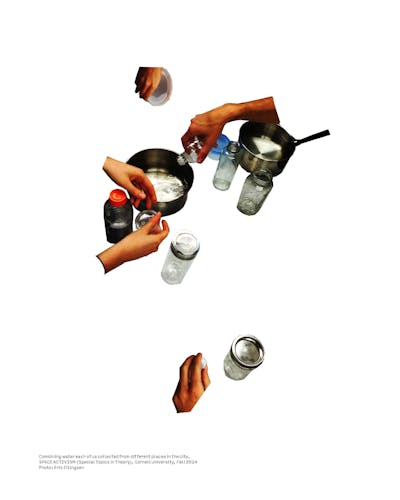

POETRY URBANISMS: spatial notations shaping volumes, RADICAL IMAGINATION COMMUNITY, from the exhibition “Outside Design,” Sullivan Galleries, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2015. Experiments selected above are based on a notational system originally conceived by Andrej Bely (Glossolalia, 1922). The drawing system requests that (1) each person slow down and say out loud each letter in a language and (2) create a notational system that attempts to capture the physiological relations which embody the production of each spoken letter. In other words, use drawing to communicate a spatial/directional relationship of places in your oral cavity where the elemental building blocks of your words are produced (teeth, tongue, lips, throat, gums, breath, etc.). Note voiced and unvoiced consonants. Increase the conscious mechanisms coordinated in the production of what you say. Attempt to feel the choreographed postures of body and air where the condensation of forces occurs in the production of sounds and in the everyday making of speech. Merely in speaking together, our words have real force. Bely scrupulously set out to understand the physical, material, and symbolic systems shaping and circulating forces in the production of sounds. In fact, Bely believed that merely pronouncing letters and words in sounds during everyday speech reproduced the harmonic forces and overtones inherent in the cosmic calculus and act of creation of the universe itself. Cosmic waves. Micro waves. Ocean waves. Sound waves. Shock waves. From clay to human to brick “breathed into” in the Judaic sense of creation. From dust to stardust to the word stardust. Bely believed that everything that moves in the universe forces the materials around them to compress and contract in a constant disturbance and contingency of waves. And, that the waves present at the Big Bang formed ruptures and rhythms as a disequilibrious continuum of spacetime—can be analyzed as sounds. And, that those sounds are identical to the sounds humans make when speaking out. Thus a precise and intentional scrutiny of the words one uses conjures the very act of creation itself. Poetry, rather than becoming an art form that defaults to descriptions and representations of the actual forces creating the universe, forces the universe into a crafted autopoesis (in the sense used by Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela) of a constant act of becoming, a constant act of creation. Bely scrupulously set out to understand the physical, material, and symbolic systems shaping and circulating forces in the production of sounds. In this way, he worked closely with Rudolph Steiner in designing the Goetheanum, a concrete acoustic chamber located in Dornach, Switzerland, an architectural oral cavity, an instrument that amplifies sound waves so as to resonate the power of speaking out. An architect, a poet, a translator, Bely thought of poetry as something ritual as something political as something historic as something divine. If you place your hand in front of your mouth and speak out, you will feel the bubbling microclimates of heat energy that your words produce. Slightly wacko, slightly mystic Bely says in his notation of the pronunciation of the German letters, Warmth is Matter accumulating, pressing from the periphery toward the firm matters of the edges the repelling fragile light the murky quartz of the center (the living flesh).

________

what the foot notes: the following people participated in some way to co-produce this urban score:

Gabriel Wilson Salvatierra, Roland Barthes (Empire of Signs: “Chopsticks”), Jordan Christopher Berta, Eric Ellingsen, Avital Ronell (in reference to Stupidity), Inger Christenson (IT), Dominique Laporte (History of Shit, trans. Nadia Benabid and Rodolphe el-Khoury), Emily Zander Chang, Jacqueline Megan Haynes, Jeremias Hollinger (artist who sings in vents, mirroring sounds in vents), Sim van der Ryn (Ecological Design), Pixar (Cars), Andrea Denise Gonzalez, Gertrude Stein (Tender Buttons), Daniel Spoerri & Robert Filliou (an anecodoted topography of chance), Ben Markus (The Age of Wire and String), Cameron David Neuhoff, Yen Hua Debra Chan, Cornel West, Euan Williams, Alfred North Whitehead (Modes of Thought), Georges Perec (‘e’), Myer Siemiatycki (“Contesting Sacred Urban Space: The Case of the Eruv,” JIMI/RIMI Volume 6), Oliver Sacks (The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat), Theaster Gates (Radical Hospitality), Megan Gran Lund, Erica C Alonzo, Bertolt Brecht (attempt), Uvedale Price (An Essay on the Picturesque), Kenneth Hoching Chow, Dong Uk Kim, Yang Chen, Doreen Massey (for space), Malgorzata Patrycja Pawlowska, Rudolf Arnheim (Visual Thinking), Stanislaus Fung (Landscape Design and the Experience of Motion; “Movement and Stillness in Ming Writings on Gardens”), Dr. Roger Sperry (Nobel Conversations), Daniel Botkin (Discordant Harmonies), Charles Wright (“Black Zodiac”), Antonio Gramsci (Prison Notebooks), Wallace Stevens (“Snow Man”), Martin Heidegger (Being and Time), Adrian Snodgrass (Thinking Through the Gap: The Space of Japanese Architecture), Gus van Sant (Do Easy), Georges Perec (Species of Spaces) & Olafur Eliasson (Take Your Time), Lynn Peemoeller, Mark Wigley (White Walls), Keller Easterling (Enduring Innocence), Ruth Webb (Ekphrasis, Imagination and Persuasion in Ancient Rhetorical Theory and Practice), Sam Fuller (director’s commentary in Tigrero: A Film That Was Never Made), James Jeremiah Slade, Veronica Velez Guzman, Aaron Samuel Goldstein, Chris Marker (The Sixth Sense of the Pentagon), Louis Sullivan (manipulated detail from A System of Architectural Ornament), George Oppen (“Of Being Numerous”), Francisco Varela (from the video What we see and what we do is not separate), Samuel Beckett (How it is), Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (The Futurist Cookbook), Nils Axen, Jakob Johann Baron von Uexküll (A Foray into the World of Humans and Animals), Andrei Bely (Glossolalia), Andrea Denise Gonzalez, Siobhan Meghan Lee, Mileva Marić, (The Love Letters), Lynn Peemoeller, Relicque Lucia Lott, Bruno Latour and Michel Serres (Conversations on Science, Culture, and Time), The Rabbi Philip Rabinowitz Memorial Eruv (http://www.kesher.org/eruv.html)

Review

By Jonathan D. Solomon

“Many of us enjoy the house of mirrors,

and there is a certain charm in the crooked streets of Boston.”

I took a walk through a city with a book. The city was Boston, and the book was Kevin Lynch’s The Image of the City—that little blue text-as-city, that collection of drawings of lines and circles and stars and arrows and questions and conclusions about form and perception and cities-as-texts. I had flown to Boston that afternoon and landed late, after the rush hour, after a rain, when the roads from Logan Airport to Cambridge were empty and the interchanges, to my Midwestern scales, so quaint and precious. The bar in my hotel had closed, as bars in Massachusetts do, so I walked out with the book in my hand, with the book in my head, across the Harvard Bridge and into Back Bay perpendicularly, and orienting axially (eschewing alleys) to Copley Square, where there is a sign for the Mass Pike that reads “New York ↓”; lines and circles and hatches and stippling, a broken bottle spreading tendrils across a manhole cover, on a corner with a stone curb, where a weak and absent boundary once met a point of confusion, referencing a bottomless tower on my way to an outside path, I began to experience shape ambiguity…

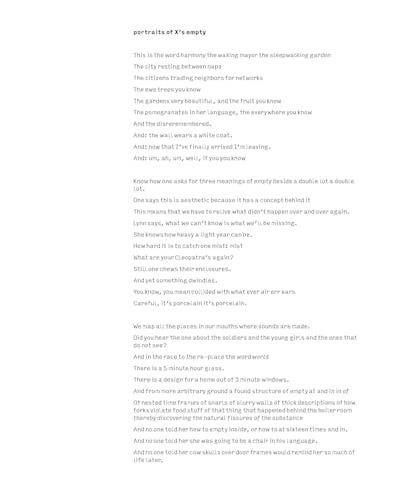

In fact I had another text in my head, Eric Ellingsen’s “portraits of X’s empty,” a poem at the edge of the boundary of the path to the node where Kevin Lynch meets David Lynch, where Situationist meets Modernologist, a text-as-city-observation, an ear-in-the-grass dérive, a “knot in a good way.”

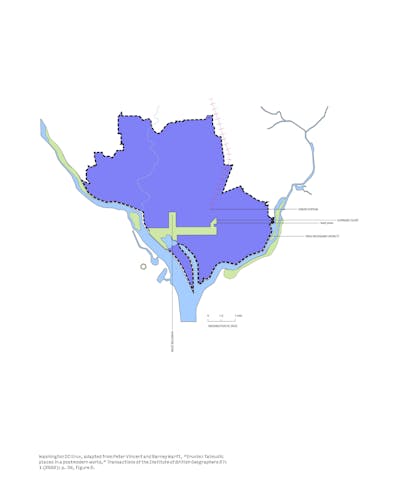

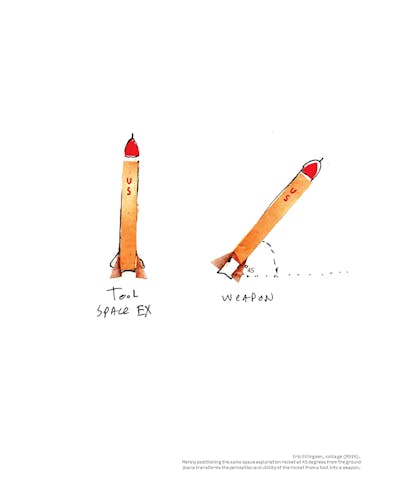

Throughout the fall of 2015, while Ellingsen was Mitchell Visiting Professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, while he was completing “portraits of X’s empty,” he drank beer while wearing boxing gloves; he built a dream machine; he lead a series walks in which participants navigated the city looking obliquely through mirrors, concentrating on their blind spots, or holding bubbles of space at the extremes of their peripheral vision; he planted garlic in gardens in the spaces between the city grid and expressway on-ramps; and, from his desk in the northwest corner of the Sullivan Galleries, on the 7th floor of the Carson, Pirie, & Scott Building, at the 0 point of Chicago’s coordinate grid, he plotted the city’s (de)centering.

Kevin Lynch as seen in the field, from the tunnel entrance: the distinctive elements cohere only in our head. Coherence is in our heads; coherence is in, coherence, says Ellingsen:

“in the pancake gradients.”

Lynch reminds us, “The image of a given reality may vary significantly between different observers,” almost as if this were a problem. Ellingsen relishes in the subjectivity of perception, and of language. To Ellingsen, cities are acts of translation. Moving in a city is an act of translation. Moving through a city, with lines of poetry in different languages, asking people to translate them, is a form of mapping. Maps are a form of poetry. Poetry is in act of urbanism.

Lynch had the right idea. We learn about the city by looking at it and drawing it, by talking with people in it, by listening to those people; by learning about the city, we become citizens, city makers. However, legibility is boring. Worse, in the city written legibly in form, no one got lost, no one had to ask directions, no one thought they had to talk or listen. In the spirit of The Image of the City, Ellingsen’s “portraits of X’s empty” reminds us that there is no writing the city, no reading the city, without getting lost in translations; “collided with what ever air err ears” to image the city, image in the city; imagine the city.

Biographies

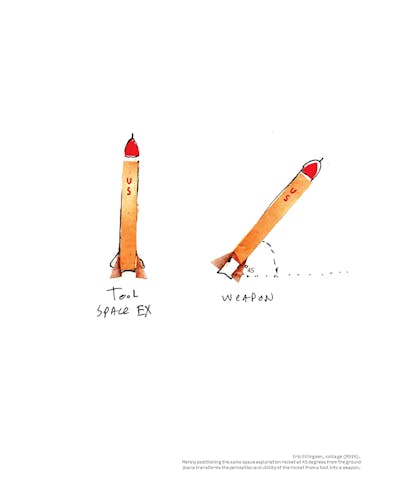

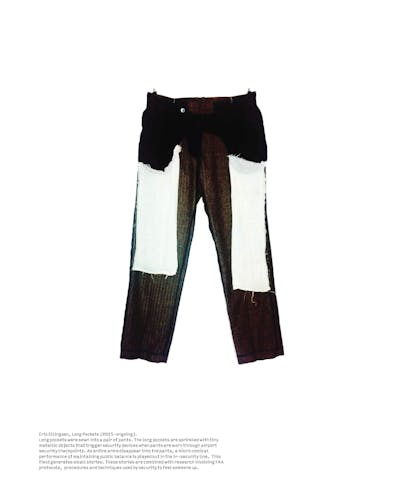

Eric Ellingsen is an Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at Washington University in St. Louis. He started Species of Space (SOS) in 2009. From 2009 – 2014, he was co-director of the Institute for Spatial Experiments, a school started by Olafur Eliasson and part of the University of Arts, Berlin. He is currently working with deans from the Art Academy and University of Iceland to create alternative, hybrid, cross-disciplinary models for MFA/engineering programs. Since 2015, he has also been working with curators at ARTbox and a consortium of international agents, as well as the municipality and mayor of Thessaloniki, Greece, on a Perceiving Academy. Ellingsen’s work focuses on pedagogy and landscape architecture as art forms. Through the design and choreography of encounters, public art installations, walks, and performances, he seeks to construct alternative ways of perceiving and using public spaces that empower communities and citizens as agents in the design and self-determination of their own spaces and lives. Ellingsen’s Urban Scores have been exhibited internationally and published in distinguished writing platforms such as Conjunctions, The Recluse, The Chicago Review, PANK (edited by Roxanne Gay), and Western Humanities Review (edited by Craig Dworkin). Email: eric@speciesofspace.com

Jonathan D. Solomon is co-editor of Forty-Five and Director of Architecture, Interior Architecture, and Designed Objects at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His writings have appeared in a wide range of publications about architecture and urbanism, such as Log, The Avery Review, Footprint (Delft), and Urban China (Beijing), and his drawings and analytical and counterfactual urban narratives are featured in Cities Without Ground (ORO, 2012) and 13 Projects for the Sheridan Expressway (PAPress, 2004). Solomon curated “Workshopping: an American Model of Architectural Practice” in the US Pavilion at the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale and “Outside Design” at the Sullivan Galleries at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His interests include extra-disciplinary, post-growth, and non-anthroponormative design futures. Solomon holds a BA in Urban Studies from Columbia University and a MArch from Princeton University. He has been a guest critic at schools of architecture worldwide and has been invited to lecture and exhibit in Asia, Europe, North and South America and Australia. Solomon has taught design at the Syracuse University, the University of Hong Kong, the City College of New York, and – as a Banham Fellow – at the University at Buffalo. He is a licensed architect in the State of Illinois, and a Member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA). Email: jdsolomon@forty-five.com