So far it has been hypothesized that all art is based on a quaternary structure where two terms are analogously equal to two other terms […] there are a number of variations within this four-part structure. We might call this the matrix of logic modes controlling the making of art.

Jack Burnham, The Structure of Art, 19731

It is not the elements or the sets which define the multiplicity. What defines it is the AND, as something which has its place between the elements or between the sets. AND, AND, AND ¬ stammering.

Gilles Deleuze and Claire Parnet, “A conversation: What is it? What is it for?,” 19772

Architect Pierre Thibault’s oeuvre interrogates the interactions, boundaries and interfaces linking architecture and landscape. Sometimes architecture is there to frame the landscape. A villa on a plateau acts as a belvedere over the expanse of one of Quebec’s immense rivers. A house turns its back to the road and extends its arms to embrace and focus the view on an intimate bay on the shore of a lake. The volumes of a country house, in the act of bridging an uneven topography, design a telescope that suggests the zooming of the gaze on far horizons. Windows strategically narrowed to the size of vertical or horizontal splits restrict the view to ribbons of landscape adroitly carved out of the surrounding scenery. Immense glass walls act as almost invisible thresholds between interior and exterior landscapes.

Now and again, landscape is used to frame architecture. The timber walls of a house in a forest are glimpsed among the branches of deciduous trees and conifers. Austere volumes, intensely white or stark black, are strikingly posed against glaring winter landscapes, or set amidst the exquisite greens of pastoral summer sceneries. A high promontory offers a perching place for a nest-like shelter. Most often, however, in the work of Pierre Thibault architecture and landscape provide a setting for each other in a synchronic conceptual and actual movement.

Landscape, besides, may surreptitiously enter or literally overrun architecture. The waters of a stream come lapping at the foundations of a villa set in a wooded area surrounded by paths covered with mosses. A treetop pierces the cantilevered prolongation of a roof. Stones, belonging to the site, step up to the house in an uneven path and merge with the wooden deck at the entrance. Coarse tree trunks become rustic columns or pilasters. The same trunks, sawed in smaller sections, are readable as sculptures. Transformed into seating places or coffee tables, they punctuate interior and exterior spaces. A fragile mosquito screen assures the comfort of a lazy, contemplative afternoon in a veranda-like space.

In turn, architecture can subtly mark or lightly set down on the landscape, making it inhabitable for a fleeting moment.

Atelier Pierre Thibault, “Les Jardins flottants” [The Floating Gardens].

White sheets, hanging from poles, flutter in the wind and draw waving lines in mutating landscapes of grass, sand, and water.

Atelier Pierre Thibault, “Territoires habités” [Inhabited Territories].

Hundreds of flittering candles trace ephemeral grids or strange constellations on the surfaces of iced lakes at night.

Atelier Pierre Thibault, “Les Jardins d’hiver” [The Winter Gardens].

Tents, performing as shelter and as lanterns, design lines on the crest of snowy hills against the backdrop of the dark, naked branches of trees in winter, or drift graciously in vast watery scenes tinted in the most tender greys, pinks, and blues at the beginning of spring.

Atelier Pierre Thibault, “Les Jardins d’hiver” [The Winter Gardens].

Atelier Pierre Thibault, “Les Jardins d’été” [The Summer Gardens].

Tiny gardens of stones, grasses, driftwoods or lights are contained in floating cubes mysteriously emerging out of crepuscular mists.

Atelier Pierre Thibault, “Les Jardins flottants” [The Floating Gardens].

The tireless questioning and exploring of the relations linking landscape and architecture in Pierre Thibault’s work consistently challenges the limits between the domains of architecture, landscape architecture, land art, performance art, and installation art. Thibault is clearly not just testing the borders between those disciplines and arts but also freely and creatively borrowing from each field. He quietly names architects and artists who, unsurprisingly, have inspired and influenced his work. In architecture, among the masters, Thibault cites Mies van der Rohe, Louis Kahn, Luis Barragan, Alvar Aalto, Gunnar Asplund, and Frank Lloyd Wright, while in the contemporary scene he points to Peter Zumthor, Sou Fujimoto, Saana, and Atelier Bow Wow together with Go Hasegawa. As for the arts, he lists Walter de Maria, James Turrell, Richard Serra, Richard Long, Donald Judd, Carl André, Joseph Beuys, and the abstract paintings of Richard Mill, a Québécois artist overtly influenced by the minimalism and the land art of the 1970s. As stated, Thibault’s listing of favorite artists and architects should not surprise even the most superficial observer of his work: all of them display precisely the same keen awareness of the fluctuating, unstable borders regulating the relations between built and un-built, land and art, landscape and architecture. Nevertheless, Thibault’s work, even if recognisably rooted in established practices, has not been received without controversies, mainly in the cases of his temporary installations.

Particularly telling is the case of the Winter Gardens realized at Charlevoix in 2001, for which Thibault received two architectural awards despite the doubts articulated by members of the juries — one Canadian, the other American — responsible for conferring the prizes. Here are some of the remarks of the Canadian jury:

Beth Kapusta: This was a very problematic project for me […] its essentially poetic program bears only the responsibility of creating delight, exempt from the fundamental responsibilities of architecture to provide “firmness” and “commodity.” Maybe I’m being a stickler for definitions, but that puts it in the realm of “art” for me, and somehow I feel it’s unfair to judge art and architecture by the same measures. […]

Mario Saia: This project in unclassifiable! It is neither architecture nor landscape architecture, neither land art nor installations nor performance. Why pigeon-hole everything when the common concern is always that of inhabitation?3

Similar observations punctuate the debate of the American jury:

Hani Rashid: So we are endorsing a land art project?

Mark Robbins: Yes.

Deborah Berke: If it’s made by an architect, what we’re also endorsing is the fact that architects can look to make their speculations and interventions beyond the limits of buildings. […]

Nathalie de Vries: It is not arty, because it actually investigates architectural stuff – like perspective and scale – and it’s not so much about metaphors.

Mark Robbins: Whether this was done by artists or architects doesn’t change our apprehension of the work and how it gets us to think about the seasons. These are always odd kinds of boundaries to define.

Hani Rashid: I think the blind boundaries thing is important for the whole awards program. We were asking earlier, why are there no parks; where does urban design start and end? And here we have it in buildings and landscape.4

The palpable undercurrent of anxiety in the above commentaries reflects a specific, and troubling, moment in time when the field of architecture, after several decades of self-inflicted autonomy, was entering a phase of expansion. Considering this shift in the realm of architecture, Anthony Vidler, in a 2005 lecture titled “Architecture’s Expanded Field,” observed that architecture at the turn of twenty-first century, like sculpture some decades earlier, had found novel formal and programmatic visions borrowing from an array of disciplines and technologies from landscape design to digital animation.5 Vidler’s title, together with the reference to sculpture, openly alluded to the 1979 canonical essay by Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” In that famous text, Krauss tried to articulate a new frame of reference for art works that began to appear in the early 1960s and that stretched the limits of the conventional definition of sculpture, defying its internal logic.

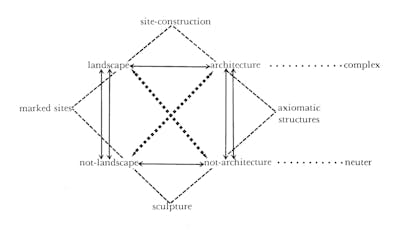

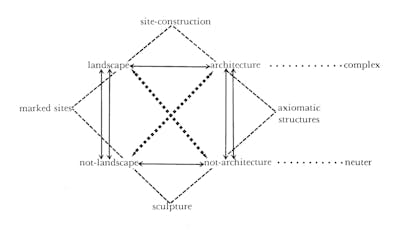

According to Krauss, sculptures were historically intended to be commemorative, monumental representations sitting in a specific place and speaking symbolically about the meaning and use of that place. With modernism, however, sculpture lost that site specificity and, consequently, its monumentality became abstract and self-referential. Modernist sculpture progressively became “something whose positive content was increasingly difficult to locate, something that it was possible to locate only in terms of what it was not.”6 This process reached its fruition when — in the works of Robert Morris, for example — sculpture attained a situation of pure negativity, defined by a neither/nor condition. In the well-known formula of Krauss, sculpture became the “category that resulted from the addition of the not-landscape to the not-architecture.”7Expressed diagrammatically, and developed according to structuralist procedures borrowed from linguistics, this definition generated the mapping of a new expanded field of “sculptural” interventions.

Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October 8 (Spring 1979), pp. 31-34; diagram on p. 38. © The MIT Press. Reproduced with permission.

In the resulting chart, we see two intersecting squares. In the corners of the first, we find the words landscape, not-landscape, architecture and not-architecture, connected by arrows that establish sets of relationships. On the second square, rotated 45 degrees, we read marked sites (physically manipulated sites or non-permanent imprints on sites), site-constructions (structures built in the landscape), axiomatic structures (intervention in architectural spaces), and sculpture. In the territories thus mapped, Krauss was able to situate, among others, the production of Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, Mary Miss, Richard Serra, Robert Irwin and Sol Lewitt. That is, she listed the artists who, in her words, had gained the “permission” to think these other forms, pushing the logic of modernism to its extreme limits, to the point of provoking a cultural rupture that signaled the advent of postmodernism. In the same essay, Krauss suggested a possible way in which a similar, postmodernist shattering of borders would invest painting. In a parenthesis, she remarkably affirms, “The postmodernist space of painting would obviously involve a similar expansion around a different set of terms from the pair architecture/landscape – a set that would probably turn on the opposition uniqueness/reproducibility.”8

Krauss’s authoritative thesis has gone virtually unchallenged for more than three decades and has inspired innumerable analogous exercises. Beyond the above-mentioned lecture by Vidler, several critics and scholars have proposed charts mapping new associations among various forms of art practice, architecture, and landscape. In fact, one of the first to revisit the four-part structuralist diagram, this time to investigate the relation of figure to ground in modernist visuality, was Krauss herself in the Optical Unconscious (1993). Four years later, Elizabeth K. Meyer explored the application of the diagram to landscape architecture in a landmark essay: “The Expanded Field of Landscape Architecture.”9 In 2007, the School of Architecture at Princeton University, in collaboration with the Department of Art and Archaeology there, organized the symposium Retracing the Expanded Field with the twofold objective of “revisiting the origins of Krauss’s essay within the context of historiographic and artistic practices of the late 1960s and 1970s, and to re-examine its status against developments in the expanded practices of art and architecture over the last thirty years.”10 More recently, the exhibition Architecture in the Expanded Field (Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco, 2012) proposed a series of contemporary installations “whose conceptual, spatial and material trajectories have produced a new and expanding network of relations between the domains of architecture, sculpture, interiors and landscape.”11 Far from exhaustive, this brief recapitulation speaks of the mesmerizing effect of Krauss’s charting on generations of artists, architects, and critics.

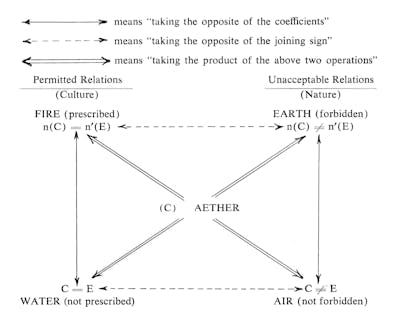

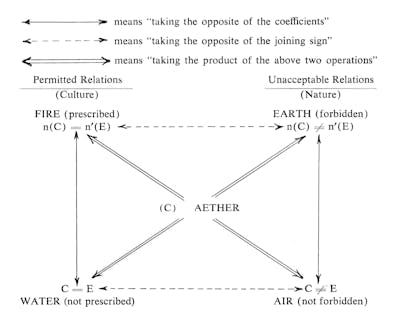

Such unanimous enthusiasm for a diagram, which appears magically to offer solutions to any sort of dilemma, raises at least some perplexity. Its origin in linguistic and structuralist thinking, for example, should provoke a number of questions. Indeed, the first to point out the limits of a structuralist approach in the field of art was Jack Burnham in The Structure of Art (1973). Possibly Krauss’s most eminent rival in the 1960s and 1970s, Burnham today is best known for a book he published a few years earlier, Beyond Modern Sculpture: The Effects of Science and Technology on the Sculpture of This Century (1968), and for his contributions as an art theorist, critic, and curator in the field of systems art. Heavily criticized by Krauss for the technological determinism of Beyond Modern Sculpture, Burnham set out to amend the “historical presumptions” and “internal inconsistencies” of this first book in The Structure of Art, where he proposed an interpretative framework derived from structural anthropology (Claude Lévi-Strauss), linguistics (Ferdinand de Saussure), semiology (Roland Barthes), and the work of the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget on cognitive development. In the third chapter of The Structure of Art, Burnham presented a “structural matrix”12 remarkably similar to the famous diagram published six years later by Krauss.

Jack Burnham, The Structure of Art, New York: George Braziller, revised edition, 1973 (first edition 1971); diagram on p. 57. © George Braziller. Reproduced with permission.

As sources for his diagram, Burnham offers the algebra sets theorems developed by the Bourbaki mathematicians, the Klein Group concepts employed by semiology, and the analogous approach used by Lévi-Strauss for defining kinship relations and mythic forms. These sources are precisely the same quoted by Krauss in her essay to explain her own diagram, down to the same bibliographical references. In her text, Krauss (who doesn’t mention Burnham’s work) managed in a masterly way to conceal one of the most blatant limits of the structuralist approach, i. e. its synchronic character and the contradictions inherent in its application to a diachronic dimension. This particular inconsistency of structuralism is, instead, artlessly underlined by Burnham, who promises in his preface to The Structure of Art to write a future book about “the perceptual laws defining the ‘historical’ sequential discernment of art.”

Beyond the constraints imposed by the synchronic nature of structuralism’s methods, a different but equally obvious flaw in structuralist interpretations has been exposed by Jacques Derrida in Given Time.13 Part of Derrida’s book is an extended commentary on the famous essay on the gift by the French ethnographer Marcel Mauss.14 Derrida explains how Mauss analyzed systems of exchange in almost a “structural” way, but without ever losing sight of the thing itself. Mauss insisted in particular on the Maori concept of hau, the spirit of things, to show how “What imposes obligation in the present received and exchanged, is the fact that the thing received is not inactive. Even when it has been abandoned by the giver, it still possesses something of him […] the hau follows after anyone possessing the thing.”15 Derrida finds this focus on the aura of the thing exchanged of the utmost interest, dismissing the critique of the role of the hau advanced by the “structural” anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss in his Introduction to the Work of Marcel Mauss.16 According to Derrida, Lévi-Strauss eliminates all the difficulties regarding the question of the thing, the intrinsic value of the gift, waving away the notion of hau and introducing a pure logic of relation of exchange. In so doing, Lévi-Strauss causes the very value of the gift to vanish. By extending this sort of criticism to the structuralist approach of Lévi-Strauss in general, one may observe that Lévi-Strauss’s diagrams succeeded in building a system of relationship but failed in defining the nature of the things the diagrams connected. Something along the same lines can be argued about the diagram around which Krauss constructed her thesis on sculpture. There, again, some of the things, namely landscape and architecture, are never really addressed.

Architecture and landscape: In Krauss’ diagram, following the well-known arrows that build sets of relationships, architecture is defined as non-landscape and landscape as non-architecture. In reading Krauss’s essay, we learn that architecture and landscape correspond also to the built and the un-built and to culture and nature. Krauss, moreover, seems to consider both of them external to the realm of art. She adds that no one, up to that point in time, had dared to think the “complex,” meaning the possibility offered by the conjugation of the two. Here is a surprising passage from her essay:

to think the complex is to admit in the realm of art two terms that had formerly been prohibited from it: landscape and architecture – terms that could function to define the sculptural (as they had begun to do in modernism) only in their negative or neuter condition. Because it was ideologically prohibited, the complex had remained excluded from what might be called the closure of Post-Renaissance art. Our culture had not been able before to think the complex, although other cultures have thought this term with great ease.17

Indeed, this statement is quite extraordinary. One may debate, as has been done for centuries, about the status of architecture as an art, but what about landscape? The latter notion, far from designating nature or the un-built, as Krauss suggests, appeared for the first time during the Renaissance to define representations in paintings and drawings of cultivated, inhabited (and built) land. During the eighteenth century, theorists of the picturesque associated it with the new art of designing landscape gardens (inspired by representations), while in the early nineteenth century the French architect, engineer, and garden designer Jean-Marie Morel proposed for his profession the appellation architecte-paysagiste, a definition later translated by Frederick Law Olmsted, who introduced the term landscape architecture to define a profession still taught and practiced in America today. Such history was clearly familiar to artists such as Robert Smithson, as indicated by his appropriation and revision of the picturesque aesthetics, and also by his admiration for the work of Olmsted.

One may argue that, beginning in the early 1960s, landscape architecture was also undergoing an identity crisis, struggling to overcome the limits of an exhausted but extremely powerful tradition that imposed the reproduction of an aesthetics (mainly bucolic, placid, pastoral scenery) that the public perceived as “natural.” Or, it may very well be that the profession of landscape architecture has always suffered, and is still agonizing, over repeated identity crises. Interestingly, in a recent essay titled “Landscape as Architecture,” Charles Waldheim (responsible for coining the term landscape urbanism) has traced the evolution of the profession of landscape architecture, reconstructing the etymology of its name in an effort to justify the multitude of scales and modes of intervention now employed in its “expanded field.”18

Quite possibly today, when we observe architects, artists, and landscape designers constantly crossing borders, borrowing forms and strategies from each other, the problem is not the inability to think the complex, the association of landscape and architecture, or infrastructure and installation, or environment and territory, but of re-thinking it. And such re-thinking should possibly include a re-writing with the emphasis on the possibility offered by the word “and” separating but no longer opposing concepts or things, as suggested in a brilliant series of texts by Gilles Deleuze.19 Deleuze explains how our thinking is an ontology, inasmuch as it is in general built around the verb “to be,” the idea of being, and how philosophy, for that reason, is full of discussions about judgments of attribution, such as “the grass is green,” and judgments of existence, as in “god is” or “landscape is.” Even conjunctions are measured in relation to the verb “to be.” But, continues Deleuze, Anglo-American empiricism has freed the conjunction, opening the possibility to reflect on relations and revealing how relations are external to their terms. Once the judgment of relation becomes autonomous, distinct from judgments of existence and attribution, it is easy to realize that it pervades everything. So, it is the “and” as opposed to the “is.” Deleuze says that, when we switch to this mode of thinking, we discover that the “and” is not just a conjunction, a connection, but it is also a relation — not just one relation, but every possible relation. The “and” is capable of throwing out of balance even the notion of being. The “and” is diversity, multiplicity, destruction of identities.

Deleuze returns to the question of the “and” at the end of the opening chapter of A Thousand Plateaus,20 Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s monumental attempt to trace a novel cartography of relations beyond the realm of State thought. Here, the “and” elucidates how the arborescent model of State philosophy could be smothered by the rhizomatic network of nomadic thinking. For Deleuze and Guattari, the rhizome, instead of offering treelike genealogies and narratives of history and culture, charts trajectories, maps poles of attractions, diagrams intensities. Rhizomatic thought doesn’t concern itself with origins and outcomes, for a “rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo.” The rhizome operates in-between, as a conjunction, as the “and.” They write: “The tree imposes the verb ‘to be,’ but the fabric of the rhizome is the conjunction, ‘and…and…and…’ This conjunction carries enough force to shake and uproot the verb ‘to be’.” The logic of “and” establishes the possibility of moving between things, overthrowing ontology, crushing foundations, nullifying endings and beginnings.

Paraphrasing Deleuze and Guattari, when we say landscape “and” architecture, we don’t mean either one or the other or that one becomes the other, because multiplicity is neither in one of the terms nor in the totality. Multiplicity is contained in the “and.” The “and” is always between the two. It operates from the middle and interrogates the sets of conditions that control the formation of statements about the relationships that associate landscape “and” architecture. From that rhizomatic middle, as Deleuze and Guattari write, things begin to accelerate: “Between things does not designate a localizable relation going from one thing to the other and back again, but a perpendicular direction, a transversal movement that sweeps one and the other away, a stream without beginning or end that undermines its banks and picks up speed in the middle.”21

Photos by Atelier Pierre Thibault reproduced with permission.

Review

By David L. Hays

In her essay “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” (1979), theorist and critic Rosalind Krauss used a diagram to categorize recent works of art that resisted classification. In expanding the terms of sculpture, Krauss enlarged the scope of that discipline and accommodated the works in question. She also inspired efforts to enlarge other practices, each by inserting new content into the given matrix. In that way, the diagram became a device for auguring more complex disciplinary futures, and its influence seemed to grow, branch, and bear fruit well beyond its initial purpose.

In “Architecture AND Landscape: Beyond the Magic Diagram,” landscape historian and theorist Alessandra Ponte argues that, having “gone virtually unchallenged for more than three decades,” Krauss’s diagram warrants careful reconsideration, in part because its origin “in linguistic and structuralist thinking […] should provoke a number of questions” and in part because Krauss’s own use of it depended on strikingly narrow definitions of architecture and landscape. For example, Krauss framed landscape as “not-built” and “natural”22 (in contrast to “built” and “cultural” architecture), assumptions in keeping with a generic sense of landscape as space beyond culture — its inevitable setting or backdrop — but overlooking deep historical associations of landscape with labor and aesthetics. Qualifying landscape as “not-built” and “natural” was — and is — like claiming that magicians make objects disappear. In fact, magicians do make objects disappear, but as an illusion based on sleight of hand — technique that obscures the technique — rather than by dematerializing them. In a similar way, landscape designers make spaces appear “not-built” and “natural” through a sleight of design — technique that obscures the technique.23 The illusion is structured in plain sight, while the unseen object (or infrastructure) remains close at hand. To those in the know, the illusion seems obvious because they understand how and where to look.

In “Architecture AND Landscape,” Ponte shows how and where to look at Krauss’s diagram, grounding its illusory power and describing a more meaningful and productive path to transformation. Hitherto, the diagram has seemed arborescent — abstract, autonomous, structural, synchronic — and, therefore, authoritative. However, in exposing Jack Burnham’s book The Structure of Art (1973) as an unacknowledged precedent to Krauss’s work, Ponte directs our attention to roots unseen or ignored. The point is neither to dwell on a slight (or sleight) of reference, nor to sanctify Burnham as the true author of the diagram, but, rather, to show that its roots are complex: doubled up, extending in multiple directions, and resurfacing elsewhere in unexpected ways. In short, they are rhizomatic.

To grasp the significance of that point, it is helpful to envision the conjunction “and” — “that rhizomatic middle” — as described by philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari and invoked in Ponte’s conclusion: “Between things does not designate a localizable relation going from one thing to the other and back again, but a perpendicular direction, a transversal moment that sweeps one and the other away, a stream without beginning or end that undermines its banks and picks up speed in the middle.”24 That way of understanding “and” transforms the content of familiar comparisons, such as landscape AND architecture, but it also pertains to instances of a single term — landscape AND landscape — and extensions thereof — […] AND landscape AND landscape AND landscape AND […].25 While the illusory power of the “magic diagram” depends on careful control of content and conjunction, both of those are fundamentally unstable, and rhizomatic thinking accommodates that. In sequencing instances of the same term, the point is neither to evacuate meaning by implying its perpetual mutability nor to essentialize it through conceptual distillation but, rather, as Deleuze and Guattari put it, “to shake and uproot the verb ‘to be’” and, as Ponte concludes, to establish “the possibility of moving between things, overthrowing ontology, crushing foundations, nullifying endings and beginnings.”

Notes

1

Jack Burnham, The Structure of Art, New York: George Braziller, revised edition, 1973 (first edition 1971), p. 56.

2

Gilles Deleuze and Claire Parnet, “A Conversation: What is it? What is it for?,” in Dialogues, translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam, New York: Columbia University Press, 1987 (original French edition Paris: Flammarion, 1977), pp. 1 – 35, p. 34.

3

Jurors Beth Kapusta and Mario Saia discussing the Special Award conferred for “Winter Garden” (Charlevoix, Quebec), in Canadian Architect, Awards of Excellence 2001, December 2001, Vol. 46, No. 12, p. 31.

4

Dialogue between jurors for the P/A award conferred to Pierre Thibault’s “Winter Gardens,” in Architecture, April 2001, pp. 114 – 5.

5

Anthony Vidler, “Architecture’s Expanded Field,” published in the conference proceedings of Architecture Between Spectacle and Use, Clark Institute, 2005, and re-published in Krista Sykes, editor, Constructing a New Agenda: Architectural Theory 1993 – 2009, New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010, pp. 318 – 331.

6

Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October 8 (Spring 1979), reprinted in Hal Foster, editor, The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, Port Townsend: Bay Press, 1983, pp. 31 – 42, p. 36.

7

Ibid.

8

Ibid., p. 41.

9

Elizabeth K. Meyer, “The Expanded Field of Landscape Architecture” (1997), reprinted in Simon R. Swaffield, editor, Theory in Landscape Architecture: A Reader, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002, pp. 167 – 170.

10

The proceedings have been published in Spyros Papapetros and Julian Rose, editors, Retracing the Expanded Field: Encounters between Art and Architecture, Cambridge (Mass.): The MIT Press, 2014.

11

Designed and curated by Ila Berman and Douglas Burnham, California College of the Arts, San Francisco.

12

The diagram includes at the center Aether and in the four corners Fire, Water, Air, and Earth. Burnham, The Structure of Art, p. 57.

13

Jacques Derrida, Given Time: I. Counterfeit Money, Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press, 1992.a

14

Marcel Mauss, The Gift: the Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies [Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétés archaïques, 1950], translated by W.D. Halls, foreword by Mary Douglas, New York/London, W.W. Norton, 1990.

15

Ibid., pp. 11 – 12.

16

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Introduction to the Work of Marcel Mauss, translated by Felicity Baker, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987.

17

Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field”, p. 41.

18

Charles Waldheim, “Landscape as Architecture”, Harvard Design Magazine 36: “Landscape Architecture’s Core?,” 2013, pp. 17 – 20.

19

Gilles Deleuze, “Trois Questions sur Six Fois Deux (Godard),” Pourparlers (1972−1990), Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1990, pp. 55 – 66. See also Gilles Deleuze and Claire Parnet, “On the Superiority of Anglo-American Literature,” in Dialogues, op cit., pp. 36 – 76.

20

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated by Brian Massumi, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987, pp. 13 – 25.

21

Ibid., p. 25.

22

See Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” pp. 36 – 37.

23

Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s design for Central Park in New York City is the best known, historic example of this practice, but it persists in contemporary projects — for example, those with planting designs by Piet Oudolf, such as the Lurie Garden in Millennium Park (Chicago, IL) and the High Line (New York, NY).

24

Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, p. 25.

25

Understood, for example, as “[…] AND space beyond culture AND cultural space AND relationship between humans and nature AND […]” but also as “[…] AND space beyond culture AND space beyond culture AND space beyond culture AND […].”

- Tags

- architecturelandscapeplaceknowledge

Biographies

Alessandra Ponte is a professor at the École d’architecture, Université de Montréal, where she teaches history and theory of architecture and landscape. She has also taught at Pratt Institute, Princeton University, Cornell University, the Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia, and ETH (Zurich). Ponte is the author of Le paysage des origines: “Le voyage en Sicile” (1777) de Richard Payne Knight (Les Éditions de l’Imprimeur, 2000) and co-editor, with Antoine Picon, of Architecture and the Sciences: Exchanging Metaphors (Princeton Architectural Press, 2003). A collection of her essays was published in 2014 as The House of Light and Entropy (Architectural Association Publications). Ponte organized the exhibition Total Environment: Montréal 1965 – 1975 (Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal, 2009) and both co-organized and co-edited the catalogue for the exhibition God & Co.: François Dallegret Beyond the Bubble (Architectural Association, London, 2011; ETH, Zurich, 2012; ENSBA-Malaquais, Paris, 2012). Since 2009, she has been responsible for the conception and organization of the Phyllis Lambert Seminar, annual colloquia on contemporary architectural topics. Email: alessandraponte@sympatico.ca

David L. Hays is co-editor of Forty-Five, Associate Head of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and founding principal of Analog Media Lab. Trained in architecture and history of art, his scholarly research explores contemporary landscape theory and practice, the history of garden and landscape design in early modern Europe, interfaces between architecture and landscape, and pedagogies of history and design. Hays is the editor of Landscape within Architecture (2004) and (Non-)Essential Knowledge for (New) Architecture (2013), both by 306090/Princeton Architectural Press. His essays have appeared in a wide range of journals — including Harvard Design Magazine, PLOT (City College of New York), Eighteenth-Century Studies, The Senses and Society (Oxford), Matéricos Perifericos (Rosario, Argentina), Tekton (Mumbai), and Feng jin yuan lin and Landscape Architecture China (Beijing) — and as chapters in numerous books. As a designer, Hays’s work explores the production of environmentally responsive objects using low-cost, low-tech materials. With particular interests in dynamic systems, environmental phenomena, and craft, his process crosses lateral thinking and intuition with grounded experiment. Email: dlhays@forty-five.com