You will find me if you want me in the garden

Unless it’s pouring down with rain

You will find me by the banks of all four rivers…

Unless it’s pouring down with rain

Einstürzende Neubauten, “The Garden,” Ende Neu, 1996

We are standing in the parliament in the rain. Following parliamentary protocol, a cold clear river crosses the floor from left to east. From the margins, basalt walls move motions at a rate of half a millimeter every week. In the midnight twilight, it dawns on us that this fluidic chamber reports to an ad hoc committee of continents and islands. As Europe and America drift physically (and politically) apart, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge admits new ground to the quorum: Tristan da Cunha, St. Helena, Ascension, the Azores. And Iceland.

And no, the roof isn’t leaking; there isn’t one. We are standing in Thingvellir, which served for nearly a thousand years as the dynamic setting for Iceland’s annual outdoor parliament. Straddling diverging tectonic plates, Thingvellir (Þingvellir, assembly field) drew citizens from across the island to discuss important matters of concern.1 Here amidst the rocky fissures of Almannagjá Gorge, divisive matters were debated in a literally dividing landscape.

While its dramatic setting, unusually large jurisdiction, and sustained duration make Thingvellir the most celebrated example, Thing parliaments in fact featured throughout Viking lands. Sites retaining names derived from the old Norse word Ting/Þing (public assembly) are found, for example, at Gulating in Norway, Tingwalla in Sweden, Tinganes in the Faroe Islands, Tingwall in Shetland and Orkney, and Tynwald on the Isle of Man.

As a landscape-based forum for discussing important community matters, Þing can be traced to the ancient Germanic proto-parliamentary Ding.2 Pertaining to a general assembly or court of law in Old High German, Dings were typically sited in topographically prominent locations that often included megaliths, large trees, or springs.3 As Martin Heidegger observed, traces of Þing and Ding are still retained in the English word thing, in the sense that a person “knows his things”; that is, she or “he understands the matters” at hand.4

Fluid parliament: the Öxará River intercepting the Thingvellir Fissure Swarm.

Image: Michal Hubert (www.mikedrago.cz). Reproduced with permission.

Yet even as Thingvellir’s parliament continued to operate within the uniquely dynamic and isolated landscape of Iceland, “things” were profoundly transforming in modernizing Europe. With the rise of the centralized state and the application of modern cartography, land enclosure eroded the feudal commons that Thing parliaments typically occupied.5 With no place left in the landscape, Things moved undercover and, eventually, within fully enclosed buildings.

As the landscape geographer Kenneth Olwig reveals, a fundamental inversion transpired. Where things once referred to landscape-based community assemblies for discussing things-that-matter, the enclosure of these forums led to things becoming reified as physical objects, or things-as-matter.6 With things now conceived more as objects than as issues, this shift also had profound implications for conceptions of landscape. Divested of its thingness, landscape became more of a receptacle for material things than a Thing itself.

Notwithstanding Heidegger’s earlier etymological lesson with regard to “knowing one’s things,” this is principally how we conceive of things today: as all manner of inanimate and unnamed objects that surround us with our own indifference. As the ultimate emblem of this ambivalence, the looming Internet of Things consigns things to hyper-networked everyday devices. In this world, landscape is relegated to a kind of Hansard that chronicles events and objects, but does not have a seat in the parliament that it once cradled: a landscape without agency, called on to smooth over the disjunctions of the industrial/digital age.

But the fissures in this arrangement are difficult to conceal. Even as we subscribe to the illusion of a seamless world in which humans and capital move without friction, the landscape is riven with more walls and divisions than ever before.7 Today, landscape functions as a scapegoat for the disjunction between the satellite’s view of mass air travel, instant communications, intercontinental ballistic missiles, and our experience on the ground, where the structures of power are sequestered behind closed doors.

All the while, beneath our feet, the environmental impacts of humans are locked into the sediment. While we have proceeded forth since the earliest civilizations as “geological agents” who reshape our environments, this activity took on a new order of magnitude in the industrial revolution.8 In our contemporary epoch, which Paul Crutzen famously labeled the Anthropocene, dust laid down in the Quaternary geological record keeps a silent score of our radiation and carbon.9 If thirty-first century stratigraphers care to dig, they will uncover a phase-shift matching in magnitude the most cataclysmic eruptions and meteor impacts. But the fascination of future scientists is of little consolation to us now; this geologic chronicle of the Anthropocene cannot be archived away, insulating us from ourselves, indefinitely.

Geological agents in the Anthropocene: terraced earthworks in preparation for suburban development, Las Vegas, Nevada.

Image: Karl Kullmann.

Parliaments of Things

And yet, things are actually not all about us. Retrieving the political agency of the landscape requires bringing all of the other things that we routinely overlook into the fold. Towards this goal, the sociologist-philosopher Bruno Latour extends agency in the Anthropocene beyond humans and the landscapes that they shape. No longer conceived as external entities awaiting human activation, non-human objects are as empowered to instigate actions as are their human counterparts. By emphasizing their interconnections, humans and non-human agents share the same shape-changing process, even if they are not always apparent, included, or willing.10

Latour applies this shared process to an object-oriented politics encompassing the many issues to which humans are connected. Typically overlooked as matters-of-fact that are incidental to political forums, objects are recast as matters-of-concern that are as important as the actual topics that are up for discussion.11 Following Heidegger, objects are thus assembled as gatherings—or things—that draw issues together, resulting in a parliament of things.

In support of this parliament of things, Latour observes that ancient landscape Things were thick not only with people but also with other things, ranging from garments to structures, cities and complex technologies to facilitate gathering. Moreover, continuing interest in Thingvellir poignantly symbolizes the extent to which contemporary political questions have become questions of nature. Yet, as Latour concedes, the shape of contemporary assemblies has changed, so we cannot simply return to ancient Things.

Although the historical transposition of political gatherings from landscape into buildings initiated this shape-shift, designing larger and more elaborate architectural domes under which to assemble offers no solution. The issue is that our political horizons are just too inflexible to accommodate the global scope of the Anthropocene. Since the astronauts on Apollo 17 first caught the lonely blue marble in the frame of a Hasselblad, it dawned on us that the whole Earth is itself a thing.12 But the inscrutable thing about the Globe is that even when we back out halfway to the moon to get it all in camera, we are unable to capture more than 49 per cent of it in one moment. That is, we are unable to see both sides of the issue at the same time — not to mention the margin between them.

This spherical vanishing act at the Earth’s horizon is a metaphor for the many other things/issues that are so vast and enduring that they defy human scales of comprehension. Global warming, nuclear radiation, and all of the non-biodegradable Styrofoam in the world are actually things, albeit ones that are massively distributed in space and time. For the philosopher Timothy Morton, these hyperobjects expose the yawning chasm between our awareness of things that matter and our limited capacity to perceive, let alone address them.13

The Earth becomes a thing: the “blue marble” as photographed by the Apollo 17 crew en route to the moon on December 7, 1972.

Image: NASA Johnson Space Center.

Strategies against architecture

Since the very nature of gatherings has changed, how might the landscape parliament be re-imaged to stretch our political horizons — to help shape contemporary matters of concern? Clearly, governments are not about to relinquish buildings and repatriate the apparatus of the State back out into the wet and windswept landscape (as a kind of recreated Thingvellir). But conversely, buildings — even enormous ones — can never truly be Things. In even the most gravity-defying modernist glasshouse, there remain too many walls and too many sliding doors through which to slip between the parallel universes of what we ought to do and actually end up doing. How then to reconcile this divergence between things that happen in buildings and Things that unfold in the landscape? That is, between things-as-matter and things-that-matter?

A few national parliaments do approach this impasse in a symbolic way with forums that aspire to be more landscape and less building. Consider Enric Miralles and Benedetta Tagliabue’s design for the Scottish Parliament, which emerges — basalt like — from Edinburgh’s geologic setting. Or, the way the bend in the River Spree cleaves through Axel Shultz’s design for the German Chancellery in Berlin, like a canyon through the bedrock. However, despite such dramatic confluences of landscape and architecture, in both cases the effect is more akin to baroque or biomorphic camouflage wrapped around conventional buildings that still keep the rain out and the politicians in.

Of the neo-landscape parliaments, Romaldo Giurgola’s design for Australia’s New Parliament House (completed 1988) in Canberra is particularly emphatic. If Oscar Niemeyer’s plan for Brasilia aspired to take flight on the wings and fuselage of its Monumental Axis, then Walter Burley-Griffin’s layout for Australia’s purpose-built capital remains firmly tethered to the ground. Situated at the heart of the city’s topographic constellation of avenues and landmarks, the new Australian Parliament is merged into a hill. The parliamentary chambers are buried beneath a publicly accessible knoll, thus placing the people above the Parliament and, by implication, not subordinate to it. Notwithstanding the reality that it must remain dry, secure, and serviceable, the Parliament seeks to express topographically the aspirations and will of all inhabitants and their interdependence with the timeless landscapes of the Island Continent.14

The people’s hill: New Parliament House, Canberra Australia.

Image: John Gollings. Reproduced with permission.

But this egalitarian gesture lasted little more than a decade. The optics and symbolism of the people’s hill were significantly eroded when security was tightened after September 11, 2001. In September 2017, a 9ft-high, welded steel palisade was erected around the hill to finish the job once and for all, sealing off the knoll — and its legislature — like a fortified medieval hill town that no longer trusts its hinterland. Much like the barricading of public space that is now necessary to repel vehicular terrorism, fencing Australia’s topographic parliament is deeply symbolic. It renders vivid a feedback loop that pushes Things further and further away, even as the ideal encapsulated in Australia’s Parliament House becomes ever more potent and relevant.

Fencing off the people from the people’s hill/fencing off the hill from the hill’s people: New Parliament House, Canberra Australia.

Image: Kym Smith/Newspix. Reproduced with permission.

Strategies against architecture II15

Using the fortification of the Australian Parliament as an example, we might imagine that a process of de-fencing needs to be deployed with some urgency. De-fencing parliaments would be a revolution of sorts, similar to dis-parking in nineteenth century Europe, which opened royal hunting grounds in and around European cities to public use by unlocking their gates and eventually (as we now take for granted in public parks) eliminating their boundary walls.16

Or not. Just as the drama of border walls between nation-states diverts our attention from far more poignant divisions, focusing on parliaments of the State is possibly a red herring: an instance of a term that continues to inhabit a semantic space, despite its meaning having mutated so profoundly that it bears no semblance of its origins. To wholly de-fence these derivative parliaments would be, quite pointlessly, to ransack them. And even the cleverest partial de/fencing strategies — that hide, for example, fences below the line-of-sight like an eighteenth century Picturesque garden ha-ha—would further cloak, rather than reveal, the issue.

Perhaps the role of landscape Things today is not to be reprised as (non-)representative parliaments for making laws, but to operate as moral shadow parliaments for discussing the things-that-matter that dithering bricks-and-mortar parliaments forfeit under weight of earmarks. Just as a renewable energy revolution is happening on the ground, effectively outflanking the hot air of political impasse, landscape shadow parliaments would, like the flow of a river, always eventually find a way around, or over, the dam wall.

With Things no longer satisfactorily represented in conventional parliaments, where might these landscape-shadow-parliaments-of-things be situated? We could argue everywhere and nowhere, in the sense that today political assembly occurs online in global forums that transcend issues, borders, and censors. But as has become evident, being untethered from time and place also allows us to insulate ourselves from divisive issues. If we feel offended, we can simply float over to other disembodied gatherings of more like-minded souls, trolling as we go.

Ultimately, even as social media outrage spins its wheels, when we really need our voices heard we still take to the streets on foot. The seamless back and forth that follows — between instantaneous online organization and temporary on-the-ground appropriation of space — embodies this contemporary form of gathering, which Latour terms hybrid assemblages.

But if these hybrid assemblages are to stick for any longer than an outrage-news-cycle, they cannot just occupy the frictionless ground of polished airport foyers and polarized online echo chambers. To stop Things from slipping away, landscape shadow parliaments need to lodge into the fissures that riddle our seemingly “closed” maps.17 Ancient Thingvellir threaded this needle, with the fissures of the Almannagjá escarpment delineating the boundary between local clans, so that the parliament occupied an interstitial every-man’s‑land over which no single group held jurisdiction.

Granted, embedding fledgling landscape forums into tectonic rift valleys, or into active no-man’s lands such as the Cypriot or Korean demilitarized zones, is highly implausible. Even the aspirations of Friendship Park, which straddles the US/Mexico border at its Pacific coast terminus, are increasingly uncertain. As one of the few tolerated places where (for a few hours on weekends) US and Mexican residents are able to interact across the border in person, Friendship Park would seem an ideal candidate for metamorphosing into a fully-fledged interstitial landscape thing.18

But painfully, its fences are too insistent, admission to its Federal some-man’s‑land too selective, and the achingly open horizons of the bordering Pacific Ocean too bittersweet. Indeed, as the semantic distinction between fences and walls becomes increasingly politically charged, the border “fence” at Friendship Park is now so thickly armored — leaving apertures no larger than a human finger — that it is in essence already a “wall.”19

Nevertheless, our everyday urban landscapes are riven with less emphatic divisions that cleave between neighborhoods, discordant land-uses, maintained and derelict landscapes, and between design visions and reality. As these rifts fester, design-triage often seeks to suture and heal the wounds. Certainly, valid circumstances for re-stitching the urban fabric may be in place, such as the removal of a downtown freeway that tore a community apart for several generations.

But in other circumstances, adjacent locales may operate according to decidedly distinct logics, such as a neighbourhood “on the other side of the tracks” that is vulnerable to gentrification when the tracks are sunken underground or removed. Wedged into these thin situations, the landscape thing potentially thickens the jump between two conditions with a third space that is neither one nor the other. The thickened thing intervenes in overlooked situations where we didn’t even realize there was an issue.20

Interstitial stitch up: Pedestrian tracks across the no man’s land of the Monumental Axis, Brasilia.

Image: © 2017 Google Earth, compiled by Karl Kullmann.

The shape of things

Given that the form of forums has changed, what shape would these interstitial-landscape-shadow-parliaments take? With shape etymologically linked to scape, the landscape imparts significant agency through its contours.21 This is emphatically demonstrated at Thingvellir, where the unique shape of the land nurtured the development of site-specific cultural practices. And although the distinctive land-shapes cleaved by dividing tectonic plates are utterly unique to Iceland, elsewhere in the Viking world Things inhabited the similarly scoured forms of postglacial landscapes. Both geomorphologies forge topographies suited to gathering matters of concern within their irregular inflections and folds.

It is no coincidence that Nordic Things remained actively decentralized for far longer in these amorphous tectonic and postglacial landscapes than elsewhere in Europe. In the dendritic landscapes more typical of Continental Europe, branching river systems support centralized control from the banks of major waterways, with tendrils of power extending upstream into the highlands.22 Here, water serves allegorically for time in the form of the inexorable flow of Modern progress and the convergence of history. By contrast, the inflections of tectonic and postglacial topographies — which are not primarily shaped by water — invoke a sense of time that flows not only in one direction, but also varies.23 This landscape-based temporal variability gives credence to the privileging of space over time in the chronicling of the Icelandic Sagas throughout a thousand years of non-linear history.24

Although we cannot slip back in time to return to ancient Things, we can conceive contemporary things as landscape inflections in place of enfenced facilities. Aside from tectonic and postglacial terrain, topographic inflections also occur naturally amidst œolian, karstic and volcanic geomorphologies. The sandy swale, the limestone sinkhole and the lava kipuka all typically absorb water down into a porous substratum before any significant convergences of land- (and time-) altering surface flows form.

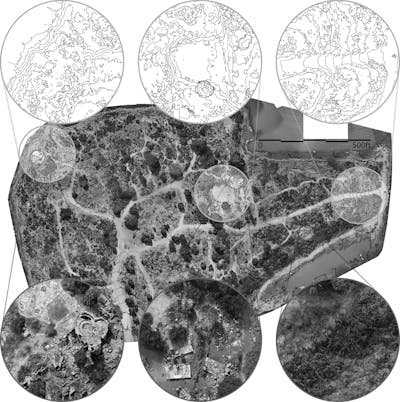

Dendritic terrain (far left) compared with inflected geomorphologies (second from left to right): sand terrain (Salton Sea, California); karst terrain (Zadar, Croatia); and volcanic terrain (Flagstaff, Arizona).

Image: © 2017 Google Maps, compiled by Karl Kullmann.

Or in the absence of these relatively uncommon landscape types, inflections can be configured. To provide context to the configuration of landscape inflections, the deep history of garden enclosure is enlightening. Customarily, the archetypal garden relies on the fence or wall as the primary demarcation device through which to distinguish cultivation from wilderness and representation from the world at large. Indeed, the etymology of “garden” invokes the condition of enclosure: in Old High German, garto means “something that is fenced in.”25

The enwalled medieval cloister garden deployed the most complete form of enclosure. Privileging the sacred vertical axis over the entanglements of the garden’s earthly context, the upper lip of the boundary wall, seen from the inside, effectively replaced the obscured, natural horizon with an internalized, artificial one.26 Over the course of early to late modernity, the garden wall was progressively deconstructed as horizons expanded and the terrestrial horizontal axis displaced the divine vertical dimension. Initially expressed as the partial openings and controlled external vistas of the Renaissance garden, the Baroque garden ultimately displaced the threshold further out towards the natural horizon formed by the curvature of the Earth.27

Fast-forward several centuries, and in today’s denatured epoch of ecological crises and genetic design, it is increasingly difficult to demarcate decisively between the garden’s representation and the wilderness from which it was hewn. Indeed, the wilderness has become the garden, in the sense that we now steward it and retreat into it just like we once did in the garden.28

If the garden’s metamorphosis through the ages sounds familiar, it is because the sequential de-fencing of the garden mirrors in reverse the enwalling of the landscape Thing. As gardens liquefied into landscape, parliaments congealed into buildings. Today, as nature and politics converge, the historical intersection of the delineation of gardens and delineation of parliaments becomes increasingly potent. Both are, after all, shaped by their horizons; the garden’s is too ambiguous, and the parliament’s too inflexible. For both, a new kind of threshold that retrieves the horizon from atop walls and from the haziness of the Earth’s curvature is required.29

Event horizons

As we comprehend it, the horizon adumbrates our field of perception and tracks us as we move across the ground, expanding as we ascend, and contracting in deference to topographically prominent features.30 With the notable exception of the horizon’s owner — who remains tethered to its focal point — objects, forces, and events pass through this horizonal threshold and into or out of play. In the sense that we perceive the future as being dispensed from over our forward-facing horizon, we merely react to these things, colliding with some of their trajectories and deflecting others, while many simply pass us by.

As was (until recently) possible atop Australia’s Parliament House, we may seek the moral high ground of a hilltop from which to better foresee and understand the expansive issues at hand. We may feel like we are on top of things, but from up on the hill our horizons defer further outwards, circumscribing more and more issues but leaving us no closer to grasping the things-that-matter.

But if we go down into an inflection, the horizon temporarily contracts to the topographic rim of the hollow. In a topographic inflection, the convention that tethers us (and other things) to the focal point of our individual horizons is dissolved. Instead of retreating unceasingly into the distance (and the future) with every step we take, the topographic horizon stays firmly tethered to the landscape. As we mill about, not only are we freed from a fixation on our own horizon, but we also share a collective horizon with everything that is gathered together within the fold.

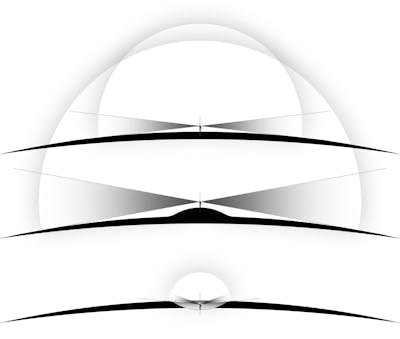

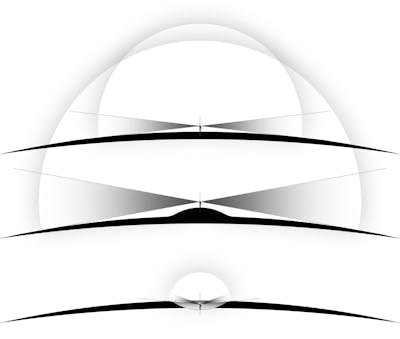

Event horizons: the horizon as formed by the curvature of the Earth from (top to bottom) on the plain; up on the hill; and down in the inflection.

Image: Karl Kullmann.

The topographic horizon that encircles the landscape inflection acts as a semi-permeable threshold that gathers things. This threshold mediates between openness and containment.31 Too open-ended and the landscape-thing is vulnerable to dissipation into the background noise of myriad other things. Too contained and the landscape-thing suffocates under the limitations placed on access and participation. And unlike the garden wall or parliamentary chamber, when the time for discussion has passed and the time for action is present, we can cross over this collective topographic threshold and leave the landscape infection in any direction.

Out there, the Earth’s horizon resumes normal operations and the wider landscape, with its myriad issues, comes back into play. Out there, we are primed to extend matters of concern beyond our preoccupation with our own present and immediate futures, which — from ecological crises to genetic design — encompass vast and miniscule scales and temporalities. And out there, the time for just thinking globally has passed. In a timely inversion of the worn-out environmentalist’s maxim (to think globally, act locally), after discussing and thinking locally, we are primed to act globally.

Drawing things together

Just as the bounding horizon traditionally distinguishes the garden’s representation of the wider world from the world itself, our political horizons also circumscribe modes of representation. Latour identifies the multiple meanings of representation as a source of ambiguity in political processes.32 In one sense, representation refers to the political and legal representation that gathers legitimated people around matters of concern. In another sense, representation refers to the technology of representation that aims for accurate portrayal of matters. And in a third sense, representation refers to the artistic representation that creatively interprets matters.

Latour zeroes in on this third form, noting that the history of painting and other artistic modes focuses on an aesthetic of matters-of-fact (objects) at the expense of an aesthetic of matters-of-concern (things).33 Across centuries of innovation in visualization techniques and technologies — from the invention of perspectival projection to the development of CAD — we have mastered the drawing of objects. And yet we remain unable to satisfactorily draw things; to “draw together, simulate, materialize, approximate, or fully model to scale, what a thing in all of its complexity, is.”34 To redress this imbalance Latour asks, “how to represent, and through which medium, the sites where people meet to discuss their matters of concern?”35

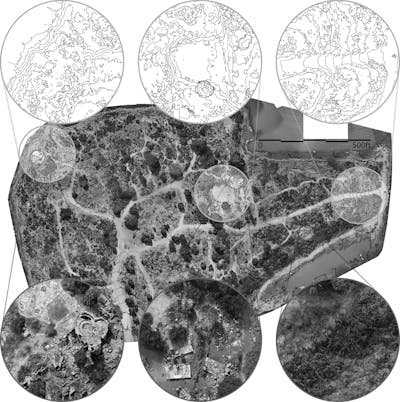

The challenge of adequately representing things is reflected in the enduring search for the substantive landscape that lies beyond its scenic representation.36 From maps to models to vignettes, the ambiguous and often contradictory nature of landscape has proven to be a slippery subject to define and represent.37 To address the technical impediments to drawing both landscape and things, we could anticipate updating Latour’s lineage of representational technologies to include today’s cutting edge apparatus. We might deploy mapping drones and LiDAR sensors for the task, on the assumption that ever-higher modelling fidelity is required to push past the object and draw forth the thing.38

Seeking things in high fidelity: 2cm resolution drone map of the Albany Bulb wasteland, San Francisco Bay, California.

Image: Karl Kullmann in collaboration with 3DRobotics.

Yet even if we capture the landscape of things from every conceivable angle, and model every speck of dust into 1:1 scale point-clouds, we would still filter things through our own hazy perceptual frameworks. To achieve a truly ecological outlook (or inlook), we require what Timothy Morton calls an immersive “zero-person perspective” that replaces the anthropocentric distance of our favored first- and third-person perspectives of landscapes and of things.39 This zero-perspective emerges from the realization that, with everything proximate to everything else amidst networks of things, there is no outside from which humans can securely observe.

Without going so far as to completely negate ourselves, we can take the zero-person perspective to mean participating in the landscapes in which we are immersed. In search of participation, gardening is one of the most immersive acts we can undertake in our environment. The garden emerges unpredictably through the shared endeavors of the gardener, the garden, and many other things, some of which are found within the garden itself (plants, worms, paths), but also less immediate things that encompass vaster scales (climate change, pesticides, genetic modification). As the gardener, we may start out with a predetermined vision, but we continually amend and adapt our designs as the garden reveals its agency over time.40 As we are assimilated into the garden, we become an immersed zero-person.

Zero person. Image: Mark Tansey, Robbe-Grillet Cleansing Every Object in Sight, 1981.

Oil on canvas with crayon, 182.9cm x 183.4cm. Museum of Modern Art (New York, NY), gift of Mr. and Mrs. Warren Brandt.

© 2017 Mark Tansey, DIGITAL IMAGE © 2017, The Museum of Modern Art/Scala, Florence.

Landscapes of uncertainty41

Both literally and metaphorically, the act of gardening illuminates something peculiar to landscape. Whereas programmatic capacity of buildings is a relatively stable concept in architecture, predetermining the usefulness of a designed (or cultivated) landscape in advance of its actualization remains an imprecise art.42 Think of landscape in terms of the weather upon which it is beholden, or in terms of the flow of the rivers that run through it. Even with continually advancing computations that virtually model (both sides of) the Earth’s weather systems, we still cannot forecast local weather conditions with any useful accuracy beyond a short time horizon. Similarly, advanced fluid dynamics modeling cannot predefine the passage of a water molecule within a river.

The uncertainty inherent in landscape also pertains to humans, who may not use a landscape in the way it was intended. In this context, placing too much pressure on landscape parliaments to perform as places for discussion may backfire by creating intimidating spaces that people avoid altogether. Indeed, the nemesis of landscape things is the Thing-parliament reconstituted as the clichéd local amphitheater that is hollow in form and function, gathering dust as an empty monument to nostalgia for community gatherings of yore.

Rather than expecting landscape things to be routinely parliamentary from the outset, perhaps their role needs to be initiated in more down to earth terms. The epidemic of people, and particularly children, who are unhealthily habituated to the indoors and who do not have regular access to stimulating landscape experiences is well documented.43 In this context, landscape things would principally just collect people, drawing them out of the Internet of things and into world of Things so that they are more likely to participate in the public realm.

Drawn together: “Sun Salutation,” by Nikola Bašić, Zadar, Croatia.

Image: Karl Kullmann.

In many situations, these contemporary proto-Things may fail to metamorphose into fully-fledged landscape parliaments. Their circumstances may simply not entertain sufficiently potent confluences of things in time and space to re-catalyze the landscape as a participatory agent of political action. But given how remarkably adept both landscape and human actors are at adapting and adopting sites and subcultures in unforeseen ways, these situations are bound to become something.

And in situations where conditions suffice and a pressing matter of concern is at hand, proto-Things should flourish. Absent the conventional apparatuses of federal, state, or local governance, at what other scales might these new landscape parliaments be dispersed? Perhaps they might draw within their horizons each of the 867 terrestrial bioregions identified across the Earth.44 Or their locations could be calibrated with projected sea-level rise, not on higher ground but to be inundated intentionally, as a wet-feet reality check on rising tides. Or they could establish niches in those ubiquitous infrastructural “buffer” zones that dissect urban landscapes but remain largely ignored. Or, as traditional zoological gardens become less and less relevant, new Things might be set within decommissioned “naturalistic” animal exhibits, thus placing them on the other side of a pressing ecological issue. In each situation, these Things — these Parliaments of Rain — might help us to more fully comprehend the things that matter.

Review

By Deni Ruggeri

Karl Kullmann’s compelling essay begins with the powerful image of a Scandinavian Þing, a landscape that served as the background of (democratic?) decision-making in pre-industrial times. The example of a place and time where geological and social fractures are mended together through democratic debating helps the author warn of our distancing from landscape as a thing-that-matters toward a landscape of things-as-matter, inanimate objects whose meaning and consequentiality are being put into question by contemporary conditions of globalization and the digital world. As is often the case, however, the truth is found somewhere in the middle.

Things-as-matter do matter. For those of us concerned with landscape democracy, things in the landscape, even the most mundane ones, matter. They help organize and choreograph our lives and act as vessels of identity and meaning. They may be objects of contention or, as Randy Hester calls them, sacred structures of inclusion, identity, and democratic life. Rather than strategizing against architecture, fences, and boundaries, the future of parliamentary Things may require the activation of processes of transformation of things-as-matter into opportunities to instigate new covenants between people and people, and between people and landscape. Rather than eschewing things-as-matter, the best path forward may be to conceive of thing-making as an opportunity to mend social fractures, inspire collective action, and imagine better futures for the earth and the people it supports.

Like the fences that separate Canberra’s Parliament from its constituents, the distinction between architecture and landscape is, in my view, a false legacy, but it has not prevented the performance of democratic life in the parliament of things. Scattered throughout the landscape of the Modernist city, abandoned shopping malls, empty parking lots, vacant schoolyards, and old freeway viaducts are being transformed into new Things for the performance of community life.

For example, in my own neighborhood of Oslo, Norway, not far from Snøhetta’s Opera House, the Losæter community gardens illustrate how the parliament of things is performing its transformative functions. Part fenced and part open, Losæter is both garden and landscape, a place in between, literally floating on a highway buried just ten years ago to make room for better natural connections. There, nature and culture blur in an indissoluble gestalt. While modern, car-based lifestyles and economics continue to flow without interruption through the Opera tunnel below, Losæter up above is activated with the type of public life and processes of the Thing. Decisions made here are seemingly mundane — such as which tomato plant grows best, which soils might be most productive, or which ancient grain might be able to perform better in the cold Norwegian landscape — but their horizon connects the community of citizen farmers and visitors to larger matters of resilience, adaptation, and the sustenance of human life.

Whereas the Oslo of things-as-matter has tended toward gentrification and densification, electric cars and congestion charges, the people of Losæter are making Things with meaning in growing organic and sustainable crops, while also building community. For example, as residents gather to bake bread and exchange food preparation practices, social justice is being redefined through new interactions/dialogues between old and new citizens and the performance of rituals celebrating people’s renewed connection to the natural world.

What role may landscape architects play in the evolution and transformation of our cities from parliaments of things into landscapes of Things that matter? And what new and old knowledge and expertise might be necessary to envision how the future landscape might look and perform? Designing and planning the landscape of Things will not be, as in the past, the work of few, powerful people and their experts. Landscape transformations will require full and rich participation, and partnerships between experts and citizen scientists, activists, and entrepreneurs investing their hearts and stewarding the landscapes of Things-that-matter for generations yet to come.

Notes

1

Agust Gudmundsson, “Tectonics of the Thingvellir Fissure Swarm, SW Iceland,” Journal of Structural Geology 9: 1 (1987): 61 – 69. Richard Beck, “Iceland’s Thousand Year Old Parliament,” Scandinavian Studies and Notes 10: 5 (1929): 149 – 153.

2

Kenneth R. Olwig, “Liminality, Seasonality and Landscape,” Landscape Research 30: 2 (2005): 259 – 271.

3

Barbara Dölemeyer, “Thing Site, Tie, Ting Place: Venues for the Administration of Law,” in Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, eds., Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005), 260 – 267.

4

Martin Heidegger, “The Thing,” in Martin Heidegger, Poetry Language Thought, trans. Albert Hofstadter (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1971), 161 – 180: 173.

5

Kenneth R. Olwig, “The Jutland Cipher: Unlocking the Meaning and Power of a Contested Landscape Terrain,” in Michael Jones and Kenneth Olwig, eds., Nordic Landscapes: Region and Belonging on the Northern Edge of Europe (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 12 – 51. Álvaro Sevilla-Buitrago, “Urbs in Rure: Historical Enclosure and the Extended Urbanization of the Countryside,” in Neil Brenner, ed., Implosions/Explosions (Berlin, Germany: Jovis Verlag, 2014), 236 – 259.

6

Kenneth R. Olwig, “Heidegger, Latour and the Reification of Things: The Inversion and Spatial Enclosure of the Substantive Landscape of Things — The Lake District Case,” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 95: 3 (2013): 251 – 273: 256. Reification refers to the process of something abstract becoming real in a physical or material sense.

7

Refer to Karl Kullmann, “Route Fittko: Tracing Walter Benjamin’s Path of No Return,” Ground Up (Delineations) 5 (2016): 70 – 75.

8

Anne Whiston Spirn, The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1984), 91.

9

Paul J. Crutzen, “The “Anthropocene”,” in Eckart Ehlers and Thomas Krafft, eds., Earth System Science in the Anthropocene (Berlin & Heidelberg, Germany: Springer 2006), 13 – 18.

10

Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2005). Bruno Latour, “Agency at the Time of the Anthropocene,” New Literary History 45 (2014): 1 – 18. Bruno Latour, “Which Protocol for the New Collective Experiments?,” (2001), http://www.bruno-latour.fr/node/372.

11

Bruno Latour, “From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik or How to Make Things Public,” in Latour and Weibel, Making Things Public, op. cit. (see note 3), 4 – 31: 9, added emphases.

12

On the cultural impact of the whole earth image, see Denis Cosgrove, Geography and Vision: Seeing, Imagining and Representing the World (London, England: I.B. Taurus, 2008), chapter 1.

13

Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 1

14

Except that the First Australians have never identified with or felt included in the narrative of the people’s hill. The Aboriginal Tent Embassy that has occupied the lawn at the foot of Australia’s Houses of Parliament for almost half a century demonstrates this glaring exclusion. Incidentally, as the fastest moving continental plate on Earth, Australia is plowing northwards and slightly to the east at a rate of 7cm per year.

15

With apologies to Einstürzende Neubauten’s 1991 album of the same name.

16

The archaic verb dispark means to “divest a park of its private use” by “throw[ing] parkland open.” See Charles Talbut Onions, ed.), The Shorter English Dictionary on Historical Principals (Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1964): 530.

17

The “closure of the map” refers to the claiming of (nearly) all of the land on Earth by nation-states, leaving the twentieth century without terra incognita. However, while “the map” may be officially “closed” from the hegemonic and spatially exclusive perspective of Western cartography, in many instances it was never open to begin with. For example, in the case of European “settlement” of Australia, the British legal definition of terra nullius conveniently overlooked the pre-existing mappings of the indigenous residents.

18

For in depth explorations of the Mexico/US borderlands, refer to Michael Dear, “Imagining a Third Nation: US-Mexico Border,” Ground Up (Delineations) 5: 46 – 55. See also Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books, 1987).

19

Although walls capably defended communities for thousands of years, by the sixteenth century medieval fortifications were increasingly ineffective against new ballistic developments. As the Renaissance star forts of northern Europe exemplify, strategically shaped, horizontal defensive earthworks supplanted vertical defensive masonry. In the twentieth century, both were consigned to irrelevance as long-range ballistics materialized from over the horizon in every unanticipated direction. As the world folded in on itself, life retreated underground, making the final defensive shield the thickness of landscape itself. It is no surprise then, that the return of border walls has revived some decidedly medieval devices for their circumvention in the form of ladders, catapults, and tunnels.

20

Refer to Karl Kullmann, “Thin Parks/Thick Edges: Towards a Linear Park Typology for (Post)infrastructural Sites,” Journal of Landscape Architecture 6: 2 (2011): 70 – 81.

21

Scape derives from the Dutch suffix schap, which, like the German suffix schaft, refers to shape. See Edward S. Casey, Representing Place: Landscape Painting and Maps (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), and Kenneth R. Olwig ““This is not a Landscape”: Circulating Reference and Land Shaping,” in Hannes Palang, Helen Sooväli, Marc Antrop, and Gunhild Setten, eds., European Rural Landscapes: Persistence and Change in a Globalising Environment (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004), 41 – 65.

22

“Continental Europe,” as used here, excludes the Scandinavian Peninsula.

23

See Bernard Cache, Earth Moves: The Furnishing of Territories (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1995).

24

See Kirtsen Hastrup, “Icelandic Topography and the Sense of Identity,” in Jones and Olwig, eds., Nordic Landscapes, op. cit. (see note 5), 53 – 76. Here I am co-opting the title of Manuel De Landa, A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History (New York, NY: Zone Books, 1997).

25

See Bernard St-Denis, “Just what is a garden?,” Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes 27: 1 (2007): 61 – 76; Peter Marcuse, “Walls of Fear and Walls of Support,” in Nan Ellin, ed., Architecture of Fear (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997), 101 – 14; and John Dixon Hunt, Greater Perfections: The Practice of Garden Theory (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000).

26

Rob Aben and Saskia de Wit, The Enclosed Garden: History and Development of the Hortus Conclusus and its Reintroduction into the Present-day Urban Landscape (Rotterdam, The Netherlands: 010 Publishers, 1999).

27

Allen S. Weiss, Unnatural Horizons: Paradox and Contradiction in Landscape Architecture (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998).

28

Refer to William Cronon, “The Trouble with Wilderness,” in William Cronon, ed., Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co., 1995), 69 – 90.

29

For a more in-depth account of garden horizons, refer to Karl Kullmann, “Concave Worlds, Artificial Horizons: Reframing the Urban Public Garden,” Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes 37: 1 (2016): 15 – 32.

30

Refer to James J. Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1986).

31

For this concept of “open containment,” I am drawing on the work of Arakawa and Gins. Refer to Shusaku Arakawa and Madeline Gins, Architecture: Sites of Reversible Destiny (London, England: Academy Editions, 1994).

32

Latour, “From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik or How to Make Things Public.”

33

Ibid.

34

Bruno Latour, “A Cautious Prometheus?,” keynote lecture for the Networks of Design meeting of the Design History Society, Falmouth, Cornwall, September 3, 2008: 12, added emphases.

35

Latour, “From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik or How to Make Things Public,” 6.

36

Refer to Kenneth R. Olwig, “Recovering the Substantive Nature of Landscape,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 86: 4 (1996): 630 – 653.

37

Refer to Karl Kullmann, “Hyper-realism and Loose-reality: the Limitations of Digital Realism and Alternative Principles in Landscape Design Visualization,” Journal of Landscape Architecture 9: 3 (2014), 20 – 31.

38

Refer to Karl Kullmann, “The Satellite’s Progeny: Digital Chorography in the Age of Drone Vision,” Forty-Five: Journal of Outside Research 157. http://forty-five.com/papers/157

39

Timothy Morton, “Zero Landscapes in the Time of Hyperobjects,” Graz Architectural Magazine 7 (2011): 78 – 87.

40

As Robert Harbison observes, a gardener “takes what is there and begins to bend it to his will, but it is always getting beyond him.” Robert Harbison, Eccentric Spaces (New York, NY: Knopf, 1977), 4. For a more in-depth account of the designer as gardener, refer to Karl Kullmann “The Garden of Entangled Paths: Landscape Phenomena at the Albany Bulb Wasteland,” Landscape Review 17⁄1 (2017): 58 – 77.

41

For an exploration of this topic, refer to the inaugural edition of the University of California, Berkeley journal Ground Up (Landscapes of Uncertainty) 1 (Berkeley, 2012).

42

Refer to Karl Kullmann, “The Usefulness of Uselessness: Towards a Landscape Framework for Un-activated Urban Public Space,” Architectural Theory Review 19: 2 (2015): 154 – 173.

43

Refer to Billie Giles-Corti, Melissa H. Broomhall, Matthew Knuiman, Catherine Collins, Kate Douglas, Kevin Ng, Andrea Lange, and Robert J. Donovan, “Increasing Walking: How Important Is Distance To, Attractiveness, and Size of Public Open Space?,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 28: 2 Suppl 2 (2005): 169 – 176.

44

As defined by the World Wide Fund for Nature.

Biographies

Karl Kullmann is a landscape architect, urban designer, and associate professor at the University of California, Berkeley, where he teaches courses in landscape and urban design, theory, and digital delineation. Kullman’s scholarship and creative work explore the urban agency of the designed and discovered landscape. He has published widely on this area through diverse lenses, including topographically calibrated urbanism, taxonomies of linear landscapes, re-imagining the enclosed garden, strategies for landscapes of decline, landscapes of (dis)orientation, frameworks for landscape uselessness, and various angles on techniques and technologies of landscape imaging, representation, mapping, and data-scaping. This research is actively applied through design practice, with built, urban, landscape projects in China, Australia, and Germany and numerous design competition prizes and exhibitions. Email: karl.kullmann@berkeley.edu

Deni Ruggeri is an associate professor in the Institute for Landscape Architecture and Spatial Planning at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, where he is also co-director of the Centre for Landscape Democracy. Before joining NMBU, he taught in the USA for over a decade, including at Cornell University and the University of Oregon. Ruggeri’s research, publications and teaching focus on socio-ecological dimensions of landscape and urban design. He is particularly interested in the influence landscapes have on people’s place identity and attachment and in developing new tools to promote more sustainable lifestyles, physical and mental well-being, ecological health, economic viability, identity, delight, and biophilia in neighborhood settings. Ruggeri has practiced landscape architecture in California (SWA Group) and Colorado (Design Workshop). He has international experience leading community design and visioning processes and has served as an advisor for the European New Town Platform in Brussels. His work has received funding from the US Department of Agriculture, the European Commission, the EU Interreg IV program, and the Cariplo Foundation (Italy), among other sources. Ruggeri holds a Ph.D. in Landscape Architecture from the University of California, Berkeley, graduate degrees in both Landscape Architecture and City Planning from Cornell University, and a Laurea in Architettura from the Politecnico in Milan, Italy. Email: deni.ruggeri@nmbu.no