Without being deterministic, accessible imaging technology wields considerable agency in the evolution of architectural, landscape, and urban discourse. In the 1920s, the proliferation of the airplane and the drafting machine respectively inspired and facilitated the modern architectural project. In the 1970s and 1980s, the ubiquitous photocopier was a key technology enabling the sampling, scaling, and compositing that permeated the development of postmodern theory. With digital technology crossing a critical threshold in the 1990s, discourse fell ever more into lockstep with technological innovation. Advances in the usability, manipulability, and processing power of three-dimensional modeling applications were central to the rapid shift from deconstructivism to biomorphism.

In the 2000s, pervasive satellite imagery — initially through Ikonos™ and later through Google Earth™ — facilitated the interpretation of cities as organic systems.1 Characterizing urbanism in ecological, rather than formal, terms ultimately led to the establishment and influence of landscape urbanism within architectural discourse. Roughly synchronously, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), which had hitherto been the domain of specialists in geography, gained more user-friendly interfaces, attracting experimentation within the spatial design disciplines. Coupled with increased availability of spatialized data, this technology was instrumental in the renaissance of mapping, which the design disciplines had neglected for three decades.2

In its many forms, integrated mapping based on widely accessible satellite imagery and satellite-derived spatial data continues to influence contemporary discourse vigorously. The proliferation of Global Positioning System (GPS) enabled smart phones has thus far supplemented, rather than disrupted, the presence of the satellite’s overarching gaze in design theory.3 This is probably because, although smart phones dispense a wealth of interconnected location-specific data, the fidelity of this information principally suits interpretation at the metropolitan, rather than local, scale. That is, while these devices are calibrated to plot our precise location in space, they are less proficient at telling us about our immediate sense of place.

The drone’s eye

Recently, imaging technology has shifted nearer to the ground as drones — the miniaturized progeny of satellites — saturate altitudes below 400ft.4 Gyroscopically-stabilized multi-rotor unmanned aerial vehicles have been available to consumers since 2009 and have reliably carried high definition cameras since 2012.5 In addition to this now familiar optical utility, drones are also purposed as micro-freighters, with experimental payloads including merchandise and humanitarian aid delivery, seed and insect dispersal, and fire ignition and suppression. In an extreme payload up-scaling, a British hobbyist travelled in a tethered swarm of 54 drones, with the homemade space-frame reminiscent of the Wright brothers’ first efforts.

Although this brief manned drone flight encapsulates our persistent desire for a personally (re)affirming overview of our environment, the propagation of drone technology has primarily followed a less embodied trajectory. The evolving third generation of consumer drones includes two features that are potentially significant to design discourse and urban culture in general. The first is automated navigation, which includes both the ability to predefine virtual flight paths and the capacity to autonomously track the ground-dwelling “pilot” from the air. Automated navigation also enables the second novel feature, whereby topographic features (including buildings and landscapes) are optically recorded in overlapping detail and converted through stereophotogrammetry into orthorectified and georeferenced three-dimensional maps.

Relinquishing direct control over avionics frees drone users to image the landscape methodically in all its roughness and detail. Although this is in itself a potentially groundbreaking contribution to the democratization and individualization of mapping, the self-tracking capacity most personifies third generation drones. When aimed obliquely down and across at the user, drones become personal mirrors in the sky, enabling operators to witness themselves in the third person, acting out their lives within the near landscape. Consequently, just as we turned the eyes in smartphones back onto big brother and eventually back onto ourselves, drones as personal appliances of vanity increasingly usurp drones as insidious instruments of institutional surveillance.6

Notwithstanding ongoing cultural reticence towards the surveillant capacity of drones, the likely widespread adoption of this technology raises stimulating questions for architecture, landscape, and urbanism. What are the implications when the duality of the immersive, horizontal, eye-level view and zenithal satellite’s gaze is dissolved? How will this low-aerial vantage impact our imaging and cognitive mapping of urban environments that, since the eighteenth century, have primarily been presented to us planimetrically? How will the third person view alter how urban actors conceive of their own sense-of-place in the city? And what new techniques for representing and imaging the city will the drone’s perspective initiate or induce?

Third person urbanism © 2016 Karl Kullmann

In framing these questions, this essay anticipates the transformative agency of the drone’s‑eye view in design discourse. This potential is premised on three characteristics that distinguish drone-based imaging from satellite-derived imaging and mapping. (1) Interstitial detail: Although the clarity of satellite imagery continually improves, the sheer distance and the largely orthogonal perspective limits this perspective. The drone’s eye is capable of extreme proximity and accessing the underneath and in-between spaces that remain hidden from orbit 450 miles above the earth. (2) Near real-time control: The rapid speed of the low earth orbits required for detailed imaging limit satellite imagery capture to small preset windows. Web-based satellite imagery is also automatically filtered to privilege aesthetically palatable imagery over less pastoral imagery that may nevertheless reveal more important information about a particular site.7 In contrast, although their navigation systems remain tethered to geostationary satellites, drones enable direct spatial and temporal control over imaging. (3) Content creation: Designers engaged in mapping generally operate as miners, samplers, and filterers of satellite, aerial, and spatial data provided by agencies and corporations. Drones facilitate direct — and usually on site — user engagement in the creation of optical and photogrammetric content.

The bird and the satellite

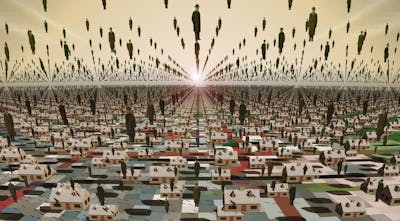

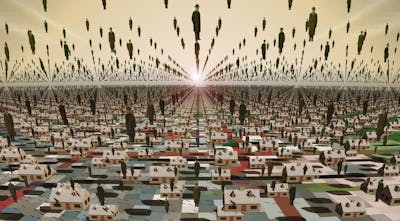

From hilltops and cathedrals to camera-equipped balloons, kites, pigeons, airplanes, and, ultimately, satellites, the eye in the sky has traced a century and a half of increasingly higher, more systematized, and more vertical aerial vision. Marking a return to lower and more individualized oblique viewpoints, the drone’s eye interrupts that progression. Precursory momentum for this reversal is reflected in the recent reemergence of the bird’s‑eye view in contemporary media and online map applications.8 The revival of this anachronistic angle reveals limits to modern cartography’s capacity to represent coherently the contemporary post-urban landscape and render legible the scale of everyday life.9 From orbit, we lose track of our place within seemingly undifferentiated urban agglomerations, which appear naturalized in their resemblance to bacterial blooms. When zoomed right in, familiar features registered in planimetric forms often fail to resonate with our established perceptions of our place within our world.10

Cities as bacterial blooms © 2016 Karl Kullmann

However, just as drone-based imaging remains technologically intertwined with satellite systems, the revived bird’s‑eye view supplements, rather than substitutes for, the vertical (nadir) view. The symbiotic relationship between drones and satellites and between oblique and nadir views suggests potential for addressing the limitations of modern cartography through novel hybrid map-representations. Enabled by two interlinked aerial imaging platforms operating at divergent scales, these novel maps seek the dual remit of conveying both the qualities of a place and the overall structure of the city. In doing so, they potentially address Fredric Jameson’s standing call for a new aesthetics of cognitive mapping that enables the situational representation of the individual within the vaster totality.11

Although now three decades on, Jameson’s challenge to combat loss of perceptual orientation in the postmodern city remains relevant to contemporary urbanism. Indeed, this continued significance is demonstrated by the recurrence of data-scaping/mapping examples that explicitly or implicitly lay claim to addressing the terms of Jameson’s call. Enabled by the increase in spatial data, these visions seek innovative and enigmatic windows into the invisible city-structuring webs of information and energy. The “shimmering” cartography that results substitutes solid and fixed identities with flows, change, and relational differences.12 But, while effective at illuminating informational convergences within the vaster totality, urban data-mapping projects generally apply a very abstract threshold to the situational component of Jameson’s new aesthetic of cognitive mapping. “Situational” is interpreted more comprehensively here as representation that acknowledges its own selective and incomplete point of view and includes richness, diversity, and a degree of material immediacy.13 While significantly diminished in modern cartographic conventions, these situational characteristics are reflected in chorographic mapping practices.

Analogue chorographies

In Claudius Ptolemy’s classical ternary representational hierarchy, chorography is the most grounded of the three modes of the natural order.14 Chorography is situated below the Euclidean projections of geography and the grand structure of the (geocentric) universe as established by cosmography. Revived following the fifteenth century Latin translation of Ptolemy’s Geographia, the remit of chorography is the local region, where it registers features at the near scale in which human life takes place. The Greek root chôra/choros denotes a definite piece of ground, a place. Of the three representational orders, this root positions chorography closest to the modern usage of landscape (which traces Germanic etymology).

Unlike geography, which eschews likeness for the abstraction and precise location of features, the near scale of chorography permits a qualitative and sensory approach to the representation of the particularities of the landscape. Moreover, whereas quantitative geographical methods seek to eliminate the vagaries of interpretation, chorography admits the creative contribution of the individual mapper. This is embodied in the common practice of depicting the mapper in the third person within the representation.

Nevertheless, chorography remains more map than painting. Chorographic representations from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries contain both quantitative and pictorial information about land. Map space is scaled and proportioned according to a complex scaffolding of traverses and offsets or triangulations, whose constructions are often superimposed into the representation. However, unlike the cartographic pursuit of Euclidean consistency, chorographic constructions do not seek to depict all features equally. Despite this elasticity, chorography fulfills the original sense of surveyable space, where the surveyor is situated within the same space that is being mapped.

Renaissance chorographic survey of a region. From Leonhard Zubler, Fabrica et vsvs Instrvmenti chorographici: qvo mira facilitate describuntur regiones & singulae partes earum, veluti Montes, Vrbes, Castella, Pagi, Propugnacula, & simila, trans. Caspar Waser (Basel, Switzerland: Ludovici Regis, 1607), fig. 12. Creative Commons License 2016, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Library.

Although initially displayed alongside geographic projections, chorography was usurped beginning in the eighteenth century by the more spatially consistent military cavalier projections and, eventually, by the plan.15 As cities and land-holdings extended well beyond the horizon — and could no longer be seen in their entirety from cathedral towers or hilltops — the problem of establishing both limits and continuity rendered the scope of chorography inadequate. In its place, geography filled the role of urban delineation through the mathematical division of the earth’s surface from overhead. Precision supplanted resemblance, as the zenithal plan-view ascended over time to represent the rational order of modern city planning.16 Relinquished of the duties of measurement and topographic representation, chorography devolved into the scenic city-branding panoramas that were popular in the nineteenth century and still frequent tourist maps today.

Digital chorographies

Jameson clarifies that novel situational/totality mappings should avoid returning to the traditional machinery of a “reassuring perspectival or mimetic enclave.”17 Given this caveat, how then is a reinterpreted chorography potentially relevant in the twenty-first century? Moreover, how is a reinterpreted chorography — which is material by definition — pertinent in the context of dematerialized urban imaging where GPS-satellite and cell phone towers have supplanted bricks-and-mortar landmarks? The rationale for re-potentializing chorography is grounded in the continued relevance in the digital/drone age of several traditional chorographic characteristics. These characteristics are explored here through three interrelated motifs: (1) elastic projections; (2) patchwork stitching; and (3) situated sensing.

Motif 1: elastic projections. Although quasi-perspectival examples are common in the historical record, the perspectival construction of space is neither a precondition nor an ambition for chorographic representation. Unrestrained by a perspectival or projective standard, chorography is analogous to a highly malleable camera lens that continuously changes viewpoints.18 This intrinsic elasticity is pertinent to both spatial cognition and drone technology.

Spatial cognition research has established the non-mimetic eccentricities of our individual cognitive maps. In Kevin Lynch’s renowned 1960 imaging study of select US cities, this distortion was methodologically purged from the results.19 Stretched and superimposed across a standard Cartesian map of each city, the spatial wrinkles of the subjects’ individual mental maps were ironed out. By contrast, Denis Wood’s 1973 study of distance perception between London landmarks conserves and integrates the subjects’ elastic spatial cognition.20 The nonlinear perceptions of distances are interpolated onto the city to create a series of warped maps that represent each urban actor’s psycho-geography. In this regard, Wood’s study extends the Situationists’ creative exploitation of the gap between the situational experience of a city and the rigidity of traditional topographic maps.

Representation of individual subjects’ warped spatial perceptions of London landmarks © Denis Wood. First published in Wood, I Don’t Want To, But I Will (Ph.D. dissertation, Clark University, 1973; Worcester, MA: Clark University Cartographic Laboratory, 1973); reprinted in Wood, “Lynch Debord: About Two Psychogeographies,” Cartographica 45: 3 (2010): 194, fig. 11. Reproduced with permission.

Spatial elasticity appears to be an integral factor that enhances, rather than destabilizes, urban imaging. Nevertheless, as is evident in both Wood’s warped maps and the cartographic fragments and flows of the Situationists, Cartesian plan projections poorly accommodate elasticity. In order to retain the integrity of the underlying matrix, amplification in one part must be offset elsewhere with compression or erasure. In contrast, chorographic space does not require balancing within a universal structure. By following an internal system, the bespoke constructions and limited ranges of chorographic maps are more conducive to expressing elasticity.

Chorographic elasticity is also reflected in drone mechanics. Unlike the stable and predictable glide of satellite arcs, drones are buffeted around in the low atmosphere like insects. As the electronic gyroscopes, magnetometers, pressure sensors, accelerometers and sonar avoidance systems scramble to keep the device aloft, the camera captures raw imagery through a continuously variable viewpoint. Although post-processing software is tasked with neutralizing as much of this variability as possible, the physical pre-process of capturing raw imagery literally embodies the highly malleable notional camera lens of chorography.

Motif 2: patchwork stitching. As distinct divisions between the cultural and natural landscape dissolved over the centuries, the problem of limits and continuity diminished the effectiveness of chorographic mapping. Read on their own terms, individual chorographic maps provided useful representations of delineated landscapes. However, assembling numerous overlapping, elastic, disjointed or distinctive chorographies into a coherent whole proved far more challenging than the unlimited seamless spatial coverage offered by geography. Whereas chorographic maps reach their limits at a forest, ridge, or horizon, geographic (Cartesian) maps are circumscribed only by the immaterial map frame, which can be infinitely extended, rescaled and tessellated.

Contemporary techniques for integrating large quantities of disparately angled images into coherent configurations suggest a technological solution to the longstanding historical problem of chorographic continuity. Digital stitching deploys algorithms to establish commonalities between images with overlapping fields of view. Typically, when used to create photographic panoramas and orthomosaics of satellite and aerial imagery, the technique employs blending to provide the illusion of a seamlessly smooth transition between the constituent parts. Omitting this final step in the stitching process retains the integrity of the seam (edge). When applied to chorography, stitching seams along overlaps upholds the internal distinctiveness of each map.

In principle, digital stitching facilitates the compositing of personal digital chorographies, which are captured through many uncoordinated individual drone excursions and composited into a digital patchwork. Over time, the accrual of digital chorographies onto this thickened patchwork suggests an overlapping multi-layering process that is analogous to accumulated leaf litter on a forest floor. In this metaphor, each crumpled leaf represents a physiognomic digital chorography of a particular terrain that is situated loosely amongst myriad other chorographic leaves. En masse, those leaves are not intrinsically fused into a single authoritative map. Rather, the vestiges between chorographies offer a multitude of overlapping angles on places — over, under, and in-between.

Lorna Barnshaw, “Replicants,” reproduced here to invoke conceptually the crumpled physiognomy of an individual chorography

© 2015 Lorna Barnshaw. Reproduced with permission.

Motif 3: situated sensing. If the Global Positioning System has every feature on earth triangulated to within a few feet, what purpose do maps serve? On one hand, Cartesian mapping continues toward the goal of assembling a virtual duplicate of the world. Facilitated by highly integrated GIS systems and achieved by expunging evidence of its own method of construction, the simulacrum map exists independently of the reality to which it originally refers. This type of mapping continues to fulfill the conventional roles of geographic recording, spatial location and navigation. On the other hand, just as nineteenth-century photography released painting from mimetic responsibility, the release of postmodern mapping from geographic obligation unlocked a surge of creativity in the medium. Maps adopted a multitude of forms that stretch normative cartographic definitions, including experiential and immersive expressions of everyday life-space and instruments of resistance and subterfuge.

The divergence of mapping as mimesis and mapping as expression is reflected in the distinction between practices of site (in situ) observation and remote sensing. While site observation came to be associated with the immediate and subjective, the oversight provided by (satellite and aerial based) remote sensing became established as the more objective position.21 Indeed, the confidence invested in the accuracy of remote sensing is now so complete that the traditional cartographic practice of ground proofing maps through site observation has been largely abandoned. Although in part a result of the sheer quantity of mapping data now being generated, the neglect of ground proofing signals a deepening disconnection between the map as a virtual construct and concern for the terrain to which it pertains.

The activities of site observation, ground proofing, and — indeed — chorography fulfill the original sense of survey, whereby the surveyor is situated within the space being mapped. From that position, the surveyor gains direct sensory contact with the site/subject. Working from the inside out, the surveyor constructs a spatial representation feature by feature until sufficient geometric and topographic information has been catalogued to gain a theoretical elevation over (but not high above) the landscape. In spatial cognition terminology, this situation equates to survey knowledge, which indicates advanced comprehension of the configuration of one’s environment.22

Drawing on chorography’s historical connection with surveying, digital chorography suggests a platform for re-assimilating the strategic advantages of top-down, airborne sensing with the grounded, inside-out fieldwork of site observation. The drone’s eye facilitates this re-assimilation; the near-ground aerial position combines the benefit of suspended proximity for situated near-ground proofing with the extended range of the aerial realm that is currently the established domain of remote sensing. The situated sensing suggested by this position enables the simultaneous representation of both scales of Jameson’s new aesthetic of cognitive mapping.

Recovering nearness

The drone’s‑eye view extends our personal horizons to situate us in the near landscape. Correlating this situated nearness within the vaster urban structure impels new/old forms of mapping, which, I have argued, takes the form of re-potentialized digital chorography. Certainly, when we first create a digital chorography, our attention will invariably fixate on the surveyors (ourselves) situated within the map. But, once this third person vanity is satisfied, our attention will turn to the near landscape, which fills out part of the map. In doing so, the era of third generation drones may be less narcissistic than typically anticipated, as the drone’s‑length placie (portmanteau of place and selfie) supersedes the ubiquitous arm’s‑length selfie.

Recovering nearness through digital chorography does not imply nostalgic retreat into the singular point of view of a sedentary sense of place. Nor is nearness constituted as a mere textural backdrop for the multiple points of view of perpetual nomadism. Rather, it is a combination of both sense of place and perpetual movement. Movement, whether embodied (physical) or virtual (through representation) amplifies the sense of place. For example, ports, although highly fluid, are nevertheless customarily very well defined places. Given that we move places so frequently — every five years on average in the US — we, like ports, are both fluid and fixed.23 Cognitive imaging is the mechanism by which we integrate this new nearness into a more comprehensive image of the city.

The return to the near scale that drone-based digital chorography affords also potentially serves as a catalyst for other developments in the design disciplines. After two decades of emphasis on large-scale associations, systems, and infrastructures, the drone’s eye may enhance interest in retaining and incorporating the incumbent near-scale qualities latent in many wasteland sites. The revival of observation as a legitimate design method is another potential byproduct. This, by extension, suggests the renovation of environmental psychology, which stalled during the 1970s due to the limitations of its blunt, analogue tools. When coupled with recent advances in neuroscience, it is conceivable that environmental psychology will follow a digitally-propelled renaissance within design discourse similar to the one undergone by mapping a decade ago.

This is not to claim that burgeoning interest in the drone-scape will jettison the discursive agency of satellite imagery and mapping. On the contrary, we are now so habituated to using satellite images and maps as extensions of our persons — their systemic abstraction is so seductively useful — that the orbital view will remain fertile territory for design.24 Therefore, just as drone navigation is integrated with satellite systems — and both the near and far integral to urban imaging — we can assume discursive coexistence between the two scales.25 Positioned within this alliance, drone imaging possesses characteristics capable of transforming how we image our urban environments. This is significant because how we image — and hence map — our present urban environments influences how we physically shape them over time.

Review

By Conor O’Shea

Two contrasting categories of landscape architectural practice stand out today: high-profile public parks in city centers and investigative design research projects. The first consists of mainstream realized works usually conceived in response to RFPs or competition briefs.26 In those, practitioners fulfill a service role and have little to no real influence on location, purpose, or funding. Works in the second category seek to change the built environment using innovative design research methods. They often reframe the urban through large-scale mapping, selective use of satellite imagery, and sophisticated diagramming. Representing landscape is put forward as a first step towards reimagining and reshaping it.

While many contemporary urban parks lack the imaginativeness of investigative design research, the latter often does not go far enough to propose implementable design strategies.27 Why is that?

Karl Kullman’s paper “The Satellite’s Progeny: Digital Chorography in the Age of Drone Vision” suggests a possible way forward. In it, Kullman links drone imaging to the older practice of chorographic mapping, an ancient but neglected, place-based method of representation. Drone chorography is a way to recover “nearness,” which could be a useful tool for contemporary design researchers seeking to engage with the realities of place, including territories neglected by modernism and recently engaged by landscape architects. As Kullman writes, “[a]fter two-decades of emphasis on large-scale associations, systems, and infrastructures, the drone’s eye may enhance interest in retaining and incorporating the incumbent near-scale qualities latent in many wasteland sites.”

Can drones push the investigative landscape architectural design research project closer to making real change? Kullman argues that drone chorography will have significant impact on the future of design because “how we image […] our present urban environments influences how we physically shape them over time.” That is no doubt true, but it is also something we have heard often from design researchers. Stopping short of actionable approaches reinforces a disconnect between practitioners and academic design researchers. Through my experience in both categories of work, I have become aware of the paucity of speculative urban visions that are both well researched and actionable.28

Could drone chorography help the aspiring design researcher come closer to making an impact? My own recent groundtruthing of Class I railroad intermodal freight facilities with the aerial cinematography and analysis company Modus Collective29—fieldwork I would have previously carried out using Google Earth and a ZipCar — confirms the benefits that Kullman invokes. Nevertheless, human-to-human interviews, community outreach, political engagement, and research-based design strategies matter more than ever. Drone imagery is a powerful tool of persuasion, and it can help us reframe sites marginalized by mainstream urban discourse, but what the world needs, more than ever, are rigorous design researchers who not only wield tools to reimage the urban, but who have the capacity to reshape it, too.

Notes

1

The ecological agency of satellite imagery was preceded by the influence of WWI aerial photographic interpretive techniques on the development of the modern science of ecology. See Peder Anker, Imperial Ecology: Environmental Order in the British Empire, 1895 – 1945 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2001).

2

In the 1960s, the use of transparent film overlays practically curtailed the effectiveness of Ian McHarg’s original method of “suitability mapping.” Although suitability mapping contributed to the development of GIS, the specialized nature of this software influenced its adoption by geography and estrangement from the design disciplines.

3

Current estimates place a GPS receiver in the hands one third of the world’s population.

4

As mandated by the Federal Aviation Administration, 400ft is the maximum flying altitude for drones in the US.

5

In addition to gyroscopes, drones also depend on a range of other sensors, including magnetometers, pressure sensors, accelerometers, sonar/radar avoidance systems, and GPS.

6

The catch is that, when the content captured by our phones and drones is intercepted, harvested, or aggregated, we (un)wittingly partake in a society of outsourced self-surveillance. Although techniques are available for disconnecting a range of devices (aka “going black”) while maintaining their utility, dependence on interconnected systems makes disconnecting drones more problematic.

7

Clement Valla, “The Universal Texture,” Rhizome (July 31, 2012). http://rhizome.org/editorial/2012/jul/31/universal-texture/

8

Georeferenced, orthorectified, oblique, aerial photography includes Bing Bird’s Eye™ and Google Maps 45°™.

9

This disjunction is memorably explored in Michel De Certeau’s juxtaposition of the tactically immersed Manhattan pedestrian against the strategic “Concept-city” as witnessed from the 110th floor of Two Word Trade Center. Michel De Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1984).

10

Wilfried Wang, “On the Representation of Agglomerative Structures,” Daidalos 61 (1991): 106 – 107. William J. Mitchell, The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1992).

11

Since cognitive mapping is by definition the internal neurological representation of spatial information, we can assume that Jameson uses the term here to refer to mapping of/for cognition, thereby incorporating the agency of representation. Fredric Jameson, “Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capital,” New Left Review 146 (1984): 83. See also Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991).

12

Marcus Doel, Poststructuralist Geographies: The Diabolical Art of Spatial Science (Lantham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1999). See also Nadia Amoroso, The Exposed City: Mapping the Urban Invisibles (London, UK: Routledge, 2010).

13

Franco Farinelli, I segni del mondo: immagine cartografica e discorso geografico in età moderna (Scandicci: Nuova Italia, 1992). Per: Ola Söderström, “Paper Cities: Visual Thinking in Urban Planning,” Ecumene 3: 3 (1996): 249 – 281.

14

In the historical summation of chorography that follows, I draw on Herman Moll, The Compleat Geographer: or, the Chorography and Topography Of all the known Parts of the Earth (London: Printed for Awnsham and John Churchill … and Timothy Childe, 1709); Lucia Nuti, “Mapping Places: Chorography and Vision in the Renaissance,” in Denis Cosgrove, ed., Mappings (London, UK: Reaktion Books, 1999): 90 – 108; Edward Casey, Representing Place: Landscape Painting and Maps (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2002); John Pickles, A History of Spaces: Cartographic Reason, Mapping and the Geo-Coded World (London, UK, and New York, NY: Routledge, 2004; Denis Cosgrove, Geography and Vision: Seeing, Imagining and Representing the World (London, UK, and New York, NY: I.B. Taurus, 2008); and Kenneth R. Olwig, “Has ‘geography’ always been modern?: choros, (non)representation, performance, and the landscape,” Environment and Planning A 40 (2008): 1843 – 1861.

15

Cavalier perspectives were precursors to axonometric projection. See Yve-Alain Bios, “Metamorphosis of Axonometry,” Daidalos 1 (1981): 41 – 58.

16

Tanis Hinchcliffe and Davide Deriu, “Eyes over London: Re-Imagining the Metropolis in the Age of Aerial Vision,” The London Journal 35: 3 (2010): 221 – 224.

17

Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, 54.

18

Nuti, “Mapping Places: Chorography and Vision in the Renaissance,” 90 – 108.

19

Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1960).

20

Denis Wood, “Lynch Debord: About Two Psychogeographies,” Cartographica 45 (2010): 185 – 199.

21

Notwithstanding infamous geopolitical misinterpretations of remote imagery that changed the course of history.

22

Reginald G. Golledge, ed., Wayfinding Behavior: Cognitive Mapping and Other Spatial Processes (Baltimore MA: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998).

23

Ian Nairn, The American Landscape (New York: Random House, 1965).

24

Laura Kurgan, Close Up at a Distance: Mapping, Technology, and Politics (Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 2013).

25

From a technical perspective, the zone of overlap for this aerial imaging coexistence currently covers about 100 acres. Beyond that dimension — with consumer drones practically limited by battery life and line of sight requirements — airplanes and satellites still prevail.

26

For example, Brooklyn Bridge Park, New York, NY (Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, 2003-ongoing); Millennium Park, Chicago, IL (SOM, completed 2004); and Central Waterfront, Toronto, Canada (West 8, 2007-ongoing).

27

Some exceptions include “A Sustainable Future for Exuma,” at Harvard University, OPSYS, directed by Pierre Bélanger, and P‑Rex at MIT, directed by Alan Berger.

28

The notion that, “showing the world in new ways, unexpected solutions and effects may emerge” from James Corner’s seminal essay “The Agency of Mapping” inspired a resurgence of mapping and aerial photography as research tools by a generation of landscape architects. (James Corner, “The Agency of Mapping: Speculation, Critique and Invention,” in Mappings, ed. Denis Cosgrove (London, England: Reaktion Books, 1999), 217.) However, in framing this same quote, Hille von Seggern argues that the transition from research into design remains mysterious: “In the design and planning of environments, it is by no means clear how we get from an examination of the existing situation and knowledge of the originating conditions to the design idea. Often, this is treated almost as if it were a secretive skill. Similarly, it is not self-evident in the spatial design disciplines that the examination of the existing situation and the generation of ideas are creatively interwoven.” (Hille von Seggern, “Understanding=Creativity: Designing Large-scale Urban Landscapes,” in Exposure, eds. Marieluise Jonas and Rosalea Monacella (Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne Books, 2012), 66. While the onus is not always on the design researcher to enact physical design, offering strategies is useful. For example, in his book Drosscape, Alan Berger photographs and maps marginalized developments in North America as the basis for landscape architectural speculation. He concludes by offering “strategies for designing with drosscapes” to designers engaging with marginalized urban sites. (Alan Berger, Drosscape: Wasting Land in Urban America (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006), 239.)

29

See Conor O’Shea, Luke Hegeman, and Chris Bennett, “Logistical Ecologies of the North American Operational Landscape,” MAS Context 28: Hidden (Winter 2015): 8 – 35. http://www.mascontext.com/issues/28-hidden-winter-15/logistical-ecologies-of-the-north-american-operational-landscape/

Biographies

Karl Kullmann is a landscape architect, urban designer, and associate professor at the University of California, Berkeley, where he teaches courses in landscape and urban design, theory, and digital delineation. Kullman’s scholarship and creative work explore the urban agency of the designed and discovered landscape. He has published widely on this area through diverse lenses, including topographically calibrated urbanism, taxonomies of linear landscapes, re-imagining the enclosed garden, strategies for landscapes of decline, landscapes of (dis)orientation, frameworks for landscape uselessness, and various angles on techniques and technologies of landscape imaging, representation, mapping, and data-scaping. This research is actively applied through design practice, with built, urban, landscape projects in China, Australia, and Germany and numerous design competition prizes and exhibitions. Email: karl.kullmann@berkeley.edu

Conor O’Shea is a landscape designer and urbanist, founding principal of Hinterlands Urbanism and Landscape, and an assistant professor of landscape architecture at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. O’Shea holds post-professional Master of Landscape Architecture and Master in Design Studies: Urbanism, Landscape, and Ecology degrees from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and a Bachelor of Landscape Architecture degree from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Before beginning graduate study, O’Shea was a designer and project manager at Hoerr Schaudt Landscape Architects in Chicago, IL. From 2014 to 2016, he was a Visiting Assistant Professor in the Master of Landscape Architecture program at the Illinois Institute of Technology. O’Shea’s work as Hinterlands has been widely recognized through publication, exhibition, and important awards. His collaboration with Kees Lokman and Fadi Masoud received First Place in the international “Network Reset: Rethinking the Chicago Emerald Necklace” competition (2011). Hinterlands’ “Logistical Ecologies” was featured in the “BOLD: Alternative Scenarios for Chicago” section of the 2015 Chicago Architecture Biennial. Email: ceoshea@illinois.edu