Greenhouse at the Frick (Pittsburgh, PA) in fog. Film still from Elise Adibi, Respiration Paintings (2018), by Elise Adibi and JPC Eberle.

From April to October 2017, a selection of my abstract oil paintings was exhibited together with plants in the historic greenhouse at the Frick, a museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. With its elevated heat and humidity, a greenhouse is an unusual location for paintings, especially works like mine made with vital substances: essential plant oils on canvas and human urine on copper. Part animal, part vegetal, part mineral, my paintings were already hybridized in material terms, but the fertile conditions in the greenhouse induced them to transform at accelerated rates and in unexpected ways. Sharing affinities with plants, fungi, and insects, not to mention sunlight and humidity, the paintings embodied a new kind of agency and life cycles different from what they would have had in conventionally conditioned spaces aimed at keeping them formally stable.

The greenhouse at the Frick was designed in 1897 by Alden and Harlow, an architecture firm known for its significant cultural commissions, including the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (also in Pittsburgh) and City Hall in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Frick museum is named after the family to whom the property belonged originally. These were the same Fricks who eventually moved to New York City and whose home there became another museum, the Frick Collection. Henry Clay Frick made his fortune turning coal mined in the nearby mountains into coke, a material necessary for the production of steel. He sold much of his coke to the steel manufacturer Andrew Carnegie, who took Frick on as a partner in 1882. The Fricks moved into their Pittsburgh mansion in 1883 and called it “Clayton” as a play on Henry’s middle name. The greenhouse was used primarily to grow flowers for their new home. As the Fricks’ wealth increased and their estates multiplied, cut flowers were transported eastward by train to their other homes in New York and Massachusetts.

Visitor entering the exhibition. Film still from Elise Adibi, Respiration Paintings (2018).

Around the same time when the first iron and steel greenhouses were being built in the mid-1800s, the term “greenhouse effect” came into use to describe the impact of gases that trap infrared radiation in the atmosphere, keeping Earth’s temperatures constant. One of the primary greenhouse gases is carbon dioxide, which was then being produced at sharply increasing rates due to the burning of fossil fuels, such as coal, and has since increased to a critical level in the earth’s atmosphere. Coal is a rock formed from dead plant matter converted into peat millions of years ago. When Frick’s greenhouse was built, it was as yet unknown that increased carbon dioxide would lead to global warming.

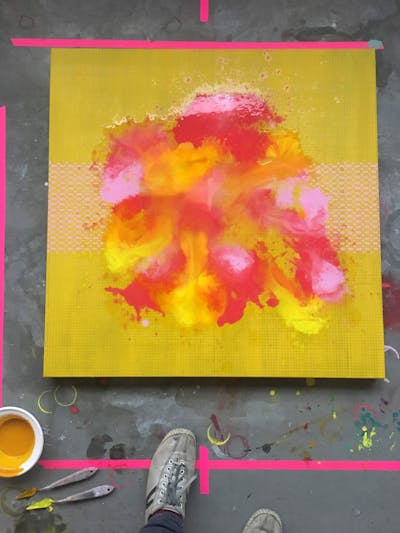

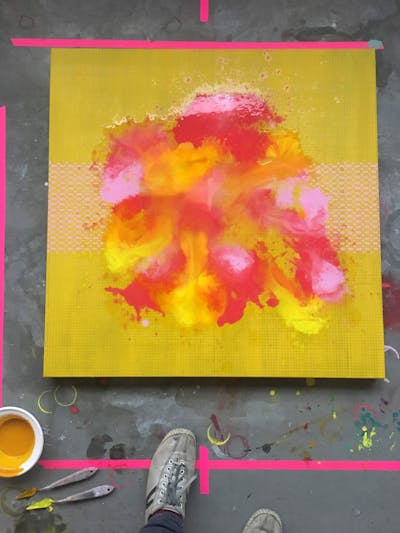

Yellow and Pink Pour Painting (2017). Rabbit skin glue, graphite, oil paint, and essential plant oils of lemon, Peru balsam, red mandarin, and ylang ylang on canvas, 30 in. x 30 in. Photo by Elise Adibi.

The idea to display paintings in a greenhouse grew out of my use of essential plant oils in making my own paints. Essential oils are typically used in natural perfumery and, medicinally, in aromatherapy. Researching the oils and their various properties, I learned that what we call oil painting is, in fact, plant oil painting. Around the 15th century, painters started mixing dry pigments with plant oils. This invention has historically been attributed to artist Jan van Eyck, who was also known to be an alchemist, and that latter interest may have influenced his experimental attitude towards natural materials, including plant matter. Plant alchemy was practiced as a form of herbal medicine, and tinctures created from distilled plant matter were used as remedies. So, the same substances used to heal were also used to paint, and that connection persists even today. For example, linseed oil, the most common binder in contemporary oil paints, is pressed from flax seeds and is edible. In its food grade form, it is called flaxseed oil, and people ingest it as a source of alpha-linolenic acid, an omega‑3 fatty acid believed to have a wide range of health benefits.

French marigolds in front of Copper Monochrome (2017). Rabbit skin glue, oil paint, and copper on linen, 30 in. x 30 in. Photo by Elise Adibi.

As I became increasingly invested in using essential plant oils in my paints, my research led me to the plants themselves. I read about plant communication and learned that trees and other plants release pheromones to ward off predators and to warn other plants of impending danger. They also use these airborne molecules to attract pollinators, thereby spreading their own genes. Learning about plant communication, it occurred to me, was I somehow communicating with the plants when I was painting? I was breathing in scents that have evolved as a form of communication in the natural world, but since I am not a pollinator, what messages — if any — might the plants be communicating to me? Aromatic molecules first entered my nasal passage, then proceeded to the olfactory bulb in my forebrain, where the information was processed and sent to other parts of my brain. In other words, plant molecules were entering my body physically and possibly affecting my thoughts, moods, and memories. During long hours of painting and breathing plant oils, did I notice a change in myself? I felt more present, more connected to the materials with which I was working. I wondered, was that communication somehow reflected in the paintings I made with the plant oils? Were plant essences inspiring me through respiration? That was the possibility I sought to share through the exhibition in the Frick’s greenhouse.

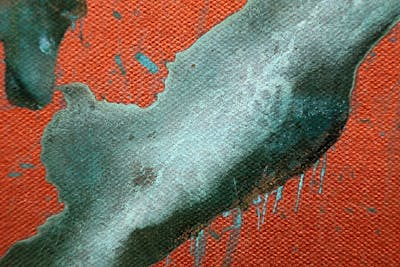

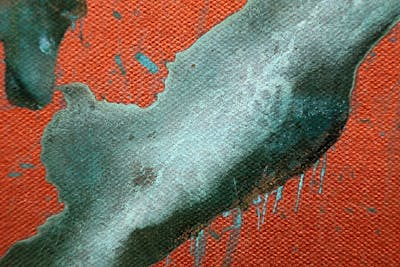

Detail of Oxidation Painting (2017) in greenhouse. Rabbit skin glue, oil paint, urine, salt, vinegar, and copper on canvas, 40 in. x 40 in. Photo by Elise Adibi.

In addition to the paintings I made with essential plant oils, the exhibition included oxidation paintings I made by applying urine to a copper ground. Uric acid in urine oxidizes copper, turning it green. Oxidation painting was invented as a genre in the late 1970s by artist Andy Warhol, who grew up in a neighborhood in Pittsburgh not far from Frick’s greenhouse and even closer to the steel mills he operated with Carnegie. Unlike my paintings in the greenhouse, Warhol’s oxidation paintings were not meant to keep changing after they were finished. To prevent such works from continuing to oxidize, stringent climate controls are required, with surrounding air kept ideally at a constant 70 degrees Fahrenheit and 55% relative humidity. The oxidation process can be slowed by such conditions but not stopped completely. By putting my oxidation paintings in a greenhouse, I allowed them to change at a faster rate.

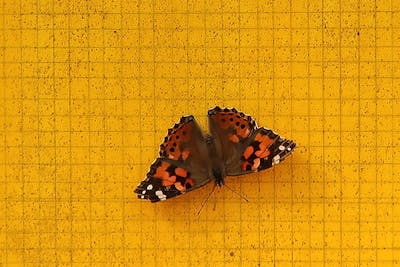

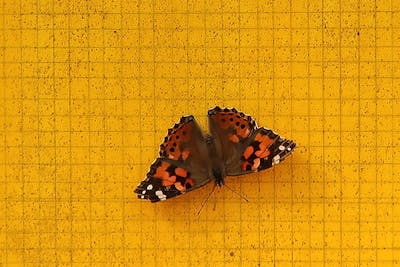

Painted Lady butterfly (Vanessa cardui) on lantana plants in front of Oxidation Spiral (2017). Film still from Elise Adibi, Respiration Paintings (2018).

Thinking about paintings that change led me to Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, published in 1890, seven years before the construction of the Frick greenhouse. Envying the ability of paintings to resist time, Dorian wishes he could switch places with his portrait and remain visibly unchanged while the painting aged. When he first perceives physical changes in the portrait and realizes that his wish has been granted, Dorian wonders more generally if there is some as yet undetermined connection between objects and human feelings. He asks, “Might not all things external to ourselves vibrate in unison, with our moods and passions, atom calling to atom in secret love or strange affinity?” The affinity Dorian experiences between the painting and himself is at once mystical and scientific. In its scientific use, affinity, also known as chemical affinity, describes the force by which atoms are held together in chemical compounds. Happening inside matter, chemical affinity is not something we can see with our naked eyes, yet we might intuit it, as Wilde did in The Picture of Dorian Gray: “Was there some subtle affinity between the chemical atoms that shaped themselves into form and colour on the canvas and the soul that was within him? Could it be that what that soul thought, they realized? – that what it dreamed, they made true?” Subtle affinity suggests that, through prolonged, close attention, vital connections among things may become perceivable. In these slowed-down moments, the aliveness in things can be felt and experienced.

The word “subtle” comes from the Latin subtilis, meaning, literally, “finely woven.” The idea of subtle affinity I am proposing here is like examining woven fabric more closely and perceiving threads not discernable at first glance or from a distance.

Rose Chord (2017). Rabbit skin glue, graphite, oil paint, and essential plant oils of red mandarin, jasmine, starwood, Australian sandalwood, bergamot, sweet orange, rose absolute, rose otto, geranium rose, geranium, aged patchouli, benzoin heart note, and highland lavender on canvas, 30 in. x 30 in. Photo by Elise Adibi.

Looking into the weave of history, perhaps there is a subtle affinity between Dorian Gray and Henry Clay Frick. Frick was 41 when The Picture of Dorian Gray was published. Did he read it? Considering the scandal the book caused, it is likely Frick had at least heard of it. Frick was known for being a ruthless man of business. By 41, he was one of the richest men in the world and was known as the “King of Coke.” In 1889, eight years before the construction of the greenhouse and a year before Dorian Gray was published, a flood in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, killed over 2,200 people. The flood was caused by a break in the South Fork Dam, which contained Lake Conemaugh, a man-made reservoir. On the shores of the lake was the South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club, a private club for rustic getaways by wealthy Pittsburgh industrialists and their families. The club offered recreational escapes into seemingly pristine nature and away from the soot and smoke of the city, pollution caused by the industrial enterprises of many of the club’s own members. As one of the founders of the club, Frick was involved in the purchase of the land and its development. The club’s owners had altered the dam and were apparently aware that it was faulty and might fail, yet they took no action to shore it up. Then the fateful day came. On May 31, 1889, after days of unusually heavy rainfall, the dam broke, flooding Johnstown fourteen miles downstream with a ferocious force. Despite the distance, there was no way to alert and evacuate the city. Many people became trapped in the debris that piled up against the Stone Bridge, which still stands today. That wreckage then caught fire, so those who didn’t drown burned. It was one of the worst disasters in the United States up to that time. Despite evidence that the South Fork Club members had been warned and knew that the dam was vulnerable, a court ruled that the flood was an “Act of God,” and they were never held legally or financially accountable. It is now possible to look back on this event as a harbinger of things to come with global warming and the increased severity of natural disasters exacerbated by human activity. Though there was never a public admission of guilt by the club members, a private confession of sorts was perhaps made indirectly by Frick. On his deathbed, Carnegie asked to speak with Frick, and the latter responded with a note that read, “Tell him I will see him in hell, where we are both going.”

Painted Lady butterfly (Vanessa cardui) in front of Lemon Grid (2017). Rabbit skin glue, graphite, oil paint, and essential plant oils of lemon, bergamot, and yellow mandarin on canvas, 30 in. x 30 in. Photo by Elise Adibi.

The relationship between Carnegie and Frick had soured years before. In order to force Frick out of his company, Carnegie had given him a massive settlement. With this payment, Frick moved to New York City in 1905, and he spent the remainder of his life collecting art. One of the prizes of Frick’s collection is St. Francis of the Desert (1476−1478) by Giovanni Bellini. Painted 35 years after Jan van Eyck’s death, it is a remarkably well-preserved early work in oil on panel. St. Francis is known as the patron saint of animals and the natural environment. He was said to be able to communicate with other species, calling other creatures his brothers and sisters. Once, when he was walking in the wild, he came upon birds in a tree. He stopped to preach to them, and they flocked around to listen. In Bellini’s painting, St. Francis is seen facing the sun with his arms open. Perhaps he is receiving inspiration for his song Canticle of the Sun, also known as Praise of the Creatures. In the upper left-hand corner of the painting, a laurel tree also seems to be communicating with the sun, leaning back in a way that echoes the posture of St. Francis, with some of its branches raised towards the light. Is it possible that living with this painting in his New York mansion made Frick more sensitive to the natural world and provided him with some healing? Perhaps the spirit of St. Francis could be felt in the greenhouse where my paintings were installed. Along with humans, non-human visitors came and experienced the works, including bees and butterflies, praying mantises, moths, spiders, occasional birds that flew in, even the neighborhood cat. Insects were the most frequent visitors, and they became a part of both the experience of the paintings and the paintings’ experience, flying around them, landing on them, and — strangely — sometimes even dying in front of them.

Dead moth in front of Oxidation Spiral (2017). Rabbit skin glue, oil paint, urine, salt, vinegar, and copper on canvas, 30 in. x 30 in. Photo by Elise Adibi.

Rain drops on Yellow and Pink Pour Painting (2017). Photo by Elise Adibi.

The summer of 2017 was particularly wet in Pittsburgh. There were frequent, torrential rain storms, and those “rainfall events,” associated with climate change, soaked the greenhouse and muddied the plant beds surrounding the paintings. Despite the Frick museum’s best efforts, the paintings got dripped on from above and splashed from below. Contact with water accelerated their rates of change. Moisture saturated the canvases, quickening their organic potentials and making them perfect hosts for microorganisms. Over their six-month stay in the greenhouse, the paintings revealed images different from those I had initiated, developing in ways independent of my gestures and intentions. For example, raw canvas darkened as mold infiltrated its weave, and paint brightened in contrast. The paint seemed to emanate from the surfaces, glowing brightly, as if lit from within or incandescent. Mold grew in organic patterns over straight lines I had drawn.

Rose Monochrome (2017). Rabbit skin glue, graphite, oil paint, and essential plant oils of rose, bergamot, sweet orange, and lemon on canvas, 30 in. x 30 in. Film still from Elise Adibi, Respiration Paintings (2018).

Mold and mildew on Rose Monochrome (2017). Photo by Elise Adibi.

Surfaces represented transformations underway. It was not easy for me to watch the process of the paintings changing and decaying. The mold was literally eating them. In my studio, I had spent many months making them, realizing their forms. They were finished, but then they were food. When I first saw mold on the paintings, it was physically painful. It took time for me to adjust to their emergent aspects. Once I could let go of my idea of the paintings as fixed objects, I could relate to them differently and consider our shared agency. I saw a new beauty in them. Some of the plants seemed to grow towards the paintings.

Bee on cone flower next to Yellow and Pink Pour Painting 2 (2017). Rabbit skin glue, graphite, oil paint, and essential oils of lemon, Peru balsam, red mandarin, ylang ylang, bay laurel, and palo santo on canvas, 30 in. x 30 in. Film still from Elise Adibi, Respiration Paintings (2018).

One of the lantana plants grew so close to one of the oxidation paintings that copper oxide fell on its leaves, dusting it with bright turquoise pigment.

Oxidation dust on lantana plant in front of Oxidation Spiral (2017). Photo by Elise Adibi.

Other plants — such as lavender, French marigolds, coneflowers and black-eyed Susans — grew over parts of the paintings. The colors of their petals related in interesting ways to the colors in the paintings, sometimes even matching them perfectly.

Cone Flower and Yellow and Pink Pour Painting 2 (2017). Photo by Elise Adibi.

The paintings and the plants were becoming one condition. I could surrender the paintings to this process.

In late summer, the show was at the height of its vitality. The plants were in full bloom, and the paintings were, too. They had blossomed and borne fruit, manifesting their resilience. In early autumn, the greenhouse was graced by visits from bumble bees and painted lady butterflies. The butterflies landed on the paintings, drawn to them by their colors or their smells — or perhaps both. The presence of these pollinators was a hopeful sign.

Painted Lady butterfly (Vanessa cardui) on Lemon Grid (2017). Photo by Elise Adibi.

Review

By David L. Hays

As a type of relationship based on “natural” interest or resemblance, affinity is usually framed in terms of subjective attraction or structural similarity, but its scientific definition — “the degree to which a substance tends to combine with another” — resonates in more interesting ways with contemporary thinking about nature and culture. Modern thought long supposed that humans are “critically” distant from the purely material realm, construing the latter as “nature,” “environment,” or (not so) simply “space.” However, new thinking about ecology and subjectivity have challenged that premise, blurring traditional distinctions between human and non-human agents and conditions. Predicated on combination, affinity contributes to that blurring by eroding the limits on which modern taxonomies depend, destabilizing inherited systems of classification. At issue is the basic structure of relationship, in the modern version of which things1 remain separate even as they are connected, as through attraction or similarity. To be relatable in the modern way, things must be in one sense the same and in another sense different. That paradox is most evident in opposites, which are extremes of a single condition, like the end points of a single line. But in relationships based on combination, difference is distributed, and the outcomes of that synthesis are both singular and substantial.

Elise Adibi’s essay “Subtle Affinity” is an exploration of distributed difference with singular and substantial results. The text opens with a practical account of Adibi’s exhibition “Respiration Paintings,” held in a historic greenhouse at the Frick Pittsburgh, and it closes with personal reflections on the conditions and significance of that event. In between, one thing leads to another as Adibi addresses a sequence of topics, including the coal-based industry of Henry Clay Frick, greenhouse architecture, the greenhouse effect, essential plant oils, plant communication, oxidation painting, Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), a tragic flood in 1889, and Giovanni Bellini’s painting St. Francis in the Desert (aka St. Francis in Ecstasy) (ca. 1476 – 78). At an obvious level, those subjects are related through structural similarities — for example, between greenhouse architecture and greenhouse effect, or between oxidation painting and The Picture of Dorian Gray. But at a less obvious level, ideas combine in subtle yet evocative ways — for example, the experimental attitude of Jan van Eyck and people ingesting flaxseed oil today, or the tragic flood in 1889 and Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert — introducing moments of exceptional interest that propel the text forward.

Given her work as a painter, Adibi is understandably intrigued by chemical affinity (“the force by which atoms are held together in chemical compounds”) and its potential to link human and non-human agents, but her sense of affinity is also more abstract and generative. For example, reflecting on Oscar Wilde’s account of subtle affinity in The Pictures of Dorian Gray, Adibi wonders if such a relationship might exist between Dorian Gray and Henry Clay Frick. What makes that question interesting is the potential not for structural similarities between two life narratives, nor for subjective attraction between Frick and Wilde/Gray, but rather for Frick and Gray — through some portion of their vast yet specific meanings — to combine spontaneously, producing something new.

In her extended meditation, Adibi also wonders, “Is it possible that living with [Bellini’s St. Francis] in his New York mansion made Frick more sensitive to the natural world and provided him with some healing?” Here, Adibi is not suggesting that Frick looked at the image over time and was converted through reflection on its formal content or related narrative.2 Instead, she is invoking other forms of affinity — possibly chemical, but certainly more subtle — through which Frick and St. Francis might combine, producing a new condition. Having laid out that possibility, Adibi adds, “Perhaps the spirit of St. Francis could be felt in the greenhouse where my paintings were installed.” Given legends about that saint’s ability to communicate with animals and the sense that he both loved and was loved by them, “the spirit of St. Francis” is ready shorthand for affinity in its various forms, particularly in the context of human/non-human relationships.3 But it is also shorthand for letting go of expectations, accepting4 other agencies and unforeseen possibilities — and, in Adibi’s case, seeing “a new beauty” in her own paintings as transformed by moisture, mold, and oxidation.

Looking to art for both cultural information and personal insight is a deep-seated tradition — not to mention a basis of art history. Similarly, looking to natural phenomena for both empirical information and evaluative signs, such as affirmations5 and omens, is an ancient and ongoing practice. But looking to paintings to see how they are “becoming one condition” with plants (and fungi), as Adibi does, is less familiar and less sure, not least because recent scientific research and work by artists and writers is rapidly transforming human understanding of the natural world — showing, for example, that plants have the ability to “hear,” “remember,” and “articulate” based on individual experiences.6 In this new context, the shared agency of paintings and plants (and fungi) — which a modern view would construe as purely mechanical — becomes unexpectedly intimate: “One of the lantana plants grew so close to one of the oxidation paintings that copper oxide fell on its leaves, dusting it with bright turquoise pigment.” Difference is distributed, and the result blurs the traditional boundary between art and nature, presenting them instead as conditions in which human and non-human agencies combine, producing something new.

Notes

1

“Things” refers here very broadly to objects, actions, conditions, and ideas — including the thoughts, moods, and memories mentioned by Adibi.

2

In 1912, when the London-based art dealer Colnaghi was seeking to sell Bellini’s St. Francis, its agents did not at first show the painting to Frick, understanding that he did not like religious works and believing that “he would not understand [it] or be interested.” (Susan Rutherglen and Charlotte Hale, In a New Light: Giovanni Bellini’s “St. Francis in the Desert” (New York, NY: The Frick Collection in association with D. Giles Ltd., London, 2014), 78, quoting a letter from Otto Gutekunst of Colnaghi to Charles Carstairs of Knoedler.)

3

In 1979, Pope John Paul II proclaimed St. Francis the “Patron of Ecology” and “heavenly Patron of those who promote ecology.” See Pope John Paul II, “S. Franciscus Assisiensis caelestis Patronus oecologiae cultorum eligitur,” in Acta Apostolicae Sedis: Commentarium Officiale LXXI, 1509 – 1510. (http://www.vatican.va/archive/aas/documents/AAS-71 – 1979-ocr.pdf)

4

“To accept” means not to receive but to consent to receive. Its Latin root, accipere, means “to take something to oneself.”

5

For example, humans feel affirmed when animals give them positive attention and when plants and animals thrive under their care.

6

See, for example, Lindsey french, “land of words: a collection of poetry by plants,” Forty-Five: A Journal of Outside Research (November 16, 2018)

Biographies

Elise Adibi is a painter whose practice has come to include installations, horticulture, filmmaking, architecture, aromatherapy, and writing. She received an MFA from Columbia University, an MArch from the University of Pennsylvania, and a BA in Philosophy from Swarthmore College. Adibi has received fellowships and awards from the Terra Foundation for American Art, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, the Heinz Endowments, and the Pittsburgh Foundation. Her work has been presented in solo exhibitions at Full Haus (Los Angeles, CA), Louis B. James (New York, NY), The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study (Cambridge, MA), Churner and Churner (New York, NY), Southfirst (Brooklyn, NY), Allegheny College (Meadville, PA), and the Frick Pittsburgh, as well as in numerous group shows, with reviews in Artforum, The Boston Globe, The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and Blouin Modern Painters, among other publications. Email: eliseadibi@gmail.com

David L. Hays is co-editor of Forty-Five, co-director of the gallery Space p11, founding principal of Analog Media Lab, and Associate Head of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Trained in architecture and history of art, his scholarly research explores contemporary landscape theory and practice, the history of garden and landscape design in early modern Europe, interfaces between architecture and landscape, and pedagogies of history and design. Hays is the editor of Landscape within Architecture (2004) and (Non-)Essential Knowledge for (New) Architecture (2013), both by 306090/Princeton Architectural Press. His essays have appeared in a wide range of journals — including Harvard Design Magazine, Eighteenth-Century Studies, Polysèmes, The Senses and Society (Oxford), Matéricos Perifericos (Rosario, Argentina), Tekton (Mumbai), and Landscape Architecture China (Beijing) — and as chapters in numerous books. As a designer, Hays’s work explores the production of environmentally responsive objects using low-cost, low-tech materials. With particular interests in dynamic systems, environmental phenomena, and craft, his process crosses lateral thinking and intuition with grounded experiment. Email: dlhays@forty-five.com