The next time you hear someone talking about algorithms, replace the term with “God” and ask yourself if the meaning changes. Our supposedly algorithmic culture is not a material phenomenon so much as a devotional one, a supplication made to the computers people have allowed to replace gods in their minds, even as they simultaneously claim that science has made us impervious to religion.1

Algoritmos, the Spanish word for algorithms, was the title of one of my mathematics books in middle school. I remember being fascinated by this term whose meaning or power I did not fully grasp: a magic word or spell with which to open a universe of possibility. Twenty years later, in an unexpected twist, the mysteries behind it became the focus of my interest in architecture and design.

According to Google Books Ngram Viewer, use of the word “algorithm” peaked first in 1991 and again in 1996 (around the same year I was using the math book). Then, after a brief decline, its use began to grow, and it has been doing so at a fast pace since 2006. No day goes by when we do not hear about the impacts of algorithms on our lives — most evidently, through our interactions with online platforms, such as Google and Facebook. We live in a time of seemingly limitless trust in these mathematical processes. We allow them to control vast areas of our existence, accepting their outcomes as if absolute truths. We treat algorithms as objective tools, with blind faith in their mathematical certainty — a form of belief subconsciously ingrained in human minds since the Enlightenment through the ideal of a mathesis universalis. However, the process that determines so much information — from recommendations on Netlflix and Amazon, to ideal commuter routes, to our suitability for jobs or relationships — is anything but objective.

Even though the Greeks already warned us about the perils of assuming technological knowledge as superior, technology is still framed as fair and faithful in service to human beings, the right approach to any problem we seek to resolve. However, as Ed Finn has stated, “aside from the most simplistic cases, we will never know how algorithms know what they know.”2 Therefore, trusting them with running our world seems neither rational nor wise. Yet, what Finn calls the computational space of imagination arises in that very universe of the unknown, a place where we can challenge and reinvent our relationship with technology. Instead of looking for the most optimized results, embracing the space of the unknown allows us to see algorithms not as tools that automate design processes, both affirming and limiting our agency, but rather as collaborative others in the context of creative development. A human-machine feedback loop that sparks imagination and not just the standardization most architectural software allows.

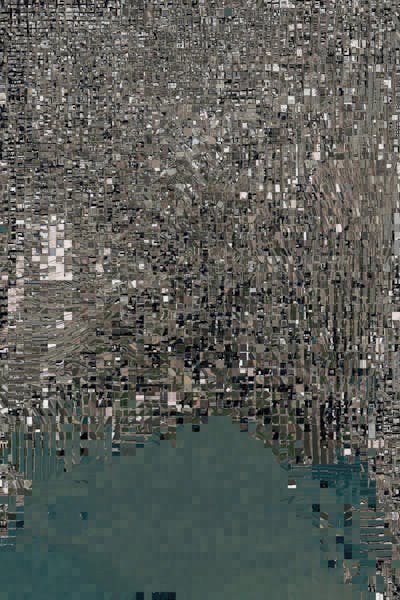

Stochastic Cities explores that computational space of imagination by rearranging an aerial image of Chicago using a combination of computer vision and machine-learning algorithms, not with the intention of finding an ideal configuration but as an experiment to query unexpected associations. The original orthoimage represents the city from Division Street in the north to 28th Street in the south, and from Racine Avenue in the west to the end of Navy Pier in the east. It was cut in 3,750 squares following the orthogonal grid so characteristic of Chicago. Each piece was then processed by a classifier, a neural network trained in this case on the ImageNet dataset, one of the first large-scale image databases available online, that learned to identify to which category each new observation belonged. This classifier “extracted” the multiple features of each square, variables representing the relations between pixels, that were interpreted and grouped by a t‑SNE (t‑Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) algorithm. These associations were then projected back onto the original grid.

A t‑SNE algorithm is a technique for dimensionality reduction, which is very useful in the visualization of high-dimensional datasets. It consists on reducing the number of random variables that are under consideration — in this case the ones provided by the classifier — by allowing the algorithm to find patterns in the data, bringing to the foreground the principal connections present. As its name indicates, the process is stochastic — meaning, one of its functions is initialized randomly. As a result, each run could output a unique visualization.3 In Stochastic Cities, the process was run four times. Although the overall compositions of the resulting images were distinct, the associations between and among the components followed a consistent logic, maybe similar to the one we would obtain if we asked a human who had never seen a city from above to organize those 3,750 images.

The four runs generated similar effects, such as a visible shift in scale, perhaps because the parks were not joined as one, like the water, but rather were scattered along the shore, as hybrid links between natural and built environments. The new images of Chicago appear to be organized by typology, presented as a limitless city that has lost its center. A generic city at first sight, a mix of predictability and arbitrariness in the treatment of metropolitan systems fosters uncanny situations, such as the way piers enter the water in an accentuated embrace, or the consistent reconstruction of McCormick Place as a vortex of turning roads, not to mention the impossible connections of diagonals and curves that generate magical in-betweens paired with seamless juxtapositions of buildings that totally erase the mosaic quality of the grid in the sections they occupy.

What does the algorithm know? Not that McCormick Place is the largest convention center in North America, nor that the Chicago River had its flow reversed. It knows only what it has been taught, and that mix of specificity and alternate logic nurtures an unexpected urbanism. Back and forth, through these operations, the margin becomes blurry between what the computer “sees” and what our eyes read in the outputs. This reflexivity is present in the real dynamics of urbanism as well as in the space of computational imagination, where the relationship between humans and machines becomes that of collaborators in a speculative, generative venture.

Looking again at the new images of Chicago, I discovered a choice the algorithm had made, one I had not noticed before and that surprised me. A little square of water, isolated between roads and away from similar units, suffered that same fate in each of the four iterations: a lonely pond that, given the magical rationality of the images, my mind could not explain. I will surely never know why the algorithm chose to place that unit in that way, but I embrace that. In remaining beyond the scope of my understanding, the mysteries of the algorithm make evident the collaborative nature of our shared work.