1. This is the history of a woman and her glass house. It is as true an account as I can devise.

2. Better known for the glass house that bears her name and the rumor that she was the jilted lover of Mies van der Rohe, Dr. Edith B. Farnsworth was also a poet and a translator of poetry.

3. Her last work was published in 1976, a year before her death. A final proof of this book-length English translation of works by Italian poet Albino Pierro is held in her archive at the Newberry Library. Farnsworth’s strikes and edits of the text are evident in blue pen, her stuttering lines in each poem an indication of her advanced age and declining health. On the cover page the title, OCCHIELLO, is crossed through and in all capital letters NU BELLE FATTE is written — a last minute edit perhaps directed by Farnsworth, but written in a younger and stronger hand. For reasons lost in history, the title of this collection was changed from occhiello—the Italian word for eyelet, a small hole or perforation — to nu belle fatte, Lucanian dialect for the Italian una bella storia, a beautiful story.

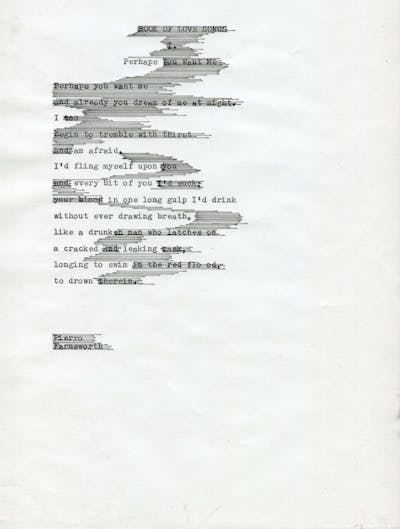

4. The collection opens with this poem:

Perhaps you want me

and already you dream of me at night.

I too

begin to tremble with thirst

and I am afraid

I’d fling myself upon you

and every bit of you I’d suck;

your blood in one long gulp I’d drink

without ever drawing breath,

like a drunken man who latches on

a cracked and leaking cask,

longing to swim in the red flood,

to drown therein.

5. How does one make a history from this?

6. The history of the Farnsworth House, as told by historians, ignores these poems, but reads like the plot of a novel. A powerful woman — a single, wealthy Chicago-area physician — meets an internationally renowned modern architect at a dinner party, a man who has left his wife and daughters to immigrate to McCarthy-era America from his native Germany. By the time dessert is served, she has hired him to design a weekend house in rural Illinois.

7. Some of this history is drawn from her unpublished memoirs. I fill out all of the necessary forms to make an appointment with each document.

You write about your life only if you are willing to show yourself while doing the living, she wrote.

set down syllable by syllable

whispers as real

as a hundred shouts

radical, traumatic, highly organized.

8. The story follows that during the three-year design process, Mies and Farnsworth socialized frequently in Chicago with mutual friends and acquaintances. On weekends, they made trips to the country to survey the idyllic strip of land she had purchased in the floodplain of the Fox River just outside of Plano, Illinois, picnicking with his employees and students, mutual friends, architects visiting from other countries. She became enamored of the architect — indeed, the two are rumored by many sources to have been lovers, although there is no evidence of this in her memoirs.

9. I myself have held photographs that show them sitting together on a picnic blanket, surrounded by friends. Without a suit jacket, the architect’s waistline is expansive. Sitting on the ground in a skirt, her knees are scalpel sharp.

10. “It shouldn’t be this way, but I’m afraid that this story is going to end badly,” a friend warns her. I mark up a Xerox form and paperclip this letter to it to remind myself of this fact.

11. The house that he promises to build her is elegant and entirely transparent and held above the ground on thin steel columns. It is unlike any other. House Beautiful labels it a threat to democracy. She simply complains that she has nowhere to store her belongings. He tells her this is because it is ‘beinahe nichts,’ almost nothing.

12. A little known fact of their relationship is that while he was her architect, she was his physician. Stop reading for a moment. Imagine being the physician of a man who fears death.

13. “I want to know what I have to expect after death,” he once demanded of her. “A man will always want to know about his hopes for immortality. He won’t want to know that his fate is the same as the snowflakes on the window, the salt crystals on the dinner table.”

What story do you want? I ask out loud in the silence of the reading room.

14. Life progresses, inevitably, toward an end. And yet, it has supernatural moments. One spring afternoon in 1950, they are joined by a British architect on a visit to the house during construction.

The trees and meadows, as we saw them from our stone shelf, faded into a vision and in the sky there floated a blush-pink celestial body like a pale pink moon, supremely large. We stared at one another and at the big pink heavenly body and at our altered world. “You don’t imagine that we might have slipped out of orbit, do you, after so many years in the same one?” suggested Mr. Dark, now quite subdued. The two horizontal planes of the unfinished building floating over the meadow were uncannily beautiful.

15. She records this event in a matter-of-fact tone in her memoir: an unknown planet hovers so close to them that they begin to question the orbital alignment of Earth’s trajectory. They find themselves in a glass house at the beginning of what seems to be an unraveling of the order of all things in the universe. A chain of events perhaps put in place by an unusual house.

16. Once the phenomenon is traced back to wildfires in Canada (an explanation that, in truth, I do not fully understand), she returns to her complaints about the house emerging from the ground. There is already the local rumor that it is a tuberculosis sanitarium.

17. Things fall apart in the usual way. They simply slip out of orbit.

18. She believes the architect is cheating her on the price of the house. She receives phone calls from the interns letting her know that the furniture she never requested, furniture of the architect’s design, is going to be delivered. She refuses to accept it. She sends a letter to the architect’s office stating that no further expenses are to be approved on the construction of the house.

19. Perhaps, as a man, he is not the clairvoyant primitive that I thought he was, but simply colder and more cruel an individual than anybody I have ever known. Perhaps it was never a friend and a collaborator, so to speak, that he wanted, but a dupe and a victim. These are her last words on the subject.

20. Historically, the cause of their rupture will be recorded as heartbreak. So to speak.

21. Historically, she will be recorded as ugly. “Edith was no beauty.” But she was brilliant, they will admit. Indeed, she had cultivated her mental powers in order to compensate for this unfortunate appearance. (It is said.)

22. History, of course, is the process of constructing and interpreting.

23. Her first evening in the glass house unfolded like the still echo of a temple. She had just one light bulb to drown out the moon. The phone rang: “Are you down there alone in those cold meadows?” It was an uneasy night, she writes, with little explanation.

24. When I write this history, why do I want to dismiss the possibility that these two fucked?

25. When I read this history, why does everyone else entertain the possibility that they did?

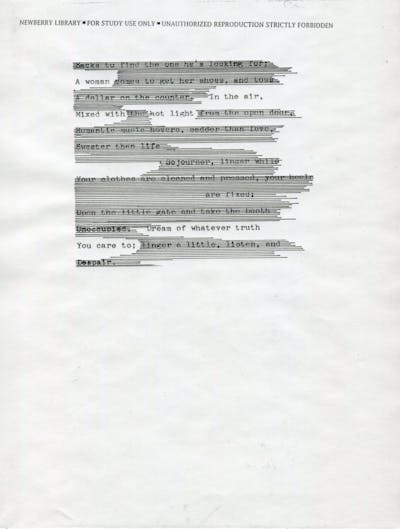

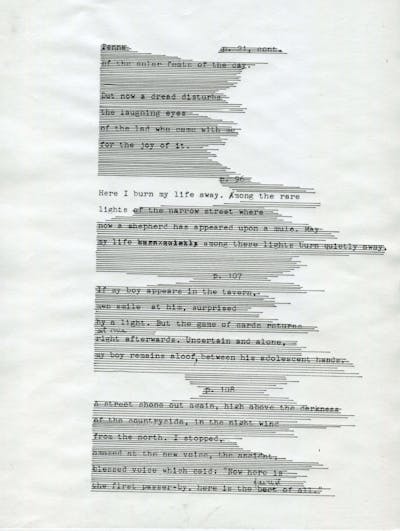

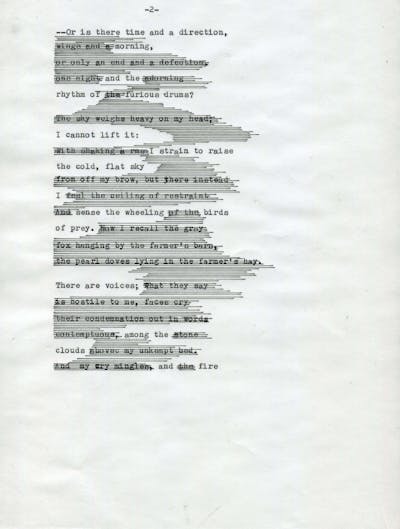

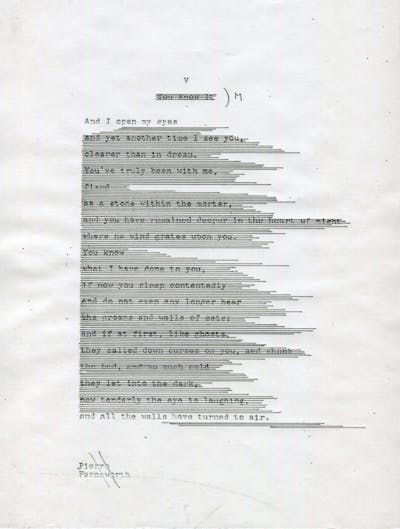

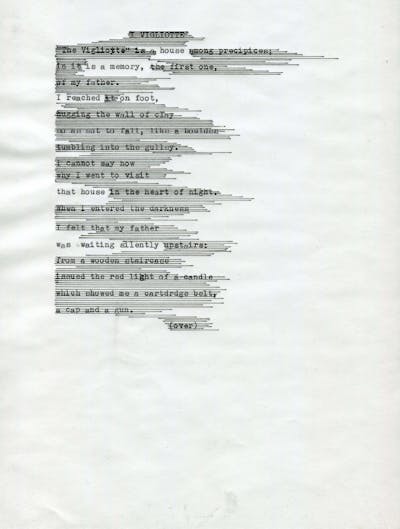

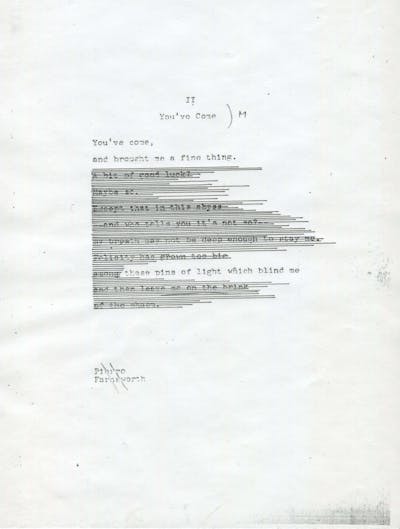

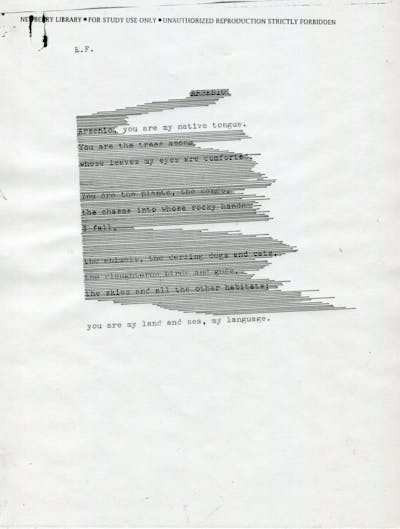

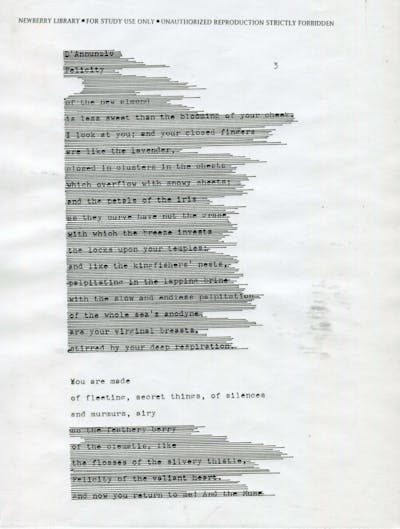

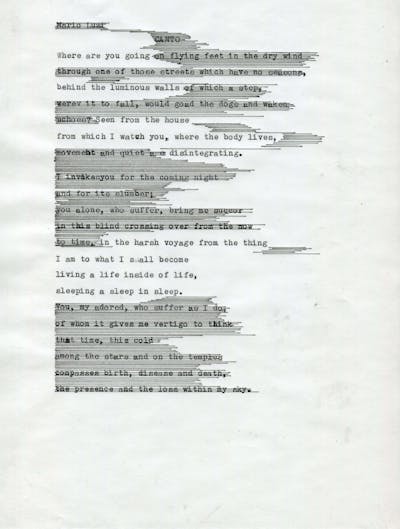

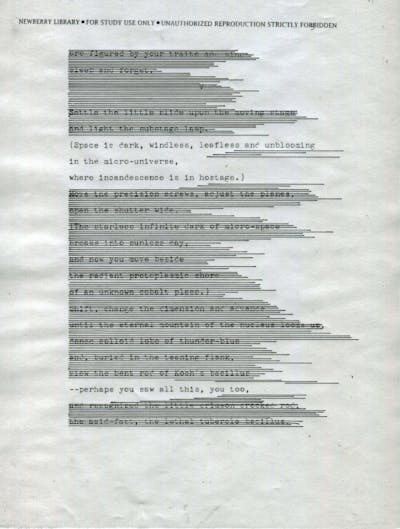

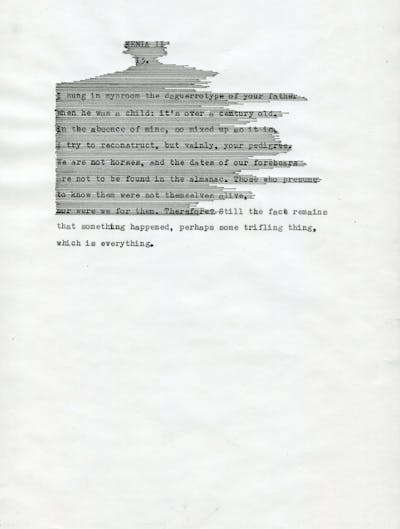

26. I wonder if, privately, she continued to dwell on the supernatural. Not in her memoirs — in which she records her complaints about the house and the architect with needling precision, and the details of the rather boring trial in which they sued each other — but in her poetry. There are volumes and volumes of it, most of it labeled “Unidentified” in her archive, though her initials appear at the top corner of nearly every typescript. In these poems, most of them never published, she writes about space.

27. What is more supernatural than space?

Settle the little slide upon the moving stage

and light the substage lamp.

(Space is dark, windless, leafless and unblooming

in the micro-universe,

where incandescence is in hostage.)

Move the precision screws, adjust the planes,

open the shutter wide.

(The starless infinite dark of micro-space

breaks into sunless day,

and now you move beside

the radiant protoplasmic shore

of an unknown cobalt place).

28. –perhaps you saw all this, you too, she concludes.

29. When poets address you, they are (usually) addressing some amalgamation of former loves. It is unknown to whom Dr. Farnsworth refers. It could be the architect. She also kept black poodles, and was close with a man named Hugo. There was a Katherine in her 20s and a brother disowned by the family. There are many lost yous in a life. To move forward we must choose to suspend knowing the meaning of you.

30. She further confuses us by writing that, sometimes, you may become I.

31. Space is a strange word, preceded chronologically in architectural discourse by volume and void. Space is a property of the mind, Adrian Forty warns anyone who is trying to undress its ambiguities. To untangle its meaning would be to untangle some part of ourselves, some navel long since healed over. It is the apparatus through which we perceive the world.

32. Blame it on the German language. Space, raum, is material enclosure, room, and philosophical concept. By matter of fact, and without much work, Peter Collins tells us, a German speaking person understands room as a small portion of limitless space.

33. Farnsworth sought to put limbs to this limitlessness, this slipping of room into space, out of orbit.

I looked about me

it seemed to me that a long hand

would stretch out from the ceiling

and draw me up into the dark

like a feather snatched by the wind.

By morning

I had forgotten everything.

34. What if their dispute wasn’t sexual, but philosophical? That she kept putting limbs on his vision of the infinite — in a world of eternal life beyond salt crystals, beyond snowflakes, she was shaking her nightgown at him, asking for a drawer in which to hide it.

35. What do you do with an architect who fears death and draws floor plans from close readings of Thomas Aquinas?

36. Men who are religious — about god, or space, or the infinite or some unholy hybrid of the three (which are maybe simply one thing) — are also deeply conflicted. Everyday, they spill beyond the perimeters of their own bodies. We all do.

37. Try to hold space in your cupped hands. Close them and hold them up to the light. Peer into the navel that your thumbs have locked together to form. There, in the flesh colored light you can see space seeping out. It’s alright. We can’t talk about the infinite without dragging our bodies into it. And yet, it’s a place (?) where bodies do not belong.

38. The infinite is a being without constraint. The architect did not talk to the doctor about God directly. Instead, he would simply pose this question: “Why tie one’s hands voluntarily?”

39. “Who still feels anything of a wall, an opening?” Much is contained in a question.

40. I wonder if they weren’t just looking for two different scales of the infinite — his expanding ever outward through a glass wall, toward the edge of the horizon and the limits of human perception, hers expanding ever inward through the glass lens of a microscope.

41. Constructing some relationship between the two of them is difficult. They were intimates, and as intimates the space between them was short, a shallow chasm and like all shallow chasms it contains a dearth of communication. If only thousands of miles had separated them, perhaps they’d have narrated it for us.

42. Or perhaps not.

43. And so we are given infinite possibilities.

44. We must make meaning out of things. (Thomas Aquinas, 13th century)

45. An absence of narrative is an absence of meaning. (Roland Barthes, 20th century)

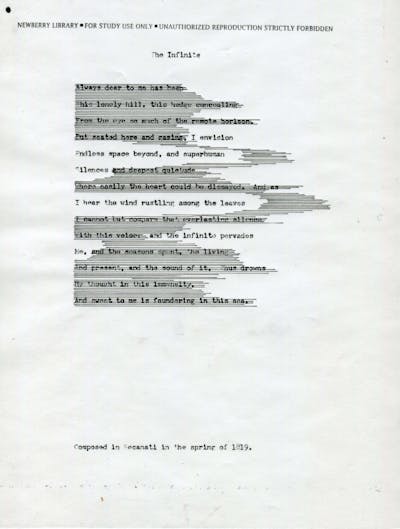

46. Some days, the infinite sounded good. She could envision endless space beyond, and superhuman silences. She could hear the wind rustling among the leaves. The infinite pervades me, she wrote in some feverish moment that you don’t read about in any books.

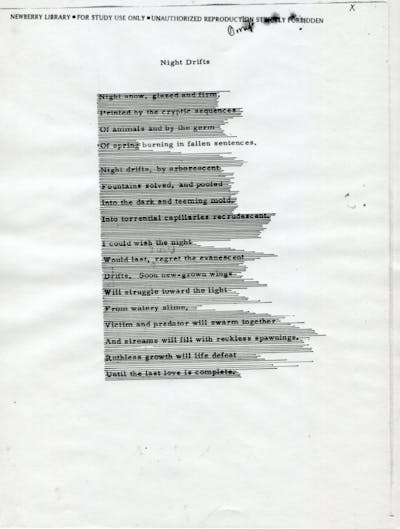

47. And yet, night drifts. Burning in fallen sentences.

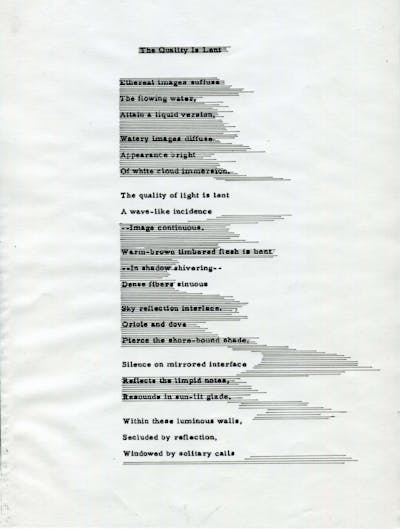

48. And daylight is wave-like, shivering and sinuous on luminous glass walls.

49. And my reflection in the glass is poor company.

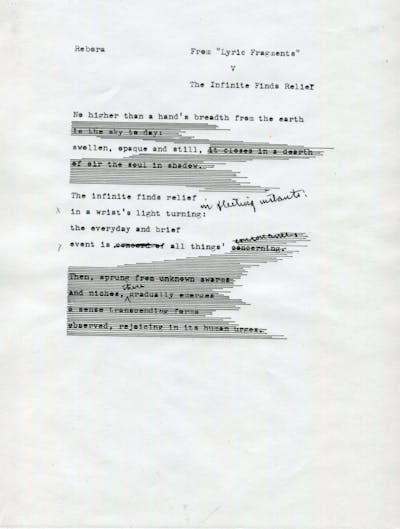

50. The infinite finds relief, she writes, in a wrist’s light turning: the everyday and brief event is all things.

51. For every measure of the infinite that we can see, there is more buried behind it. A computer programmer appears on my laptop screen and suggests that the Internet you can view is like the tip of an iceberg visible above the surface of the ocean. Beneath that is most of the mass of that glacial body — the deep Internet — to which few have access.

52. When she says this I am reminded of the vanishing point in Renaissance paintings that would be concealed, often, by a painted panel and a golden lock, because to look at the vanishing point — even the humanly constructed one — would be to try to look God squarely in the eye.

53. Wikipedia is less shy about it and offers a few helpful mind exercises to imagine the infinite—how deep is the sky?

54. This, of course, is just the tip of the iceberg.

55. To the doctor, the man we see is only the man who is visible.

56. Visibility,

that exceedingly small segment of the spectrum

which lies between the ultra-violet and the infra-red.

The rest of his being, she writes, recedes infinitely into the shorter

rays of

his deep

his unconscious

his past life

his predecessors

longer and longer waves of seed.

57. Perhaps there is an age at which one becomes invisible to men. Perhaps she crossed this horizon while they were working on the house. I experiment with invisibility myself by walking around my neighborhood in sweatpants on Thursdays. I do not mind receding in this way. I return to myself.

58. Even an invisible woman is visible behind glass. To a glass house, the world is endowed with eyes.

Did the river see the house

the house where this body lives?

Who better than you knows

what I want?

The few small words which I address to you

seek to be new, but they are ancient.

59. Aligning these poems with the history of the house, with the possibility of some relationship between the client and the architect, is difficult to do. Poems have little incentive to be straightforward.

60. Plato believed that poetry was dangerous because it was too easy to compose without knowledge of the truth.

61. But “the true corrupting power of poetry resides in its charm,” Susan Stewart writes, “and the most dangerous aspect of charm is that it is unthought” — just a bright instinct within us.

62. It is unknown whether Dr. Farnsworth wrote her poems during her dialogs with the architect, or after it all broke off. It is unknown whether allusions to “you” are an indication of the architect, or not, or other lovers, or not. The connection of these words to the history of the house is tenuous, though not entirely absent. It simply recedes.

63. Receding behind history is poetry. First we were mute, then we stammered sound and song. This is long before we could thread together a story.

64. In her working files of the translation of Pierro’s poems, Farnsworth makes a change to “Perhaps You Want Me.” Above the title of the poem was typed “Love Songs,” through which she makes two strikes.

65. These are not love songs, there is no eyelet or opening to truth, this is simply a story.

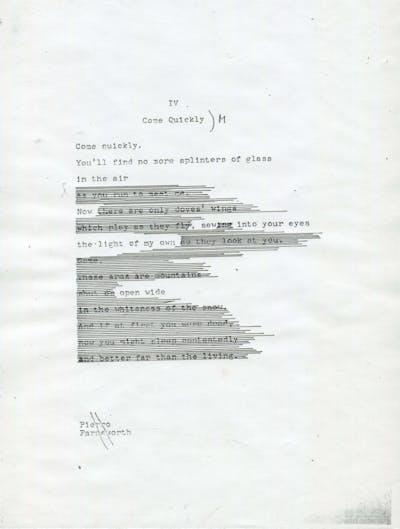

66. The fourth poem in her translation of Pierro, OCCHIELLO NU BELLA FATTE, opens:

Come quickly.

You’ll find no splinters of glass

in the air

as you run to meet me.

67. Any love affair is a narratological construction.

68. And writing architectural history is an inexact art, a problem of evidence.

69. We could make meaning out of one of the few handwritten poems in Farnsworth’s archive, this one dated two months after Mies’ death. It is evidently a love poem.

It opens with

— — - you are my native tongue.

You are the trees among

whose leaves my eyes first opened are comforted.

It closes with

You are my land and sea, my language.

70. “What wish is enacted, what desire is gratified,” asks Hayden White, “by the fantasy that real events are properly represented when they can be shown to display the formal coherence of a story?”

71. Desire for fullness, continuity, causal connections.

72. If anything resists the narrative cloy of love and of history, it is poetry. Poetry is made as much of language as of the absence of language. Poetry contains space: the gaps and pauses that the narrative structure of history cannot accommodate.

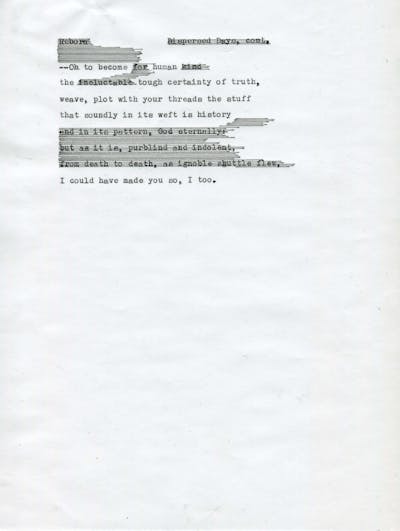

73. The following words can be lifted out of one of the last unpublished poems that she translated:

Weave, plot with your threads the stuff

that soundly in its weft is history

I could have made you so, I too.

ATTRIBUTIONS

Sentence #4: Albino Pierro, “Perhaps you want me,” in Nu Belle Fatte. Una Bella Storia. A Beautiful Story, trans. Edith Farnsworth (Milano: All’Insgna del Pesce d’Oro, 1976), 43.

Sentences #7, 10, 13, 14, 16, 19, 23: Edith Farnsworth, “Memoirs,” unpublished ms. in three notebooks, Farnsworth Collection, Newberry Library, Chicago, unpag.

Sentence #21: Franz Schulze, Mies van der Rohe: A Critical Biography (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1985), 258.

Sentences #27, 28: Edith Farnsworth, “Arsenio,” 1969, unpublished poem, Farnsworth Collection, Newberry Library, Chicago. Excerpts.

Sentences #31, 32: References are made to the chapter “Space” in Adrian Forty, Words and Buildings (New York: Thames & Hudson, Inc., 2000), 256 – 275.

Sentence #33: Albino Pierro, “U Mamone,” trans. Edith Farnsworth, unpublished, no date. Farnsworth Collection, Newberry Library, Chicago, unpag. Excerpt.

Sentence #38: Attributed to Mies van der Rohe.

Sentence #39: From the notebook of Mies, page 61, 62 (collection of loose pages preserved at the Mies van der Rohe Archive of the Museum of Modern Art in New York), 1927 – 1928. Excerpt appears in Fritz Neumeyer, The Artless Word, trans. Mark Jarzombek (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1991), 289.

Sentence #46: Giacomo Leopardi, “The Infinite,” 1819, trans. Edith Farnsworth, unpublished, no date. Farnsworth Collection, Newberry Library, Chicago, unpag. Excerpt.

Sentence #47: Edith Farnsworth, “Night Drifts,” unpublished, no date. Farnsworth Collection, Newberry Library, Chicago, unpag. Excerpt.

Sentence #48: Edith Farnsworth, “The Quality is Lent,” unpublished, no date. Farnsworth Collection, Newberry Library, Chicago, unpag. Excerpt.

Sentence #50: Clemente Rebora, “The Infinite Finds Relief,” trans. Edith Farnsworth, unpublished, no date. Farnsworth Collection, Newberry Library, Chicago, unpag. Excerpt.

Sentence #55, 56: Edith Farnsworth, “The Poet and the Leopards,” in Northwestern Triquarterly, Fall 1960, 7. Excerpt.

Sentence #58: Pierro Metaponto, “If in Paradise You Would,” trans. Edith Farnsworth, unpublished, no date. Farnsworth Collection, Newberry Library, Chicago, unpag. Excerpt.

Sentence #61: Susan Stewart, Poetry and the Fate of the Senses (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 112.

Sentence #66: Albino Pierro, “Come Quickly,” in Nu Belle Fatte. Una Bella Storia. A Beautiful Story, trans. Edith Farnsworth (Milano: All’Insgna del Pesce d’Oro, 1976), 49.

Sentence #69: Edith Farnsworth, “Arsenio,” 1969, unpublished poem, Farnsworth Collection, Newberry Library, Chicago. Excerpts.

Sentence #70: Hayden White, “The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality,” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 7, No. 1, On Narrative (Autumn, 1980), 8.

Sentence #73: Clemente Rebora, “Dispersed Days,” trans. Edith Farnsworth, unpublished, no date. Farnsworth Collection, Newberry Library, Chicago, unpag. Excerpt.

All images by Nora Wendl, original hand-drawing on Xeroxed archival material, 8.5 x 11 in. Archival material reproduced with permission of The Newberry Library and Mr. Fairbank Carpenter.