Sacred sites transcend time through association with unique geological features or environmental conditions, and their importance is conveyed through myths and constructed markers. Of known sacred sites, most are long-established yet the rationale for their selection is now forgotten. Archaeologists can interpret such sites, speculating on how they were used, but, despite those conjectures, motives directing site selection and formation remain largely unanswerable.

To explore how sacred sites might be initially charted and their meanings developed, this project uses geomancy to locate ten future sacred sites in the United States. Interactions with those sites are then prompted to initiate a process that generates their sacredness.

Geomancy is a field of inquiry and interpretation based on interpreting the earth’s energies. Depending on the practitioner, it is used either to divine the future by asking questions1 or to identify sacred geometries within landscape.2 Interestingly, neither of those two subfields recognizes the methods of the other as valid. I use both geomantic approaches first to predict the locations of future sacred sites and then to identify the sacred features at those locations.3

Predicting the locations of future sacred sites is a multi-phased process, the first step of which is to cast geomantic charts to determine whether such sites can be located and, if so, how many are possble.

To locate future sacred sites in the United States, I engaged that first step and concluded that there would be ten. I then cast ten sets of ten points on a current map of the United States. Next, lines were drawn sequentially to connect the points in each set. The resulting geometries were analyzed to determine broad patterns and relationships between all the points. Based on that process, ten triangular areas were established by identifying clusters of similar points, such as three of the same cast point (7,7,7) or a sequence of numbers (2,3,4). Those points were plotted in GIS, and the geographic centroid of each triangle was calculated to pinpoint the location of each of the ten future sacred sites.

Locations of future sacred sites within the United States

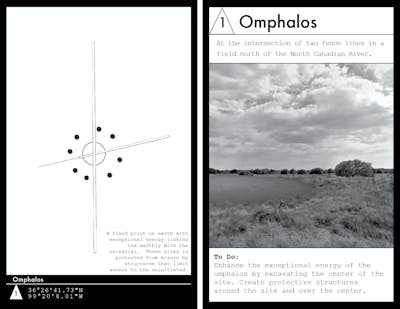

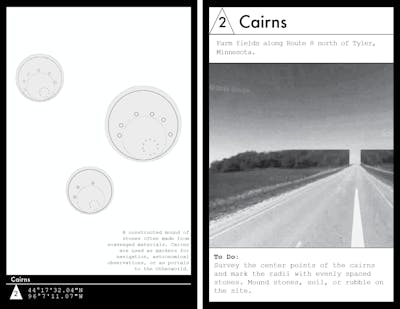

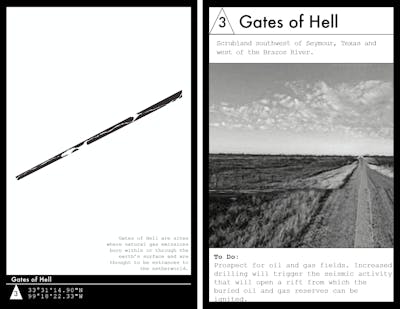

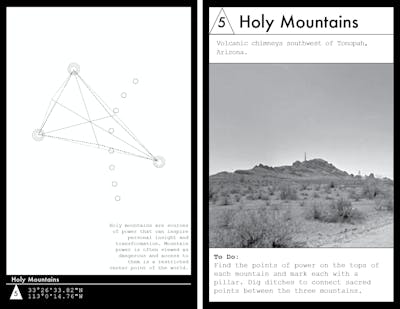

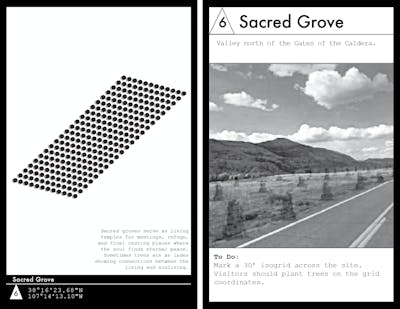

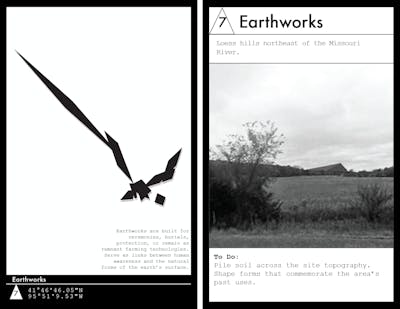

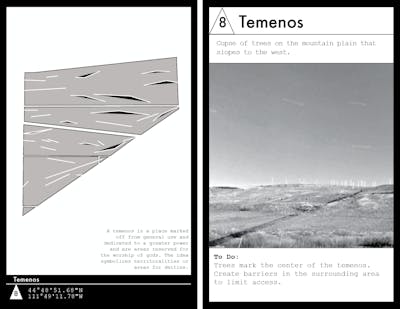

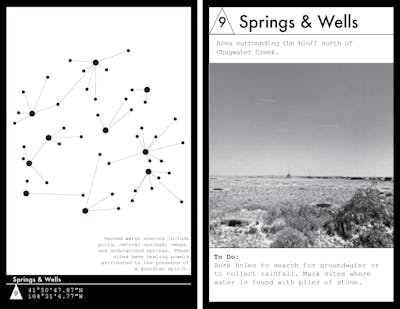

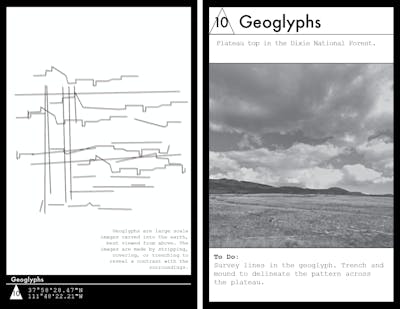

Situating each site geographically provided physical characteristics that were used to guide more specific geomantic inquiries. For each site, multiple geomantic charts were cast asking about the future of the place and what type of sacred elements would come to define it. The geomantic divination predictions were cross-compared with an analysis of each site’s physical characteristics to arrive at a unique sacred geometry for each location. The form for each site was related to a familiar type historically associated with sacred sites: omphalos, cairn, gates of hell, megalith, holy mountain, sacred grove, earthwork, temenos, spring and well, or geoglyph.

Forms for the ten future sacred sites were developed by casting geomantic charts, undertaking geographic analysis, and identifying site-specific sacred archetypes.

The sacred sites and their future forms were then plotted in Google Earth, a platform chosen because of its capacity to render three-dimensional terrain, ease of navigation through dynamic viewpoints, and its historical imagery slider. With the ability to render buildings, objects, and landscape features — including trees — in 3D, Google Earth has the potential to become a highly detailed, if not real-time enabled, digital version of the physical world. Mapping future sacred sites in Google Earth provides the most digital longevity and the potential to see the sites change through time as geospatial data collection, computation, and visualization continue to become more sophisticated.

Satellite views of the ten future sacred sites

The sacred sites and areas located in Google Earth inform the Sacred States of America map, which charts the remains of sacred infrastructures that exist in the distant future with implications for reformed territories. Supplementing the Google Earth file is a printable pilgrimage map and corresponding social media campaign that directs tourists to the Sacred States of America to initiate the process of transforming and developing meaning in those landscapes.

Future Sacred Sites Tourist Cards

Images can be printed and folded along the dashed line, with the blank, inside space used for notes.

Sacred States of America Pilgrimage Map

Downloadable pdf file can be printed double-sided for use as a guide in travel.

Click here for map.

Sacred States of America on Google Earth

User must have Google Earth application to access.

Click here to download .kmz file for use on Google Earth.

Review

By Jesse Vogler

Architecture, in its positivist and materialist aspirations, has long had an uncomfortable relationship with divination. From the Roman augur, to the nineteenth-century land booster, to the twentieth-century real estate salesman, architecture’s foundings have long relied on auspicious narrators of profit or doom. The ancient Roman historian Livy, commenting on what he knew to be always, already at stake in the projective project of architecture, asked: auspiciis hanc urbem conditam esse, auspiciis bello ac pace domi militiaeque omnia geri, quis est qui ignoret? [Who does not know that this city was founded only after taking the divinations, that everything in war and in peace, at home and abroad, was done only after taking the divinations?].4 Who does not know, indeed. Or, rather, how is it that we have forgotten? And so we might reframe the geomancy that gives us the Sacred States of America as a pragmatic divination — one that, as Virgil reminds us, does not rest on the inspiration of the oracle but on knowledge and execution of a skillful system.5

And perhaps it is here, in carrying out the meter of an epistemic technology, that divination and modernity converge. The framework that brings us the omphalos, the megalith, the sacred grove, and the temenos is perhaps not as far as we might think from that which gives us the point grid, regulating lines, and the abstract geometry of the modern city. Reading and responding to the flight of birds, on one hand, and the flight of capital, on the other: each of those practices depends on faith.

But still, we are told to cast our lot with the rationalist diagrams of modernity over these agents of conjecture. Hartman has cast her lot differently, as have I, and she invites us to join in a new founding, from which we can measure our distance in space, time, and orientation from an estrangement that may not be quite as neat as we originally suspected. After all, what is it that we provide, what particular currency is it that we architects circulate, if not that divine scrip of speculation?

Notes

1

John Michael Greer, Earth Divination, Earth Magic: A Practical Guide to Geomancy (St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 1999).

2

Nigel Pennick, The Ancient Science of Geomancy: Man in Harmony with the Earth (London: Thames and Hudson, 1979).

3

For a more in-depth discussion on geomantic divination as a tool for landscape inquiry, see Ellen Hartman, “Savior City,” in (Non-)Essential Knowledge for (New) Architecture [306090 15], ed. David L. Hays (Princeton, NJ: 306090/Princeton Architectural Press, 2013), 50 – 79.

4

Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book VI, Chapter 41.

5

See Justus Frederick Holstein, Rites and Ritual Acts as Prescribed by the Roman Religion According to the Commentary of Servius on Vergil’s Aeneid (Thesis, New York University, 1915; New York, NY: Voelcker Bros., 1916).

Biographies

Ellen R. Hartman is an artist, designer, and researcher trained in architecture and landscape architecture. She researches landscapes for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and is co-founder of the design research collaborative Studio Ha-Ha. As a researcher, Hartman’s work focuses on the intersection of social and environmental networks in urban areas and generates pages and pages of technical reports. As a designer, her primary interest is collaging the historical, the fantastical, and the absurd. In 2008, Hartman became a geomancer through an online course and has since used geomancy in her design work as a tool for investigating what she does not know. Her geomantically-influenced work “Savior City” was featured in (Non-)Essential Knowledge for (New) Architecture (306090/Princeton Architectural Press, 2013). Email: ellen.hartman@gmail.com

Jesse Vogler is an artist and designer whose work sits at the intersection of spatial practices, material culture, and political economy. Drawn to questions that attach themselves to the periphery of architectural production, his projects take on themes of work, law, property, expertise, and perfectibility. Recent projects include a series of exhibits on the administrative landscape with The Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI), a performative project on commoning with the Center of Contemporary Art Tbilisi, a set of site-specific installations at PLAND, and a collaborative, multi-platform project of critical geography centered on the American Bottom. Vogler’s work has been supported by awards from the Graham Foundation, Mellon Foundation, MacDowell Colony, and the Fulbright Scholar Program and has been exhibited at the Venice Architecture Biennale, the CLUI, the Center for Contemporary Arts Santa Fe, and the Urban Institute for Contemporary Arts. Recent publications featuring his writings and work include [bracket], MONU, Ground Up, Artforum, Domus, and the Los Angeles Times. In addition to his art practice, Vogler is a land surveyor, co-directs the Institute of Marking and Measuring, and is an assistant professor of landscape architecture in the Sam Fox School, Washington University in St. Louis. Email: jessevogler@gmail.com