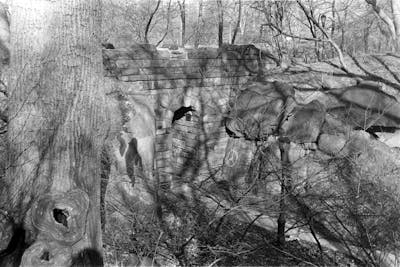

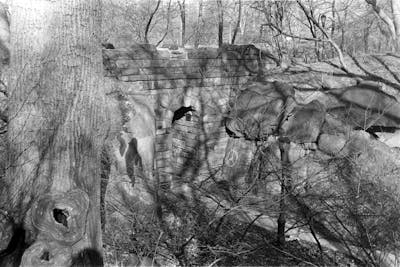

Site model of the Central Park Ramble, produced by the City College MLA Studio 1, Fall 2011.

Image courtesy of Liza Trafton.

Sometimes there is buried treasure in an archive, which for me might be defined as something that no one has really thought about or read in a long time but that perhaps should be re-read today. And I think it’s often useful to bring this kind of forgotten work out again, for others to read and reflect upon, at a different moment in time.

In July 2011, I spent a number of hot afternoons on the second floor of the Arsenal in Central Park, looking for anything I could find about the Central Park Ramble in the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation’s Library. This was due diligence research for an upcoming fall semester design studio, the introductory course for Master of Landscape Architecture students that I teach each fall at the City College of New York. I didn’t really know exactly what I was looking for. Surprisingly, the Library’s archive isn’t particularly impressive — a pair of filing cabinets in a hallway and a few stacked cardboard boxes maintained by Kaitilin Griffin, the Parks Department’s Librarian. Like many at the Parks Department, Kaitilin wears many hats; for example, she is also responsible for the implementation of a sedum green roof and garden on the Arsenal’s rooftop. Responding to my phone call, Kaitilin gave me an appointment time and pulled out a stack of manila envelopes filled with articles and newspaper clippings about the Ramble.

Among the documents put into my hands was a gem: a July 1979 report entitled “Central Park Ramble: A Study of Visitors’ Evaluation of Landscape,” by Don S. Cook. The research for this report, consisting mostly of on-site interviews of people in the Ramble, was conducted by Cook under contract to the Central Park Task Force as part of the preparatory work for a proposed restoration of the Ramble. Interestingly enough, there was a funny connection to City College: Cook wrote the study as part of his work as an ethnoscientist with the Center for Human Environments (producing the wonderful acronym CHE), a research arm of the City University of New York’s Graduate Center. Thirty-six years later, CHE is still active within the Graduate Center, and its mission is to unite researchers who examine relationships between people and their physical settings. CHE is now organized as a consortium of eight specialized sub-groups, each examining topics such as children’s environments, public space, housing, and health.

The discovery of Cook’s “Study” was a wonderful pleasure. It’s quite unusual to find an archival text that feels so pertinent and fresh — and since this one includes transcriptions of conversations, it really felt like the document was speaking to me. I was immediately hooked. “Study” is something of a period piece, a document in which the author thanks his typist in the acknowledgments, along with the Central Park Task Force that commissioned the work. Interestingly, I had just re-read Robert Smithson’s brilliant essay on Central Park, “Frederick Law Olmsted and the Dialectical Landscape,” also written in the 1970s and including Smithson’s impressions of the park’s latent geology, as well as his expressions of nervousness as he ducks a potential mugger by entering the Ramble. Of course, during the 1970s, New York City was bankrupt, crime was rampant, and Central Park was looking particularly neglected. Smithson captured that moment well with his photographs and impressions, as did Cook with his transcribed interviews.

In addition to the library in the Arsenal, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation maintains a photographic archive at its rather marginalized design headquarters, the Olmsted Center, in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, Queens. Arriving there after a long ride on the 7 train, once again searching for an unknown something for the upcoming studio, I flipped through thick, black, three-ring binders packed with photographs in archivist Christina Benson’s tiny, over air-conditioned office. The binders were organized by park number and decade, and the M‑10 (Central Park) set revealed a cultural timeline: 1950s, photographs of parties and masquerade gondola races on the lake; 1960s, beatniks and hippies hanging out around the Bethesda Fountain and participating in Happenings and Be-ins. And then there was the 1970s binder: detailed close-up photos of damage and decay — broken steps, crumbling stone bridges, graffiti — and muddy-bottomed lakes. The city (and therefore, Central Park) was broke.

Cook describes his document as a behavioral study, the aim of which was conveyed by its subtitle: to understand how people perceived the landscape of the Ramble. After analysis and interpretation of the field interviews, Cook organized his data into six themes, which he called “domains,” revealing aspects of the experience of the Ramble which were meaningful to visitors: Natural, Run Down, Secluded, Gathering, Lost, and Safety. As a self-described ethnoscientist, Cook was particularly interested in the relationship between qualities of the landscape and the behavior of visitors. He explained that the six themes were not mere descriptions of the landscape but prioritized impressions delivered through visitors’ particular frames of reference.

Perhaps what is so compelling about Cook’s study — excerpts of which are reproduced below, along with contemporaneous photographs from the NYC Parks Department archive — is the snapshot of the people he encounters in the Ramble over a few days in May and June 1979, people who really engage with the park. No matter its “run down” qualities, Cook’s interviewees love Central Park and are particularly insightful when discussing the “place” of the Ramble. As a landscape architect, it is delightful to read their answers to Cook’s repeated question: “What kind of place is this?” Indeed, Cook is somehow reminding us that we should ask ourselves that question over and over — of the spaces we love, the places we wish to create, the environments and niches we carve out from our city. We should ask this of ourselves as well as others, questioning our own perceptions of place. What kind of places do we want to create, to extract or insert into our city, and perhaps one day ramble through, semi-lost? And what are our new “domains?” Perhaps we could start considering our city’s public spaces through some of these contemporary categories: Novel, Queer, Occupy, Zone 1, Narcisstick, Hashtag, Stop and Frisk. What priorities would be revealed by interviews with Ramble occupants now?

Special thanks to both Kaitilin Griffin and Christina Benson of the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

Note on the format of the transcribed interviews: Q, the questioner, is always Don S. Cook. M and F refer respectively to male or female interviewees. A and B are interviewees of the same gender. The date of each interview and descriptions of the interviewees were provided by Cook.

Ramble Domain #1

“NATURAL”

Norman arch at the western entrance to the Ramble, c. 1973.

Image courtesy of New York City Parks Photo Archive.

Q What kind of place is this?

A … right here I feel like it’s a chance to get back to something wild and natural. I like these parts of the park a lot where there’re paths winding through and the trees are pouring over and it’s sort of disorganized and real, you know.

B That’s what, it’s a chance to get to something that’s sort of real after spending all week in the not very real environment.

Q You mean the city?

B In the city, yeah…

…

A … The trees and stuff just the way it is is fine. Just fine… I know things were planned, I know this park was very carefully planned, and probably more carefully planned than Versailles was planned, but now that it’s been a period of time it doesn’t look it was planned…

[20 May 1979, #3. Two women, strolling.]

_______________

A … I like these outcroppings of rocks and the much bigger ones all over, to me this is what nature should look like.

[20 May 1979, #4. Elderly man sitting on bench.]

Ramble Domain #2

“RUN DOWN”

The Lake and the Ramble, Central Park, ca. late 1970s.

Image courtesy of New York City Parks Photo Archive.

A And this is a really nice area in here, but it’s always shitty, it’s always yucky and stagnant and rats and just yuck.

Q It seems, that seems to kind of contradict itself. Why is it a nice area if it’s always yucky?

A Because you can see that it could be a really nice area, I mean, just the way it is, just the topography of the place, it’s really beautiful. It’s just that the water is what’s yucky.

[17 May 1979, #3. Two men, strollers.]

Ramble Domain #3

“SECLUDED”

Robert Moses-era concrete bridge and steel railing over the Ramble waterfall, 1973.

Image courtesy of New York City Parks Photo Archive.

Q Is this kind of place like Riverside Park? Is it the same kind of place?

M No. It serves the same functions sort of, but it’s different because it’s a bigger area and it has more place to walk that’s secluded.

W Riverside is open.

M Well, it has two basic trailways to walk, you know, one side of the highway and the other, down by the river. Which is different and, you know, nice. Like here we’re walking through the trees.

W You can kind of ramble.

M It gives you a sense of seclusion.

Q The trees do?

M Well yeah. The secluded places.

F Yeah, and the wandering.

M And the wandering… I remember we used to play on the rocks.

Q Do you know if this part of the park has a name?

M I’m sure it does… I don’t know. What is it?

Q I ask lots of people that question and I get different names. So I’m just asking people to see what names I get.

M Central central park.

[15 May 1979, #5. Couple, late twenties, strolling.]

Ramble Domain #4

“GATHERING”

Marchers and onlookers at the Gay Pride Rally, Central Park, July 1975.

Image courtesy of New York City Parks Photo Archive.

Q Tell me, what kind of place is this?

A Well it’s a place where people come when they don’t have anything to do, you know. Like in the summertime. Like they come down here, you know, to get some air, walk around.

B I even go jogging through here.

Q You do?

[15 May 1979, #4. Spanish girls.]

________________

Q You say you know some of the people [in the “Brambles,” a gay gathering place] and you go there too…

A I think everybody’s out on Fire Island today.

Q Oh yeah. Do you ever meet new people there in the meadow?

A Oh yeah. That’s where I met most of the people I know in the neighborhood.

Q Is meeting someone like in that meadow somewhat the same as meeting someone in a bar?

A No. I think they go to bars for different reasons. Over here it’s just like a feminine kind of thing.

[26 May 1979, #3. Two men strolling.]

Ramble Domain #5

“LOST”

Foot of the Angel of the Waters, Bethesda Fountain, Central Park, 1971.

Image courtesy of New York City Parks Photo Archive.

Q Do you mind being lost like that?

M Oh no. I mean I know I’m going to find my way out of here. I mean, if I had definite plans of going in a certain direction, you know, hey, I’m lost, which way am I going to go. But as far as getting lost, you know you can’t get lost. If you go to one end then you go to the other one. You’re either going to come out on the East Side or the West Side, you know.

Q So you’ve been wandering through the park.

M Yeah. Looking for our favorite tree.

(Laughter.)

Q Where is your favorite tree?

M We don’t know or else we would be there. (Laughter.) It’s by the roller rink somewhere. We can’t find it. We’re just lost and we’re just enjoying the view around here.

….

M Where does this go? Do you know where this goes?

Q I’m not sure.

M That looks nice. Let’s go down there.

[5 May 1979, #3. Couple strolling.]

Ramble Domain #6

“SAFETY”

Workers repairing a bench, Central Park, ca. late 1970s.

Image courtesy of New York City Parks Photo Archive.

Q Are there other kinds of uncrowded places?

M There are many here. And on a quiet day I would avoid them as a matter of safety.

…

W … it’s pretty safe wherever you go except it’s best not to go early in the morning or after a certain time in the night when it gets dark, but other than that it’s safe.

M She thinks it’s safe, but I’m on the alert.

Q Are there some parts of the park where you feel more on the alert than others?

M This part [Bonfire Rock]. I’m not really worried, but I’m just watchful.

…

Q Somebody suggested to me at one time that they clear out some underbrush so you can see a little bit farther in the area. What do you think about that?

M Well, it would take away part of the park, literally.

W I would hate them to take away the trees. I would like them to take more care of the trees. Some trees look as if they don’t have care.

[26 May 1979, #1. Man and woman, sixties.]

POSTSCRIPT: Ramble Domain #7?

“RADIOS”

New Year’s Party at Bethesda Fountain, 11.00pm, December 31, 1969.

Image courtesy of New York City Parks Photo Archive.

*A theme insufficiently explored, and therefore not treated at length in this report, was “radios.” The loud playing of portable radios was widely deplored as an “invasion of privacy,” yet the condemnation was not specific to the Ramble. A few carriers of radios were interviewed. The terms they gave the Ramble were similar to those used by others. We do not yet know enough to discriminate between the perception of radio carriers and radio adversaries.

Review

By David L. Hays

In an essay on the forms and uses of history, Friedrich Nietzsche described three highly divergent approaches: monumental, antiquarian, and critical.1 In monumental history, the past is framed as a progress of great achievements. In contrast, the antiquarian approach treats history as a comprehensive record of the past; information is gathered without discrimination, as if every bit were of equal significance. Nietzsche clearly preferred critical history, which asserts the right of people to assess the past in terms of consequences and to judge forebears accordingly. Yet, there’s something fascinating about the antiquarian impulse to archive everything, aspiring to objectivity by suppressing the filters that bias recollection. Of course, the form and methods of the archive determine what can be encountered there; the medium is part of the message. Nevertheless, in treating all information as potentially valuable, the antiquarian pretense of neutrality dovetails neatly with critical insistence on assessment and judgment. In other words, both pertain to meaningful practice of history.

History is not the past. It is interpretation of the past through frameworks of the present. History is always made in the present. In “Ramble Landscape,” Seavitt Nordenson makes history by recounting her discovery of materials in two archives, assembling a selection for publication, and interpreting their significance. Her inquiry began with a ramble in an archive, seeking “an unknown something” about the Ramble in Central Park. Archives are usually approached in pursuit of specific information, but they are also places of serendipitous discovery, and they can be explored for pleasure. For Seavitt Nordenson, finding Cook’s report, and later the photographs, was “a wonderful pleasure.”

“Ramble” is both a noun and a verb. In either form, it refers to a way of proceeding without a pre-defined route. A ramble may come of confusion, but it can also occur en route to some preconceived end, such as pleasure or “searching for an unknown something.” “Ramble” depends on uncertainty, the imminence of the unexpected. As act and action, it is contingent on contingency.

Dictionaries define rambling as a way of walking, talking, or writing, but it is also a way of reading. A text is not a ramble, but any text can become one through reading. Similarly, any landscape can support rambling, though some are more conducive to unexpected encounters. Cook registered that condition through his experiences in the Ramble. In transcribing visitors’ speech, he gave them voice, and they offer impressions somewhat different from the familiar narrative. From that, Cook outlined a set of “domains,” priorities and concerns particular to that moment, and Seavitt Nordenson in turn suggests domains for our own moment. In both cases, the work points to the value rambling — of proceeding without a pre-defined route — as a productive aspect of historical method.

Notes

1

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life [Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben], trans. Peter Preuss (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Co., 1980; 1st German edition, 1874).

- Tags

- placelandscapehistory

Biographies

Catherine Seavitt Nordenson is an associate professor of landscape architecture at City College of New York and principal of Catherine Seavitt Studio. In both capacities, her research and writing during the past decade have focused on adaptive design related to climate change, with special emphasis on rising sea-levels. With engineer Guy Nordenson and architect Adam Yarinsky, she co-authored the 2007 Latrobe Prize study On the Water: Palisade Bay, a project that led to the MoMA workshop and exhibition Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfronts (2010), with On the Water published as a corollary book (Hatje Cantz Verlag/MoMA, 2010). Seavitt Nordenson and her collaborators have since extended their inquiry to the Mississippi River and Yangtze River deltas. Also, as the principal investigator at City College for “Structures of Coastal Resilience,” a research project funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, Seavitt Nordenson has developed an analysis and set of proposals for Jamaica Bay, an estuary at the southwest end of Long Island and adjacent to Brooklyn and Queens, NY. Email: cseavitt@seavitt.com

David L. Hays is co-editor of Forty-Five, Associate Head of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and founding principal of Analog Media Lab. Trained in architecture and history of art, his scholarly research explores contemporary landscape theory and practice, the history of garden and landscape design in early modern Europe, interfaces between architecture and landscape, and pedagogies of history and design. Hays is the editor of Landscape within Architecture (2004) and (Non-)Essential Knowledge for (New) Architecture (2013), both by 306090/Princeton Architectural Press. His essays have appeared in a wide range of journals — including Harvard Design Magazine, PLOT (City College of New York), Eighteenth-Century Studies, The Senses and Society (Oxford), Matéricos Perifericos (Rosario, Argentina), Tekton (Mumbai), and Feng jin yuan lin and Landscape Architecture China (Beijing) — and as chapters in numerous books. As a designer, Hays’s work explores the production of environmentally responsive objects using low-cost, low-tech materials. With particular interests in dynamic systems, environmental phenomena, and craft, his process crosses lateral thinking and intuition with grounded experiment. Email: dlhays@forty-five.com