Introduction

Among the more than 9 million U.S. patents granted since the Patent Act of 1790, a representational anomaly exists in which intellectual property and place converge in an evocative yet confounding hybrid at the interstices of technology and environment. For good reasons, known geographical locations are rarely represented in patent documents. The specificity of place precludes the widest interpretation of patent claims and is, therefore, generally omitted from texts and images that aim to protect the broadest interpretation of intellectual property. Besides, direct correlation between the configuration and function of a novel invention and a specific location, landscape, or environmental condition is atypical — obviously. Yet, the schism between patent and place is not absolute, and a unique subset of patents granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) includes texts and images that suggest site specificity within intellectual property claims.

Patent, Representation, and Environment

Patents have operated as an invisible landscape-of-power in the built environment since the Italian Renaissance, when the world’s first patent was issued to the eminent architect Filippo Brunelleschi in 1421 for a “machine or ship” and method of transporting materials for his Duomo of Florence, establishing seminal legal and architectural precedents.1 Brunelleschi’s patent protected his invention of a new machine and method for transporting heavy loads by water, solving one of three major engineering problems associated with his novel dome construction processes.2 Although the patent’s legalese and the dome’s structure operated independently on discrete legal and structural principles, they formed together a highly interdependent and deterministic mechanism governing the form of the built environment. In this manner, the patent — western civilization’s oldest legal and institutional mechanism for incentivized innovation — has long mirrored, defined, and shaped the built environment, yet failed to represent it eidetically in a way that is commonly recalled.3

Patents do parallel the built environment and design thinking. In his book The New Architecture and the Bauhaus (1935), the modernist architect and theorist Walter Gropius foretold the transformation of architecture and design through industrial process, and, true to form, he and his business partner Konrad Wachsmann secured a U.S. Patent for a “Prefabricated Building System” (US2355192) in 1942, applying Bauhaus principles to contemporary housing problems.4 Just a few years earlier, in 1938, Stanley Hart White, a professor of landscape architecture at the University of Illinois, unified new steel structural principles with advances in hydroponic technology to create a vertical garden model called the “Vegetation Bearing Architectonic Structure and System.” Correlating modern landscape theory to U.S. Patent claims, White’s invention was a truly modern accomplishment in the context of academic Beaux Arts.5 This coevolution of patent development and the built environment can also be traced through other complex infrastructural and natural systems, such as rivers, coasts, cities, buildings, and designed landscapes.6

A patent is, in essence, a representation of a specific invention. U.S. patents have been accompanied by models, drawings, and textual descriptions since the Patent Act of 1790, which established American patent law and pertinent representational standards.7 The Patent Act states that grantees shall deliver to the Secretary of State, Secretary of War, and Attorney General “a specification in writing, containing a description, accompanied with drafts or models, and explanations and models (if the nature of the invention or discovery will admit of a model) of the thing or things, by him or them invented or discovered.” If the invention was found to be new and valuable by the cabinet secretaries and the Attorney General, the patent was granted and signed, bearing ultimately the “teste” of the President himself. In that manner, the government and inventors coevolved the technological substrate of “the arts” towards unforeseen ends. Patent law places no restriction on what may be invented or what might be deemed useful or valuable among the arts, opening up a world of possibilities limited only by the ingenuity of the citizenry and the representational standards of the patent, which today is global, territorial, nanoscale, atmospheric, and even astronomical in reach.

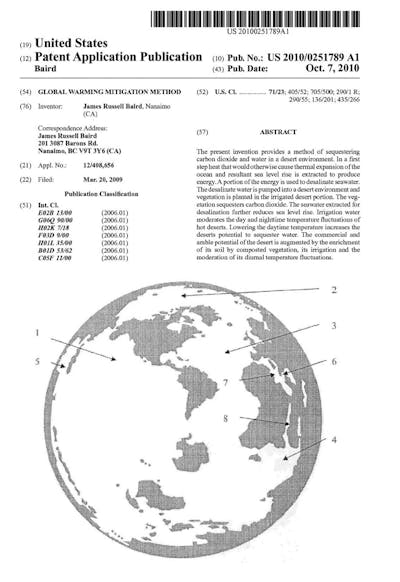

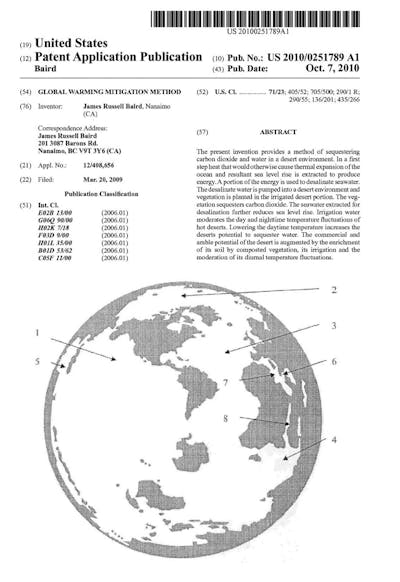

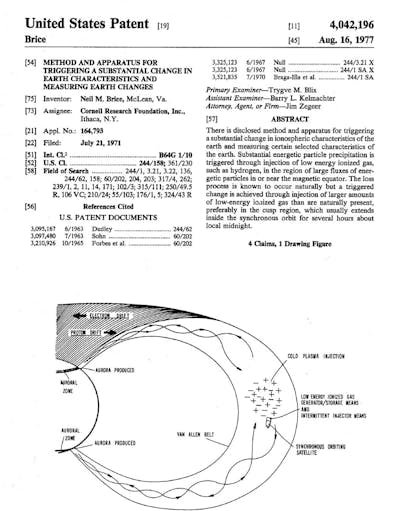

Figures 1a‑b: Patents disclose innovation across a range of scales, from nanoscale materials to systems for geoengineering and manipulation of atmospheric systems. Patent documents are currently formatted on 8.5” x 11” sheets, with black and white line drawings and text, making issues of scale particularly salient. The patents shown here operate at the largest known scales for patent innovation.

1a: James Russell Baird, “Global Warming Mitigation Method” (U.S. 2010/0251789).

1b: Neil M. Brice, Cornell Research Foundation, “Method and Apparatus for Triggering a Substantial Change in Earth Characteristic and Measuring Earth Changes (U.S. 4,042,196).

Most patents related to landscapes, rivers, cities, regions, coastlines, and other complex environmental systems are intentionally site-less, distancing intellectual property claims from any specific locations. Patents of this sort typically use diagrammatic or typological drawings to disclose inventions and protect the widest possible scope of intellectual property claims while maintaining ambiguity as to where the patent might be applied.

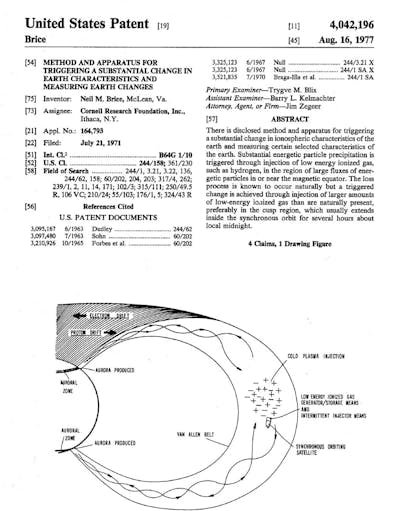

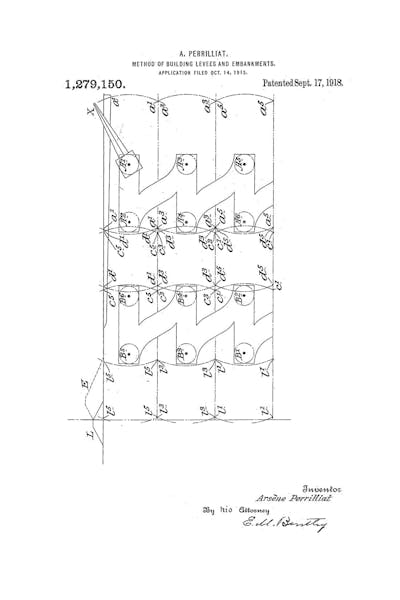

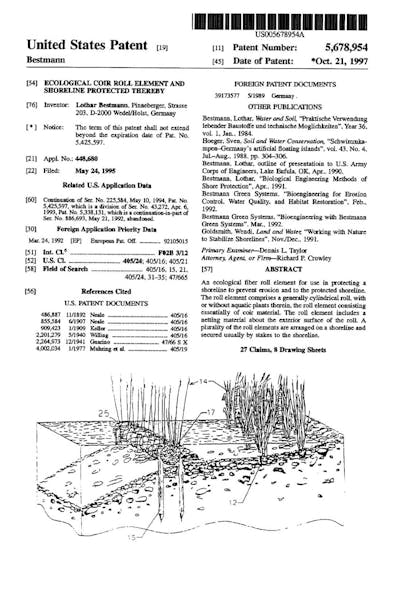

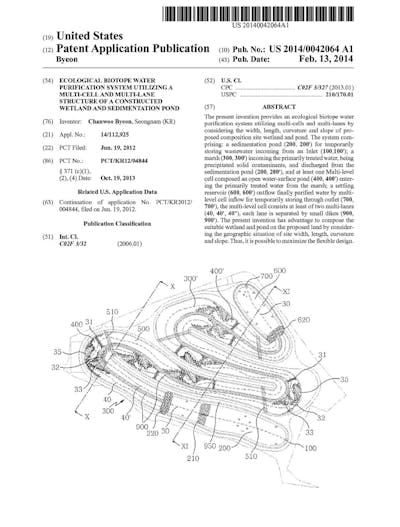

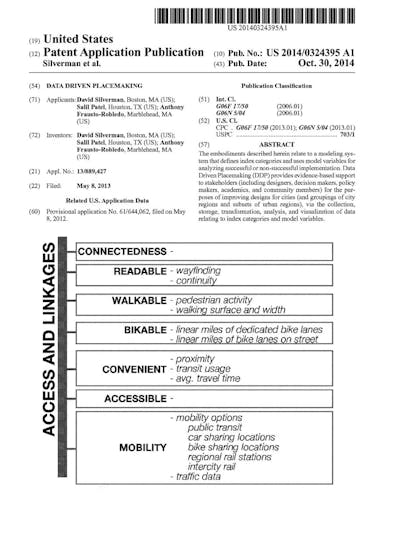

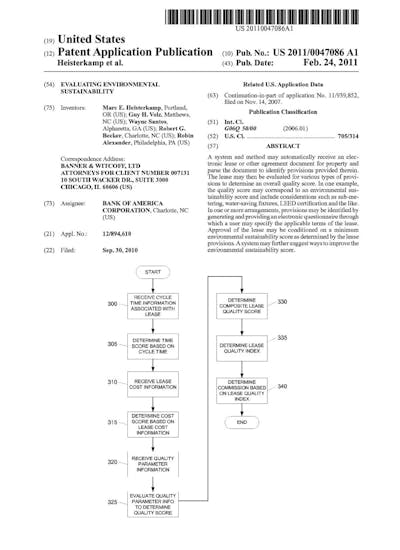

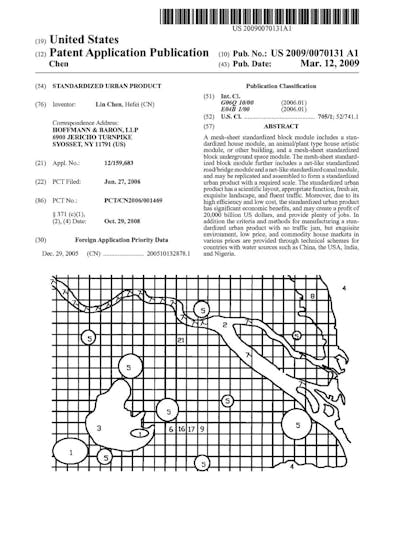

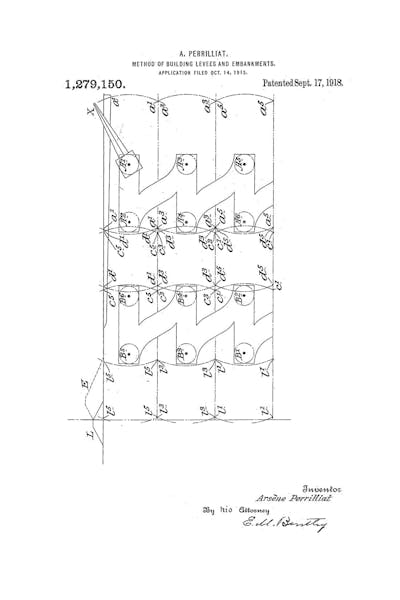

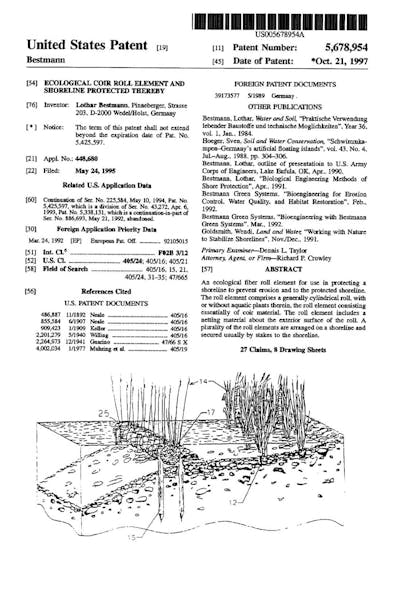

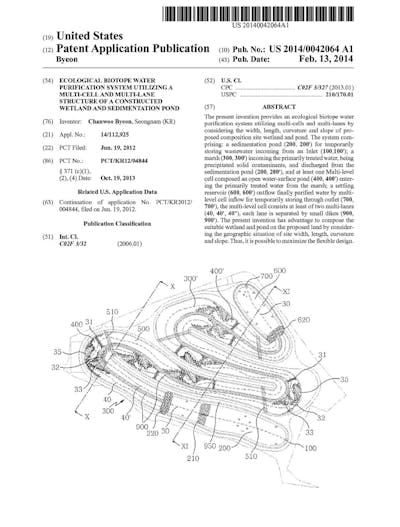

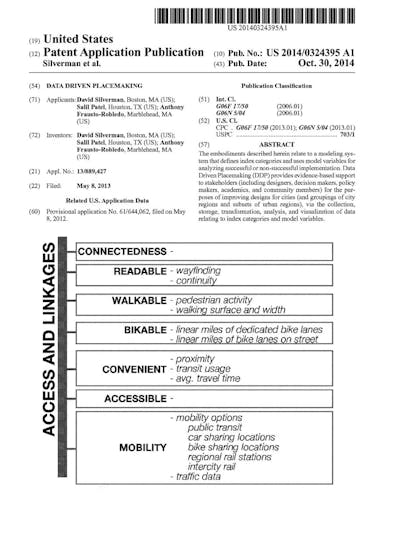

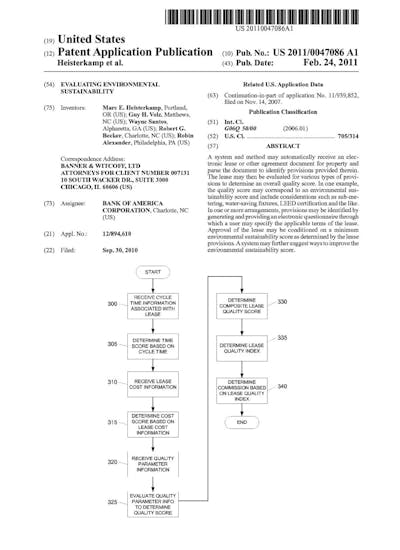

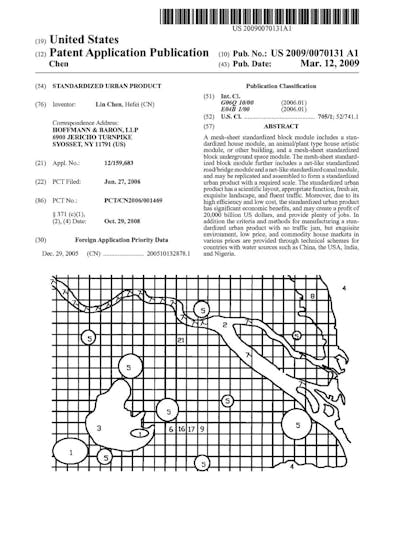

Figures 2a‑f: The built environment is often represented in patent documents as a siteless series of typological conditions, material assemblages, processes, and methodologies. The patents shown here disclose inventions for (2a) choreographing earth moving and building levees, (2b) constructing unique water/terrestrial edge conditions (U.S. 5,678,954), (2c) controlling the ecological flow of water and sediment (U.S. 2014⁄0042064), (2d) utilizing data for placemaking (U.S. 2014⁄0324395), (2e) evaluating sustainability (U.S. 2011⁄0047086), and (2f) generating urban form (U.S. 2009⁄0070131). They are siteless, yet potentially impact the built environment.

2a: Arsène Perilliat, “Method of Building Levees and Embankments” (U.S. 1,279,150).

2b: Lothar Bestman, “Ecological Coir Roll Element and Shoreline Protected Thereby” (U.S. 5,678,954).

2c: Chanwoo Byeon, “Ecological Biotope Water Purification System Utilizing a Multi-Cell and Multi-Lane Structure of a Constructed Wetland and Sedimentation Pond” (U.S. 2014/0042064).

2d: David Silverman, Salil Patel, and Anthony Frausto-Robledo, “Data Driven Placemaking” (U.S. 2014/0324395).

2e: Marc E. Heisterkamp, Guy H. Volz, Wayne Santos, Robert G. Becker, and Robin Alexander, “Evaluating Environmental Sustainability” (U.S. 2011/0047086).

2f: Lin Chen, “Standardized Urban Product” (U.S. 2009/0070131).

Those drawings cover a range of design thinking and processes — describing workflows, evaluative methods, detailed material configurations, gadgets of one kind or another, and a dizzying array of objects — ultimately representing the environment as a series of typological conditions, tectonic assemblages, data sets, and operations often contingent on specific spatial or physical conditions yet, in essence, without specific sites.

The siteless quality of environmental patent documents does not diminish their potential impact on large-scale complex systems. Consider, for example, the design and construction of Eads’ Jetties at the South Pass of the Mississippi River, near Fort Jackson, a patented system realized between 1875 and 1879 and credited with saving the Port of New Orleans by sustaining commercial activities along the Mississippi.

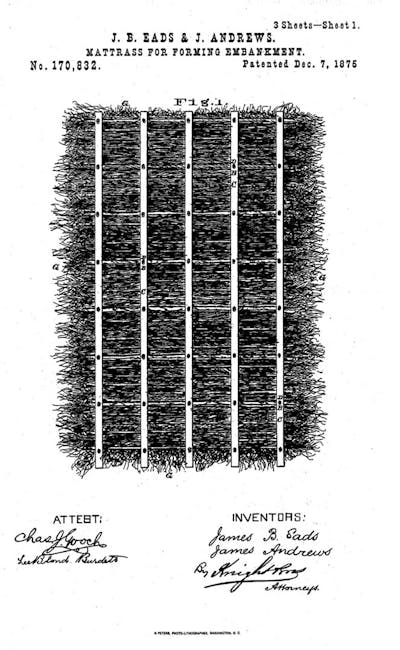

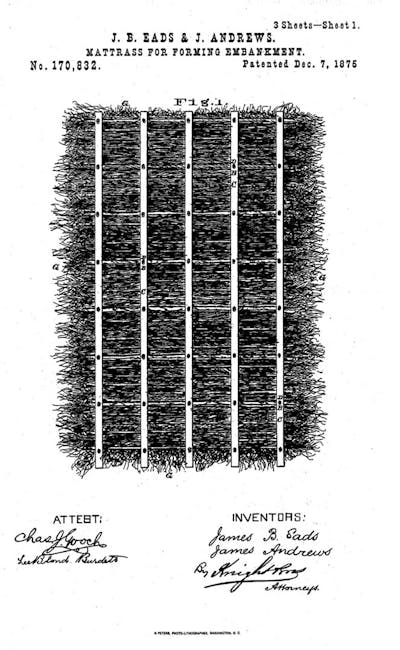

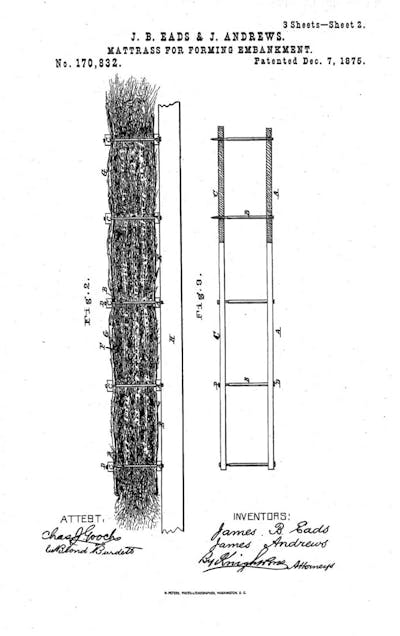

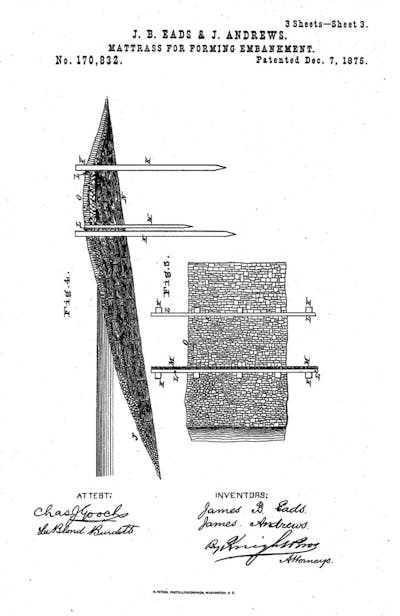

3a: James Buchannan Eads and James Andrews, “Mattrass for Forming Embankment” (U.S. 170,832), sheet 1 of 3; prototyped, tested, and installed at the South Pass of the Mississippi River.

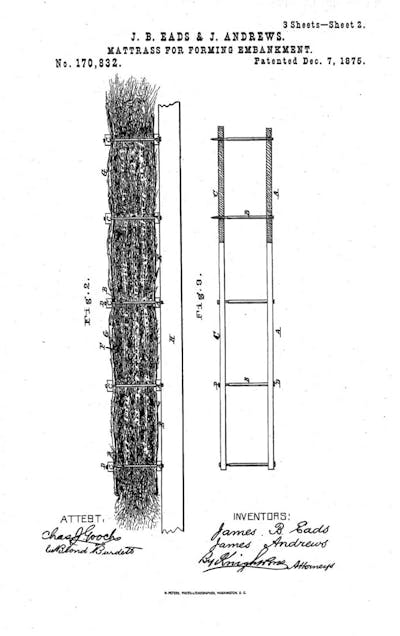

3b: James Buchannan Eads and James Andrews, “Mattrass for Forming Embankment” (U.S. 170,832), sheet 2 of 3.

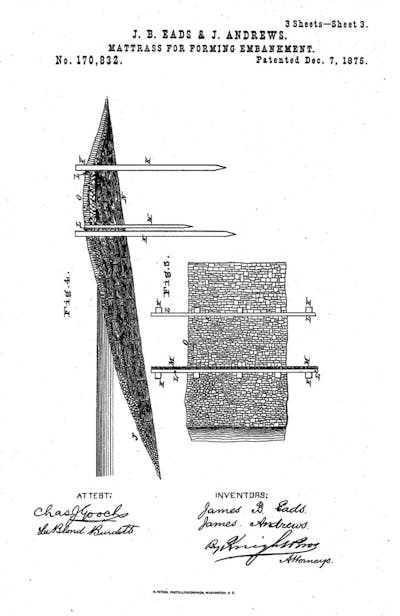

3c: James Buchannan Eads and James Andrews, “Mattrass for Forming Embankment” (U.S. 170,832), sheet 3 of 3.

James Buchannan Eads and his business partner James Andrews prototyped and tested their jetty system at full scale for four years before receiving their fee for the maintenance of a navigable channel at the mouth of the Mississippi, radically altering the fluvial geomorphology and ecology at the Head of Passes.8 The patent granted to Eads and Andrews was designed to suit the unique conditions at the Heads of Passes, yet the document itself makes no mention of this specific location, referencing only environmental conditions common to deltaic landscapes and a method of construction. We know of the patent’s use through Eads’ petitions to Congress and detailed histories of the jetties, but the patent itself makes no reference to a known geographical location. Eads’ patent may be siteless, but its imprint on a specific landscape is bound to the fabric of culture and remains legible today in the morphology of the Mississippi River.

Site Specific Intellectual Property

The anomaly of site-specificity in patents weaves a distinct narrative through geographies of the American landscape dating back to the earliest days of the Patent Office. In this nascent area of environmental innovation studies, I propose Thomas Paine as the first person to submit site-specific works to the patent office, though we may never know for sure about that precedence as most of the earliest American patents were destroyed in a fire in 1836. Paine never built a steel bridge in America, contrary to what was suggested in correspondence with Thomas Jefferson. He did, however, propose bridges in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania a short time after his book Common Sense (1776) helped catalyze the American Revolution. Models of Paine’s designs for bridges spanning the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers were exhibited in France and England prior to being sent to the U.S. Patent Office for dissemination and safekeeping, establishing the earliest known precedent for site-specific works curated by the patent office.9

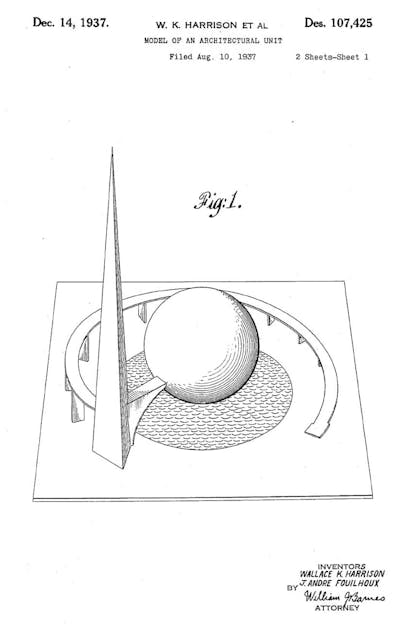

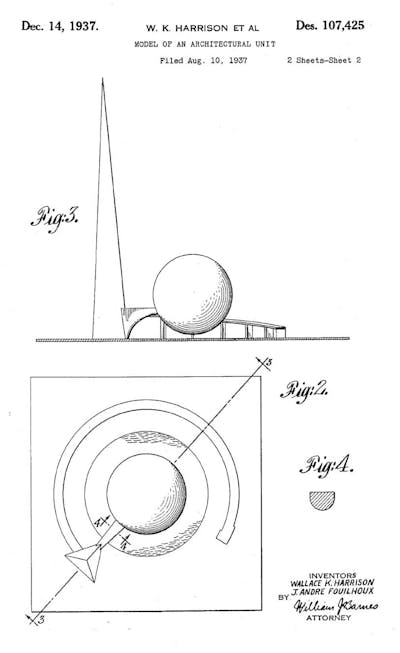

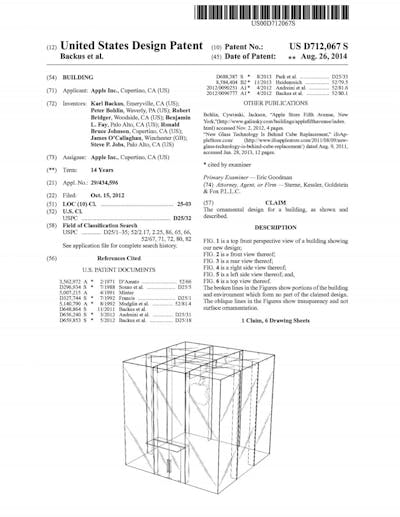

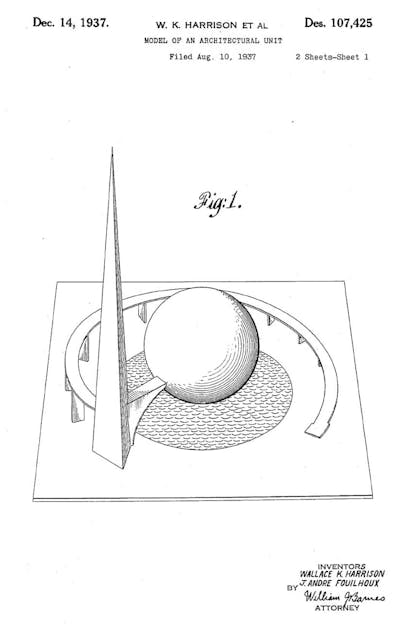

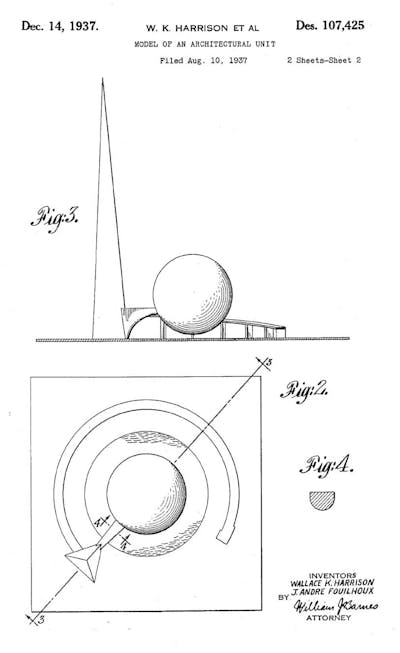

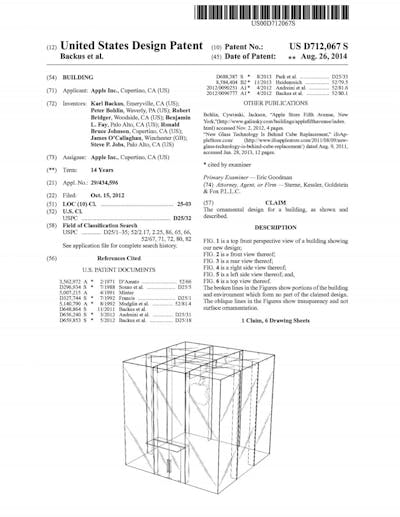

Although the models mentioned in Paine’s writings were probably destroyed in one of several conflagrations of the Patent Office, we can reflect on the confounding intersection of intellectual property and place, or real property, and trace a lineage to the environmental challenges of today. Paine’s submission of bridge models to the U.S. Patent Office was not an isolated instance of site-specificity within the annals of patent history. In fact, many site-specific works have been premised on intellectual property of one sort or another. These proposals range in scale and scope from design patents that protect the form and appearance of specific buildings, such as architect Wallace Harrison’s patent for models of the Trylon and Perisphere (New York World’s Fair, 1939 – 1940) and Apple Inc.’s patent for its store on Fifth Avenue in New York City, to utility patents for systems that aim to reconfigure the function and performance of cities, regions, and ecosystems.

4a: Wallace K. Harrison et al., “Model of an Architectural Unit” (U.S. Des. 107,425), a patent limiting replication of the form of the Trylon and Perisphere designed and built as a central feature of the New York World’s Fair (1939-1940), sheet 1 of 2.

4b: Wallace K. Harrison et al., “Model of an Architectural Unit” (U.S. Des. 107,425), sheet 2 of 2.

4c: Apple Inc., “Building” (U.S. D712,067), a patent protecting the design of Apple Stores from replication, based on the flagship store on Fifth Avenue in New York City. Design patents protect form and appearance; utility patents protect the function and configuration of an invention.

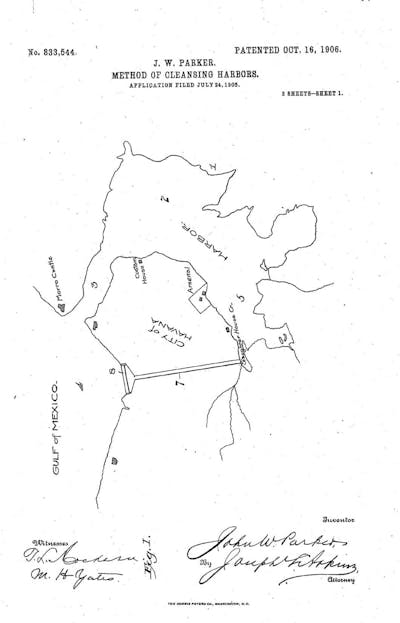

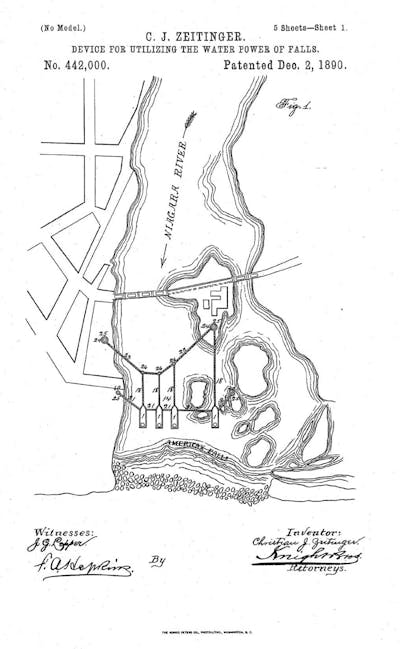

Speaking generally, the siteless quality of patents has obscured an intimate relationship between known places and specific technologies. One may easily miss the relationship between patent and place when surveying millions of documents, which at first glance appear as a treasure trove of things — gadgets, machines, and objects — but not of the environment as a whole, a place, or any known geography. Cartographic forms of representation within patent documents quickly reorient the mind to the potential intersections of intellectual property and environment through the familiar imagery of maps.

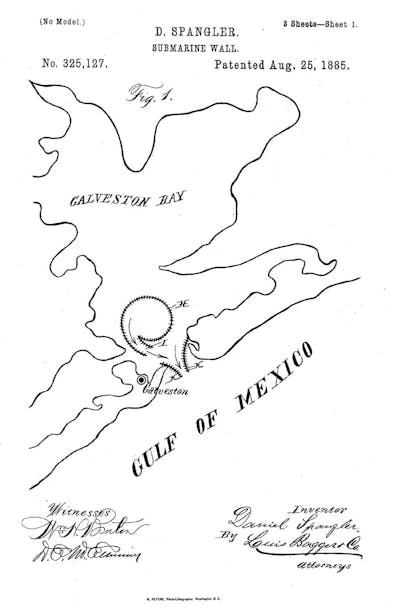

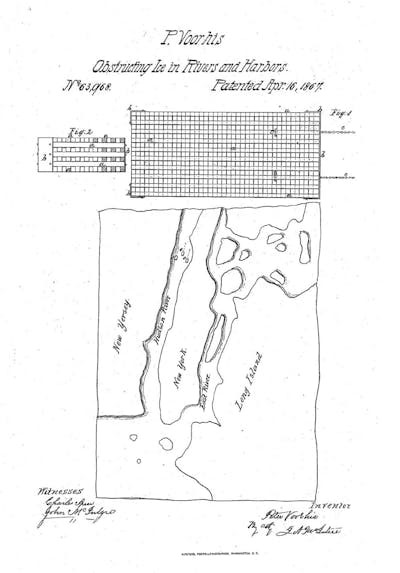

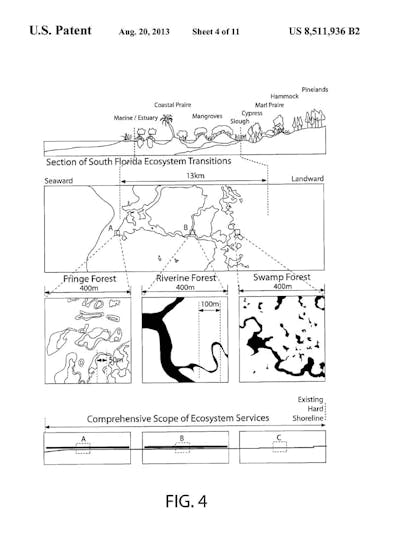

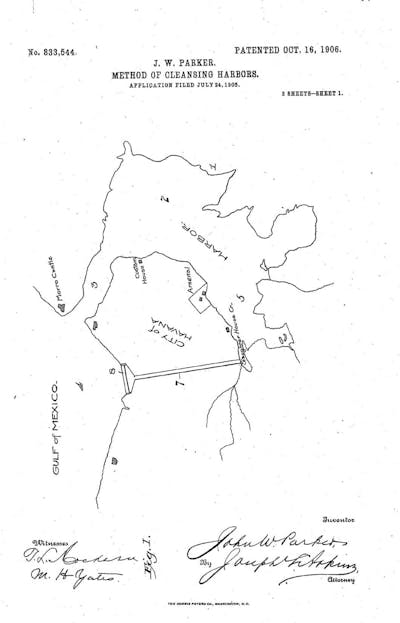

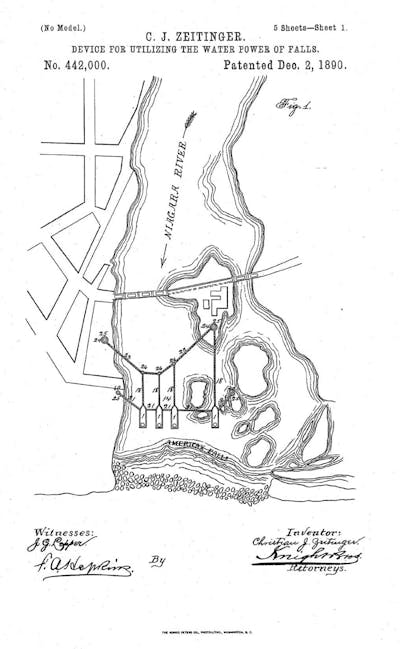

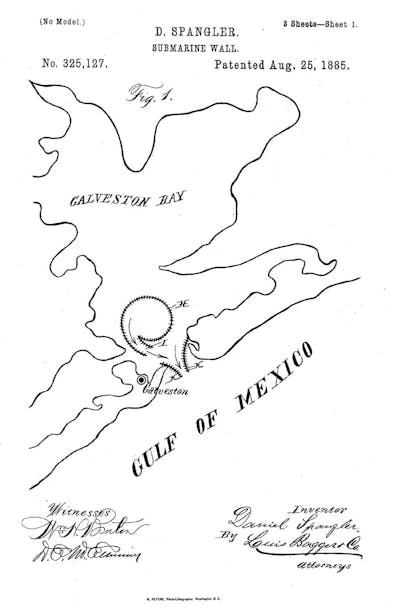

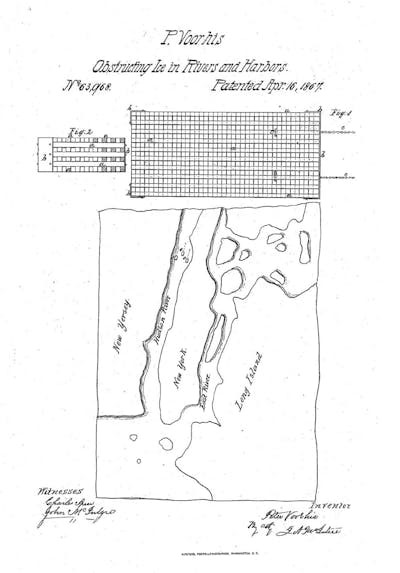

Figures 5a‑e: Patent cartographies situate technological innovations within known geographical locations. Examples of environmental and technological innovation in patent documents include (5a) “Method of Cleaning Harbors,” sited in Havana, Cuba; (5b) “Device for Utilizing the Water Power of Falls,” sited at Niagara Falls, New York; (5c) “Submarine Wall,” sited in Galveston Bay; (5d) a method of “Obstructing Ice in Rivers and Harbors,” sited in New York City; and (5e) “Method and apparatus for coastline remediation, energy generation, and vegetation support,” sited in global mangrove ecosystems.

5a: John W. Parker, “Method of Cleaning Harbors,” sited in Havana, Cuba (U.S. 833,544).

5b: Christian J. Zeitinger, “Device for Utilizing the Water Power of Falls,” sited at Niagara Falls, New York (U.S. 442,000).

5c: Daniel Spangler, “Submarine Wall,” sited in Galveston Bay (U.S. 325,127).

5d: Peter Voorhis, “Obstructing Ice in Rivers and Harbors,” sited in New York City (U.S. 63,968).

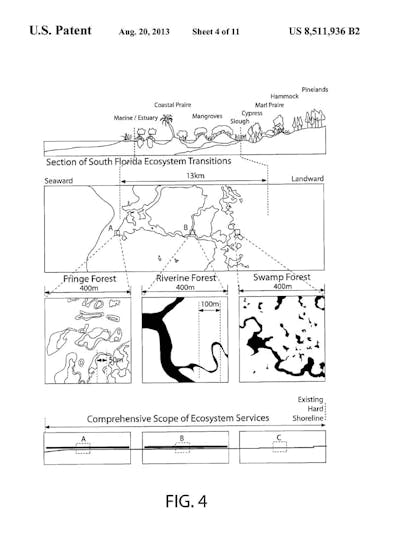

5e: Keith Van de Riet, Jason Vollen, and Anna Dyson, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, “Method and apparatus for coastline remediation, energy generation, and vegetation support,” sited in global mangrove ecosystems (U.S. 8,511,936).

Although patent cartographies usually lack the scale and graticule of conventional mapping, known locations are sometimes clearly demarcated with labels and identifiable boundaries. Not only can those places be recalled, known, or visited in the real world; they are also sites of technological innovation. As representations, the maps range in specificity from systems diagrams that situate an invention within a known location to detailed bathymetries that show the resultant geomorphology of a specific intervention. Examples include proposals for the removal of ice from New York Harbor and the East River, a passive dredge system for Galveston Bay, a hydroelectric plant for Niagara Falls that preserves scenery and produces power, and even current infrastructure/ecology hybrids designed to reinforce and cultivate mangrove ecosystems in Florida and around the world.10

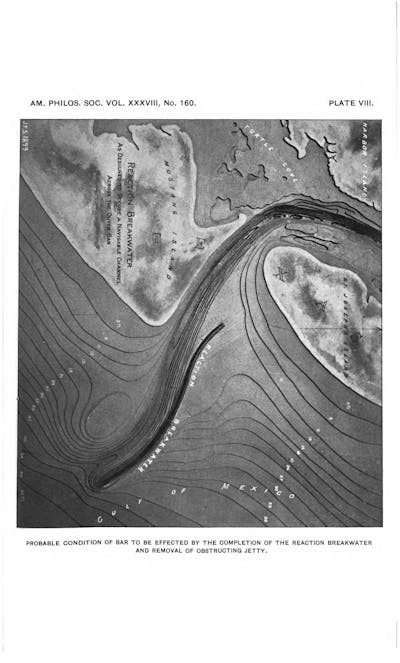

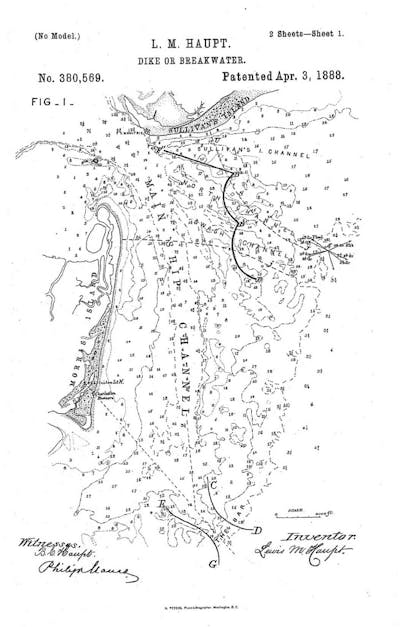

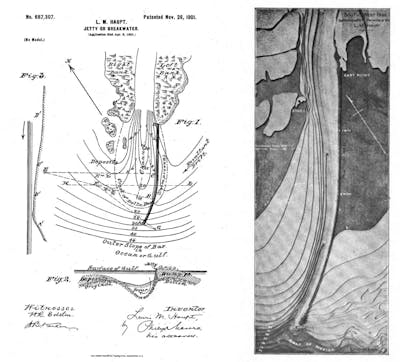

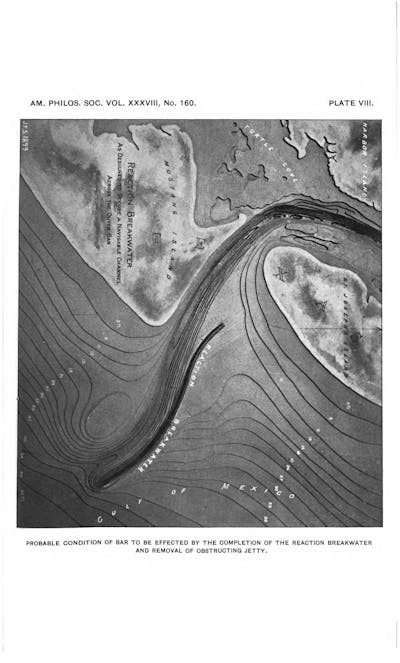

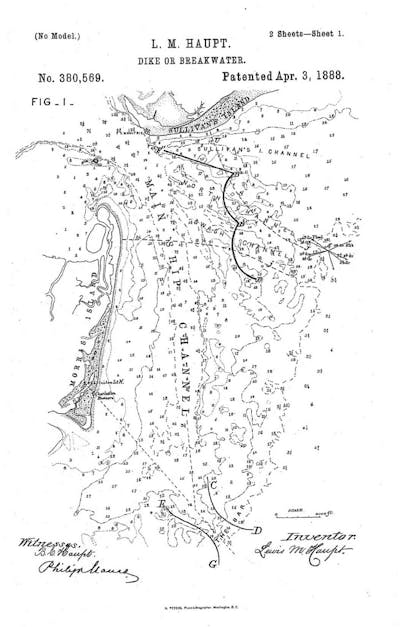

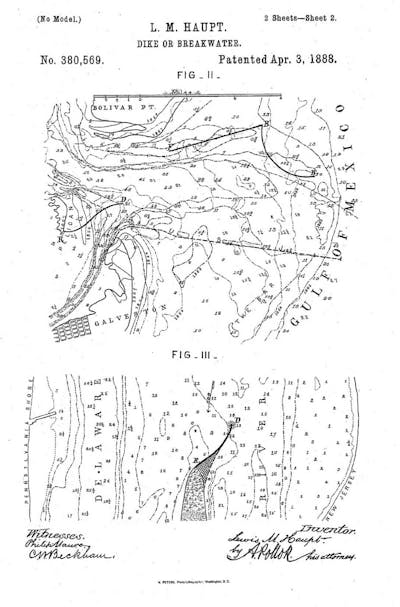

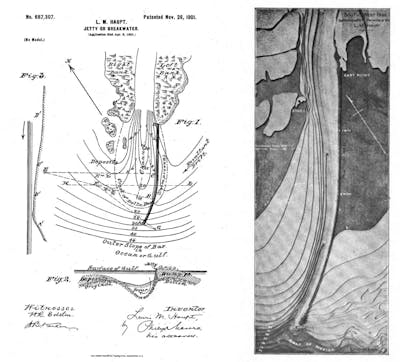

What is the relationship between patent cartographies and known geographical locations? Site specificity within patents raises important questions about the extents and jurisdiction of patent law, in addition to challenging commonly accepted models for innovation in complex environmental systems. Take, for example, the life work of Lewis M. Haupt (1844 – 1937), a professor of civil engineering at the University of Pennsylvania and, before that, a patent examiner at the USPTO.11 Haupt’s theories on the “Physical Phenomena of Harbor Entrances” earned him a Magellanic Premium award from the American Philosophical Society in 1887, and, on the same day that he accepted that award, he was granted a U.S. Patent for a “Dike or Breakwater,” which linked his design theories to known environmental conditions and specific locations.12 Following in the footsteps of Eads and others advancing American infrastructure through public/private partnerships, the “Reaction Breakwater,” as Haupt’s invention was popularly known, was to be prototyped at Aransas Pass, Texas, by the Reaction Breakwater Company using the specification of his patent.

Figures 6a‑c: Lewis M. Haupt’s patent for the “reaction breakwater,” sited in Texas, Delaware/New Jersey, South Carolina, and partially prototyped at Aransas Pass, Texas. Professor Haupt received a Magellanic Award from the American Philosophical Society and a patent for a “Dike and Breakwater” from the United States Patent and Trademark Office (U.S. 380,569). Pictures of the design models show the before and after conditions of Aransas Pass.

6a: Lewis M. Haupt, model for the “reaction breakwater” as partially prototyped at Aransas Pass, Texas. Image: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 38: 160 (October 1899): 139, plate VIII.

6b: Lewis M. Haupt, “Dike or Breakwater” (U.S. 380,569), sheet 1 of 2.

6c: Lewis M. Haupt, “Dike or Breakwater” (U.S. 380,569), sheet 2 of 2.

After a revision to the contract, however, the Federal Government ultimately awarded the bid for construction to another company, which intended to build the breakwater per Haupt’s specifications. During this process, Haupt’s patent was assigned to the U.S. Government for use at Aransas Pass. In turn, the Secretary of War, responsible for overseeing improvements in rivers and harbors, dismissed Haupt’s research and patent as “purely theoretical,” insisting that all of his discoveries were “unconfirmed by experience, and contain nothing not already well known, and which has a useful application in the improvement of our harbors.“13 The War Department’s attempt to discredit Haupt’s invention also inadvertently cast doubts on the American Philosophical Society’s Magellanic Premium, which Haupt defended tirelessly in lectures to the Society and through publications.14 Haupt eventually petitioned Congress for payment for partial use of his patented invention, but only after the debacle called into question the role of patent innovation in civic and public works under the jurisdiction of the federal government.

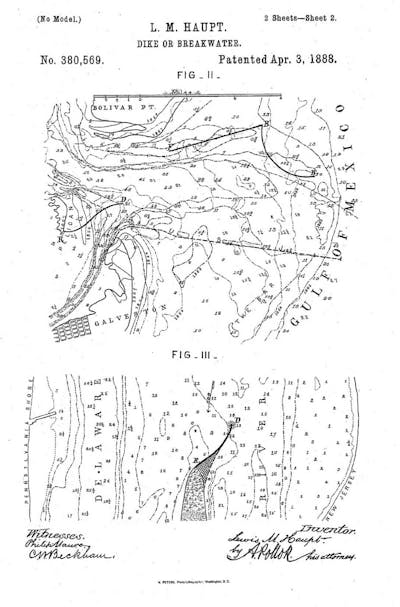

Accusations of patent infringement and the botched construction process resulted in a lawsuit between Haupt and the Secretary of War, in which ruling the jetty was declared property of the U.S. Government and, therefore, not subject to intellectual property infringement. Haupt’s difficulties proposing innovations for works under the jurisdiction of the federal government and the Army Corps of Engineers did not dissuade him from further explorations, and he continued to develop patent proposals for places such as the Southwest Pass on the Mississippi River, following in Eads’ footsteps of twenty-five years earlier at the South Pass.15

7: Lewis M. Haupt’s site-specific patent for a “Jetty or Breakwater” at the Southwest Pass of the Mississippi River (U.S. 687,307) resulted from an adaptation of the “reaction breakwater” for the specific conditions of Mississippi. The design models show the resultant fluvial geomorphology of the patented design. Image: Lewis M. Haupt, "History of the Reaction Breakwater at Aransas Pass, Texas," Journal of the Franklin Institute 165: 2 (February 1908): 92, figure 5

In the later years of Haupt’s career, he also consulted on the need for innovation in infrastructure and helped formulate a critique of new patent law that attempted to suppress patent innovation in civic works.16 Interestingly, by 1920, the federal government was involved in fifteen million dollars of patent infringement lawsuits, and several million dollars of suits related to improvements in rivers and harbors.17

Irrespective of the shifting landscapes of patent law, the ever expanding role of government in large-scale engineering works, or the lack of clear financial incentives for works that preclude commodification, inventors and innovators attempted to reinvent the built environment and natural systems using the legal and institutional mechanisms of the patent. Today, this record provides an inductive view of environmental design thinking and a fruitful repository for future innovation studies. New tools may be needed to link patent innovation to place and the unique conditions, durations, and scales of complex environmental systems. For example, maps and other cartographic forms of representation are not the only indicators of site-specificity in the patent archive. Known geographic locations are also sometimes described in textual claims and descriptions, even though the associated patent diagrams and drawings remain siteless. Mentions of known locations are especially easy to overlook. More than 9 million patents have been granted to date in the United States, and each of those contains many words — even into the tens of thousands — making textual searches for known locations difficult. Nevertheless, even within surficial readings of historical patent texts, we find evocative environmental design proposals, such as a passive levee construction system for California’s Central Valley meant to balance source/sink sediment budgets during periods of gold rush, a flood control system along the southern reaches of the Mississippi River prior to the great floods of 1927, a method of constructing navigable channels at the Heads of Passes that potentially stabilizes hectares of deltaic landscape, and others to be discovered.

Redrawing the Places of Intellectual Property

When thinking of patents, one typically pictures some type of thing. Historical interrelations among manufacturing, industrialization, and patents has resulted in a distinct “thingliness” (think cotton gins, plows, tie holders, automobiles, toasters, etc.), though business models, construction processes, chemical formulas, cartographic systems, methods of manufacturing, and other “non-things” also have a long history of patent innovation.18 Things and non-things alike may be granted the protection of a utility patent, given that the nature of their claims is non-obvious, innovative, and discloses the function and configuration of a specific “art.” The hybridizing of geographical studies with patent innovation studies suggests a scale, scope, and orientation for intellectual property claims that verge of the infrastructural, ecological, and environmental. Landscapes are not things, cities are not things, and coastal zones are not things, yet each is subject to the iterative and often deterministic forces of human ingenuity.

In the following texts and images, I investigate site-specific patents that function at landscape and regional scales but with drawings and diagrams that are siteless and scaleless. We know of each patent’s site specificity through the inclusion of geographical terminology and reference to specific places and regions within the patent text, but the scale and impact of the proposed intervention remains open to interpretation. In one drawing per patent, I adapt claims and technical specifications to the geographical location described in the text, synthesizing historical research and maps with the “new” innovation disclosed in the patent. The texts and images presented here are, in their simplest form, ruminations on the intersections of place and intellectual property. They provide geographical context to patents that may have radically altered the American landscape, transcending the object-oriented history of patents to suggest a new hybrid at the intersection of technology and environmental geography of innovation.

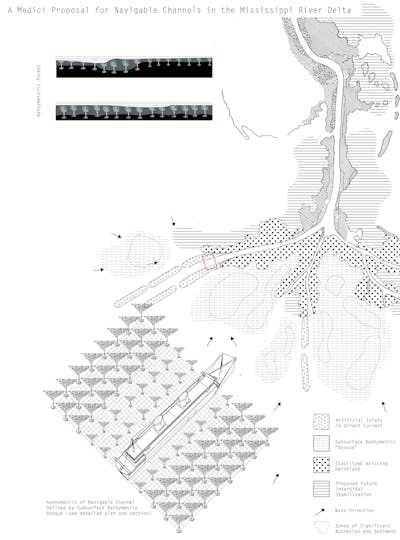

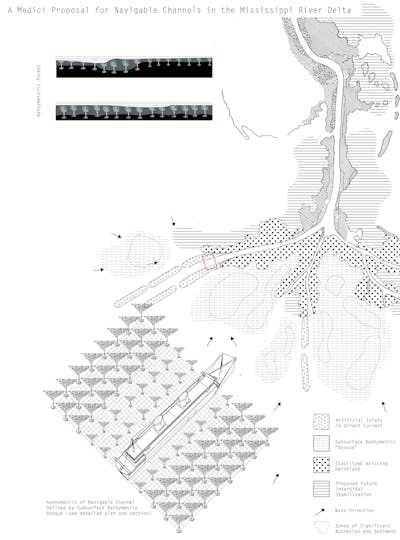

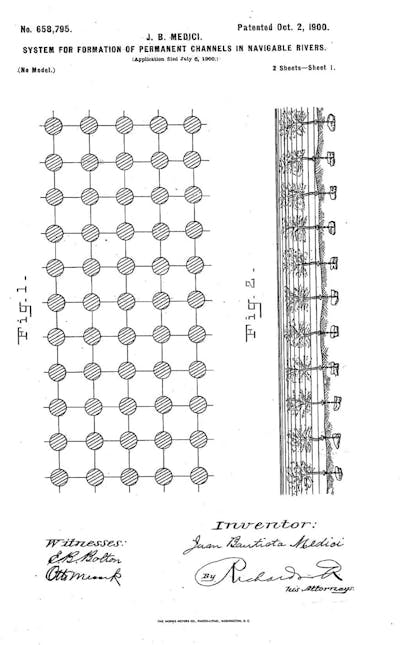

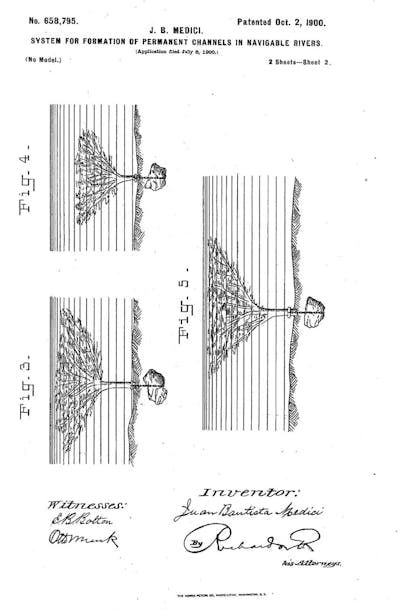

A Medici Proposal for the Mississippi – US Patent 658,795

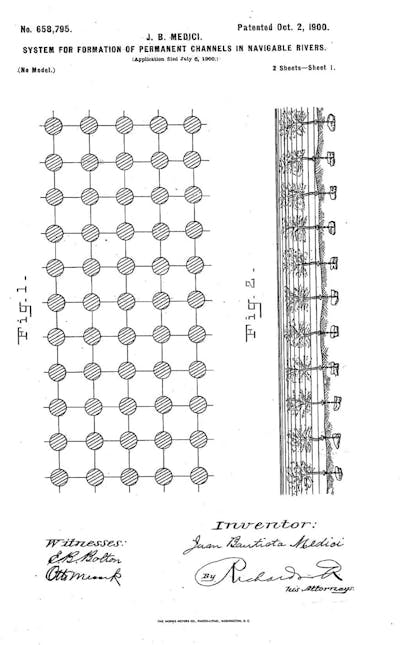

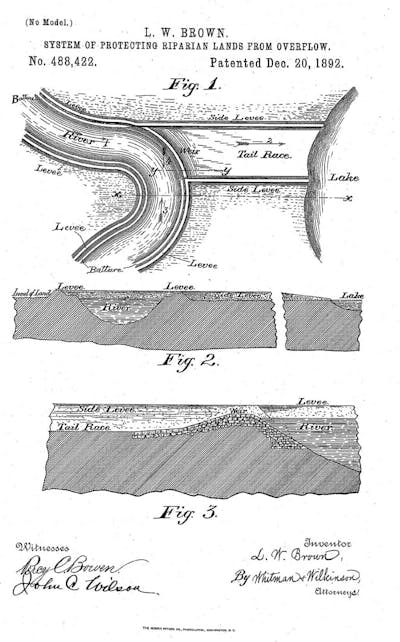

Juan Bautista Medici was born in Piedmont, Italy, in 1843 and died in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1903. While residing in Italy, he worked as an engineer on domestic railroad projects and the potable water network of Montevideo, Uruguay. After emigrating to Argentina in 1870, Medici became involved in the detailed survey of Buenos Aires. Later, together with the Argentine engineer Lavalle, he graded 175,000 square kilometers of the province of Buenos Aires. The latter was followed by the construction of an extensive network of channels to drain the area and the addition of two navigable channels. This project was awarded a gold medal at the Esposizione Italo-Americana in Genoa (1892).19 During his illustrious career in Argentina, Medici was also involved in the layout, planning, waterworks, and construction of the capital of the province of Buenos Aires, La Plata.20 At 57 years old, and after a lifetime’s work in civil and hydrologic engineering, Medici submited his patent to the USPTO with the intention of reconfiguring the delta of the Mississippi River.21 Medici intended for his invention to be a direct technological retort, or innovation, following Eads’ Jetties at the South Pass of the Mississippi. Medici claimed:

The system of jetties or artificial islets formed of brush and earth employed, for example, in the delta of the Mississippi [referring to Eads’ Jetties] has fallen short of desired results, owing to the rigid nature of the resistance thus offered to the tremendous for of wave and current, before which force such rigid bodies must eventually give way. I have therefore sought to overcome the defects of such systems in the manner which I will now proceed to describe.

Medici’s patent involves the anchoring of a subsurface “forest” or “orchard” of large, cut trees with variable depths relative to the surface to guide flowing water and capture sediment. The field or matrix of vertical trunks and branched canopy would alter the speed and direction of water by establishing a new bathymetry of tree canopies that define channels, islets, and bars at the river delta. The system invites us to imagine a vast deltaic landscape constructed on principles observed in naturally dynamic deltaic landscapes, yet designed to meet human necessity for navigation. Medici’s proposed structure is expansive, potentially extending for miles, and would function at a scale commensurate with the deltas of large rivers. When compared with conventional technologies for engineering of navigable channels, such as jetties and breakwaters, Medici’s proposal neglects the singular object and, therefore, precludes object-oriented description, evoking instead various conditions found in nature or other large-scale productive landscapes such as field, forest, orchard, plain, island, field, delta, etc.

8a: Richard L. Hindle, “A Medici Proposal for Navigable Channels in the Mississippi River Delta” (2015/2016), referencing Juan Bautista Medici, “System for Formation of Permanent Channels in Navigable Rivers” (U.S. 658,795). The drawing adapts the specifications of Medici’s patent to the Mississippi’s Heads of Passes, showing navigable channels created by artificial islets, and stabilization of the delta through a subsurface bathymetric bosque.

8b: Juan Bautista Medici, “System for Formation of Permanent Channels in Navigable Rivers” (U.S. 658,795), sheet 1 of 2.

8c: Juan Bautista Medici, “System for Formation of Permanent Channels in Navigable Rivers” (U.S. 658,795), sheet 2 of 2.

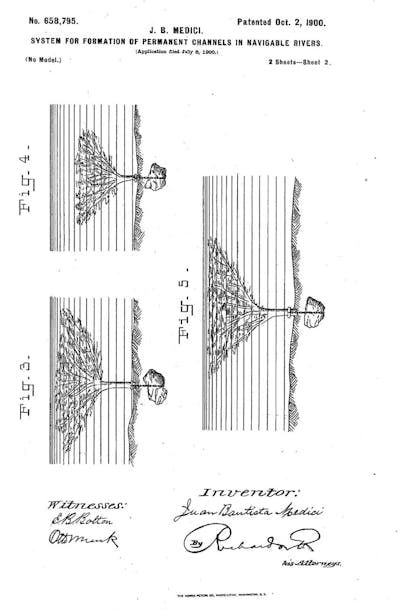

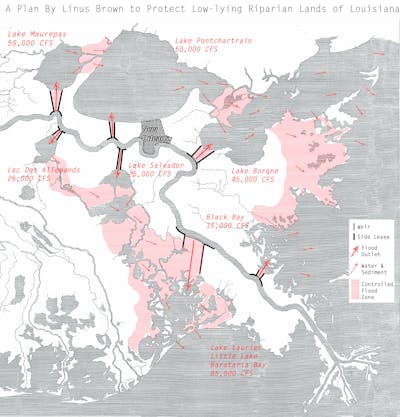

Protecting Southern Louisiana’s Riparian Lands from Overflow – US Patent 488,422

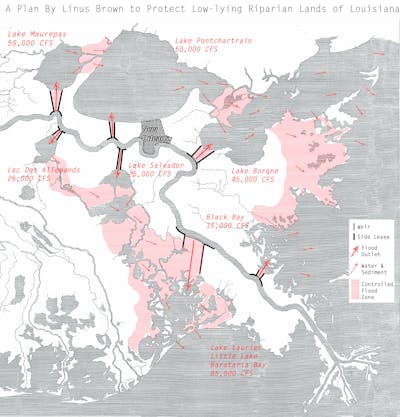

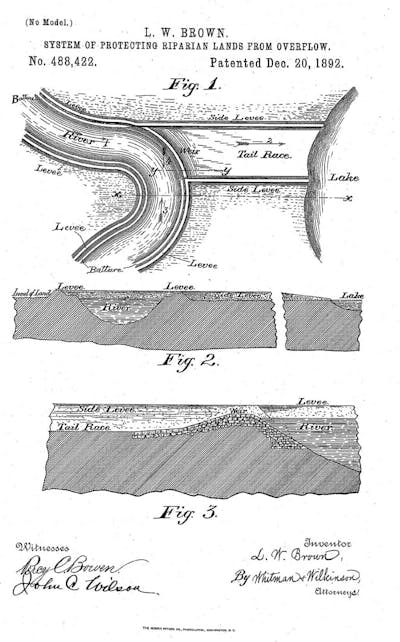

Linus Weed Brown (1856−1910) was appointed assistant engineer of the City of New Orleans in 1885 and chief engineer in 1892. In those capacities, he completed detailed topographical surveys of the city, including studies of precipitation and run-off and detailed proposals for a drainage system.22 He later published a booklet summarizing the complex engineering works undertaken while he was a city engineer.23 Brown’s work on the drainage of New Orleans necessitated a comprehensive understanding of the Mississippi River levee system and the topography of the region. In 1892, just as he was appointed chief engineer for New Orleans, he was also granted a patent for a “System of Protecting Riparian Lands from Overflow,” which advanced the art of flood management by using outlets or “waste weirs” along the lower Mississippi. Located at precise flood elevations along the river’s course, the weirs would carry floodwater to adjacent lakes, where it would be distributed naturally through the vast deltaic network of bayous and channels draining ultimately into the gulf. Brown suggested that his system be implemented at Lake Brogne and Lake Maurepas, and at as many river bends as necessary to distribute floodwaters effectively. Although the primary purpose of Brown’s invention was to protect low-lying lands from overflow, it might also have facilitated sediment recharge in a delta starved by levees. Boosters of the “levees only” policy ultimately discredited alternate proposals, including designed outlets such as Brown’s, even though critics knew that a levees only solution to flood control would to contribute to the collapse and subsidence of the Mississippi River Delta.24 The weir plan was never implemented during the legal period of Brown’s patent. Interestingly, the Bonnet Carre Spillway, which employs a weir system to divert water to Lake Pontchartrain, was constructed after the devastating floods of 1927 submerged thousands of acres of land. That event occurred 39 years after Brown’s patent was granted and a decade after expert witnesses argued before Congress in favor of waste weirs similar to those Brown proposed for the Mississippi.25

9a: Richard L. Hindle, “A Plan by Linus Brown to Protect Low-lying Riparian Lands of Louisiana” (2015/2016), referencing Linus Weed Brown, “System of Protecting Riparian Lands from Overflow” (U.S. 488,422). The drawing sites Brown’s patent at bends of the Mississippi River to facilitate in the discharge of floodwater to natural lakes and bayous in the delta upstream and downstream of New Orleans. The weirs and side-levees would alleviate rising floodwaters incrementally and allow for the recharge of sediment back into the deltaic landscape during periods of freshet.

9b: Linus Weed Brown, “System of Protecting Riparian Lands from Overflow” (U.S. 488,422).

Source/Sink Levee formation in California Delta – US Patent 235,967

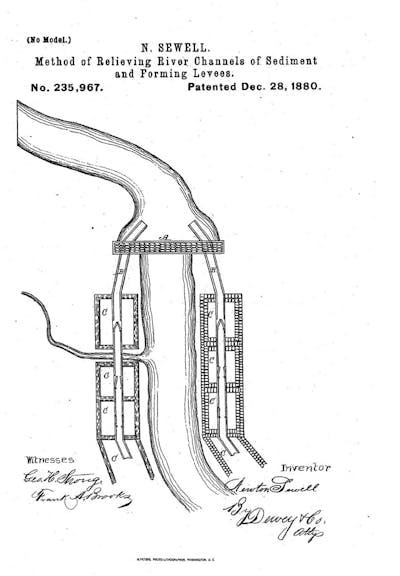

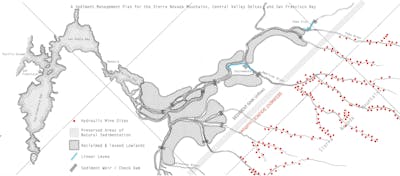

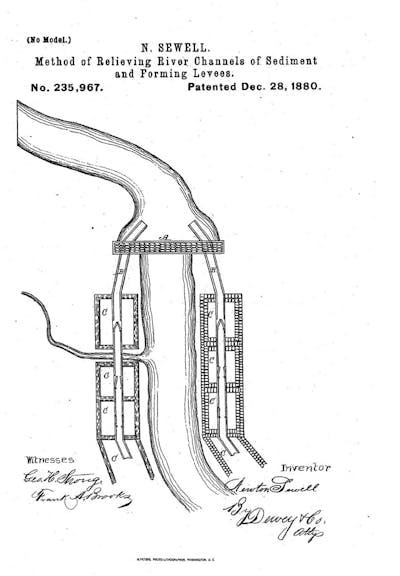

On December 28, 1880, Newton Sewell (1821 – 1902), a county assessor and landowner in Yuba, California, was granted U.S. Patent 235,967, which describes a passive hydraulic method for levee formation through the construction of check dams within sediment-laden rivers. The dams would divert accumulated sediment to a series of settling enclosures that in turn would become a levee. Sewell’s patent for a “Method of Relieving River-Channels of Sediment and Forming Levees” utilizes the energy of rivers, local topography, and river sediment of the gold rush to build levees in California’s Central Valley. The design is topographical in nature, correlating the slopes of rivers, dam sequences, and sediment enclosures to the locations of levees. Sewell’s invention was conceived in the later years of hydraulic dredging practices for gold mining in the upper reaches and tributaries to the Sacramento and San Joaquin Delta (aka the California Delta) — a mining process that almost choked the delta and San Francisco Bay with sediment. During this period, an estimated 300 million cubic meters of sediment were moved by rivers and creeks from the Sierra Nevada Mountains into the Central Valley and San Francisco Bay — enough material to cover 380 square miles at a depth of one foot. Sewell’s design is noteworthy not only for its engineering of the intrinsic fluvial processes of rivers and for linking levee formation to topographical change in river systems, but also for its mastery of regional source-sink sediment budgets in river systems by utilizing the sediment generated upstream, in the distant reaches of the Sierra Nevada Mountains to build levees downstream in the productive alluvial plains of the valley. Sewell also suggested that the system might be used to “reclaim,” or raise, low lying areas through the addition of sediment — an interesting and farsighted proposal given the massive subsidence in the delta today resulting from extensive levee construction, agriculture, and oxidation of rich organic soils. The process is quite simple, utilizing a series of low-crested check-dams to raise the level of water and divert sediment-laden water into settling enclosures, allowing for levee formation at an increased height relative to the original elevation of the river. Once the levee has formed and the dam is removed, the river elevation recedes to normal and the levee remains elevated. When envisioned serially along the reaches of a river system, a mosaic of leveed lands can be envisioned, similar to the natural bars and highlands formed intrinsically by migrating rivers. Importantly, the system was developed for implementation along the rivers of central California, between the gold rich lands of the Sierra Nevada and agriculturally productive lands of the California Delta, a statewide sediment management plan disclosed in patent.

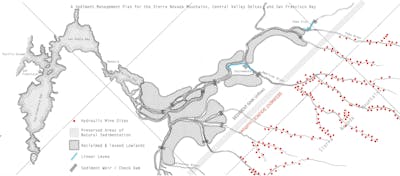

10a: Richard L. Hindle, “A Sediment Management Plan for the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Central Valley Deltas, and San Franciso Bay” (2015/2016), referencing Newton Sewell, “Method of Relieving River Channels of Sediment” (U.S. 235,967). The drawing envisions the potential scale and reach of Newton Sewell’s invention, adapting the patent to the conditions of the Sierra Nevada mountains and the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta during the California Gold Rush, when millions of cubic feet of sediment were displaced by hydraulic mining. The drawing and patent explore methods for the creation of a regional sediment management plan and levee system balancing source/sink sediment budgets for vast river systems.

10b: Newton Sewell, “Method of Relieving River Channels of Sediment” (U.S. 235,967).

Conclusion

Patents have indirectly mirrored and defined the built environment since the Italian Renaissance, when the first true patent was issued to the architect Brunelleschi. As the founders of American Democracy pondered innovation and patents centuries later, they created a system to promote invention, limit monopolies, and expand the public domain of shared intellectual property, while simultaneously building a new nation. The potential for environmental transformation implicit in new technologies was well understood by Jefferson and others, yet the future permutations of technology and environment remained indeterminate and unforeseen. Importantly, the authors of the Constitution (1787) and the subsequent Patent Act of 1790 put few limits on what may be patented,26 which liberated the creative spirit of a citizenry to evolve all sectors of “the arts,” including the lesser-known environmental arts. Many important questions are raised by the curious reciprocity between patents and the built environment, including the potential for innovative new ideas to transform places. The anomaly of site-specificity within patents is only one rhetorical and historical framework through which to explore the environmental arts. Within this narrow sampling, or innovation study, we can trace a lineage from Thomas Paine’s bridges for the Hudson and Schuylkill Rivers, to the unrealized deltaic innovations proposed by Juan Bautista Medici at the Mississippi, to the built works of Lewis M. Haupt. They are linked not only by their integration of known geographical locations with specific technological innovation, but also through the precedent they establish for innovation in the environmental arts — work as relevant and formative today as it has been for centuries.

Review

By Diana Balmori

Given the contingency of landscape, it is shocking to see patents proposing environmental solutions to large geographies — deserts, rivers, coastlines — with no indication of place whatsoever, in either drawing or text. Richard Hindle’s account of patents without place offers a rare look — at once revealing and surprising — at the patent process in relation to landscape. Hindle does include examples where location is mentioned in the text or indicated on a map, but one catches on quickly that leaving place out supports a patent’s claim to universal applicability.

Even more shocking is just that fact: that patents would deal with large geographies and propose environmental solutions. One imagines a patent to be an object that is a new invention, a machine of some kind, not a large-scale land management strategy formulated in singular circumstances.

For readers not familiar with these patents and their significance for landscape, two further observations warrant consideration. The first is that inventive responses to complex environmental problems with which we are wrestling today began appearing in patents two centuries ago. For example, James Buchannan Eads — the designer and builder of the Eads Bridge in St. Louis, among other important works — offered solutions for the management of the Mississippi River. A most creative engineer, Eads engaged in a long battle with civil engineer Andrew A. Humphreys and the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) about the treatment of the Mississippi and proposed solutions more in line with present-day environmental understanding than the levees-only approach that the USACE adopted in winning that battle. Interesting alternatives are described in two of the patents illustrated by Hindle: Eads and James Andrews’s “Mattrass for Forming Embankment” (U.S. 170,832) and Linus Brown’s “System of Protecting Riparian Lands from Overflow” (U.S. 488,422). In the latter of those, Mississippi flood waters are deviated to low-lying terrains and marshes, restoring them with the silt needed to maintain their ecosystems. This is closely related to Eads’ proposal of cutoffs in his long battle with Humphreys.

The second observation is that landscape-based patents with a location are more convincing and understandable, at least to an engineer, environmentalist, or landscape architect, than are those without. But to those reading patent applications — not engineers with environmental training, one imagines — location could not have counted for much, at least then. The spread of environmental knowledge and public airing of the problems with past solutions make the task of the patent office a more informed one today.

In the end, a question hangs in the air as to the validity of patents torn from the sites that elicited them. Contingency and place are central to landscape: “A landscape, like a moment, never happens twice. This lack of fixity is landscape’s asset.”{endnote-27} With that in mind, Hindle’s “Patent and Place” calls for a new look at patents — both old and new — proposing environmental solutions for large territories.

Notes

1

See Frank D. Prager, “Brunelleschi’s Patent,” Journal of the Patent Office Society 28 (February 1946): 109 – 135.

2

Ibid., 109.

3

For a discussion of eidetic images and landscape representation, see James Corner, “Eidetic Operations and New Landscapes,” in Recovering Landscape: Essays in Contemporary Landscape Architecture, ed. James Corner (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999): 153 – 169.

4

See Barry Bergdoll, Peter Christensen, and Ron Broadhurst, Home Delivery: Fabricating the Modern Dwelling (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 2008).

5

See Richard L. Hindle, “A Vertical Garden: Origins of the Vegetation-Bearing Architectonic Structure and System (1938),” Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes 32: 2 (2012): 99 – 110.

6

See Elijah Huge, “Saving the City,” Praxis 10 (2010): 120 – 127; Richard L. Hindle, “Levees That Might Have Been,” Places (May 2015)

7

Kendall S. Dood and National Archives and Records Administration, Patent Drawings (Washington, DC: Published for the National Archives and Records Administration by the National Archives Trust Fund Board, 1986). N.B.: Models were only required by law until 1870, though the Patent Office accepted models with applications until 1880.

8

E. L. Corthell, A History of the Jetties at the Mouth of the Mississippi River (New York, NY: J. Wiley and Sons, 1880).

9

Thomas Paine, Daniel Edwin Wheeler, and Thomas Clio Rickman, The Life and Writings of Thomas Paine: Containing a Biography, vol. 10: Essays, Letters, Poems (New York, NY: Vincent Parke and Company, 1908), 238 – 239

10

See Peter Voorhis, “Improved Method of Obstructing Ice in Rivers and Harbors,” US Patent 63,968, published April 16, 1867; Daniel Spangler, “Submarine Wall,” US Patent 325,127, published August 25, 1885; Christian J. Zeitinger, “Device for Utilizing the Water-Power of Falls,” US Patent 442,000, published December 2, 1890.

11

Leland M. Williamson, Richard A. Foley, Henry H. Colclazer, Louis N. Megargee, Jay H. Mowbray, and Will. R. Antisdel, Prominent and Progressive Pennsylvanians of the Nineteenth Century (Philadelphia, PA: Record Pub. Co., 1898).

12

Lewis M. Haupt, “Dike or Breakwater,” US Patent 380,569, published April 3, 1888.

13

Haupt, “History of the Reaction Breakwater at Aransas Pass, Texas,” Journal of the Franklin Institute 165: 2 (1908): 81 – 97: 82.

14

See American Society of Civil Engineers, Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers (1905): 435 – 451

15

Haupt, “Jetty or Breakwater,” US Patent 687,307, published November 26, 1901.

16

United States Congress House Committee on Patents and William Allen Oldfield, Oldfield Revision and Codification of the Patent Statutes: Hearing Before the Committee on Patents, House of Representatives, on H. R. 23417 (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1912).

17

See United States Department of Justice, Annual Report of the Attorney General of the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1917), 433; The Washington Law Reporter, ed. Richard A. Ford (Washington, DC: [The Law Reporter Printing Co./Powell and Ginck], 1909): 79 – 80; and Illinois Attorney General’s Office, Biennial Report and Opinions of the Attorney General of the State of Illinois: 1914 (Springfield, IL: State Printers, 1915): 1328

18

See Gregory A. Stobbs, Business Method Patents (New York, NY: Aspen Law & Business, 2002).

19

Dionisio Petriella, Los italianos en la historia del progreso argentino (Buenos Aires, Argentina: Asociación Dante Alighieri, 1985), 267 – 268.

20

Oficina de Estadística General, Ministerio de Gobierno, Argentina, Anuario Estadístico de La Provincia de Buenos Aires, ed. Emilio R. Coni (Buenos Aires, Argentina: Imprenta y Fundicion de Tipos La República, 1883), 2 vols.

21

Juan Bautista Medici, “System for Formation of Permanent Channels in Navigable Rivers” US Patent 658,795, published October 2, 1900.

22

See American Society of Civil Engineers, Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers (1910): 470 – 472.

23

Linus Weed Brown, Illustrations of Drainage & Harbor Work: City of New Orleans (New Orleans, LA: T. Fitzwilliam & Company, 1900).

24

Elmer Lawrence Corthell, “The Delta of the Mississippi River,” National Geographic Magazine 7: 12 (December 1897): 351 – 354.

25

United States Congress, House Committee on Floods, The Mississippi River Floods: Hearings Before the Committee on Flood Control, House of Representatives, Sixty-Fourth Congress, First Session, on Floods of the Lower Mississippi River, March 8,9,10,13,14, and 15, 1916 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1916.)

26

Among the exceptions were laws of nature, philosophies, and universal mathematical equations.

- Tags

- placetechnologyhistory

Biographies

Richard L. Hindle is an assistant professor of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning at the University of California, Berkeley, where he teaches courses in ecological technology and planting design as well as site design studios. Hindle’s research focuses on technology in the garden and landscape with an emphasis on material processes, innovation, and patents. His current work explores innovation in landscape-related technologies across a range of scales, from large-scale mappings of riverine and coastal patents to detailed historical studies on the antecedents of vegetated architectural systems. Hindle’s writings have appeared in Landscape Architecture Magazine, Places, and Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes. In 2012, he received a Graham Foundation Award for the reconstruction of Stanley White’s “Vegetation-Bearing Architectonic Structure and System” (patented 1938). As a consultant and designer, Hindle specializes in the design of advanced horticultural and building systems, from green roofs and facades to large-scale urban landscapes. He has worked with such prominent firms as Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, Steven Holl Architects, Rios Clementi Hale Studios, and Atelier Jean Nouvel. Hindle holds a B.S. in Horticulture from Cornell University and a MLA from the Rhode Island School of Design. Email: rlhindle@berkeley.edu

Diana Balmori is founding principal of Balmori Associates, a landscape and urban design practice recognized worldwide for designing sustainable infrastructures that serve as an interface between landscape and architecture. In 2006, she created BAL/LABs within Balmori Associates to push further the boundaries of architecture, art, and engineering. Balmori is an active voice in national policy and decision-making pertinent to landscape design, architecture, and urban planning. She has served as a member of the US Commission of Fine Arts, a Senior Fellow of Garden and Landscape Studies at Dumbarton Oaks, a board member at the Van Alen Institute, and chair of the Civic Alliance World Trade Center Memorial Committee, among other distinguished appointments. She is the author of numerous books — most recently, Drawing and Reinventing Landscape (2014), Groundwork: Between Landscape and Architecture, with architect Joel Sanders (2011), and A Landscape Manifesto (2010). Writings by and about Balmori have appeared in a wide range of media, including Dwell, Monocle, El País, PBS, Design Observer, and Utne Reader, which named her one of fifty “Visionaries Who Are Changing Your World” (2009). In 2013, she was ranked #3 on Fast Company’s list of “The 100 Most Creative People in Business” and one of ten “AD Innovators” by Architectural Digest. Balmori studied architecture at the University of Tucumán, Argentina, landscape design at Radcliffe College, and urban history at UCLA, where she was awarded at Ph.D. with highest honors. Since 1993, she has been a Critic at Yale University in both the School of Architecture and the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.