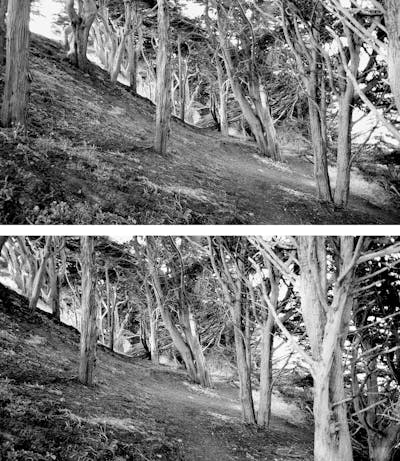

Rainy Sea is a small piece of land located in the middle of a large river separating the United States and Canada. Historical accounts of the island are so varied that they appear to refer to entirely different places, and when different maps of the island are overlaid, the shapes of their contours seldom agree. Despite its small size, Rainy Sea has played an important role in defining the region by providing an almost comic caricature of the many masquerades, manipulations, and political deceptions that have characterized the area’s unique history. From a distance, Rainy Sea appears abandoned, overgrown with trees and resembles a wilderness.

Though it is located near a large city, Rainy Sea feels isolated and far away. Throughout its history, the island has been repeatedly discovered, built up, torn down and abandoned, and it is currently littered with the remains of numerous buildings including a prison, an aquarium, a bunker, and a series of small decaying factories. Along with the forests and random wildlife that have overtaken the fragments of remaining structures, quarries and a cemetery are the vestiges of an amusement park built many years ago that no one has bothered to remove. Stacks of rusted scaffolding and fallen statues once used to decorate the park’s ticket stands and concessions now line the crumbling edges of empty swimming pools and dissolving beachfronts, and concrete bunkers once covered by earth stand exposed atop eroding hillsides. The arrangements of roads and trees, lacking the presence of the buildings that formerly justified them, suggest a strange topography of non-destinations and vacant centers.

The island is a geographical conundrum, a bizarre assemblage of familiar things disconnected from their original contexts and inserted back into circumstances to which they no longer relate. More curious than the array of once-purposeful constructions rendered useless is the way they conjoin, fall apart and entice one to draw connections among them, despite the futility of doing so with any certainty. For those who have grown up in the nearby city, the island is more of an idea about a destination than a place they would ever go, something to be seen through rather than thought about. The apparent invisibility of Rainy Sea is what allows it to hide what happens there. From military bases and secret prisons to storage facilities and illegal dumpsites, the island has been a tool for “disappearing” the functions it provides.

//

The sound of the small plane’s engine was the only indication of its presence as it flew through the early morning fog. Paul stared into a cloudy window while an overweight steward wheeled a service cart down the aisle along mostly empty seats. As the steward neared the back of the plane, Paul imagined the aircraft’s overloaded tail pushing the plane’s nose involuntarily upward — and was reminded of a painting he had seen of a tortured saint looking up to heaven as a swarm of demons carried his body off to hell.

Paul had wanted to stay on the island for the sake of his sisters but ran away to protect himself. He judged himself a failure, first for having abandoned them and later for continuing to doubt the rightness of his decision. As his sense of inadequacy grew, so, too, did his need to invent the possibility of a different future for himself. He visualized the embryo of another “Paul” in the form of a minute sub-fraction of himself he called the “precious pearl.” The pearl fed upon his anxieties like a friendly parasite and converted them into growth food for the second body that, he hoped, would one day replace him. As he awaited the insurrection of the growing pearl, the old Paul rehearsed dialog for the Nuremberg-like war trials in which the unsupportive parts of his former self would be tried and hung.

Returning to the island now after so many years, Paul realized that his faith in the pearl had waned, and the image he had clung to of it glowing deep inside had faded. And though the idea of a better Paul growing out of the person he was no longer inspired him, the question remained as to whether his sense of something missing was a bodily sensation of the unoccupied area allocated for the fully grown pearl or the idea of an irreparable hole with which the story of the precious-pearl had infected his otherwise fulfill-able life.

//

I grew up in a single house within two families. My parents each lived there with my twin sisters, Agnes and Paula, and me, but on different days of the week. My mother was there from Sunday to Wednesday. She was moody and demanding and managed to convince us that her needs were always more important than ours. My memories of my father are less distinct. He was with us Thursday to Saturday, seldom spoke and drifted aimlessly through the house like a ghost. My mother obliterated us with her presence, and my father hardly appeared at all. The two of them rotated in and out of the house while we shuttled between their lives.

As children, my sisters and I each had some identifiable problem with vision. I wore bifocal glasses that quadrupled my view, and Agnes had an eye patch that cut hers in half. Paula had astigmatism in her left eye that caused her sight to double and blur. The eye doctor told me that one of my eyes was lazy — it didn’t want to do its job, drifted inward and left its partner to do all of the work. I liked the idea that there was confusion within my effort to see and politics among my parts. I had to wear thick glasses that made a horizontal line across my eyes where the seams of the differing lenses met. It was strange to me that the intersection of transparent things would produce visible edges. My glasses were frequently dirty, though I seldom noticed until I was reminded by others to clean them.

//

Paul gasped in his seat as the small dot came into view through the tiny window and then grew into an island as the plane descended. If he had known the night before that he would be on a flight back to Rainy Sea the next day, he would have found a way to avoid it, but there he was returning to a place he wanted nothing more than to forget. As the wheels of the plane touched down, racing Paul towards his own distant past, the edges of the island reached up around him like a rising abyss. He rushed through the airport, kept his head down, and did what he could to block out the familiarity of the place. He renewed self-promises to leave the following day and struggled against his body’s efforts to re-root itself in the place from which it had so long ago been extracted. The image of a locomotive speeding towards disaster appeared in Paul’s head like The Little Engine That Could—but in place of the reassuring mantra of “I think I can, I think I can” he recalled from the book, he heard “fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck.”

//

My mother was the captain of a ferryboat that crossed back and forth between the island and the nearby city. She worked long hours that required us to ride along on the boat whenever we wanted to spend time with her. The highlights of these trips were the conversations we had about river navigation. I was fascinated to discover that the negotiation of local waterways had nothing to do with what one saw with one’s eyes and everything to do with knowledge of the unseen shape of the river bottom below.

My father was a librarian who was more interested in books than life. No matter where he was, he was reading. He walled himself away in stories to avoid dealing with the world. Over and over, I tried to talk to him by telling him things about my life as though I was a character in one of his favorite books, switching in and out of different voices to disguise my need for his attention in the perspective of different literary characters. “It’s so BRIGHT in here,” I would shout as the Invisible Man. “Why can’t you SEE me?”

//

Paul drove off in a cab without telling the driver where to go. When the phone had awoken him the night before, a man told him that one of his sisters was in the hospital and the other had disappeared. The man asked if Paul knew where a mysterious suitcase that his sister had asked for was and insisted that he come to the island as soon as possible. As the taxi sped forward, Paul considered options: he could go to Paula, look for Agnes, or visit the house where he had grown up and Paula still lived. Sitting in the seat not deciding, he erased everything he saw by re-describing it to himself: “That’s not the place where anything I can remember ever happened.”

He thought about the suitcase his mother had held against her chest every day as she rocked on the edge of the couch. The impression she left on the cushion remained for many years after her death and distracted him from ever wondering about the suitcase — though, thinking back, Paul wondered why he hadn’t been more curious. As the taxi turned suddenly to avoid an exposed manhole, one of its wheels dropped into it. The driver accelerated to free the spinning wheel as Paul lurched into the back of his seat, hearing, but not responding to, the driver’s demand that he get out of the car. With the sound of metal grinding against pavement, Paul looked up to see a sailboat passing on a trailer, reminding him of the submerged dry dock where they kept his mother’s ferry after the crash.

//

Our house stood between the edges of a forest and the river on the north end of Rainy Sea. Its windows were arranged in a way that, looking out, one had the impression of being in a large unmoving ship aimed permanently upstream. In my memory, the house is comprised of a series of fragmented hallways and incomplete rooms, each separated by inaccessible pockets of empty space and furnished in half-measures that made it difficult to know how to use the rooms despite the obvious purposes they were intended to serve. Thinking back, I have trouble reconciling what I know about the location of the house with what I remember seeing out of its windows. It is never clear to me if the house has shaped my memories, or if my memories have simply constructed a sympathetic landscape in which to appear.

Among the few pieces of advice my father ever gave me was “make yourself invisible and follow the rules.” My mother’s philosophy was the opposite — she thought rules were for other people and that we should do whatever we wanted, as long as we didn’t get in her way. I would have preferred the voice of a single all-knowing authority to the mutually exclusive set of life lessons I received from them, regardless of what it told me, or so I believed. Our house corroborated the madness of our conflicted parenting perfectly, composed as it was of a series of maze-like rooms that repeated and divided, concealing some areas and falsifying the limits of others. It had everything a house is supposed to have, but in the wrong number and arrangement, like a backwards head with two brains and a giant eye.

//

The tradition of making Rainy Sea appear different than it was extends back to the origin of its name. Similar to Iceland — a name devised by Icelanders to keep foreigners away by making it sound less appealing than it was — the Canadians named the island Rien Ici, French for “nothing here.” To the Americans, who would eventually steal it by changing Rien Ici into Rainy Sea, the mispronunciation was a way to alter its history. By calling the island “Canadian” during American Prohibition, Americans were able to sell alcohol legally, and when Canadians needed to dispose of the garbage they didn’t allow in their own country, the island became ”American.” When American businesses stood to gain more from Canadian tax laws than their own, they happily ceded the nationality of the place to the other, and when it benefited both countries to have a place to incarcerate political prisoners free of their respective laws, it was deemed a “no-man’s land.”

“Nothing Here” is an excerpt from Rainy Sea, a forthcoming book by Keith Mitnick. All images courtesy of the author.

Review

By Rod Barnett

At first we see rocks, river, forest, the familiar meta-objects of the natural world — large, heaving natural systems. They are presented as given, familiar to us. We walk and swim, fish, boat, sit and stare. But it’s not as if this über-landscape is that familiar. There’s a sense of edge, of not knowing, a pre-condition perhaps, for something beyond our ken that is about to happen. And then we begin to slide. Something inside reaches out to the world and something in the world stirs too. Now the trees are somehow dislodged from the forest and the rocks are etched with histories that are not just geological or oceanic. A passage opens up between my twin sisters and I drift through. The past opens up: my self-obsessed mother, my dumb bifocals that gave everything a horizon, that missing suitcase. Are they becoming one? Is this familiar landscape making me, or am I making it? Sky becomes sea and sea becomes sky. There is no longer a horizon. Maybe it is me. I open the suitcase and a swarm of demons flies out. They lift up through the trees, across the rocky coast and out into the gray zone above the waters. They have gone. So nothing is given. Nothing works. The island, the family… But dysfunctional systems awaken us to the rarity of the world, reveal aspects of the world that we forget are there, or overlook. They derail the assignment to which we sometimes feel our life has been dedicated — dedicated, that is, in the way that a book or a plaque is dedicated to someone (my sisters) or something (Rien Ici).

- Tags

- literatureplace

Biographies

Keith Mitnick is a founder of the design practice Mitnick Roddier and an associate professor of architecture at the University of Michigan, where he held the 2000 Sanders Fellowship in Architecture. Before joining the faculty at Michigan, Mitnick taught at the University of California, Berkeley. The work of Mitnick Roddier (formerly Mitnick Roddier Hicks) has been published and exhibited widely, with recognitions including the Young Architects Forum Award (Architectural League of New York), the Unbuilt Architecture Award (Boston Society of Architects), and the Architectural Record Design Vanguard Award. Mitnick’s independent writing and designs have appeared in Log, Praxis, and Harvard Design Magazine, and his research has been supported by two Graham Foundation grants and the Burnham Prize Fellowship to the American Academy in Rome. His first book, Artificial Light: A Narrative Inquiry into the Nature of Abstraction, Immediacy, and Other Architectural Fictions, was published by Princeton Architectural Press in 2008. Email: kmitnick@umich.edu

Rod Barnett is professor and chair of the Master of Landscape Architecture program at Washington University in St. Louis. He was previously chair of the graduate landscape architecture program at Auburn University and, before that, held similar positions at Unitec Institute of Technology in Auckland, New Zealand. Barnett earned a Ph.D. from the University of Auckland, where he researched the potential of nonlinear dynamical systems science to inform landscape architectural design and practice. As part of his studies, he developed a self-organizing approach to urban development called Artweb, a multidisciplinary design and planning strategy that focuses on marginalized and underutilized urban terrains to create a network of arts and science projects throughout the city. Barnett has written extensively on themes developed from his work in nonlinear design. His book Emergence in Landscape Architecture (Routledge) was published in 2013. After many years in professional practice leading to built work, Barnett now maintains an experimental practice culminating in competitions and exhibitions. Email: rodbarnett@wustl.edu