How might urban architecture — both exterior surfaces and interior cavities — provide habitable (or, at least, non-lethal) conditions for birds, bats, and other wildlife? This project aims to question our embattled notions of the word “pest” by bringing attention to city-dwelling species that interface with buildings — that is, animals that occupy the liminal spaces between inside and outside, “our” world and that of the “other.” This series of projects, installed at the Sullivan Galleries at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2015 as part of the exhibition “Outside Design,” interrogates the thickened space between inside and outside by addressing the notion of the building’s edge from the point of view of non-human, urban species.

A bird holds the cap of a plastic bottle in its beak. From security camera footage of the roof of the Columbus Building, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Courtesy Sullivan Galleries, SAIC

Screen capture from a Google Map of urban wildlife sitings on and around the campus of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Courtesy Sullivan Galleries, SAIC

Habitat Mapping at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago

Buildings are occupied not only by humans; other animal populations also thrive in them and are a significant part of the city’s ecosystem. This project explored how non-human species occupy buildings on the campus of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), focusing specifically on potentially inhabitable spaces such as building surfaces and cavities, spaces in-between buildings, and other peripheral, exterior areas.

To investigate the presence of urban wildlife on the SAIC campus, we initiated a documentation and mapping project. Combining independent field observations on animal sightings and potential “habitats” with advice from both biologists and SAIC’s office of Instructional Resources and Facilities Management, we identified points of interest around campus and documented them through various means. For example, we strategically implemented a series of “camera traps” — situations designed to capture wildlife in action and used often by both scientists and hunters — to closely monitor the presence of animal populations. We also scanned SAIC campus surveillance videos and culled footage showing animal appearances around building edges. Over the course of several months, we continuously documented those sites, as well as other zones along the SAIC campus boundary, using manual photography and videography in addition to the techniques mentioned. A combination of those means shaped a growing collection of footage exhibited at SAIC.

Another part of that documentation effort was a collaborative map launched initially to record animal sightings and to develop a means of commenting on the “habitability” of specific sites. Exhibition participants were invited to contribute observations to an evolving research document by “pinning” locations of their own animal sightings and posting evidence of urban wildlife on campus.

Façade, Art Institute of Chicago, July 15, 2015, 7:30am

Façade, Art Institute of Chicago, July 15, 2015, 3:30pm

Fire escape crows nest, Art Institute of Chicago, July 16, 2015, 3:20pm

Ants of the Prairie, No-Crash Zone, installation view, in "Outside Design," Sullivan Galleries, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2015. Courtesy Sullivan Galleries, SAIC. Photo: Tony Favarula

No-Crash Zone

The most significant cause of bird mortality in urban areas is collision with glass. Birds in flight are often unable to distinguish clear glass from open air, particularly if the glass is reflecting sky, trees, or other natural elements around a building. Currently, a growing number of organizations are beginning to address this underacknowledged killing spree. Bird advocacy groups such as the Audubon Society and the American Bird Conservancy are spearheading initiatives by working with researchers to develop bird-safe building guidelines for cities and are publishing reports to assist architects, developers, and building owners make more informed decisions about window design. Manufacturers are beginning to produce building materials and systems to prevent bird collisions, ranging from window decals — similar to those that we humans deploy to better “see” a glass sliding door — to patterned, fritted glass — intended to add visual interference to deter birds from what would be otherwise deadly flight paths. In the realm of sustainability assessment metrics for buildings — which has not typically focused on animal conservation — the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) has initiated a LEED Pilot Credit for testing “Bird Collision Deterrence.”

In this eco-urban dilemma, we see an emerging territory for exploration among these conflicts of interests. How, then, can we reconsider the glass window in a way that does not remove its function as an aperture for view and light? How can we design visual interference patterns into glass without undermining modernism’s dream of transparency? How can we consider the subjectivity of non-human species while still enabling and enhancing human desires, such as views from inside out?

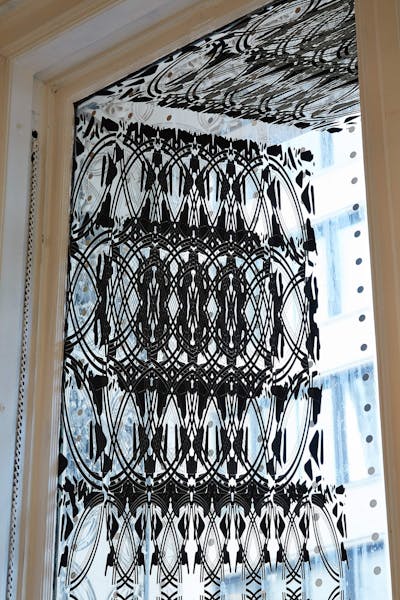

No-Crash Zone is a temporary renovation of a window in the Carson, Pirie, Scott Building in Chicago, Illinois, to make visible the logics of bird-strike prevention while still aspiring toward architecture’s preoccupations with the humanist subject.

With a nod to the tiling pattern framing the building’s windows, the project aims to create visual noise through the deployment of graphic ornament, reconsidering its role beyond agendas of aesthetic composition. The installation also taps into the fundamental construction of human vision by overtly referencing the one-point perspective developed during the Renaissance, as well as more contemporary optical tactics such as camouflage through pixilation.

Ants of the Prairie, No-Crash Zone, installation view, in "Outside Design," Sullivan Galleries, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2015. Courtesy Sullivan Galleries, SAIC. Photo: Tony Favarula

Ants of the Prairie, No-Crash Zone, installation view, in "Outside Design," Sullivan Galleries, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2015. Courtesy Sullivan Galleries, SAIC. Photo: Tony Favarula

Ants of the Prairie, Habitat Wall, installation view, in "Outside Design," Sullivan Galleries, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2015. Courtesy Sullivan Galleries, SAIC. Photo: Tony Favarula

Habitat Wall

Whether or not we like to admit it, many of our buildings already serve as habitat sites for urban animals. Bats frequently use attic spaces and warm cavities for roosting. Rats and raccoons occupy locations around dumpsters and loading docks. Birds are often seen on building cornices and nesting within exterior ornamentation.

In this project, we ask: If an exterior wall is already an inhabitable surface, how can those conditions be made visible and aesthetically intensified? How can a wall not only act as a façade but also be designed to perform as a living membrane? How can architecture raise awareness of typically “undesired” animals that are critical to our urban ecosystems? Can a new vision enable us to rethink the image and performance of the urban vernacular?

Responding to these imperatives, Habitat Wall is a prototype wall structure that incorporates conditions for bat and bird inhabitation into its design, aiming to give a spatial and tactile presence to species-specific considerations. Built from cedar, pine, and salvaged building materials, the prototype’s primary features include thin crevices of space, which allow for occupation by bats that typically might roost in attics, wall cavities, and other building features. Use of rough-cut wood and textured materials, such as recycled window shutters, enables bats to better land and climb into the cavities above. The mass and layering of the wood helps absorb heat during the day and provides better insulation and thermal consistency, which is important for bat dwellings. The prototype also includes bird nesting boxes and surfaces that are constructed for swallows and other cliff-dwelling birds.

Ants of the Prairie, Habitat Wall, installation view, in "Outside Design," Sullivan Galleries, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2015. Courtesy Sullivan Galleries, SAIC. Photo: Tony Favarula

Ants of the Prairie, Habitat Wall, installation view, in "Outside Design," Sullivan Galleries, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2015. Courtesy Sullivan Galleries, SAIC. Photo: Tony Favarula

Ants of the Prairie, Habitat Wall, installation view, in "Outside Design," Sullivan Galleries, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2015. Courtesy Sullivan Galleries, SAIC. Photo: Tony Favarula

Review

By Stuart McLean

Urban wildlife — birds, bats, rats, raccoons… The list could go on — there are so many of them. Yet, the term “urban wildlife” itself continues to carry connotations of the odd, the anomalous, of other-than-human bodies that have strayed disconcertingly into settings designed and built by and for humans. That this should be the case testifies surely to the tenacity of received distinctions between “natural” and “social” environments, despite the best efforts of much recent scholarship to displace or eliminate such distinctions. The various species of non-human animals who populate contemporary cities do not issue, however, from a realm of “nature” distinct from and external to a contrastively defined “human” world. They are rather the denizens of liminal, in-between spaces — spaces between buildings, rooftops, attics, loading docks, dumpsters, abandoned lots. The enduring human tendency to label such creatures as “pests” intruding into spaces where they do not belong is perhaps a product of the uncertainty that the anthropologist Mary Douglas associated with zones of ambiguity and classificatory uncertainty. In Douglas’s terms, such urban animals are, from a human perspective, examples of “matter out of place.”1 Yet, as another anthropologist, Victor Turner, pointed out, in-between spaces of this kind are not only ambiguous but also generative and transformative, the ‘liminal’ phase of initiation rites, for example, marking important transitions in a neophyte’s’s life-course and social status, such as the passage from youth to adulthood.2 The liminal zones of contemporary cityscapes, in which various species of urban wildlife make their homes, are similarly zones of transition, where insides merge into outsides, “domestic” spaces into “wild” ones, and where humanly constructed edifices are reappropriated for other-than-human purposes. The appearance in “our” midst of birds, bats, racoons and other non-human animals disrupts the familiarity and self-sameness of what we proprietorially think of as the human world, rendering our familiar spaces of habitation strange to thremselves, calling attention to other-than-human becomings that are close at hand rather than far away.

Nonetheless, our anthropocentric assumptions of uniqueness and privilege tend still to render us oblivious to this multifarious life that flourishes in our midst and in the midst of the worlds that we claim credit for having constructed. What would it take to unlearn such privilege and begin to see for the first time, or to see anew, what has always been there? Could the already established arts of human world making be redirected to such an end? Might architecture be able to help? After all, while buildings are often designed with human occupants in mind, humans are not, in fact, their only inabitants or users. Ants of the Prairie’s architectural projects rise to the challenge of accommodating human desires in ways that acknowledge and respect the co-presence of non-human animals: using decals and ornamentation as visual noise to prevent the bird fatalities arising from collisions with clear glass; designing an exterior wall as a “living membrane” deliberately incorporating crevices and boxes that bats and birds might use. In addressing itself to a community of users that can no longer be assumed to consist exclusively of humans, architecture itself becomes other. To adapt Heidegger’s terms, building is obliged to take account of other-than-human forms of dwelling.3 Rather than directing itself toward the clear delineation of insides and outsides, such architecture is concerned with openings, apertures, and interstitial spaces where humans and non-humans might encounter one another as fellow residents of the urban landscape. Who knows — might these one day be the settings for strange and unforeseeable trans-specific metamorphoses and becomings, where seemingly intractable divisions between culture and nature, human and animal, finally dissolve, and apartment dwellers launch themselves into feathered, avian flight? If Ants of the Prairie’s designs simultaneously address the concerns of the present and evoke a range of possible futures, they also cause us to view the past in a different light. As Lyotard wrote of the “postmodern condition,” the term “posthuman” does not necessarily designate the far side of an epochal break, that which follows chronologically “after” the human.4 Instead, it prompts us to question whether humans have ever been able to claim exclusive, proprietory rights to any time or space. Ants of the Prairie’s architecture does the same. Designed to accomodate the needs of contemporary, other-than-human urban populations, it reminds us, too, that the cities we, as humans, pride ourselves on building have never belonged only to us.

Notes

Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (London, UK: Routledge Classics, 2002 [1966]).

Victor Turner, The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1970).

Martin Heidegger, “Building Dwelling Thinking,” in Basic Writings, ed. D. F. Krell (New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1977 [1951]).

Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1984 [1979]).

Biographies

Joyce Hwang, AIA, NCARB, is the Director of Ants of the Prairie, an office of architectural practice and research that focuses on confronting contemporary ecological conditions through creative means. In that capacity, she is currently developing a series of projects that incorporate wildlife habitats into constructed environments, including Bat Tower (2010), Bat Cloud (2012), and Habitat Wall (2011; 2015). Hwang is a recipient of the Architectural League of New York’s Emerging Voices Award (2014), a New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) Fellowship (2013), two New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) Independent Project Grants (2008, 2013), and two MacDowell Colony Fellowships (2011, 2016). Her work has been exhibited at the Venice Architecture Biennale and the International Architecture Biennale, Rotterdam, among other venues. Hwang’s projects and writing have been featured in international online and print publications, such as Good, Curbed, Praxis, Architect Magazine, Green Building and Design, AV Proyectos, Bracket, MONU, and Next Nature. She is a co-organizer of the Hive City Habitat Design Competition and a co-editor of Beyond Patronage: Reconsidering Models of Practice (Actar, 2015). Hwang is a registered architect in New York State. She has practiced professionally with offices in New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Barcelona and collaborated with the office of Carlos Ferrater in the invited competition for the new international terminal at the Barcelona Airport. Hwang received a post-professional Master of Architecture degree from Princeton University and a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Cornell University, where she received the Charles Goodwin Sands Memorial Bronze Medal. Email: jh96@buffalo.edu

Stuart McLean is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Minnesota. His work theorizes the intersection between the material world and the human elaboration of cultural meaning by considering the variety of ways in which human beings have understood and articulated the relationship between their own acts of imagination, remembrance, and self-identification and the material processes giving form to their bodies, their material environments, and their world. McLean’s publications include a series of important essays about memory and imagination, with special emphasis on the culture of Ireland, as well as the book The Event and Its Terrors: Ireland, Famine, Modernity (Stanford University Press, 2004). He received a a BA in English Literature from the University of Oxford and a Ph.D. in Sociocultural Anthropology from Columbia University. Email: mclea070@umn.edu