Listening at a distance of 100 feet

Of course and every year I go out far abroad on the intent that our age will announce civility and create a dispensation to all omens of evil. Now all are in rage at the cry of our war, dusting away all vanity to bring on a meeting dedicated to our ardor. We meet at a great battle of horror. We defer from more, to come bring a new decision. We advise this place and what we see here who gave their lives that an angel at night leads. It is altogether fitting to our old sense.

And of our sick we cannot dedicate, we cannot consider all on the ground. The remaining living and dead who held dear lad above the proud that struggled in fear. I would never know nor long remember misery, but I can never forget the debt here. But just for us the living rather to divide here who have vanished words, which they ought to have were it that nobody had death. But with the refuge to be dedicated to the great path, I mean for us to believe our dead. We take a piece devoted to the costs, which great as the ocean, that we here rightly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain. These names are called and shall have a new earth that even in the interminable abysmal odes of my people are ever part of the earth.

Listening at a distance of 80 feet

I’ve sworn that every year I’ll know how far I brought on discontent, a new age in uncivility and educated to the proper disposition that a meaning is greater than evil. Now all are enraged in the grind of our war, testing the way all vanity here can bring on such meaning dedicated to long endure it. We are met on a great battle wielded for more. We have come to bring a new decision. Be advised of this place of what we see here, who gave their lives at an age one might live. It is all together fitting to prepare our old and new dues.

But, for our sake, we can not dedicate, we can not consider it, we cannot crawl on this ground. The remaining living and dead, who we held dear created a love above our proud dead who struggled here. Ah world, you’ll never know, nor long remember the misery here, but it can never forget the dead here. It has forced the living, rather, to bide care here, to a vanished work which they ought to have or that for nobody had asked. It is a refuge to be dedicated to a great task, a meaning for us, that for these, our dead, we take a piece devoted to that cost for which a grave is a posthumous notion. That we here rightly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — as his name is our God — shall have a new earth of Eden and the atonement of a vigil, by a people, forth ever now parched under earth.

Listening at a distance of 40 feet

Forsworn in seven years I know how far they brought for our discontent: A new nation, can it see liberty? And dedicated to the proper decision that all men are great and equal. Now we are engaged in the Greys at a still war, testing the way our damnation, or any one so can’t see and so dedicated, can long endure it. We are met on a great battlefield yielded for war. We have come to dedicate a portion of it. Feel the vile resting place of what we see here — who gave their lives and opposition. It is all together fitting and proper that we do this.

But, for our sake, we can not dedicate, we can not consider it, we can not halt our ground. The bereavement, living and dead, sheltered in this part of it. Ah world, Ah world, to have to, for what will, nor long remember what is we may ‘err, but it can never forget what they did here. It has forced the living, rather, to head and laid here to vanished work which they entrusted us in order to save the nation. It is rather fierce to bare, dedicated to a great task remaining for us that for these our dead we take a priest devoted to that cost for which a grave is a blasphemous devotion. That we here leave resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — as his name is our God shall have a new birth under heaven — and that covered over the people, the people, a people, all now perished under the earth.

The above “environmental translations” of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address bring the speech into the context within which it was originally read. They enable us to consider writing as a spatially representative, phonographic form. It returns this monument of American English to the time and space within which it appeared and opens this work to the possible experiences of the audience who first heard and misheard it.

There are over six printed versions of what people think they heard Lincoln say on November 19, 1863. Most are similar, but at least one surviving transcription of the speech — completed by a journalist from the Illinois newspaper, the Centralia Sentinel—was transcribed into far less poetic prose than the original. Of those close to the official version, all have various differences in emphasis. Most listeners who were not reporting on the speech could not recall with accuracy what they heard but appreciated Lincoln’s dedication of the first national military cemetery at Gettysburg and his mournful reflections on death and the Union’s future commitment to the war.

In the weeks following his delivery of this speech, Lincoln reviewed various transcriptions and decided which of the transcribed versions of the dedication would be the official Gettysburg Address that we know today. However, as a read and unrecorded speech, originally listened to by an audience of thousands, the address was and is not the stable document that we monumentalize today. “Listening to a speech” emphasizes the address as a fluctuating document read in a large landscape to thousands of people and that reflected on themes of death, sacrifice and war. With its similarities and differences to what we understand of the original, the environmental translations shown above also emphasize language as something that can record a representation of sound and space, much like a phonographic recording. It is a representation of the struggle to listen among crowds and at a distance and the fragile, unpredictable aspects of listening and apprehending any spoken language.

I chose to create a phonographic, spatial representation of the Gettysburg Address due to most Americans familiarity with the document, the evocative context within which it was first delivered, and because of its historical variability due to the fact that so many people heard it slightly differently. But the original material was manipulated with techniques that could be applied to other documents.

I created “Listening to a Speech” with several simulation and transcription tools that can be applied to other spoken documents and that can create complex representations of language, comprehension and miscomprehension and notions of space and distance.

The creation of “Listening to a speech” begins with a recording of a contemporary reading of the “official” Gettysburg Address. This audio file was fed into a digital audio workstation (DAW) with a convolution reverb processor, utilizing an impulse response file that simulates a large, open landscape.

When fed through the DAW’s processors, the Gettysburg track sounded as if it were being read in a large open space in the distance. Two additional audio tracks were also fed through the DAW at the same time: one of randomized white-noise that simulates the signals of crowds and is used to test hearing aids and the other a similar track of white nature noise. Various distances were simulated with the convolution reverb and volume settings. The resulting, slightly reverberative, cacophonic audio of the address was directly fed into a digital speech-to-text processor that transformed the audio of spoken language into writing.

When listened to at a distance and with (or without) the additional audio interference, higher-pitched spoken tones are more difficult to perceive. In some cases, such tones simply disappear. This includes the sounds “phh,” “sss,” “thh,” and “huh” that are common in words such as “father,” “seven,” “the,” and “here.” The remaining sound of the word will appear broken and sometimes will blend with sounds before or after. Additionally, both we and the speech-to-text processor mishear in rhyme. So, a word such as “heaven” might sound like “eleven” at a distance or “hear” might sound like “ear.”

The three versions of the speech presented are based on the results of the speech-to-text processing. In each version, the DAW’s settings were changed to represent a greater distance from Lincoln. The speech-to-text processor suggested the most likely version of what the audio is stating, but it also offers alternate word possibilities for correctly identifying the language of the recorded Gettysburg reading.

Rather than taking the suggested speech-to-text transcriptions as the final versions, I further studied the etymology of the speech-to-text processor’s word suggestions and their historical usage. I modified the digital transcription to represent language that would have been understood in the mid-19th-century United States and that would have addressed the subject of war, loss, and mourning. Thus, the final environmental translation of the original represents both aspects of location (distance, crowds, and nature) and aspects of time (historical uses of language).

DAW utilizing recorded speech, convolution, and interfering sounds

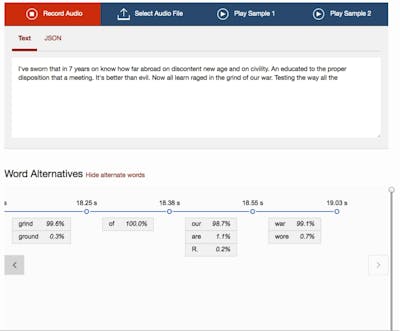

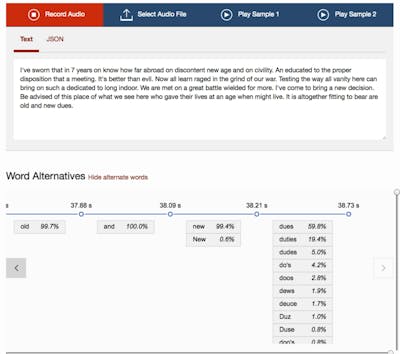

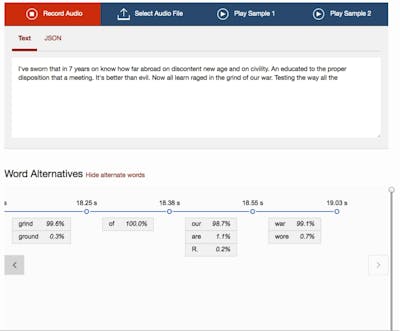

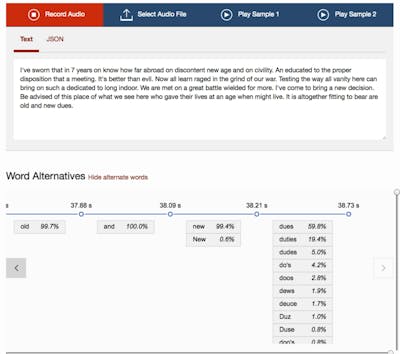

Speech to text processing from DAW

Speech to text processing from DAW

Review

By Charles E. Morris III

A strange yearning, historical ache: Walt Whitman, smitten though he was, never got close enough to hear Lincoln’s breathing.

As I complete this response to David Gissen, I am in the afterglow of hosting at Syracuse University the 15th Biennial Public Address Conference, a beloved symposium in the discipline of Rhetorical Studies featuring leading lights and rising stars delivering papers about speech that has mattered in U.S. history. Lincoln’s face, photographed from the solemn James Earle Fraser bronze replica on campus, constituted the program cover. That Lincoln should represent this venerable gathering is altogether fitting and proper. Lincoln’s discourse has been central to the field from its inception, and a lively 1987 panel on him in part inspired the conference founding. My own preoccupations as a queer historical critic and fifteen years’ puzzling over the vicissitudes of Lincoln (sexual) memory also influenced my choice of the conference theme: “The Conceit of Context.” The hope is to unsettle any excessive confidence in this key term’s taken-for-granted understanding, and to kindle reimagining and reconceiving of how we might “do” context.

With such motives in mind, David Gissen’s “environmental translation” of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address has captivated me. His creative simulation and transcription, “Listening to a Speech,” offers a provocative engagement with the relations among language, sound, and space — of proximities and bodies and meanings, of the contexts of hearing and mishearing. The difference that embodied distance makes, as Gissen’s experiment exhibits, tells us much about a “fluctuating document” even as familiar and canonical as Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, and the “fragile, unpredictable aspects of listening and apprehending any spoken language.” At a moment in the history of Rhetorical Studies when researchers are propelled by the turn to “field” but have yet to fully figure out how to productively apply the prospects of ethnography to rhetorical pasts, perhaps especially as we seek to strengthen our grasp of the sensorium of experiential and ephemeral history (however inevitably elusive it may be), Gissen’s soundings constitute an enticing clarion call. Across disciplinary lines we have much to share in conceptualizing historical reconstruction.1

Gissen’s auditory scene and its implications left me mulling two concepts I would like briefly to explore as potential contextual projects central to the life and afterlives of the Gettysburg Address. First, I am curious about acoustic shadow. All these years later, I’ve never forgotten this observation in Ken Burns’ series The Civil War: “More than once during the Civil War, newspapers reported a strange phenomenon. From only a few miles away, a battle sometimes made no sound, despite the flash and smoke of cannon and the fact that more-distant observers could hear it clearly. These eerie silences were called acoustic shadows.”2 Acoustic shadows evidently were influential in shaping the second day of battle at Gettysburg; confederate strategy, which hinged on the auditory cue of artillery fire, faltered because Ewell never heard the sound of Longstreet’s guns owing to refractions of terrain and weather.3 In imagining cognitive, affective, and political variations of acoustic shadows and spotlights, in imagining the copious meanings of proximity and distance (however many feet one might stand from the platform), we might consider the diverse array of contextual reasons that produced in the ears of audience members silence, static, melody, distortion or amplification and thus shaped (mis)apprehension. Gabor Boritt’s The Gettysburg Gospel, for example, noted the panoply of translations in accounting for diverse “echoes” of the Gettysburg Address in press coverage. Familiar is the most obvious case of ideological terrain and temperature that produced seething and singing interpretations of “All men are created equal.” Many in the press seemed not to hear Lincoln say anything at all, even as folks cheered and “a captain with an empty sleeve buried his face in his good arm, shaking and sobbing aloud,” as Lincoln’s memory politics — “The world will little note nor long remember” — resounded.4

The other concept on my mind is reverberation. Gissen’s listening moves toward Lincoln, and I have long been interested in the performative recitation of the Gettysburg Address in increasing distance across space and time, efforts that seek proximity to Lincoln’s voice and vision even as context changes, sometimes radically, how Lincoln’s understanding is uttered and embodied. Sociologist Barry Schwartz has done much in teaching us how generation and national circumstance change the meanings of the speech,5 but what of those contexts in relation to the other non-linguistic dimensions of saying and sounding that affect translation, interpretation, circulation? People at the time, across the expanse of the country, read swatches of the text aloud. At the 1913 and 1938 reunions, laureled veterans of the epic battle (many depicted in archival footage with ears cupped, straining to hear) listened again to Lincoln’s words, sitting among a throng not yet born in November 1863. Multitudes of Americans for more than a century have spoken Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, especially in the nation’s classrooms, but also on diverse epideictic occasions calling for words of consolation and rededication, such as on the first anniversary of 9⁄11. Translations are inventional and receptional, and performative inflections reflect and refract, shaping echoes of Lincoln and how they might be heard.

Especially as I think about those boys with language-based learning disabilities at the Greenwood School in Vermont, memorizing and movingly reciting “The Address,” and as I imagine how queer kids and their teachers might benefit from a queer Lincoln rhetorical pedagogy,6 I hope that we might all find meaningful inspiration, vexation, and mobilization in David Gissen’s attunement to listening at distances.

Notes

1

See, for example, “History’s Apparatus: An Interview with David Gissen,” Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices, and Architectural Inventions, ed. Geoff Manaugh (Reno, NV: Nevada Museum of Art; Barcelona, Spain: Actar, 2013), 49 – 72.

2

Ken Burns, “The Universe of Battle,” The Civil War (PBS, 1990).

3

Charles D. Ross, Civil War Acoustic Shadows (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing, 2001).

4

Gabor Boritt, The Gettysburg Gospel: The Lincoln Speech that Nobody Knows (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006), chapters 5 and 6, and p. 118.

5

Barry Schwartz, “Rereading the Gettysburg Address: Social Change and Collective Memory,” Qualitative Sociology 19 (1996): 395 – 422.

6

Ken Burns, The Address (PBS, 2014); Charles E. Morris III, “Sunder the Children: Abraham Lincoln’s Queer Rhetorical Pedagogy,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 98 (November 2013): 395 – 422.

- Tags

- landscapepoliticshistoryrhetoriclincolnacousticsenvironmental translation

Biographies

David Gissen is a historian, theorist, curator, and critic whose work examines histories and theories of architecture, landscapes, environments, and cities. His recent work focuses on developing a novel concept of nature in architectural thought and experimental forms of architectural historical practice. Gissen is the author of Manhattan Atmospheres: Architecture, the Interior Environment, and Urban Crisis (University of Minnesota Press, 2014) and Subnature: Architecture’s Other Environments (Princeton Architectural Press, 2009), and he edited of the “Territory” issue of AD Journal (2010) and Big and Green (Princeton Architectural Press, 2003). His essays have been published in journals such as AA Files, Cabinet, Grey Room, Log, Quaderns, and Thresholds, as well as a wide range of magazines, newspapers, blogs, and books. His curatorial and experimental historical work has been staged at the Museum of the City of New York, the National Building Museum, the Yale University Architecture Gallery, the Toronto Free Gallery, and the Canadian Centre for Architecture, among other venues. Gissen is currently an associate professor at the California College of the Arts. Email: dgissen@cca.edu

Charles E. Morris III is Professor and Chairperson in the Department of Communication & Rhetorical Studies, College of Visual and Performing Arts, at Syracuse University. He is co-editor, with Thomas K. Nakayama, of QED: A Journal of GLBTQ Worldmaking, published by Michigan State University Press. Morris is the author of Queering Public Address: Sexualities in American Historical Discourse (University of South Carolina Press, 2007). Selected recent essays include “Context’s Critic, Invisible Traditions, and Queering Rhetorical History,” Quarterly Journal of Speech (2015); “Lincoln’s Queer Hands,” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 18 (Spring 2015); and “Sunder the Children: Abraham Lincoln’s Queer Rhetorical Pedagogy,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 99 (November 2013). For his work on LGBTQ memory and history, Morris has twice received the Golden Monograph Award for article of the year (2003, 2010) from the National Communication Association (NCA), as well as the NCA’s Karl Wallace Memorial Award (2001) for early career achievement and its Randy Majors Award for Distinguished Scholarship in LGBTQ Studies (2008). In 2016. Morris was named a Distinguished Scholar by the Rhetorical and Communication Theory Division of the NCA. Email: cemorris@syr.edu