Sierpc, Poland: a world of graves for my parents. A mythic world for me.

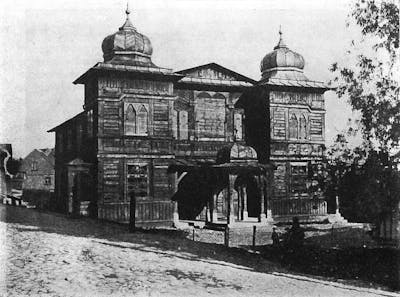

There my paternal grandfather, the shoichet, smooths his slaughtering knives on silk socks and my maternal grandmother sews men’s underwear. Mama and her sisters sweep the floors with sand and sleep head to toe like sardines in one bed. The streets are muddy. The wooden synagogue has Byzantine domes. People go hungry except Friday nights and holidays. My father passes meat to his sisters under the table in exchange for bones. Dogs chase him on his way to cheder.

Those who left never went back.

Daddy died. Mama married Leon, a widower from Sierpc. He died. Mama died.

It’s pronounced Sherptz, but my family called it Sheps.

§

A mover sets Mama’s captain’s chair on the sidewalk, neatly wrapped in blue quilted padding. It stands under a pin oak, muffled and serene, on our street of Victorian houses. Seven cartons join the chair, containing music scores, photos, Stangl dishes, my father’s writings.

Things used. Things loved. A chair that is more than a chair.

The furniture lines up in surreal dignity. A swaddled lamp. A brown-padded sideboard. A lumpy tower — the kitchen step-stool chair.

Movers carry the sideboard to the porch. I prop open the storm door.

The house phone rings. I hear Herbert say, “She’s outside, hold on.” He hands me the phone. “It’s Michael.”

“Hi, Mom,” Michael says, “what would you like from Sierpc?”

“Sierpc? Why are you …”

“Elpida had an archeology conference in Torun.”

“Oh my god! Grandma’s furniture is coming in the front door! The movers are bringing in Grandma’s furniture as we speak!”

Michael laughs, a deep, satisfied laugh.

The connection crackles. He’s in the Jewish quarter. The synagogue is gone. Jewish houses gone. Except for the city square and government buildings, most of Sierpc is postwar construction.

“They lived on Jewish Street,” I say.

“That’s where we are. The translator says it’s Baker Street now.”

(Children walk to and from the bakery in pairs, carrying two-handled pots of Sabbath stew.)

“No point going to the cemetery,” I say, “you wouldn’t be able to read anything, anyway.”

“Tell him bring stuff for tourists,” Herbert shouts.

“They make beer,” Michael says, “Sierpc beer. Gotta go.”

“Pictures,” I cry, “I want pictures!”

I clutch the silent phone, the moment holding its cache of time like a seine net drawn tight over its weight of fish. I draw in Herbert, draw in the movers, feeling the moment ripple outward and circulate back. I phone our son Yuri and my aunt Dinah; they’re not home. I call a close friend. She says the story is powerful and wonderful because it demonstrates orderly design in the universe.

§

The first time I use one of Mama’s kitchen things my hands become her hands, those puffy hands softened with lemon juice. If I were religious I would say it’s a sacred moment when I first scramble eggs in her green glass bowl, dice an onion with her paring knife. These things are Mama, are a way she used her hands — she is the object and the task and, for awhile, in part, I become her in the doing.

I scrub two potatoes, puncture them, and put them in her stove-top potato baker. Mama used it to save money on gas. It has a perforated steel plate with an arched handle, a small footed plate for the potatoes, and a stain-speckled, domed aluminum lid. She stored it in the oven. When the oven was in use, she put it on the step-stool chair.

I set the baker on a burner and adjust the vent. The lid resembles a Byzantine dome on the Sierpc synagogue.

A familiar smell wafts into the kitchen. Roast chicken? Chicken with onions and carrots? Kasha varnishkes? No matter what Mama cooked, it smelled like this. It’s the smell of my childhood. It’s the smell of our visits, Mama opening the door, clapping her hands to her cheeks, crying.

I see her move about her tiny kitchen, a housecoat over her clothes. She washes a chicken, pats it dry with a paper towel, and puts it in the roasting pan. Rubs salt on it. Cuts onions, carrots, and potatoes in chunks right over the pan. Before lighting the oven she sets the potato baker on the step-stool chair. She roasts the chicken covered for an hour, basting occasionally, then uncovered half an hour until it browns. As soon as she takes it out she puts the baker back in the oven to make space on the chair.

Miraculous object, lying dormant for six years, preserving this ghostly essence. Perhaps particles lingered in the sealed air, adhering to steel and aluminum. Particles, molecules, swirling, falling — whatever the physics of it, here is Mama’s potato baker on my stove, exhaling a lifetime of her cooking, perfume of roast chicken.

I lean against the counter. The smell gradually dissipates.

Herbert walks in. A trace lingers.

We marvel together, and then it’s gone.

§

Michael sends two empty Sierpc beer cans, a Sierpc beer glass, and a photo of the grassy lot where the synagogue stood. Filled with pebbles, the cans and the glass serve as bookends in my study.

§

Mama’s Yiddish books went to the Yiddish Book Center, except for The Community of Sierpc, Memorial Book. Six hundred pages of Hebrew script, impenetrable as the stone wall of amnesia. On the cover, beside a drawing of the synagogue, teardrops from the Yiddish title’s last letter fall into an overflowing goblet; an eternal light on the spine. I leaf through photos of solemn schoolgirls in white collars and long skirts. Young men in high skull caps. Bearded old men. Youth groups in uniforms. Some public places identified in English — the synagogue, the prayer house, the Old Market, the Town Hall.

My stepfather used to say the book was written for future generations.

But we can’t read it, I said.

§

They weren’t storytellers. My parents and aunts grudgingly told a few. My Bube, born in Sierpc, said nothing. Their reticence leaked shame; I recoiled from Yiddish culture. Their past was a fiction, a tiny landscape sealed in glass.

Secretly, though, Daddy was writing. For thirty years he managed a small silk mill in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and wrote in his office. When the mill closed he hid his writings in a blue zippered hatbox. Mama discovered them after he died. She translated three memoirs for me and stored the case in her basement.

After she died, I touched his papers, his handwriting. Poems and political plays in English. Memoirs in Yiddish, collages of the Old World and the New. He wrote his father’s virtues on the backs of price lists for used machine parts. His mother’s latkes on the backs of ads for looms. Chanukah memories on invoices from Gates Rubber Co. and Eagle Beef Cloth Co.

A friend translated the remaining memoirs.

From ages six to nine, he writes, he went to a little cheder in the house of Reb Yosef, a fanatical rabbi who whipped the boys if they laughed or asked questions. A kinder spirit reigned at home. His father lovingly taught the children prayers and songs. His mother ran the large household with little money. The toes of his shoes opened like alligators’ mouths and swallowed mud. When the buttons on his good jacket popped his mother sewed him into it.

The rhythm of life was set by prayers. Every action began with a prayer — eating, washing hands, stepping from room to room.

He learned prayers and sacred songs from his father. He memorized the Torah, studied violin and mandolin. Had a beautiful voice. Learning, learning — he loved to learn. He eavesdropped on his sisters’ lessons, hungry for secular history. His mother allowed it briefly, then, alarmed by his passion, told his father it distracted him from the Torah. “The next day … I had to stay in a different room and felt like one starving who sees and smells food and can’t reach it.” Hunger, hunger. Empty belly and yearning mind. Happiness was the Sabbath and holidays, family rituals graced by food. “My Grandmother’s Shevuoth Blintzes.” “To the Feast of Purim.”

An idealized memoir, “My Father,” is dedicated to his mother, brother, and sisters and their families “who perished in the Warsaw ghetto.”

“Who didn’t know or at least hear of Yankl Shoichet?” he writes. “Not only as the expert shoichet but as a person who was always ready to offer advice or a favor to whoever needed it. … My father sang all the time regardless how he felt inside of him with trouble of making a living or sickness or children. He always sang and with a smile helped wherever help was needed.”

His sisters, mentioned occasionally, are rarely named. His brother is absent. “After we were done with our Sabbath meal my father ordered all the children to take a nap. We lay down and kept silence until my father and mother were asleep, then we either read some books that were prohibited to read on the Sabbath or we made our way out into the street through the window.”

§

I google Sierpc occasionally, a hopeful ritual ending at maps and tourist sites. Today a startling new link heads the list. JewishGen. The Community of Sierpc: Memorial Book. Translation of Kehilat Sierpc; Sefer Zikaron.

Heart pounding, I enter. Parties and Institutions. Once Upon a Time. “The Great Flood of Sierpc.” “Street Names in Sierpc.” “Chanukah Memories from my Town of Sierpc,” by Motl Rajczyk.

My father.

“We had to make a book out of ashes,” the editors write, “… but thanks to the stubbornness of a few … our remembrance has reached its climax after six years. Important material had to be collected bit by bit … with great respect for all our loved ones who were there and are no longer. We, the remaining townspeople of Sierpc … felt that we have to fulfill a sacred obligation, to leave a testament to our community. We could not rest or stop until we finished our labors, this holy work of sorrow and pain.”

§

After WWII, memorial committees asked former residents of wrecked communities to write memories and histories of their home towns. The writings became books, some in Yiddish, some in Hebrew. In the 1950s and 1960s over two thousand were published. I recognize two names on the American book committee: my parents’ friend Golda, who may have solicited Daddy’s memoir, and Leon, who became my stepfather. JewishGen, in its Yizkor (Memorial) Books project, has had about one hundred books translated into English and put online.

Deeply grateful, I order a hard copy.

I start with The Holocaust.

Nazis entered Sierpc in September 1939. On September 28 they burned the synagogue and shot a teenage boy, blaming Jews for the fire and demanding a “contribution” for repairs. Humiliations escalated. Jews forbidden to use electricity, walk on sidewalks, be outdoors after four p.m. Devout men beaten, their beards hacked off, carrying rocks back and forth for hours, digging useless holes. Girls forced to wash toilets in the jail with their bare hands.

The ragged shadows are Daddy’s mother, sisters, and brother. Mama’s aunt, grandparents, and cousins.

(I’m six. Daddy lies across the bed, crying, face down. “My mother is killed in Warsaw,” he sobs. How did she get to Warsaw, I wonder.)

On November 8 Nazis lined up three thousand Jews, six to a row, in the market square. The Fireman’s Orchestra, playing lively marches on pipes and drums, led the mass expulsion. Old, sick; toddling, pregnant — the SS forced everyone to run, whipping them into speed, shooting stragglers. At the railway station soldiers shoved them into airless cattle cars without food or water. For days, by train and on foot, they were starved, beaten, shot, drowned, and finally dumped on the outskirts of Warsaw.

The grotesque music plays. Bube Manye struggles to keep up. Her daughters struggle to shield her. We were in Dante’s Inferno, the writer says.

The writer, Golda Goldman, was like a cousin to my father. Having traveled through hell with his mother and sisters, she knew the secrets that poisoned him.

I hear him singing kadish, tormented by guilt, a fire that consumes but is never exhausted.

His memoirs stop at 1923, the year he left Sierpc. Safe in America, he inhaled airmail letters from home, their melodies, their darkening harmonies. His heart locked his tongue and his pen. They ate latkes in Sierpc, he wrote; they perished in the Warsaw ghetto. In the gap between latkes and perished he hid twenty years, drawing his cape of shadows around my questions.

As for Mama, she was so ashamed of her past, she let the holes in her earlobes close up. “Primitive women, they have holes in their ears,” she said, and wore clip earrings until pierced ears became fashionable in America.

§

For relief, I turn to “The Holders of Religious Posts in Sierpc,” skimming the chapters on rabbis and cantors, reading the chapter on shoichets. The historian, a rabbi, remembers fierce disputes over hiring a new shoichet. The Hasidic sects squabbled for many months, he writes, and candidates came and went. One day a ritual slaughterer from Sochocin applied for the position. “He was a young man … tall, head and shoulders taller than everyone, with a face as handsome as an angel, with a black beard and two black, fiery, hypnotic eyes. He always had a smile on his lips, and his joy and friendship were infectious.… The women simply fell in love with him and wanted Reb Yankel Reitczyk to be the shoichet of the Sierpc community.”

Yankel Reitczyk. My grandfather. He rises from the historian’s memory like a genie from a rusty lamp.

“The shoichet was loved greatly in the Sierpc community. [He was] a fine prayer leader, an expert shoichet and mohel, with a splendid appearance, wise and intelligent, getting along well with people, a good soul with a heart of gold, G‑d fearing but not fanatic. He was a modern Orthodox Jew, who was loved by all classes of people.”

I read the passage and cry, read my grandfather’s name and cry. I tell the story to Herbert, to our sons, to our granddaughter, to close friends. When I say, “I found my grandfather” or “Reb Yankel Reitczyk, my grandfather,” something old and deep wells up, love or sorrow or guilt, something suppressed or cherished, released from captivity.

“If anybody had a … dispute,” Daddy writes, “they didn’t turn to the rabbi or judge, but came to my father.… When a cow was about to die during the night the butcher would knock on my father’s window and he would … slaughter the cow to save the butcher’s hard-earned property.… Everyone loved him, the entire congregation, and he loved them, rich or poor, all walks of life.”

Cracking like river ice, I flow into a world with real dimensions.

“I found my grandfather,” I say, touching the heart that passed to my father and beats in me, in our sons, in our grandchildren.

Visiting sick people is one of the virtues, he preached, and he kept on visiting during the 1917 typhus epidemic, ignoring the “contagious” notices. When he caught typhus he refused a hospital bed until it was too late.

Daddy was almost thirteen, preparing for his Bar Mitzvah.

“The life of this thirty-eight-year-old tree was cut forever,” he writes.

The historian says it was a tragedy for Reb Yankel’s family, losing him after losing Esther. I stop. Daddy’s sisters were Malkah, Necha, and Breine. I never heard of Esther till she flitted through a passage about his father. “When my oldest sister Esther died during WWI, my father did not sing for the longest time, as it had been his habit, going to and from the prayer house.”

Daddy was the oldest child; I assumed “oldest sister,” was a mistake in translation or transcription and imagined a sickly toddler he barely knew.

The historian says, “Esther died of typhus at the age of fifteen. She was the spitting image of her father … tall, well-grown … with eyes like … sapphires and hair that covered her head like a crown.”

Fifteen! I scour Daddy’s memoirs. Purim preparations. “My sisters buy fresh kerosene to wash their hair, also new combs and ribbons. … My older sister’s boyfriend walks in. He just came from the barber shop and he smells like a hospital.”

His beloved older sister, cherished in silence.

He had his Bar Mitzvah a month after his father died, becoming a man while the earth shook. His destiny tasted sour. He told his mother he would not study to be a shoichet. He joined a youth group, sang in a chorus. At sixteen he’s a haunted-looking boy with big eyes and short hair. No forelocks, no high skull cap. Cousins in New York offered him a job. He left Sierpc at nineteen and settled in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, managing their little textile factory. “I am the only one in our family,” he writes in English, “who knows how it feels to be on his own.”

Before he could earn enough to bring anyone over, his mother was killed by a bomb dropped on a Warsaw ghetto hospital, his sisters died, and his brother Schloime vanished. Years after the war ended an airmail letter arrived from Necha, in Tel Aviv, a blip of joy in a settled grief.

Did Schloime escape, too? The family album shows a modern, confident young man in 1934, striding down a city street, wearing an army greatcoat, cap, and boots. Absence creates belief: he got to Canada and didn’t know how to find us. I imagine a family, children — at least one girl cousin. I sense Schloime alive somewhere. Whenever I see the name Reichek in print I vow to find out if we’re related.

§

Like an archeologist excavating a site, I dig through the book, unearthing details that match and extend my parents’ stories, satisfying a hunger to see beyond crumbling tombstones. Photos of Schloime in a play and my aunt Breine in a youth group. My father, a “young lad,” studying in the old Beis Midrash. The fanatical teacher, Reb Yosef, pushed into the river by an enraged student. The bakery on Jewish Street where children carried the heavy pots of Sabbath stew — two bakeries, actually, run by hard-working women, their ovens in basements reached by rotting wooden steps.

I devour streets, houses, shops, people, and customs, knowing memories are part fiction — mine layered on my father’s and on those of the memorial book’s writers. Daddy’s past mutates. He wrote about Sierpc as if he were born there, but he was eight when he arrived from the village of Sochocin. Did he conflate the two stetls or did I misinterpret something? I notice the sadness in his memoirs, his longing for the rituals of life, the prayers and blessings, the holiday meals.

History records the selective memory of selective witnesses. My parents grew up in the same three-family house; Daddy’s family on the first floor, Mama’s on the third. But my maternal family left no impression. No witness remembers my grandmother Idyla, her four daughters, her parents and sister, and her vagabond husband. The only trace I’ve found is Mama’s youngest sister in a school photo. From the caption I learn their surname, Oppenheim, was originally Openchaim. Where’s my great-aunt, the wigmaker? Where’s my great-grandfather, the Torah proofreader, so devout he wouldn’t eat fish on the Sabbath for fear of breaking a bone?

Sierpc, itself, that muddy village, mutates into a lovely old city crossed by three rivers and surrounded by farms, orchards, and mountains. In 1938 the population was ten thousand with a long-established Jewish population of four thousand. Jews were tailors and shoemakers, glassmakers and clockmakers, fishermen and butchers, fruit and vegetable dealers.

Poles called it Sherptz; Jews called it Sheps.

Leafing through the book’s appendix one night, I stumble on fragments of anguished letters to Yiddish-American newspapers as early as 1939, reporting forced labor and humiliation, one from Mama’s cousin Beryl. Newspaper clippings about the synagogue burning, the expulsion. Thirty-three Sierpc men write to The Forward from Vilnius (Vilna) — they’re barefoot, sleeping on the floor of one room, eating one meal a day. On December 26, 1939, they appeal to the Sierpc Relief Committee in New York for money and visas. Their thank-you letter for 300 Litas, dated January 28, 1940, includes a receipt signed by each man in the group. Number 4 is Schlomo Reitczyk. Schloime. There’s even a photocopy of the original receipt, with his signature.

His writing is delicate and cramped. I trace the curves.

Did he get a visa? Was the New York Sierpc Relief Committee in touch with our family? Did anyone notify Daddy his brother was alive, needing help? Alas, my parents discussed serious matters in Yiddish; I constructed narratives from scraps. I still do. I imagine us in Brooklyn for an emotional reunion with Golda. I imagine ten anxious adults in my grandparents’ living room, having sent me and my cousin next door. I imagine Zeyde in his stuffed chair, arms crossed and eyes blazing, Bube serving tea and cookies, Golda on the lumpy couch, telling horror stories about their friends and neighbors. About Daddy’s mother and sisters. About herself. Zeyde ranting in rage; everyone else crying.

Mama’s guilt erupted late in life. After the war, she said, Daddy wanted to pay a head-hunter $100 to look for Schloime, but Zeyde said they’re all thieves, don’t waste your hard-earned money.

The book ends with a necrology. Surnames and maiden names; ages at time of death. Six entries for Reitczyk. I read slowly. My grandmother, Bube Manye. My aunt Malkah, her husband, and three sons. My aunt Breine. But who is Chana Reitczyk? Is there another family with the same name? A different Schlomo Reitczyk? My brain refuses to process what my eye sees. Schloime had a wife, Chana, and they had a daughter. Schloime and Chana died at thirty; their daughter, not named, was two.

Imagined, but not imaginary.

Breine, Daddy’s youngest sister, died at twenty-seven, probably in 1941, with Bube Manye. I linger at the numbers, watching them toss and swirl like dry leaves in a wind. Out of the shadows my grandmother emerges into her untold story, a gaunt, pregnant woman in a long baggy dress. It’s 1914. She gives birth to Breine while German and Russian patrols run through the streets and bombs fall. Three years later, when typhus rages in the house, she nurses Esther, nurses Reb Yankel. Who helps her? Who goes to market, cooks, tends the younger children? Her wig is crooked, her cheeks hollow with exhaustion. Her daughter dies, her husband dies. She wails, tears her dress, throws dirt in their graves. She sits shiva.

Do relatives support the family afterward? Is she bitter? Resigned? My father merely sketches her existence, praising her and hinting at her frustration. She sacrificed for her children, made delicious barley soup, and never complained to God. She hit him over the head, twisted his nose, and pulled his ears.

§

The original Sierpc Memorial Book was published in 1959. Did my parents get a copy right away? Did Daddy read the necrology? Perhaps he didn’t have a copy at all and this is my stepfather’s book.

Perhaps, perhaps — with a secretive father it’s always perhaps. I reason, imagine, track probabilities. Did he ever know his brother had a wife and child? Did he know he died? I’m grateful for proof, but I don’t deserve it, don’t deserve the knowledge and closure that belonged to him.

I feel lonely.

Whether or not the book was an impetus, in 1959 my parents finally traveled to Israel to see Necha. A reunion after thirty-five years. Daddy’s only surviving sister, Mama’s childhood friend and classmate. Ultra Orthodox, with a devout husband and devout twelve-year-old son. It was an immersion in family, in Sierpc, in cousins and their children, in an old way of life. A joyous time, though Mama worried about him, so tired and pale.

Two years later a simmering cancer erupted. If we could talk about survivor’s guilt, I thought, the tumor would shrink. He died in 1962.

When my grandfather, Reb Yankel, went into hospital with typhus, a nurse gave the beloved shoichet a “lucky” bed in which a teenager recovered. The teenager was Leon, who, thanks to the Sierpc grapevine, became my stepfather. Leon loved history; his heart belonged to Sierpc. He helped gather material for the memorial book and wrote a chapter on relief work. We would sit on the couch, leafing through the book; he showed me photos of his family and told stories.

Mama would shout, “So who needs stories about Sierpc!”

§

I dream I’m in a warm, smoke-filled bar, about to play a peg-board gong, a resonant wooden bowl connected to a rectangular glass box the size of a fish tank. Inside two small, fierce lions face each other — nose to nose, teeth bared, ears erect, tails over their backs. I tap the bowl with my mallet, making the lions fight. Suddenly, in a freak accident, they escape through a slot, gripping each other with their teeth and land, life-size, at my feet. They growl, swishing their tails. People panic. I flee, screaming, “I released the horror!”

Many years later, walking through a 2000-year-old catacomb in the Beit She’arim necropolis, I saw two lions on a sarcophagus — nose to nose, teeth bared, ears erect, tails over their backs. Panic-stricken, I fled, glimpsing, down an infinite time tunnel, an ancient white-robed mason with mallet and chisel, carving my dream.

I paced outside, Jung’s collective unconscious circling like a vulture, pecking at my sense of self. I bought a green-tinged picture postcard. The Lion Sarcophagus, it said, a mythological Greek image on a Hebrew tomb.

Pasted over my desk, the image lost its charge. Stylized ribs and mane, protruding tongues — the lions seemed more friendly than fierce. I described them to a scholar of funerary images. Your lions are guardians of entrances and exits, he said, commonly found on doorways and tombstones.

The dream’s date? Four months after my father’s death.

Orderly design in the universe, my friend said. The lions began to appear, face-to-face on Assyrian lintels in the Metropolitan Museum, in photos of Hebrew cemeteries, on a Polish Passover plate. My lions, my friends. Protecting and mourning, welcoming me to a vast and strange community of dreamers.

Now I welcome my place in Sierpc. The memorial book is both oracle and mausoleum; here my kings and queens lie on stone coffins, newly excavated. I may still be inventing history, but it’s a different history, less haloed than my father’s and less prickly than my mother’s. Writers travel backwards; I have been traveling for many years and the memorial book takes me further and deeper. My father’s ancestors continue to emerge; my mother’s remain buried — my maternal great-aunt, the wigmaker, and my great-grandfather, the pious proofreader, resting in a few stories, their bones protected by universal guardians of entrances and exits.

Quotations from Memorial Book of Sierpc, Poland used with permission of JewishGen, Inc.