In his book Du mode d’existence des objets techniques [On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects] (1958), the French philosopher Gilbert Simondon refers to “key points” — objects at once technical and aesthetic — structuring the territory, such as a bridge, a lighthouse, a castle, a ruin, an antenna.1 Such monuments are also “equipment,” in the modern sense of the word.2 These engineered structures create key points anchored in the landscape. In the volume mentioned, Simondon shows that a new reticulation is favored by technique, instituting a privilege to be granted to certain places in the world, in a synergetic alliance of technical schemes and natural powers: “There, the aesthetic impression appears, in this accord and this surpassing of technique,” inserting itself into and linking “to the world through the most noteworthy key points.”3

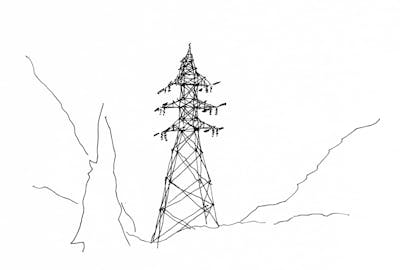

Since antiquity, what constitutes the ground — such as natural landmarks, trees, rocks, mountains, grottoes — has become cultural figures, magical and/or religious, capable of giving a meaning to the landscape.4 Figures and grounds develop a relationship of mutual tension, creating an unprecedented reticulation of the territory.5 In that way, a work of art participates in a networking of the world through its insertion in a region, a town, or a site that thus becomes distinctive: “It is indeed the insertion that defines the aesthetic object, […] the work of art defines the highest point of a promontory, ends the barrier wall, surmounts a tower.”6 In the world, there are remarkable places, exceptional points that stimulate aesthetic creation: “thus, the aesthetic work makes the universe come into bloom, extends it, constituting a network of works, that is to say a network of exceptional realities, radiating, a network of key points in a universe at once human and natural.”7 The aesthetic impression is linked to the insertion in the environment; it is like a gesture that fits itself into the natural milieu, like the sail of a ship under the force of the wind: “the lighthouse by the edge of the reef overlooking the sea is beautiful, because it is inserted on a key point of the geographic and human world.”8 A technical object such as this leads to a redefinition of the relationship between figure and ground: “the object is beautiful when it has met a ground that suits it, of which it can be the proper figure, that is to say when it rounds off and express the world.”9 For Simondon, the technical object acquires its aesthetic capacities against a vaster reality that is used as a ground.

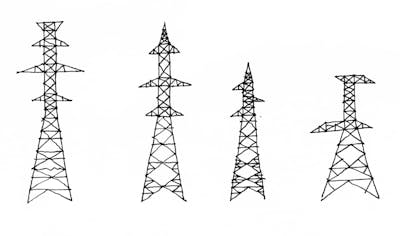

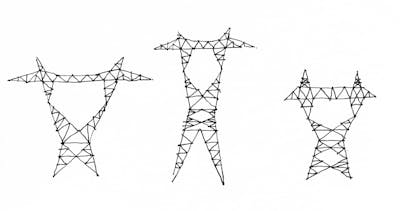

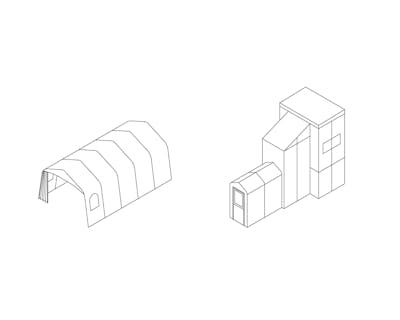

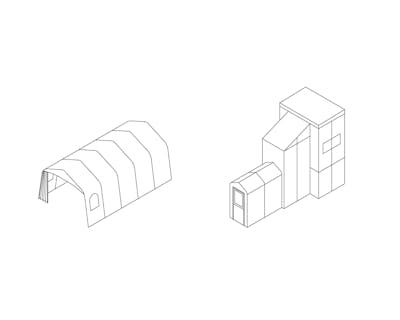

As, in a way, energetic transit points, these key points confer an aesthetic sense to topography. Constituting a network of works, such points are placed right in the middle, in between things; they form a “mi-lieu” [literally, a “mid-place”], which explains the beauty of power line towers crossing a valley.10 The technical object is beautiful when it is the fruit of a meeting between the ground and the figure. An oil refinery, a hydroelectric power plant, a telephone exchange (objects that are oh so forbidding!) are located at the criss-crossing of circuits and, consequently, they can be beautiful, for the lights which come on express aspects of human life, making explicit an unsatisfied desire, an imminent piece of news, a renewed hope.11 The techno-aesthetic objects express affect and percept, and it is conceivable that Gilles Deleuze made Simondon’s thesis his aesthetic and philosophical bible. The examples presented by Bertrand Rougier have value at once local and global: power lines and pylons cutting across forests, temporary snow shelters, nomadic fishing cabins on frozen lakes.They provide the necessary paradigm, which allows the tracing of a new architectural cartography, illustrating the key points in our contemporary world, the age of the techno-industrial and techno-scientific development. Without nostalgia, they redefine also the notion of “nature,” extracting it out of its picturesque or romantic substrate.12

There is a theoretical question, raised by Simondon, that deserves careful consideration. A major portion of Simondon’s magisterial demonstration is based on the concept of analogy, because his aesthetic thinking maintains figure and ground together in an analogical relationship.13 For Simondon, the analogy consists of the identity of the relation between figural structures and a ground of reality. It is the identity of the coupling of the figure and the ground. Such a relationship of analogy offers a guarantee to the unity of the aesthetic work. Forming a complete universe, this relationship creates true monads in the Leibnizian sense of the word.14 What creates the conditions for beauty is not an isolated object, such as a statue, but the association between a real aspect of the world and a human gesture. For example, it is the combination of the landscape and the villa that is beautiful, not the statues of the garden taken separately.15 It is because of the garden (ground) that the statue (figure) can appear to be beautiful. Thus, another paradigm: lines would not be harmonious if they were purely relational.16 With all due respect to Matila Ghyka’s golden number and Le Corbusier’s modulor, beauty is not shaped by number and measure per se. In fact, notes Simondon, a certain curve can be beautiful even when it is difficult to determine its mathematical formula. Simondon’s argument is still valid and has not aged. Besides, there is in it a truth that the painter Eugène Delacroix knew well: “There are lines that are monsters: the straight line, the regular serpentine, above all two parallel lines. When man establishes them, the elements wear them away. Mosses, accidents break the straight lines of his monuments. A line alone has no meaning; it will need a second one to give it some expression. Great law. Example: in musical harmonies, a note has no expression, two together form a whole, express an idea.”17

When all is said and done, it is necessary to come back to the question of the relations between form and matter, at the root of the Simondonian notion of force, then to introduce the concepts of form and information, which allow one to develop and explain the process of “modulation” as laid out in a masterful way in Simondon’s main thesis about individuation (1958).18Then, again, as sketched out in the late text by Simondon, entitled “Sur la techno-esthétique” [On the techno-aesthetic] and published posthumously, it actually seems that a fruitful path opens up.19 Judging by the nomadic, prosthetic objects presented in Rougier’s photographs, a techno-aesthetic could be deployed.20

All photographs and drawings © Bertrand Rougier. Reproduced with permission.

L'Isle-Verte, Québec

L'Isle-Verte, Québec

L'Isle-Verte, Québec

L'Isle-Verte, Québec

La Baie, Québec

La Baie, Québec

La Baie, Québec

49° 16' 30.5" N 68° 07' 53.2" W

47° 30’ 47.9’’ N 70° 25’ 16.2’’ W

49° 16' 26.6" N 68° 08' 15.3" W

47° 42' 05.7" N 70° 06' 56.4" W

47° 35’ 05.7’’ N 70° 18’ 12.8’’ W

47° 42' 03.6" N 70° 06' 50.1" W

47° 48' 07.3" N 69° 57' 05.8" W

47° 42' 05.4" N 70° 06' 45.4" W

47° 42' 10.4" N 70° 06' 44.0" W

47° 40' 13.3" N 70° 09' 18.7" W

chemin Sainte-Foy, Québec City

Avenue du Cardinal Bégin, Québec City

Avenue du Cardinal Bégin, Québec City

chemin Sainte-Foy, Québec City

rue de Longpré, Québec City

boulevard René-Lévesque, Québec City

boulevard René-Lévesque, Québec City

boulevard René-Lévesque, Québec City

boulevard René-Lévesque, Québec City

boulevard René-Lévesque, Québec City

rue de Longpré, Québec City

avenue du Bon air, Québec City

Review

By Robert Mitchell

Georges Teyssot’s “Key Points: Between Figure and Ground” is a wonderful reflection on, and application of, the concept of “key points” that Gilbert Simondon developed in Du mode d’existence des objets techniques [On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects] (1958), and it makes one rue once again the lack to date of standard English translations of Simondon’s major texts. As Teyssot notes, modern key points are for Simondon “objects at once technical and aesthetic” which, because they structure a territory, cannot be separated from the physical space in which they have been placed. (Or, at any rate, these objects no longer function as key points if they are removed from this space.) With that said, the key points that Teyssot exemplifies with objects such as “a bridge, a lighthouse, a castle, a ruin, an antenna” are perhaps better qualified as modern key points, for earlier in his text, Simondon had used the concept to describe the structure of the “magical” world in which humans lived before they made a distinction between religion and technology. The key points of the magical world included spaces of inflection and crossing, such as a mountain peak or the heart of a forest, and enabled a “reticulation of space and time which highlights privileged spaces and moments, as if all of man’s power of acting and all of the capacity of the world to influence man was concentrated in these spots and these moments.”21 Simondon’s descriptions of both magical and modern key points underscore his sense that humans relate practically and affectively to space as a medium that is fundamentally heterogeneous and structured by gradients of attraction and repulsion.

Though Simondon’s account of magical key points was intended to describe a world now long past, Teyssot’s reading — and Betrand Rougier’s striking pictures — helps us consider ways in which scientific knowledge about global ecological processes has facilitated the emergence of new key points that are neither magical, in Simondon’s sense, nor precisely technical/aesthetic objects of the sort exemplified by Teyssot and Rougier. I have in mind spaces such as the ice packs of the North Pole and Antarctic, the Amazon rain forest, and natural parks such as Yellowstone, the managers of which seek to maintain “wild” herds of animals. The beauty of such places is at this point inseparable from the scientific knowledge that positions them as key points within global ecological processes, yet these are not technical objects in the sense of bridges, lighthouses, and castles (if only because their practical power and “use” requires that they not be used in the mode of technical objects). Nevertheless, acknowledging these spaces as key points would be vital for what Teyssot describes as the project of “tracing […] a new architectural cartography, illustrating the key points in our contemporary world, the age of the techno-industrial and techno-scientific development,” and understanding their beauty and appeal would help us to further the innovative aesthetic theory developed by Simondon and taken up here by Teyssot.

Notes

1

Gilbert Simondon, Du mode d’existence des objets techniques [On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects] (1958), (Paris, France: Aubier, 1989), p. 181. As a doctoral student in France, Simondon was required to submit two dissertations, both of which he defended and submitted in 1958. His main thesis, L’individuation à la lumière des notions de Forme et d’Information [Individuation in the light of the notions of Form and Information] was published in two parts, one in 1964 (Presses universitaires de France, Paris) and the other in 1989 (Aubier, Paris), and all together in 2005 (Editions Jérôme Millon, Grenoble). His minor or supplemental thesis, Du mode d’existence, was published in French in the year he defended it (Aubier, 1958) and eventually in German and Spanish editions but not in English. In 1980, part I of Du monde d’existence was translated into English by Ninian Mellamphy, then a faculty member in English literature at the University of Western Ontario, but that text remained in manuscript form. The translations here are those of Alexandre Champagne.

2

The modern sense refers here to Michel Foucault’s notion of “equipment,” which is now accepted in English usage.

3

Simondon, Du mode d’existence, p. 181: “Là apparaît l’impression esthétique, dans cet accord et ce dépassement de la technique”; “au monde par les points-clés les plus remarquables.”

4

Ibid., p. 182.

5

Ibid.

6

Ibid., pp. 183 – 184.

7

Ibid.

8

Ibid., p. 185.

9

Ibid.

10

Ibid.

11

Ibid., pp. 186 – 87.

12

Georges Teyssot, “On ‘that word, Nature’,” in The Avery Review 1 [online], Columbia University, Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, New York, NY, September 2014. http://www.averyreview.com/issues/1/on-that-word-nature

13

Simondon, Du mode d’existence, p. 189.

14

Ibid., p. 190.

15

Ibid., p. 191.

16

Ibid.

17

Eugène Delacroix, “Notes sur les lignes (…),” 1843⁄1849, in Id., Journal, nouvelle édition Intégrale, ed. Michèle Hannoosh (Paris, France: J. Corti, 2009), vol. II, p. 1600.

18

Gilbert Simondon, L’individuation à la lumière des notions de forme et d’information (1958) (Grenoble, Switzerland: Jérôme Millon, 2005, 2013).

19

Gilbert Simondon, “Sur la techno-esthétique et Réflexions préalables à une refonte de l’enseignement,” in Les papiers du collège international de philosophie, CIPH, no. 12 (1992); reprinted as Gilbert Simondon, “Réflexions sur la techno-esthétique” (1982), in Id., Sur la technique, 1953 – 1983 (Paris, France: Presses Universitaires de France, 2013), pp. 379 – 396.

20

Georges Teyssot, A Topology of Everyday Constellations (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2013) ; French edition, Une topologie du quotidien (Lausanne, Switzerland: PPUR: Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes, in preparation, 2016).

21

Simondon, Du mode d’existence des objets technique, édition augmentée d’une préface (Paris, France: Aubier, 2001), p. 164. Translation by Robert Mitchell.

- Tags

- landscapeplaceobjectstechnology

Biographies

Georges Teyssot is a Professor in the School of Architecture at the Université Laval in Québec City, Canada. He has also taught history and theory of architecture at the Istituto Universitario di Architettura (IUAV) in Venice, Italy, the Princeton School of Architecture, and the Department of Architecture at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, Switzerland. Teyssot is the author of many books, including Paesaggio d interni/Interior Landscape (Electa/Rizzoli, 1987), Die Krankheit des Domizils: Wohnen und Wohnbau, 1800 – 1930 (F. Vieweg, 1989), A Topology of Everyday Constellations (The MIT Press, 2013), and Walter Benjamin: Les maisons oniriques (Paris: Hermann, 2013). With Monique Mosser, he co-edited The History of Western Gardens, which has appeared in Italian, French, German, and English editions and multiple re-editions. With architects Diller + Scofidio, he co-curated the exhibition The American Lawn: Surface of Everyday Life at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (1998) and edited the corresponding book, The American Lawn (Princeton Architectural Press with the Canadian Centre for Architecture, 1999). He also wrote the introduction to Diller + Scofidio’s monograph Flesh: Architectural Probes (New York : 1995, 2011). Email: georges.teyssot@sympatico.ca

Robert Mitchell is Marcello Lotti Professor of English and Information Science at Duke University, where he is also Director of the Center for Interdisciplinary Studies in Science and Cultural Theory (CISSCT). His research focuses on relationships between literature and the sciences in the Romantic era, as well as contemporary intersections among information technologies, genetics, and commerce, especially as these have been played out in the legal, literary, and artistic spheres. Mitchell is the author of Sympathy and the State in the Romantic Era: Systems, State Finance, and the Shadows of Futurity (Routledge, 2007), Bioart and the Vitality of Media (Univ. of Washington Press, 2010), and Experimental Life: Vitalism in Romantic Science and Literature (Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2013). He is also co-author of Tissue Economies: Blood, Organs and Cell Lines in Late Capitalism (Duke Univ. Press, 2006) and co-editor of Romanticism and Modernity (Routledge, 2011), among many other works. Email: rmitch@duke.edu

Alexandre Champagne is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. After several years as a financial analyst at the Banque de France, Champagne earned a Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) degree at Cornell University. He interned at Peter Walker and Partners (Berkeley, CA) and worked briefly at Michel Desvigne Paysagiste (Paris, France) before co-founding the firm Aire d’essai (Los Angeles, CA) in 2004. At the University of Illinois, Champagne’s work focuses on history and theory of landscape architecture in relation to dance and movement. Email: champag2@illinois.edu