I

Like the young goat that gives the Caprichos their name, these etchings, unpredictable as goats leaping from boulder to boulder among the hills, evoke the painter Francisco Goya who made them after a sudden illness. At the height of his fame, he falls into a coma, close to death. The doctors have no diagnosis. He fights his way back and comes to himself, forty-six years old, deaf, ridden by the weight of things. His etchings unveil a prophetic vision, a loneliness like no other, and when they become known years after Goya’s death — timeless.

II

Court painter to King Carlos IV, Goya is nursed back to health by a wealthy friend. Enemies at court spread rumors … expected not to survive. At least, he’ll never paint again, they say. He ridicules them as soon as he can pick up a brush, paints small canvases, like a jeweler’s uncut stones, reflections of the nightmare he has lived through, and the inner world his passion unveils, a dark core in which the aboriginal being is close to extinction. “Cabinet” paintings of real disasters; exact details for those who have eyes to see: a shipwreck, bodies washed ashore; a picador impaled on a bull’s horn like meat on a spit; a coach waylaid by highwaymen, dead passengers bleeding on the ground; guards in a madhouse murdering their prisoners, the living dead. In these works the painter embraces his isolation, lets his nightmares drive his art. He absorbs the shock of deafness, portrays himself as an Everyman who refuses to be trapped in a failing body. He returns to work, more confident in his gift. The hand does not lie. “There are no rules in painting,” he writes. The liberated eye speaks the truth and “makes known what God has created … the imitation of divine nature.”

III

Cabinet paintings and finally a large-scale painting that turns the conventions of the church cupola upside-down. A decorative fresco, portraits of people looking down, real people in the dome looking down at angels at the four corners of the earth. None of them sunless, winged creatures, they’re real young women — vivid as the neighbor’s daughter. Goya lands like a bird in the nest, piano and strings playing in everything he touches; the ends of his fingers playing their rhymes. The cupola is dedicated to Saint Anthony of Padua, a priest who saved his own father by raising a witness from the dead to prove his innocence before the court. The legend drew crowds to hear his sermons, imagining such eloquence can rule the underworld. His church — where the apostles come alive. When Saint Anthony of Padua died children cried in the street.

The cupola shapes Goya’s mortal designs. An illumination without words. The Saint in the clouds needs material things to sanctify, singing praises of the earth below where beauty is born.

IV

Beauty survives, kneaded into the dough of popular legends. Goya paints six small canvases, a comic strip of a rumor repeated at every street corner. A friar carrying his saddle bags begs for alms at a big country house. The inhabitants are locked in a back room, hands tied behind their backs by a bandit whose single-handed daring is legendary. The friar at the door, looking the bandit in the eye, grabs his musket with both hands. Hardened by a beggar’s outdoor life, he wrests the gun out of the bandit’s hands and shoots him in the butt with his own gun. “Ah father,” says the bandit, “who would have thought you would betray me thus?…” “Alas amigo, though I showed humility on the outside, on the inside I possessed all the anger of God.” The criminal on the ground, hands tied behind his back, awaits the hangman’s noose. A hero story in tune with the times. The innocent triumph. Good overcomes evil.

V

His world upside-down, Goya’s engravings of mules riding on the backs of the poor tell the story of a kingdom weighed down by its afterbirth, dragging a primal mulishness on the ground. The blindness of the aristocracy as the empire rots under their feet. Eyes are deaf, minds are blind. The court painter sees it from both sides. By the light of the popular imagination, he hears ghosts in back alleys, Gothic romances, haunted mansions. Goya in the light of reason says witches, hobgoblins, boastful giants don’t scare him; he shudders at the enterprise of human malevolence. A grizzled witch rides with a young follower, half rotten before her time, the two as one, double-mounted on a broom by bat-light. Fear rules the night. A broom in the dark kitchen corner shifts behind your back. Farmyard animals wag bloated snouts as the shadows lengthen. Goya paints a giant Billy-goat leading a dance of worshippers. Male witches fly overhead, devouring the living flesh of a male offering — vampire witches feasting on blood. He writes a friend with double-edged venom, “witches are as real as cats.” Violence stains the streets where toughs protect their honor with the sword, and the weak hope to pass unnoticed. Witches as real as cats — the kingdom reeks with the smell of blood. Goya eyes things in the air he breathes. Ghosts don’t scare him. He fears hold-ups on any country road in broad daylight.

VI

Goya paints for aristocrats who rule over vast estates, a few great families passing down their palaces from generation to generation like feudal kingdoms. He loves hunting and can match the steadiest hands shot for shot. Love of killing birds on the wing creates a bond to the Duke of Osuna. The Duke and Duchess represent the avant garde wing of the Spanish Enlightenment, and the artist is drawn into their orbit. María Josefa de la Soledad, Duchess of Osuna, poses for her portrait. The painter’s magic focuses on an in-depth study of character. She steps right out of the frame, the finest cloths in the world woven into her gown. She wears her family name as the finest ornament of all. The Duchess trusts Goya to paint her with immaculate realism. Face and body are long and thin. The aquiline nose ends in a snub. Her chin is long and dimpled. The expression in her eyes is direct, full of confidence. The artist has not stretched the truth. She is no beauty but unmistakably a great lady.

Goya’s relationship with another great lady verges on the sentimental. The legend of the beautiful young Duchess of Alba is linked in popular lore with the great artist, a social nobody, the pride of the Majo, a man of the people. He keeps a portrait of the Duchess, dressed in black for her husband, hidden in his studio. The widow points imperiously at the ground. In the soil one reads the mystifying inscription, “Only Goya.” When the portrait comes to light after the artist’s death it confirms the legend. Alba’s family pride is a state of oil and water in perpetual motion. She’s known as a law unto herself and likes to appear in public dressed up as a Maja, but the heart of the charade is a pastoral romance, ancient as time.

VII

The Caprichos ring with the need to step outside oneself and prophesy. Extreme taxation killed the villages closest to the soil and left the countryside barren. The artist’s step is lighter than air, his gift like a sun and moon shining within him. He observes the crossroads of the capital; there everything is for sale. A streetwalker peddles her wares on the avenue where passersby take her presence for granted. An old crone, bent halfway to the ground by hunger, tugs at her gown for a few spare coins. The young woman is glancing behind her. Goya scrawls on the etching, “God forgive her: and it was her mother.” An ordinary street scene. Nobody pays any attention. The artist conveys form and meaning by the beauty’s shoes. Some alchemy of his own. Shoes pointed in opposite directions, her thighs ready to spread wide apart. The slightest fraction of an inch marks the difference between one pair of elegant shoes and another. None of the passersby mistake the prostitute for an heiress.

VIII

The artist reverses the still life. Genre painting takes its designs out of nature, conflating the beautiful and the pretty. Goya paints flowers, vegetables, meat, fish with scrupulous realism. Bodies piled up on the butcher’s block, flowers wilting in a vase. In his function as a truth-teller, he etches headless corpses and body parts strung up in a tree, among the countless disasters of war. His gift renews constant surprises. Freedom to paint a wild bird on the butcher’s block, scruffy and stiff with rigor mortis. The same for the human animal. No meaning but the discipline of art and the painter’s knowledge of the body, all its postures and blemishes.

The hand of the past appears in a hard light. Drawings of victims shackled to the wall in imaginary dungeons. A costume drama in a painting of a court in session. The Inquisition in its heyday when a summons to appear often meant a death sentence. Prisoners accused of heresy wear the coroza, a cone-shaped dunce cap. The Lector is reading the charges before the court. The Chief Magistrate on the bench nods, yawning with boredom, since the verdict has been decided in advance. Below him two monks listen intently — functionaries known as “God’s hounds.” A mass of viewers crowd the public benches. An audience of ordinary people beset by buried memories of prisoners shackled to stone walls. Goya draws hundreds of sketches, warnings of past and future violence in the Kingdom.

IX

The etchings backed by a multitude of sketches compose vision-essays, declaring radical outrage. An illustration remembers the past when women were convicted of heresy “for having been born elsewhere,” and thousands of Protestants, refusing to renounce their faith, died at the stake. Multi-leveled works of art, sounding voices whose protest endures. The artist uses other faculties, sensuality sharpened by deafness, vibrations unknown to others. The merciless bells of the Inquisition are echoing. Starvation in war-time, a woman in the city, despairing, becomes a nun. Taxation wasting the villages. A peasant unable to feed his family drops his hoe on the ground and looks up to heaven. Goya writes, “crying will get you nowhere.” A woman and child are kidnapped on a country road by a man with a knife. “God save us from such a fate.” Killing blends into the natural landscape. In Los Disparates, “the Follies,” an experienced swordsman is pitted against a younger foe. Each instinctively gathers all his forces —“A Duel to the Death” — the elder’s cunning versus the youth’s speedier reflexes. A sudden moment before the remains of the day.

X

Letting go, he holds on. The wind carries him back in time He rebuilds, replacing shingles on a roof. Sees down through the basement floor and holds on to the gift. His hand imposes its own bottom line. He follows his calling — finds the courage not to curse beauty in the midst of war. Beauty lives side by side with cannibalism. Heroism needs the guillotine. They’re twinned in his mind.

XI

Napoleon comes into the country to aid the failing Spanish King, but when the French squadrons are in position the Emperor shows his real intentions. He makes his older brother the new King of Spain. A guerrilla war engulfs the nation for six years. Goya helps shape an atmosphere, turning the Peninsular War into a national epic. He paints a human “Colossus,” a giant emanation rising from the Spanish soil. On the plain below him, tiny painted figures scurry in all directions. The crusade spreads while Spanish troops are still fighting the invading army. In the people’s war mothers defend their children with kitchen knives and home-made truncheons. Goya’s etchings in “The Disasters of War” are too real to be shown in public — urgent bulletins he keeps to himself, things he saw or heard on the grape-vine about human animals, truths more savage than anything he could invent.

XII

A public record appears in his paintings. Guerilla fighters in the woods prepare to ambush mounted soldiers, then merge back into their villages, an entirely new design, underground resistance. In the countryside a woman carries her water jug to the Spanish troops still fighting. A village blacksmith, the sparks flying from his forge, hammers out the future. An itinerant knife grinder carries the inexorable rotation of his wheel from village to village, a peasant defying Napoleon’s blood hounds.

Goya doesn’t believe battle ennobles. It’s a patriotic myth to snare young recruits. He confesses himself capable of the same sins. We are all wild animals. Killing is embedded in the human psyche. The torsos without limbs, the severed heads hanging on a tree wear no uniforms. An artist for all occasions, he has a warning for colonial empires. An oracle whose time has not yet come. Deafness adds other courses. Goya the artist stays above the battle and conceives epic canvases. An indifferent fire. The gods within realize their own existence. All the senses heightened by terror. Napoleon’s Mamelukes, wearing white turbans, halos of a foreign legion killing everyone in their way, mercenaries stamping out ants. The artist’s faith calls him as a witness. Truth and beauty roll along, sunspots generating solar winds. Empires rot on the ground. The sky unfurls wings of darkness over Spain.

XIII

Beyond the “Disasters of War,” Goya paints big canvases of the rebellion on the 2nd and 3rd of May 1808. The first painting captures the frenzy of battle by imitating chaos. Formal formlessness. Fury and revenge in battle concealing none of the excesses.

The painter honors life itself in the 3rd of May canvas. An impersonal firing squad executes a peasant with his arms spread high, glaring and defiant, the dead piled on the ground around him, an unknown Christ on the cross. Goya designs a painting cooked in a new way that looks raw. The composition makes an indelible impression. A scene that provides details an eye-witness might remember, neither too many nor too few. A synthesis of all-encompassing reality. Everything in the world is on fire. The material world is on fire: the tame and the wild in a bull fight; the bloody spikes. The crucifixion is on fire.

XIV

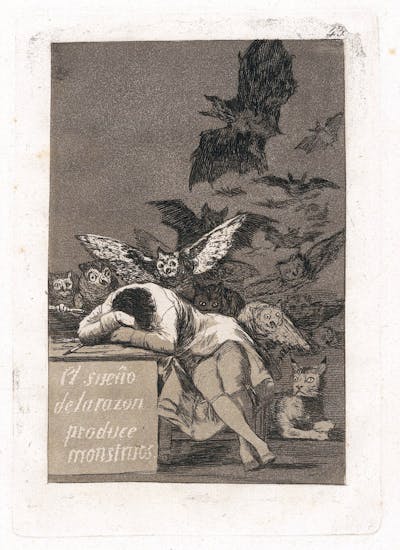

Goya realizes his own dark core of loneliness, the living dead in the underworld. A key Capricho says “The sleep of reason produces monsters.” The animals in the etching — bats, owls, lynx — appear as symbols and images. A man of the Enlightenment, Goya emphasizes the balance between nightmares and waking in the light of day, everything starkly highlighted in this most backward of empires, the painter backlit and lapped by fantasies, myths, as his art takes fire. The complexities of fable and reality spinning like a top.

The romance of the genius Goya and the beautiful young Duchess of Alba takes root in the earth. Gone to a distant country in France, sight failing, the painter effaces himself. “All I’ve got left is will.” He is an instrument, sketching miniatures. An old man on a swing, his horny feet pumping high in the air, lips in a crazy grin. A legless beggar riding on a cart, undaunted, mouth open in an “o.” A burly dancer called Fire spreading his arms, stubby fingers high in the air over no-man’s‑land.