Review

By David L. Hays

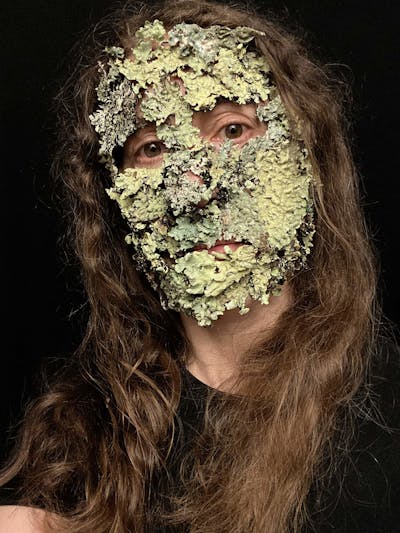

Since the late 1960s, ecological approaches to art and design have placed humans inside nature, yet most of those still idealize nature as a condition set apart — as, for example, through the idea of environment (literally, surroundings). Artist Madeline Schwartzman’s work is ecological in a more intimate and playful way. In her ongoing practice Face Nature, Schwartzman begins by foraging for natural materials — leaves, flowers, seeds and seedpods, lichen, bark, and more. Those explorations are both visual and haptic. Things are examined, disassembled, and assessed. Then, Schwartzman reconfigures elements of interest by attaching them to her face and hands, cladding those otherwise most expressive parts of the body.

In these steps, we see Schwartzman’s natural attachments, both literally and figuratively. The types and qualities of things she finds depend on where she is and when she is there. So, the process of foraging guarantees that the work is place-based and seasonal, even when place and time are otherwise unmarked. From the viewer’s perspective, the power of Face Nature depends in part on recognizing a human body within it, through glimpses of eyes, skin, hair, or the general form of a head or hand. But the medium through which we encounter the work also conditions what we make of it. Seen in still images, Face Nature evokes ornament, costume, and camouflage. It resonates with an eclectic range of precedents — from the ancient Green Man motif; to Arcimboldo’s striking, and arguably comical, vegetal portraits; to the global practice of cosmetics, in which natural materials (and, more recently, synthetic ones) are applied to the face to make it appear either more explicitly artful or more artfully natural. But which of those is this?

Still images of Face Nature are fragile portraits. Clad with transient stuff, the human body peeks out as something vulnerable, like in vanitas images of earlier times. But when Schwartzman moves, live or in videos, the effect is altogether different. She seems to become some other type of being — a non-human animal. The degree to which that impression unsettles us underscores how much our sense of the human still depends on a modern ideal of distance from nature. Intimate knowledge of nature is transformative, even to the enlightened imagination, but, without modern frameworks to make that knowledge seem objective (i.e., distanced), its transformative capacity becomes culturally suspect. Modern logic and its institutions construe people who get too close to nature, blurring conventional boundaries, as variously unnatural, unreal, and unhuman — that is, as the opposite of what they really are: natural, real, and human. And that is where modern ecology falls down.

In keeping with new thinking about ecology, another way to be with Face Nature is to practice it yourself, becoming the body within it. Indeed, Schwartzman guides others into Face Nature through workshops and university courses, like how composer and musician Pauline Oliveros introduced others to deep listening. The message is, do try this at home — or, rather, outside your home. Just be careful in your choice of adhesives. It may feel like strange ceremony, or it may feel like play, but connecting with natural materials will allow you to sense how those elements connect with natural phenomena — solar radiation, wind, precipitation, and fauna — and that will expand your own sensitivity, taking you beyond yourself. Try this wherever you are, pay attention to how it feels, and ask yourself questions. Practicing Face Nature challenges our sense of distance from nature. What might that mean for you? What kind of human will you be if you connect to nature in that way? What is at risk, and what might be gained?

Biographies

Madeline Schwartzman is a New York City-based writer, filmmaker, and architect whose work explores human narratives and the human sensorium through social art, book writing, curating and experimental video making. Her book See Yourself Sensing: Redefining Human Perception (Black Dog Publishing, 2011) is a collection of futuristic proposals for the body and the senses. See Yourself X: Human Futures Expanded (Black Dog Press, 2018) focuses on the human head — presenting an array of conceptual and constructed ideas for how we might physically extend the head, mind, and brain into space. Schwartzman is a long-term faculty member at Barnard College, Columbia University, and at Parsons: the New School for Design.

Website: www.madelineschwartzman.com

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/seeyourselfsensing/

Email: info@madelineschwartzman.com

David L. Hays is co-editor of Forty-Five, co-director of the gallery Space p11, founding principal of Analog Media Lab, and Professor and Brenton H. and Jean B. Wadsworth Head of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Trained in architecture and history of art, his scholarly research explores contemporary landscape theory and practice, the history of garden and landscape design in early modern Europe, interfaces between architecture and landscape, and pedagogies of history and design. Hays is the editor of Landscape within Architecture (2004) and (Non-)Essential Knowledge for (New) Architecture (2013), both by 306090/Princeton Architectural Press. His essays have appeared in a wide range of international design- and history-based journals and as chapters in numerous books.

Email: dlhays@forty-five.com