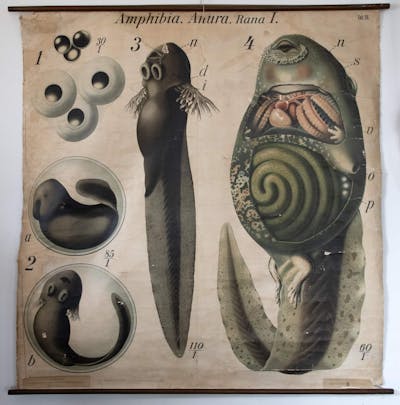

I stare at the frog eggs floating above my head, looming large. They hang on a yellowing and torn chart from the 1930s that illustrates biologically ideal Rana embryos.1 The frogs start out as shiny black pencil dots in white spheres that are perfectly still. Almost featureless and yet very much full of shape, these early embryos quickly develop a sense of front-to-back. They grow towards a fulfillment that eventually allows them to break the glassy membrane and trade an existence of floating for one of swimming free.

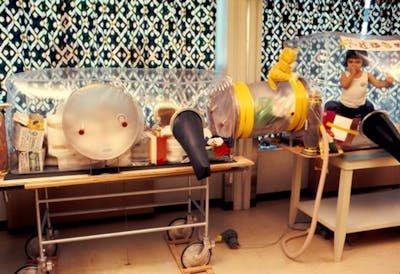

David Vetter, in his bubble.

Source: The Baylor College of Medicine Archives

An educational chart of frog development. Salvaged from Duke University, it now hangs above my bed.

Paul Pfurtscheller, Kaulquappe, tadpole, Amphibia Anura, published by Martinus Nijhoff, circa 1930s.

Whenever I look at these quiet, gelatinous globes and the life growing inside of them, I can’t help but think of the boy in the bubble. When I was young, that boy, David Vetter, was also young. In fact, we were practically the same age. I have personal memories of David, although I didn’t know him personally. I had gathered them from the curved glassy surface of a television; they are memories of footage of David wearing a space suit with tubes stretching behind him like the tentacles of a giant squid. Those images are confusingly mixed with other vivid ones of David. Or not David, but Tod. Tod is a character played by John Travolta in the TV movie The Boy in the Plastic Bubble based loosely and plasticly on David’s life.2

I grew up in a generation of so-called “latchkey kids” who were nannied by television while both parents were away at work. TV was often called the ”boob tube” then not only for its ability to feed children like myself a steady and sedative diet of images, but also because of its potential to turn viewers like me into a boob—70s vernacular for idiot, which my older brother never tired of using in place of my name. Idiocy or not, I am sure I was not alone among kids my age for confusing real people and actors for each other. What made that particular conflation so easy was the fact that the real boy, David, and the fictional character, Tod, were contemporaneous. In the age before reality television, producers opted instead for doppelgängers: while Tod in The Boy in the Plastic Bubble debuted in living rooms across the country in 1976, David Vetter was in fact living enclosed within an authentic, germ-free bubble down in Texas. Hence, they were both different versions of the same character in what felt to me like a common story.

Young David in his bubble, attended by his doctor, Raphael Wilson.

Source: The Baylor College of Medicine Archives

Both David and Tod were born with severe combined immune deficiency syndrome (SCIDS), a genetic disorder that leaves a person without a functioning immune system. Because of this, both boys lived in isolation from all physical contact with others. Without immune systems, their biological identities were at unremitting risk because their bodies had no tacit sense of how to distinguish Self from Non-Self in any somatic sense — a problem, perhaps, of all doppelgängers. David and Tod could be completely overcome by the most banal infection that the rest of us might hardly notice. A common cold was a deadly disease.

Doctors had planned early on to carry out a stem cell transplant to seed a new and healthy immune system in David, but no one in his family was an exact enough cellular match. The bubble, initially conceived as a temporary measure, became an indefinite one. For years to come, David was to remain isolated in this way by millimeters of clear plastic. His parents had to resort to cuddling him with long neoprene gloves built into the wall of the bubble room.

An early version of David Vetter’s multi-room plastic bubble habitat.

Source: The Baylor College of Medicine Archives

In the TV version, Tod’s bubble grows as he does in a kind of architectural metamorphosis. By the time Tod is a teenager, his inner space expands from a custom preemie incubator into a multi-functional room complete with disco lights. It is a lot like a 70s downstairs rec room, but totally transparent. The door doesn’t have the stereotypical handwritten sign that reads “Stay Out!” that TV narratives insisted upon for all adolescent characters. That said, even though Tod’s room is see-through, it is equally clear that it is a membrane designed to keep everything on the outside. They feed Tod in the movie, although it is not clear how. On the other side of another membrane, down in Texas, anything that enters the reality of David Vetter’s bubble is carefully sterilized with peracetic acid and moved through a system of steel capsules and air locks.3

Tod watching over his hamsters.

Sourced from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=adZy4wM2Jg0

Although the signs of a normal boyhood are there in his décor and his jokes, Travolta’s Tod does seem to float in his own jelly-like world — naïve and frustrated, well-protected and yet constantly at risk of peril from the world beyond. The pet hamster in a plastic cage is the improbably unsanitary prop placed in Tod’s bubble room, intended to provide the viewer visual metaphor for his confined condition. He grows up watching the other kids play by the lake out the window. People call him the “bubble boy,” and there is no denying it: he seems heavy and weightless at the same time, easily popped if poked, a quintessential and yet otherworldly adolescent.

Of the manifold membranes found in nature, none serve to isolate completely; rather, the role of membranes is to mediate. For a developing tadpole, the permeability of the surrounding membrane allows for the passage of oxygen and other essential molecules. For someone like Tod, whose whole life seems at the mercy of everything else, the regular use of an intercom makes perfect sense as a way to make the membrane more permeable. Even though sound travels well enough through the thin clear plastic, the intercom is a means for him to maintain some small measure of control over the exchange between his fortified world and the larger one he is suspended in.

John Travolta’s “Tod” enjoying some time outside while inside in the film The Boy in the Plastic Bubble (1976).

Sourced from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=adZy4wM2Jg0

Still, the bubblecraft remains difficult to navigate. Halfway through the film, someone comes for a visit who might help address this issue: the second man ever to walk on the moon, Buzz Aldrin (the real Buzz Aldrin!), visits Tod. Aldrin shakes his hand and says, “You know I‘ve been looking forward to meeting you. I hear you have the record for the longest time in a command module.” Aldrin hands him an odd souvenir — a piece of paper from NASA that reads, “To Tod, champion spaceman on earth.”

Given that Tod, né Travolta, builds models of the Saturn V rockets that carried astronauts like Aldrin to space, the sentiment follows a fairly patronizing kind of logic. However, given that NASA scientists not only helped design the hermetic bubble in which David Vetter actually lived, but also created the squidy spacesuit that he wore outdoors, in the world, this scene would appear to be a meaningful cinematic nod to the true story of the real boy. However, like so many other things in the film, it ends up being a strange projection into David’s undetermined future; for while Tod debuts a spacesuit in the movie in 1976, David doesn’t actually get a chance to wear one until 1977.4 With parallel universes can come time travel, and we observe the fictional boy’s televised experiences preempting David’s lived ones by over a year. Tod even goes to high school in his suit. He walks around in this outer space on Earth with his new friends, and they sit in a circle on the football field. “How do you go to the bathroom?” a classmate asks. “Oh, just like the astronauts do,” he somewhat explains. Unlike any astronaut, however, he also alludes to his successful space travel without the suit. “Have you guys ever heard of out-of-body travel?” he asks his new friends on the football field. “Well, I do it all the time,” he confesses, “lots of different places.”

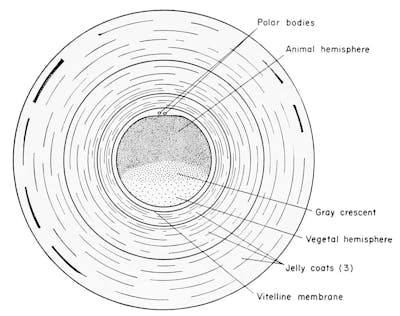

A diagrammatic drawing of a frog egg 35 minutes after fertilization, in the throes of its cortical rotation.

Source: Roberts Rugh, The Frog: Its Reproduction and Development (Philadelphia, PA: The Blakiston Company, 1951), pag. non cit.

Sourced from: https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Book_-_The_Frog_Its_Reproduction_and_Development_4

Frog eggs have traveled to lots of different places, including outer space. If sent into zero gravity Earth orbit, it turns out they develop more or less normally.5 This is despite the fact that, in outer space, the embryos skip cortical rotation, a developmental step that scientists — for the prior 100 years — had assumed was absolutely crucial for tadpole development. More specifically, biologists believed that the gravitational force of our planet typically cues cortical rotation, which turns out to be true, but that apparently has nothing essential to do with the proper formation of the frog. Tadpoles in space develop and emerge from their jelly-eggs just as they do on Earth. The only thing they don’t do in the regular manner is inflate their lungs. “Why didn’t the lungs inflate?” asks NASA researcher Emily R. Morey-Holton. “We don’t know the answers to these questions, but we do know that air bubbles were present in the tadpole aquatic habitat on orbit. Possibly, lack of directional cues or increased surface tension between the air-water interface interfering with penetration of the air bubbles may be involved in this interesting observation.”6

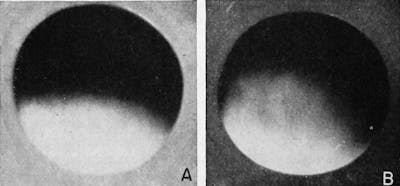

Photographs of a frog egg forming its “grey crescent,” a region that emerges in the embryo because of cortical rotation. This “crescent” will help the seemingly homogenous sphere development an inner organization from which the morphology of the tadpole can start to manifest.

Source: Roberts Rugh, The Frog: Its Reproduction and Development (Philadelphia, PA: The Blakiston Company, 1951), pag. non cit.

Sourced from: https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Book_-_The_Frog_Its_Reproduction_and_Development_4

Interface or interfere. Does a boy raised as a spaceman develop normally? Can he skip seemingly crucial steps and yet still swim free? As seen through the celluloid, it would seem so. Tod’s first kiss occurs across his plastic faceplate and is awkward but touching. If things can touch each other physically through membranes, then it seems they can do so figuratively as well. The girl regrets that Tod didn’t have the spacesuit when he was younger; Tod reflects on the possibility and says a very unspaceman-like thing: “I never dreamed about going out, only people and things coming in.” It is all too clear that Tod is referring to the well-known phenomenon of emotional osmosis. A gradient of feeling existed across the membrane, an action potential that only active diffusion into his bubble/egg/space module could resolve, affirming his selfhood through the non-self. The tender teenage kiss is a narrative rite of passage that allows Tod to develop normally, no matter how many steps he skipped along the way while floating.

It turns out that David eventually saw the Travolta TV movie that fictionalized his life, and it’s hard not to wonder what he thought about his body double in an alternate reality, the one who was acting as if he were trapped inside the bubble when he in fact was safely outside. In the fictionalized version of his own life that David watched on television, Tod falls in love, graduates high school, and — at the end of the film — actually breaches his confines to ride away on the back of a horse with his girlfriend. David, however, increasingly suffered anxiety and emotional outbursts as he got older. Walking out of his house in his spacesuit only seven times in his life, David’s deep fears about germs kept him voluntarily inside. Despite his amazing resilience, the bubble took a profound psychological toll on David, impacting his interactions with caretakers and those who loved him. To him, it must have felt like science fiction, which it was.

David Vetter lived in the bubble that NASA made for him until the age of twelve. In that year, the stem cell transplant for which his family had hoped from the beginning finally took place, but it resulted in an infection that claimed his floating life. Broken free from the bubble and the experiment, the tadpole swims away.

Tod in his terrestrial spacesuit, apprehensive at walking into school for the first time. In the movie, it is Tod, inspired by watching astronauts on spacewalks, who comes up with the idea of the suit.

The Boy in the Plastic Bubble (1976).

Sourced from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=adZy4wM2Jg0

Review

By Sandra Kaji-O’Grady

Yang’s observations about David Vetter and his “doppelgangers” point to the entanglement of medical research and public entertainment. David’s family sold their story to the media to subsidise the costs of his care. Research grants that supported the medical team required broad public support.7 Thus, a solitary boy’s life and early death became a public event, a story that could be retold and performed by others. Retreat to the isolated safety of a sterile bubble was acted out across multiple communities. An epidemic of “chemical injury syndrome” saw sufferers constructing makeshift “bubbles” in cars and caravans with plastic wrap, aluminium foil, rubber gloves, and antiseptic. The inhabited bubble made appearances in music videos for Kate Bush’s song “Breathing” (1980) and Simply Red’s cover of “The Air that I Breathe” (1998). Artist Mori Mariko depicted herself suspended mid-air in a bubble over an alternative reality in her photomedia series “Esoteric Cosmos” (1996−1998). In 2008, Xavier Trillo, inspired by the film “Boy in the Plastic Bubble,” launched a business specialising in “the creation of portable spaces containing pure air.”8 Bubble/Pure Air is todaymarketed to the medical, physical fitness, anti-aging, and cosmetic industries as a portable space “in which it is possible to breathe 99.95% pure air in continuous regeneration — free from contaminating particles and bacteriological and allergenic agents.”9 Bubbles also made their way into leisure and tourism.10 One can be purchased for home as a “self-contained living space for indoor/outdoor use.”11

There is, though, a decisive break in form and function between David’s isolator and the one inhabited by John Travolta’s character or these more recent “doubles.” His was a clunky set of interlinked rectangles weighed down by mechanical plant, tubes, and gloves and contained within another room — the hospital in David’s early years, later the family home. Its genesis lay in the germ-free animal enclosures developed in the 1950s for laboratory research. When plastic replaced rigid materials, isolators retained their boxy form as it allowed efficient stacks and rows. Scientists involved in establishing germ-free strains of rodents for experimentation were keen to add other species “such as dogs, cats, monkeys, goats, sheep, pigs, and cows” believing it “necessary to study the germfree animal species by species, variety by variety, and generation by generation.”12 David presented an opportunity to add humans to this list when he was born — with a high probability of genetically-inherited SCIDS — at Notre Dame Hospital, where Philip Trexler, one of the leading researchers in germ-free animal enclosures, was employed. Fixated on hygiene, little adjustment was made to the design of the isolator to meet the psychological needs of a human child.

The filmic and popular versions of the bubble transform this experimental death chamber into a buoyant, free-floating sphere. The appeal of the floating bubble is that it is a place to exercise/exorcise anxieties about the self and its boundaries that emerge in the wake of new understandings about the immune system. Scientists had come to view diseases such as multiple sclerosis, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis as failures of the immune system to recognize and tolerate the body’s own proteins. The militaristic model of the immune system as insulation against that which is foreign is brought into doubt. Henceforth, the immune system became “an iconic myth object in high-technology culture” (Donna Haraway).13 Jacques Derrida spoke of a “general logic of autoimmunization” at the level of the society,14 and Peter Sloterdijk made the immune system a centre piece of his theorization of a spatialized model of subjectivity, or sphereology.”15 For Sloterdijk, the preoccupation with spheres, from the womb to the globe to the celestial dome, defines our species. He writes, “The sphere is the inner, discovered, shared round shape that men live in as they become humans. Because to reside somewhere always already means to form bubbles … humans are those beings who put up circular worlds and look into horizons … Spheres are spatial creations effective from the point of view of immunology …”16 The creation of a self is the formation of an insulating sphere. No wonder this cosmogonic motif abounds. But, we must inject a historic and economic note to Sloterdijk’s cosmology. The buoyant bubbles of plastic discussed here and in Yang’s essay do not shelter or connect us to place or each other. Like other artefacts and other selves, they are purchased, traded, borrowed and discarded, just as we may purchase and trade breathable air in the future.

Review

By Lydia Kallipoliti

A few days past the US presidential elections of 2016, NBC’s Saturday Night Live [SNL] broadcast an uncanny resemblance between the architecture of utopia and the architecture of media. In the satire, “The Bubble: Established 2017,” Buckminster Fuller and Shoji Sadao’s “Dome Over Manhattan” — an icon of weather and climate control shielding a selected population of New York City from pollution — was transported intact over Brooklyn to illustrate an electronic bubble with social media control to shield progressive Americans. Inside the Brooklyn bubble, the elections have never happened, and the voluntarily contained citizens could live in a liberal world with electric cars, organic products, vegan food, and conversation with other likely-minded individuals; they were reassured that, whilst inside, they would hear nothing but the echo of their own voices. The bubble, therefore, evolved from representing an architectural typology of shelter against pollution and adverse climate, to a virtual object that protects insiders from listening to those voices coming from the outside: those voices that each citizen has excluded from their social media feed, albeit unwittingly. What you would hear inside the bubble were reverberations of the “ego.”

SNL’s bubble is not just a satire. It depicts with acid clarity the social reality of the “echo chamber,” which has been broadly discussed in news media theories as a byproduct of our pervasive use of social media. The term describes an enclosed space of voluntary containment, like a bubble, where the subject deliberately listens to the echo of its own voice. With our digital footprint, the algorithms of Facebook and other social media apps determine a newly formed public space: a space of personalized bubbles, each carefully curated and edited. Our contact with those online citizens, who are either distant or resistant to the game of “liking everything,” is diminished and fades into the darkest sides of data, a black abyss of information that we have marginalized as irrelevant or unwanted. So, each of us receives, and in return transmits, only our own thoughts and thus reconstructs a worldview of the self. The progressive liberals (myself included) enclosed in the Brooklyn bubble are not only emotionally wounded from the election results, but are also in denial. As the journalist Μostafa El-Bermawy observed in Wired magazine (2016), our virtual social dimension has created individual eco-chambers in the form of self-enclosing bubbles that deter encounter with the outside. David Vetter’s frustration with the possibility of breaking the bubble has been reincarnated in a different type of environment: one that is unrelated to physical contact and the anxiety of infection, but very much linked to the idea of breaching the boundary of a safeguarded space. The social bubbles of Facebook and Google have designed for us the reality of our everyday lives, which to some extent is in its own right a violation of collectivity.

In the early 2000s, the architectural typology of the bubble and the dome was silent, if not non-existent, both virtually and physically. The collective visual imagination pivoted on the concept of the network. The writings of Gilles Deleuze, and specifically his multidimensional depictions of the rhizome, offered to an eager audience of young architects the visual analog of the possibility of an interconnected world, a wide, thick mesh of ideas cast over the planet. The structure of the spider web — so beautifully narrated in Mark Wigley’s “Network Fever” (2001) — evidenced ideals of unity, connectivity, and management of planetary networks; it visualized our desire to co-exist connected, simultaneous, and intertwined in geographically distant environments.

What then inspired connectivity, cohesiveness, interactivity, and virtual cohabitation has been replaced by individualized, enclosed bubbles nurtured by ongoing operation of the world wide web. The architecture of digital media is thus the representation of this paradigm shift. Arguably, it is based not singularly on our relationship with media and the forms of disseminating one’s work, but on representation of the space that is produced as a result of our daily practices. Now that global communication is mundane, our sense of satisfaction can be gratified online instantly, physical distance is no longer a limitation, and the web is a vital survival need, each subject has voluntarily secluded the ego into a bubble: the realization of the personal space that is constituted and augmented with each “like.” In this setting of “egospheres,” as Peter Sloterdijk would argue, we are culturally in suspension; up in the air. Each being is vacillating without touching its neighbor or belonging to a collective. The danger of social media is therefore the euphoria of a false sense of democratization based on the quantification of acceptance and the displacement of organizations that truly support social cohesion.

In celebrating this kind of extreme interiority, reinforced by the allure of environmental performance, we are spectators of a new urban experience: the network has given way to the cloud, and the bubble is the incidental by-product of the cloud. The bubble, albeit unwittingly, rises as a control mechanism that detaches us from civic engagement. The bubble also begs a simple question: What is the urban experience in this time of voluntary containment? A new breed of psychogeographic drifters is roaming on their customized itineraries as their phones instruct. In this new territory, where everything is hyper-connected, the subject becomes increasingly contained. Every echo becomes a world.

Our constant experience of being connected yet detached allows us to affirm ourselves by augmenting our containment as something simultaneously interiorizing and exteriorizing. Yet, our new communal existence with public space cannot be based exclusively on mediation of data. As citizens and creative thinkers, we need to think beyond the bubble. As a famous movie line suggests, “open your eyes” to the bubble inside which you are voluntarily contained. Then, develop an erotic yet resistant relationship with your bubble. In that way, it might be possible to penetrate the bubble and imagine other ways of being, even to imagine some real grounds of hope beyond the market commodity of a digitally enhanced euphoria.

Notes

I salvaged this educational chart from the trash at Duke University in the mid-1990s.

The complete movie The Boy in the Plastic Bubble is available for free through the Internet archive, http://www.archive.org/details/The_Boy_In_The_Plastic_Bubble.

Detail from the transcript of the PBS American Experience documentary “The Boy in the Bubble”: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/bubble/.

The spacesuit’s official name was “The Mobile Biological Isolation System.” It had an accompanying 54-page user’s manual.

Kenneth A. Souza, Shaun D. Black, and Richard Joel Wassersug, “Amphibian development in the virtual absence of gravity,” Developmental Biology 92 (March 1995): 1975 – 1978.

Emily R. Morey-Holton, typescript of “The Impact of Gravity on Life,” text eventually published in Evolution on Planet Earth: The Impact of the Physical Environment, eds. Lynn J. Rothschild and Adrian M. Lister (Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Academic Press, 2003). Accessed October 13, 2009, at www.mainsgate.com/spacebio/Sptopics/hy_resource/holton.pdf.

About US $200,000 was granted annually in research grants from the National Institutes of Health (American Medical News 20, 1 (1977): 9 – 11).

“Zonair3D: Our History,” http://www.zonair3d.com/en/zon… (accessed October 14, 2014). Updated link: http://www.zonair3d.com/en/history/.

“Bubble/Pure Air: How it Works,” http://www.zonair3d.com/en/products/bubble-pure-air/ (accessed October 14, 2014).

Consumers can stay overnight in the Bubble Hotel founded in 2010 by Attrap’Rêves in France or the Bubble Lodge in Mauritius: https://www.attrap-reves.com/en/sleep-in-a-bubble-cc/ (accessed October 30, 2014).

Cocoon 1, by the Nordic Society for Invention and Discovery (NSID), is manufactured by Micasa. A similar product by Monica Forster, “Cloud,” is distributed by Offect. See Nordic Invention homepage: http://www.nordicinvention.com/cocoon.html (accessed July 15, 2014).

James Reyniers, “The Pure-culture Concept and Gnotobiotics,” Germfree Vertebrates: Present Status, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 78: 1 (1959): 9.

Donna J. Haraway, “The Biopolitics of Postmodern Bodies: Constitutions of Self in Immune System Discourse,” in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York, NY: Routledge, 1991), 205; Emily Martin, “The End of the Body?,” American Ethnologist 16 (1989): 121 – 140: see p. 126; Roberto Esposito, in Timothy Campbell, “Interview: Roberto Esposito,” trans. Anna Papacone, Diacritics 36 (2006), 49 – 56: see pp 53, 54.

Jacques Derrida, Rogues: Two Essays on Reason, trans. Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas (Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ. Press, 2005), 124.

Peter Sloterdijk, You Must Change Your Life, trans. Wieland Hoban (Cambridge, England: Polity Press, 2013), 449.

Peter Sloterdijk, Spheres. Volume I: Bubbles, Microspherology [Spharen I: Blasen, Editions Suhrkamp Frankfurt, 1998], trans. Wieland Hoban (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2011), 28.

Biographies

Andrew S. Yang is an artist working across the visual arts, the sciences, and history to explore the naturalcultural. His work has been exhibited from Oklahoma to Yokohama, including at the 14th Istanbul Biennial (2015), the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, (2016), the Spencer Museum of Art (2019), and the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History (2020). Yang’s writing and research can be found in Art Journal, Leonardo, Biological Theory, and Antennae. He is an Associate Professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a research associate at the Field Museum of Natural History. In the spring of 2020 he will be the inaugural artist-in-residence at Yale-NUS College in Singapore. www.andrewyang.net. Email: ayang@saic.edu.

Sandra Kaji-O’Grady is Professor of Architecture at the University of Queensland, Australia, where she teaches design. She was the Dean and Head of School at the University of Queensland from 2013 to 2018, and she previously held similar roles at the University of Sydney and the University of Technology, Sydney. Kaji‑O’Grady’s research on the expression of science in laboratory architecture culminated in two recent books: Laboratory Lifestyles: The Construction of Scientific Fictions (MIT Press, 2018), which she co-edited with Chris L. Smith and Russell Hughes, and LabOratory: Speaking of Science and its Architecture (MIT Press, 2019), co-edited with Chris L. Smith. Her essays have appeared in numerous, important journals, including The Journal of Architecture, Journal of Architectural Education, Architecture Theory Review, Architecture Australia, Architectural Review Australia, Artichoke, Object Magazine, and Monument, among others. Kaji‑O’Grady earned B.Arch. and M.Arch. degrees from the University of Western Australia, a graduate diploma in Women’s Studies from Murdoch University, and a Ph.D. in Philosophy at Monash University. Email: sandra@uq.edu.au.

Lydia Kallipoliti, Ph.D., is an architect, engineer, theorist, curator, and educator with degrees from Princeton University and MIT. She is currently an Assistant Professor at The Cooper Union, having taught previously at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, where she directed the MS Program; Syracuse University; and Columbia University. Her work has been exhibited internationally, including at the Oslo Architecture Triennale, the London Design Museum, the Disseny Hub Barcelona, the Istanbul Biennal, the Shenzen Biennale, and Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York City. She is the author of the award-winning book The Architecture of Closed Worlds (Lars Muller, 2018). Email: lydia.ka@gmail.com