Situating Cultural Knowledge

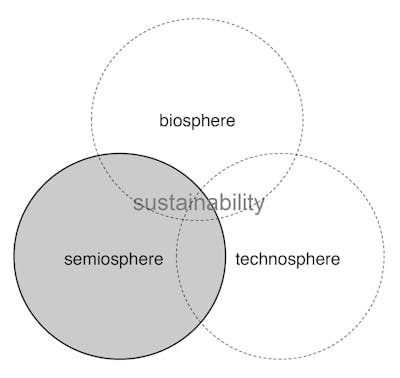

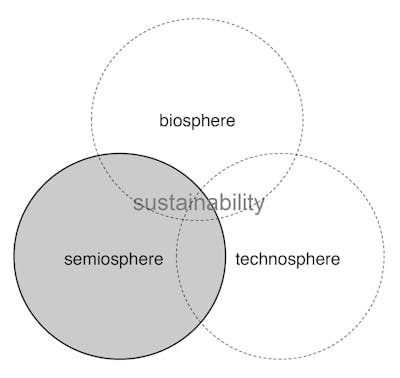

Artists today are seeking greater social engagement, moving beyond entrenched roles circumscribed by the culture industry, towards the compelling issues of our time. Some are evolving knowledge-based platforms for public practice, operating in the larger society to re-imagine knowledge, to create new futures. We began our journey fifteen years ago, encountering the charismatic theorist Tony Fry with his focus on the semiosphere,1 the intangible realm of values and meanings. We understood this as a direct challenge to artists and the culture at large.

Our work since then has been driven by these core questions and a search for creative answers.

• What is Sustainability?

• What is the role of Culture?

• What is the role of the Artist?

• Where is Agency to effect change?

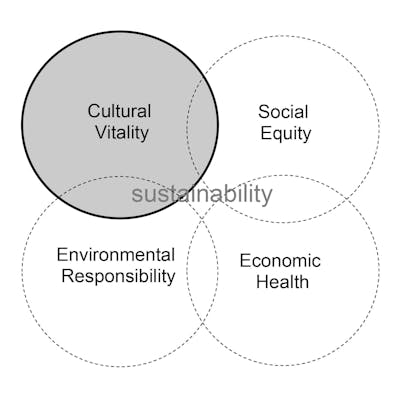

We came to articulate two interconnected cultural hypotheses, which form the basis for subsequent experiments. First, sustainability is a cultural problem and requires a whole-system cultural framework that accounts for intangibles to succeed. Second, artists’ particular expertise can be of great value to trans-disciplinary teams due to largely unexamined skills that contemporary artists deploy. In this way, a new model of cultural praxis has emerged: private questions led to strategies, strategies to initiatives, initiatives to engagements, widening out towards the public realm, the civic experiment. Animating this meta-project is the rhetorical question, “What Do Artists Know?”2 which has over time become both method and message. Although academia addresses art practice within research culture, questions of knowledge and innovation have a different order of urgency for the civic sector, including rust-belt American cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland, where we have found considerable appetite for new ideas.

Tony Fry, 2000. Fry attributes this model to himself with Ezio Manzini and Félix Guattari. Redrawn by the author.

The paradigm shift from industrial to post-industrial, underway it the late 1990s, catapulted urban discourse into a liminal zone of new possibility and urgency. Contested theories of sustainability were emerging from “design thinking” but not “arts thinking.” Within this theory, a post-enlightenment, meta-typology of cultural practice, “artefacture,”3 locates the environmental crisis firmly within artifice, in a non-hierarchical zone of cultural production, art, design, philosophy, science, etc. This focus outside specialization challenges the significance of isolating purely symbolic strategies and has brought the symbolic back into conversation with the practical, offering the potential to, as Janeil Engelstad has said, “make art with purpose.”4 The autonomy of individualistic art practice is augmented, not refuted, creating a space where meaning and purpose coexist, are equally valorized, offering expanded agency to artists and refocusing design practice on ethics and signification. For artists interested in art’s relationship to both the built and natural world, this is a space full of possibility, capturing the imagination, where all disciplines collaboratively constitute an emergent “trans-disciplinary.”

During this same period, the art world has seen a contentious polemic concerning the movement known as social practice. Organized around Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics,5 parties argue the potential of blending the political, the social, and the aesthetic. This discourse is focused primarily on social justice, seeing ecological concerns as a dimension of the “social.” Embracing event-based, collective action, critique, and resistance, or as we could say, “Act UP, Point OUT, Opt OUT,” the “social turn”6 continues to grow, even as it is challenged for its “largely symbolic commitment to politics.”7 As artists with a systemic view, we have inverted these conventional activist art strategies by “opting” IN not OUT, deferring, at least temporarily, the question of “art,” which can limit our ability to re-conceive possibilities. Here we follow the advice of American philosopher John Dewey, who exhorts:

In order to understand the meaning of an artistic product, we have to forget them for a time, to turn aside from them, and have recourse to the ordinary forces and conditions of experience that we do not usually regard as esthetic.8

Performing the Tropological Transdisciplinary

Through OPTing IN, we have learned to speak the languages of other disciplines, both nomenclature and attitude, reflecting multiple intents and values. Cultural geographer Mrill Ingram has called this the “diplomacy of art,”9 a symbolic handshake, reaching outside art practice towards the work of others, to become value-added. This diplomacy sometimes disrupts these practices by operating within their sphere differently. Some would claim “generosity,”10 a joining in, dot connecting. This also disrupts “art.”

Thus, when describing the formulation of recent projects, we often communicate in distinct voices, which inform both the verbal and visual delivery of information, a kind of durational speech act. Here we might utilize an exacting, descriptive, expository voice, especially used for technical details from other disciplines, which we perform factually, faithfully. Also present is a rhetorical, persuasive voice, a voice that makes claims, pronouncements, delivers statements of implication, signification, intention, and aspiration. This is a crucial voice for the cultural for herein lies the debate concerning ideas, actions, and their meanings. Lastly, we employ a poetic voice, a figurative, metaphoric voice sometimes spoken, sometimes purposefully withheld, sometimes represented visually but not paired with verbal equivalents. This is the voice of the trope, the double meaning, ambiguity, the voice of the cultural outside the paradigm of knowledge production, outside certainty. For whatever is said, something else is not said; something else is always meant. This is the underlying logic of these projects even where it is not articulated. This tropological transdisciplinary forms the basis of the Tactics for Praxis.

Practicing in Public — (we know we don’t know)

In each project that follows, there has been an explicit aim and outcome; but in each case, additional unforeseen outcomes have also arrived, which are carried on as a reflexive working method. We are practicing in public — we know we don’t know.

From 2005 to 2007, another artist and I became deeply embedded in the planning process for a new trail and greenway in Cleveland, Ohio, that ran beside the historic steel mill. The explicit outcomes were a systemic sustainability plan for the trail, and a process for including artists in such projects. The sustainability plan included an ambitious technical proposal to change the steel mill, saving CO2 by granulating steel slag, piled up, barely used. This technical possibility grew from the recognition that the slag pile is cultural heritage, not waste, and from understanding it as an underutilized asset available for revaluation. Here we did not invent a new technology. Rather, acting as free agents, not as paid consultants, we ignored the advice of the engineers and did the research required to identify an available technology, maintaining autonomy even in collaboration—artist as a new kind of problems solver.

Over a two-year period, the planners began to note things they perceived we artists knew, and why it was valuable, unintentionally producing a Knowledge Claim for artists. The document articulates the tacit and methodological knowledge deployed by contemporary artists. The most important claims are for a radical lateral-ness and special cultural literacies that arise from being both producers and critics of culture. Additional important aspects deal with the ability to maneuver in multiple economies, transferring and transforming value. With this Knowledge Claim, we were able to engage directly with Fry’s well known “change strategy,” Redirective Practice, which challenges each discipline to redirect from within.

The ambition of redirective practice is to…gather a multiplicity of practices, including, but beyond, design, to start to redesign/redirect the structural and cultural condition that designs our mode of being-in-the-world […].

Redirection does not mean total rupture; rather it means, modifying, remaking or reframing…”11

A systemic look at my own art and life revealed three sectors for redirection—personal, pedagogical, and professional—and produced three redirective projects. Almost immediately, intentions, means, and methods began to transgress the borders, circulating ideas across situations, generating more provocative projects, and unexpected agency. Eventually this transliteration jumped the borders of art practice into architecture and, from there, into the civic arena. Pedagogically, we imported our professional questions as participatory curriculum, creating the Knowledge Lab. We simultaneously exported pedagogy. Next, The Greenhouse Chicago was initially conceived to redirect our private home/studio. However, during construction we became radicalized about the possibilities and transformed the project, taking creative control away from the architect, adding features immoderately, testing the limits, turning it into a demonstration project, BOTH architecture AND art. The studio moved from the site of production to the object produced — the studio became the art. Duchamp in reverse. The other outcomes were more surprising and harder to claim. Though not our intention, our commitment to the actualization of this encyclopedic project challenged architecture. The house became not only the art, but also the classroom, as architects and urbanists came in for tours, creating opportunities for dialogue and future engagement. We were no longer redirecting from within, we had OCCUPIED architecture, performed architectural redirection, a RUPTURE, reversing and up-ending traditional hierarchies and roles. We were simultaneously solving problems and creating them.

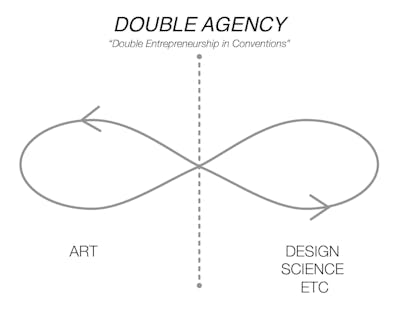

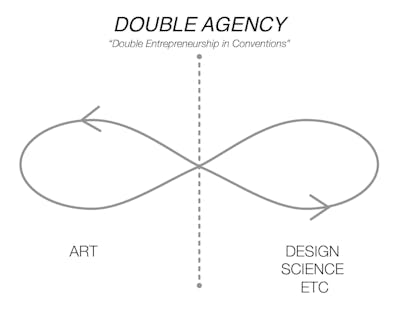

Diagram and Double Agency concept by author, adapted from Sacha Kagan, Art and Sustainability: Connecting Patterns for a Culture of Complexity, Transcripts-Verlag (August 5, 2011).

Artists interested in these new modalities of practice use their disciplinary skills very strategically, deploying another type of knowledge known to the Greeks as metis. In The Practice of Everyday Life, de Certeau describes metis as:

“knowledge that is immersed in practice” combining “flair, sagacity, foresight, intellectual flexibility, deception, resourcefulness, and diverse sorts of cleverness.”12

In the professional realm, complex work is now performed by multi-disciplinary teams. What happens when you add an artist into this system as professional transgressor? Important here is Sacha Kagan’s, notion of “Double Entrepreneurship in Conventions.” To “play on the rules rather than in the rules.”13 Here, the artist is a double agent, putting the transgressive dimension of contemporary art to practical use.

Thus, through metis, artists and other cultural border hoppers are a kind of irreverent cross pollinator, punching holes in disciplinary walls. Operating both inside and outside art, both inside and outside civic and public structures, a kind of double change agency. Again leveraging the Knowledge Claim, we launched the last of the redirective projects, the Embedded Artist Project. Sponsored by Chicago’s Department of Innovation, the program ran between 2008 and 2012. Here, artists are embedded in city workgroups to bring new perspectives to the daily work of the city. A decade after its inception, the legibility and value of this strategy has begun to increase, as other cities in the USA, UK, and New Zealand are adopting embedded artist programs influenced by this model.

Civic Experiments – (praxis)

Slow Cleanup: Sites of Public Learning

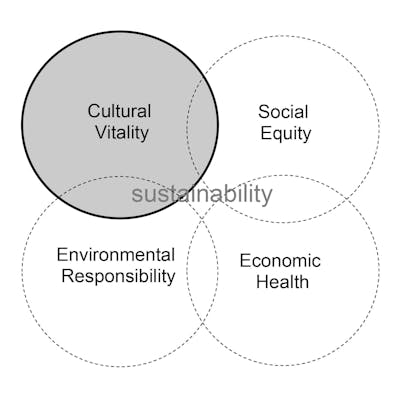

Jon Hawkes, The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability: Culture’s essential role in public planning (Melbourne, Australia: Common Ground Publishing, in association with the Cultural Development Network (Victoria), 2001). Redrawn by the author.

Working as Embedded Artist with the Chicago Department of Environment, we developed Slow Cleanup, a net benefits model for Chicago’s 400+ abandoned gasoline stations, a legacy of American automobile culture. A very informed Commissioner of Environment embraced the proposal to use Jon Hawkes’ Four Pillar14 model as a schema for a new approach to brownfields, using phyto or plant-based remediation. Modeled on the Slow Food movement, the program rejects the “Fast Cheap Easy” paradigm of conventional ”dig and dump” cleanup. Technically, petroleum remediation is performed by soil microbes attracted to phenols, sugar-like substances exuded by some plant roots but not others. Surprisingly, very few plants have been tested, including the prairie forbs native to Chicago. Additional plant remediators would allow the re-imagining of the post-carbon landscape and the revaluing of these degraded properties.

The program is constructed as a series of interim approaches that model time in relation to investments, benefits, and complexity. We also evolved an in situ soil prep method for keeping all soils on site, repurposing a road-building tool. A typical corner site hosts the field trials for the program and was designed for legibility and function. Students from four communities of practice — art, soil science, horticulture, and STEM learners—have been involved in the project, paralleling Hawkes’s Four Pillars. Because the Commissioner was very adventurous, the explicit aims of the project largely matched my professional intentions: to extend the plant palette and create more value(s) through remediation and to simultaneously conduct “Civic Experiments” as public research, involving many learners and creating capacity. The purely disciplinary ambition to critically extend the sculptural genre of the “earthwork” remained tacit.

Four communities of practice involved in SLOW Cleanup, clockwise from top left: art and design students doing sitework, a soil science university research lab, horticulture training for ex-offenders, and STEM learner workforce development. Images by the author.

Working with soil scientist Dr. A. P. Schwab,15 we have identified twelve new species of native ornamental petroleum remediators. Schwab has worked contractually like an artist, which is to say, for free. Conversations over time with Schwab have made clear that the intellectual merits and significance of the work were compelling enough that Schwab was willing to work outside the conventional research paradigm of hard science and to enter the non-compensation, symbolic economy of art, where participants often work completely “in kind.”

Diaspore /dī′ə‑spôr′/

In botany, a seed or spore, plus any additional elements that assist dispersal.

The pan-Atlantic exchange of plants and people that began in 1533 with the European encounter with the Peruvian potato is extended through reciprocity to all sites where food production and cultural production are intertwined. We were introduced to the City of Lima, Peru, through CIP, the Centro Internacional de la Papa,16 which holds over 4,000 varieties of Andean potatoes, the cultural heritage of ten thousand years of hybridization by indigenous growers. I had been in conversation with the Director concerning the cultural nature of food ways and the Four Pillar model, and how these ideas might enrich the new urban agriculture program underway in Lima, with which she was involved. We assembled a team of Chicago artists, designers, and preservationists to provide creative support to the City of Lima in their efforts to integrate architectural conservation for the historic center and food planning.

A crumbling but magnificent UNESCO World Heritage Site built around 1500, the historic center of Lima now houses the urban poor, who also have inadequate nutrition and food security. Similar to other quickly urbanized areas in South America, the city edge is extended by informal settlements of a growing population. Lima has a host of challenges beyond population. Due to the prevalence of the Spanish-style courtyard house, most of the open space is interior and private, not public. The diminishing glacier-fed water supply, visible in the dry beds of local rivers, also creates a challenge for this desert city. Slowly we became aware that all programs in Lima must be evaluated against the underlying pragmatic dilemma of sustaining a city that is in the wrong place — a perpetual colonial legacy — an unsustainable settlement pattern. Lastly, many of the adobe brick Spanish colonial buildings are mere shells with no extant interior. These are remarkably common. These contradictory conditions informed our strategies in Lima as we sought symbolic and practical solutions to enhance democratic participation, food security, and heritage conservation.

Diaspore /dī′ə-spôr′/. Image by the author.

During our work in Lima, a hex pattern emerged as a motif for many of these investigations, moving from a metaphor for participation at City Hall, the Civic Hive, to a space saving spatial configuration for roof gardens, to a motif for a mobile orchard, reversing the private courtyard and the spatial interiority17 of the city. While design tropes such as the hex shape allowed us to navigate between the symbolic and the practical, everyone understood that urban agriculture in Lima was a short term proposition, raising as many questions as it answered.

The 606

Returning to Chicago, from 2012 to 2016 I was the Lead Artist on the Design Team for a 3‑mile long rail adaptation project, The 606, which opened to the public in June 2015. The 606 is a civic experiment in every way, a public/private partnership with great ambitions. For me, the project has also been an opportunity to actualize the ideas that we had been developing at a more speculative scale.

The private partner, The Trust for Public Land, established public engagement as the ethos of the project. Working rhetorically with the values of participation and engagement, the arts became the organizational framework for the project, shifting the multidisciplinary team structure towards the more collaborative (but more contested) trans-disciplinary model. Sustainable “best practices” were used throughout the project, but there was no time for a philosophic discussion concerning cultural aims. Tacitly we transformed the Four Pillars into a set of cultural values — Expression, Participation, Innovation, and Sustainability—shifting the focus from cultural heritage to cultural futures.

There are many features along the 3‑mile project, including an observatory at the west end and a multi-functional skate park/performance venue at the east end. However, my main interest is a planted line that runs the full length, forming what came to be called an embedded artwork, a landscape intervention, achievable only by proclaiming it “art.” Environmental Sentinel is a climate monitoring artwork, a planted line of 453 native, flowering trees, Amelanchier x grandiflora (Apple Serviceberry). The five-day bloom spread of this flowering line will visualize Chicago’s famous Lake Effect in spring and fall. The proposal was based on a climatological study, which reveals how large bodies of water like Lake Michigan affect local temperature patterns.

Phenologic Concept for Environmental Sentinel for The 606. Image drawn by the author, courtesy of The Trust for Public Land. Embedded plant images courtesy of oregonstate.edu; JaneMT; dufour24; island native; Robert Videki, DoronicumKft, bugwood.org; and The Dow Gardens Archive, Dow Gardens, bugwood.org.

Modeled after the Japanese cherry blossom festival whose transient blooming has attracted audiences for centuries, this phenologic spectacle will become living data visualization in time and space. Phenology — from the Greek “to come into view”—is the practice of observing natural events like bloom time, and it is undergoing a revival because living indicators provide integrated data and can tell us more about climate than isolated instrumentation. Japanese court records of exact bloom-date extend back 1200 years, producing the oldest and most important phenologic data set worldwide. Unlike contemporary approaches, this data set was generated culturally, by the appreciation of beauty; it was not generated by science, nor by social responsibility. As a form of speculative artistic activism, Environmental Sentinel explores the potential of the cherry blossom festival to be replicated elsewhere. Is it a “transferable model”? Will this work in Chicago with native plants? Can beauty be catalytic and educational?

A participatory observation program links academic and citizen scientists, deliberately “sensing the anthropocene,”18 but most encounters will be informal, by regular trail users who engage this Slow Spectacle in other ways. This synthetic approach blends new participatory art practices, climatology, and the expressive potential of public infrastructure to create what we are calling, a bit provocatively, “pink infrastructure.”19

Tactics For Praxis

Collectively, these projects extend and explore the cultural dimension of sustainability and model new cultural strategies for creating change. The projects interrogate and reflect on contested models of sustainability and develop the radical strategy of “opting IN.” Several tactics for new cultural praxis have emerged from this work, including:

• Transliteration — the moving of parts across sectoral borders

• Re-valuation — the identification of underutilized assets

• Performativity — the adoption of the means of other professions for translation, redirection, disruption, diplomacy, solidarity — value-added

• and the use of multivalent intentions to deploy the ambiguity of the cultural voice to open space for new questions.

Here, the important dynamics are not binary between, say, autonomy and agency, but rather transactional, free agency, and multivalent double agency. Each of these tactics contains some degree of transgression. Even when diplomatic, change agents don’t always play by the rules. And lastly, there is much to learn about the relation of the symbolic to the practical—the useful, the purposeful, the utilitarian, and the instrumentalized — as art and culture re-negotiate their relationship to other forms of knowledge towards sustainability.

Review

By Jonathan D. Solomon

What can architecture learn?

Frances Whitehead doesn’t ask this question explicitly, but in Civic Experiments: Tactics for Practice, she presents implicit answers that are worth explicating.

Whitehead, a sculptor whose recent work is in the territory of landscape architecture, works as an outsider agent in the “tropological trans-diciplinary”: she seeks in her work to graze expertise across disciplinary territories. Soil ecology, for example, is an expertise, or a knowledge, that Whitehead takes for a nourishing walk, across the fields of art, design, and politics in her project SLOW Cleanup. This kind of work makes an instrument out of knowing how to know, specifically how to herd knowledge and move it around — what Whitehead invokes Sacha Kagan to call “double change agency.” It is also an actualization of Whitehead’s own 2006 “What do Artists Know?,” a litany for art knowledge that includes “synthesizing diverse facts, goals and references — making connections and speaking many ‘languages’” and “making the explicit implicit, making the visible invisible.”

What do artists know? How to question their own knowing.

If Whitehead points, implicitly and explicitly, to architecture and design as the territories of strategic thinking to which artists must respond with a “knowledge claim” for the civic sector, how does her decade of work on “tactics for praxis” create a territory with a knowledge claim of its own for these fields?

If we take architecture for a nourishing walk through Whitehead’s “tactics for praxis,” what can architecture learn?

Architecture can solve problems in one territory and problematize in another. Whitehead’s SLOW Cleanup improves the quality of the environment by removing toxic chemicals from the soil, and it creates value in the city by allowing previously vacant urban parcels to move onto the market. At the same time, the project problematizes value with the “symbolic economy of art,” as students learn outside the classroom and scientists make discoveries outside conventional economies of research.

Architecture both acts and implies: it has both measurable outcomes and embodied meanings. Whitehead presents her work on the 606 in Chicago as a simultaneous enactment of best practices in sustainability and of the broad aims she terms “cultural futures.” Her contributions in landscape architecture pull across data visualization, phenology, and citizen science. “Can beauty be catalytic and educational?” is a question architects can also ask.

For architecture to have a culture, it needs to have a -culture. Whitehead’s DIASPORE explores colonial legacy, ecology and urbanism in Lima, Peru through the entanglement of food production and cultural production. It is a remarkably durable mesh of culture and agriculture. Architecture’s “culture” — it’s discourse — cannot exist outside of its “-culture” — its nourishing medium.

Notes

1

Fry attributes this model to himself, in combination with Ezio Manzini and Félix Guattari, as confirmed in email, April 11, 2010.

2

Frances Whitehead, 2006. Available in original from at http://www.embeddedartistproject.com/whatdoartistsknow.html, April 1, 2015.

3

Clive Dilnot, Solidarity Through Artefacture? From “The Fear of Acknowledging Making,” drafted c.1989, unpublished.

4

MAP with Janeil Engelstad, derived in conversation with Frances Whitehead.

5

Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Dijon, France: Les Presses du réel, 1998).

6

Claire Bishop, “The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents,” Artforum 44: 6 (February 2006): 179 – 185.

7

Ben Davis, book review of Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible (London, England, and New York, NY: Continuum, 2006; 1st published 2004), http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/books/davis/davis8-17 – 06.asp. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

8

John Dewey, Art as Experience (1934), reprinted as John Dewey: The Later Works, 1925 – 1953, vol. 10, ed. Jo Ann Boydston (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1987).

9

Mrill Ingram, “The Diplomacy of Art: what ecological artists offer environmental politics,” Annual International Conference of the Royal Geographical Society, London, England, August 31 to September 2, 2012.

10

Ted Purves, ed., What We Want Is Free: Generosity and Exchange In Recent Art [SUNY Series in Postmodern Culture] (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2004).

11

Tony Fry, Redirective Practice, An Elaboration, http://www.desphilosophy.com, Volume 1 (2007) [site no longer available]; see also Tony Fry, “Redirective Practice: An Elaboration,” Design Philosophy Papers 5: 1 (2007): 5 – 20.

12

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendall (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1984), 81 – 82.

13

Sacha Kagan. “Art effectuating social change: Double Entrepreneurship in Conventions,” 4, in http://www.leuphana.de/fileadmin/user_upload/PERSONALPAGES/Fakultaet_1/Kagan_Sacha/files/version_2.0_article_ent3.pdf. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

14

Jon Hawkes, The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability: Culture’s essential role in public planning (Melbourne, Australia: Common Ground Publishing, in association with the Cultural Development Network (Victoria), 2001).

15

http://soilcrop.tamu.edu/staff/schwab-paul/

16

https://cipotato.org/

17

Jörg Plöger, “Lima — City of Cages” European Journal of Geography, article 377 (June 5, 2005).

18

Deborah Dixon, Professor of Geography, School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow, Scotland, email correspondence, November 6, 2014.

19

References and redirects the well-known ecological urbanism concept of turning “grey infrastructure” into “green infrastructure.”

Biographies

Frances Whitehead is a civic practice artist bringing the methods, mindsets, and strategies of contemporary art practice to the process of shaping the future city. Connecting emerging art practices, the discourses around culturally informed sustainability, and new concepts of heritage and remediation, she develops strategies to deploy the knowledge of artists as change agents, asking, “What do Artists Know?” Questions of participation, sustainability, and culture change animate her work as she considers the surrounding community, the landscape, and the interdependency of multiple ecologies in the post-industrial city. Whitehead’s cutting-edge work integrates art and sustainability, as she traverses disciplines to engage with engineers, scientists, landscape architects, urban designers, and city officials in order to hybridize art, design, science, and civic engagement, for the public good. Whitehead has worked professionally as an artist since the mid 1980s and has worked collaboratively as ARTetal Studio since 2001. She is Professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Email: fwhite@artic.edu

Jonathan D Solomon is co-editor of Forty-Five and Associate Professor and Director of Architecture, Interior Architecture, and Designed Objects at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His drawings, analytical and counterfactual urban narratives appear in Cities Without Ground (ORO, 2012) and 13 Projects for the Sheridan Expressway (PAPress, 2004). Solomon was curator of the US Pavilion at the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale and of “Outside Design” (2015) at the Sullivan Galleries in Chicago. His interests include extra-disciplinary, post-growth, and non-anthroponormative design futures. Solomon received a B.A. from Columbia University and an M.Arch. from Princeton University and is a licensed architect in the State of Illinois. Email: jdsolomon@forty-five.com