When these two numbers are put together, people usually sit up and pay attention. John Wayne stands tall with his “Colt 45,” and Clint Eastwood faces off with his “S&W 44 Magnum.“1 There’s only a hundredth of an inch separating the two calibers, and a generation of contention as to which is the finer round or revolver. The number 45 can be flipped to make 54, and pleasure seeking Baby Boomers come to mind, singing along with the Village People’s iconic tune YMCA against the backdrop of Studio 54, New York’s iconic 70s disco. So what happens in the brain when it hears something so reduced in size and economical in its symbolism as two numbers, juxtaposed either forwards or backwards?

For all of the Steampunk cogwheels and curly-cues of the Victorian age, cartridges and bullets are amongst the most abstract shapes to come out of the Industrial Revolution, a perfect union of straight line and curve.2 From the outside, a cartridge is haunting in its reduced simplicity: little more than a truncated cylinder of gleaming brass filled with gunpowder, into which is wedged a lead bullet. The nose cone of a bullet is a round ogive shape, designed to slice through wind with optimum efficiency. Yet, for all its modernist austerity, a bullet is pregnant with the capacity for a life changing, visceral, nasty, messy, causality. Who would have known that such ghastly termination could be born from such pure form? The clue is the ear-splitting crack-bang that accompanies each shot. The raw power of that noise, whose only parallel in nature is a thunderclap, feels like all the noises of the world have been compressed into a split second. Surely that alone tells us something. And not to be forgotten is that, when the chips are down, the cartridge becomes currency, not worthless paper money. The real price of life is unambiguously mirrored in the simple form; one is exchanged for the other.3

What we know today as a “bullet shape” started out as a perfectly round sphere of lead used for centuries in matchlock, wheel lock, and flintlock muskets and pistols up until the 1830s. Keplarian globes would sail through the air in constellations from massed volleys of smoothbore muskets, from the ranks of British Red Coats and American Revolutionaries alike. The leaden balls would yaw and arc through space, inaccurate and going their own way, hoping for a chance hit upon their unfortunate adversary. The balls were big, slow, and heavy, between one-half and three-quarters of an inch in diameter. A musketeer, if his view was unsullied by smoke, could watch the unhurried passage of the ball form a shallow parabolic arc as it wended its way into the heart of darkness. Basic military ammunition is still called Ball ammo, despite no longer being spherical.

.75 caliber and .70 caliber ball ammunition from the Revolutionary War. Collection of the author. This generation of bullets weighed around an ounce. They were easily dropped down the muzzle of smooth-bore muskets, as their diameter was smaller than that of the barrel. They were by no means perfect spheres and the casting sprue would be snipped off by the soldier, causing a further diminishment in accuracy.

.75 caliber and .70 caliber ball ammunition from the Revolutionary War. Collection of the author. This generation of bullets weighed around an ounce. They were easily dropped down the muzzle of smooth-bore muskets, as their diameter was smaller than that of the barrel. They were by no means perfect spheres and the casting sprue would be snipped off by the soldier, causing a further diminishment in accuracy.

Inventing the .44 Caliber Ball

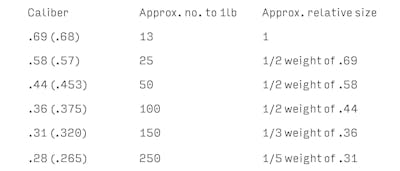

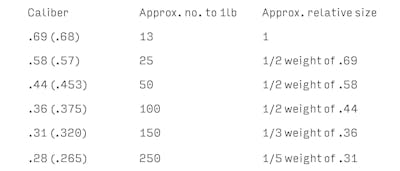

It may be wondered why some of the standard ammunition we know today, such as .44, .36 and .32 calibers, have such seemingly irregular dimensions. The reason is deceptively simple. The standard .75 Caliber Brown Bess of the 1776 Revolutionary War musket used a .69 caliber ball and weighed approximately 1¼ ounce or thirteen to a pound. The table below shows the relative weights of smaller ammunition.4

The diameter of ball ammunition began to diminish when barrels could be inexpensively rifled, as an accurate shot is more deadly although the ball is smaller. When Samuel Colt patented his revolver mechanism in 1836, a new search for the right caliber ball ammo was set in motion. The Colt Paterson .36 caliber revolver, considered by many to be one of the most elegant handguns ever made, could fire five shots in quick succession. For the nascent gun industry, the search was on for a revolving handgun that was the right mix of firepower, caliber, lightness, and ease of manufacture to reliably deliver more shots on target if the first one missed.5

Colt Paterson No. 5 Revolver M1836, .36 caliber. Photo courtesy Woolaroc Museum, Bartlesville, Oklahoma. One of America’s finest collections of Colt Paterson revolvers, as well as many other Colt pistols, is at the Woolaroc Museum off the beaten path in rural Oklahoma. The Colt Firearms Museum, within the Connecticut State Library, could make the same claim. To give a sense of their epicurean rarity, in 2011 a Colt Paterson sold for $977,500. When visiting Los Angeles, another great collection of Colt Patersons is at the Gene Autry Museum, home of the “Singing Cowboy,” in Los Angeles. This Los Angeles museum has a premier collection of revolvers embellished by the very best 19th-century German- American engravers. For anyone interested in art & technology, the Greg Martin Gallery in the Autry Museum is a must-see place.

Colt Paterson No. 5 Revolver M1836, .36 caliber. Photo courtesy Woolaroc Museum, Bartlesville, Oklahoma. One of America’s finest collections of Colt Paterson revolvers, as well as many other Colt pistols, is at the Woolaroc Museum off the beaten path in rural Oklahoma. The Colt Firearms Museum, within the Connecticut State Library, could make the same claim. To give a sense of their epicurean rarity, in 2011 a Colt Paterson sold for $977,500. When visiting Los Angeles, another great collection of Colt Patersons is at the Gene Autry Museum, home of the “Singing Cowboy,” in Los Angeles. This Los Angeles museum has a premier collection of revolvers embellished by the very best 19th-century German- American engravers. For anyone interested in art & technology, the Greg Martin Gallery in the Autry Museum is a must-see place.

Large .70 caliber to .50 caliber round musket balls were too powerful for the new revolvers, and Paterson’s .36 caliber ball was a tad too light, so the military determined that a spherical bullet of .44 inch diameter would be the optimum size for reliable stopping-power from a handgun. The .36 caliber bullet would still do the job at close quarters, but the .44 spelled out unambiguous power.3

Remington 1858 Sheriff Model, .44 caliber cap and ball. Collection of the author.

This almost new (98%) reproduction was made by Pietta and was bought at a gun show for $75. Firearm research starts at gun shows where, unlike museums, everything can be handled without kid gloves and there is a wealth of shared knowledge at hand. Gun shows are largely “cash & carry” affairs in which attendees and amateur sellers carry wads of $100 bills, peppered by $20s. Professional dealers require a background check to complete the transaction for any gun made after 1898. Not so the amateur dealer. For firearm collector/scholars, a gun show is about as much fun as can be had for a $10 entry fee and, although I hate to say it, it is as equally interesting as an art museum.

For the Civil War foot soldier, the delicate balance between the stopping-power, the weight of weapon, and the quantity of bullets that could be carried was critical. Civil War buffs armed with metal detectors still find caches of lead bullets dumped in the field, as they were too heavy to lug around day after day. A perfect balance between the manufacturer and the soldiers’ needs was achieved with the sleek Colt Army Model 1860, a .44 cal. cap & ball revolver. It was a masterpiece of ergonomics and mechanical efficiency, with the power to stop six people in their tracks. It is a thing of beauty, albeit dark.

Colt Army 1860 revolver, .44 cal. Photo courtesy the Colt Firearms Museum, Museum of Connecticut History.

The barrel and fore-frame are made from one piece of steel and sculpted for maximum economy of weight. Its androgynous form was manufactured either by casting, milling machines or by being forged: the curved cuts are considered to be a marvel of technology wedded to art.

The spherical lead ball was reengineered for the rifled Springfield muskets of the Civil War of 1860 – 1865 with an elongated bullet of ogive form. This was further refined with the Minié Ball. It had a deep recess at the rear and tapered to a thin skirt of lead at the base, known as a Cylindro-conic Ball.6 As the black powder blew, the lead skirt expanded into the grooves of the rifling and made a tighter and much more efficient use of the propellant. This simple redesign meant that the bullet could travel faster with the same amount of powder and yield greater stopping-power. As the efficiency of the bullet’s design increased, over time the nominal .58 or .69 calibers of the Civil War firearms began to decrease, getting closer and closer to the magical numbers of .45 & .44.

Civil War hollow-base “Minié” and solid bullets. Collection of the author. Civil war bullets are miracles of design, having some of the most minimalist profiles of the 19th century. The bullet on the bottom row on the right is a rare .41 cal. round for the Volcanic Pistol, based on the design concept of Hunt’s "Rocket Ball." The powder charge is in the hollow of the lead bullet, as is the percussion cap, dispensing with the need for a copper cartridge shell. The Volcanic pistol was so underpowered that it was ineffective at anything but close range, but the design gave birth to the Henry 1860 "Yellow Boy" and 1873 Winchester lever action rifles. This Volcanic round was found on a Civil War battlefield in a cache of twelve unused examples, implying that they were dumped, dropped, or fell with a soldier. Good archaeological practice could have answered that question, something that a metal detector is not programmed to do.

Nowhere but in warfare, where life and death are in the balance, is design so critical to gain the upper edge on the competition. This intensity of professional engagement is something that does not occur with the design of the latest espresso machine. Unable to determine whether firearms neatly fall into the category of weapons, art or science, schools and museums of design frown upon firearm studies as a wayward child, despite holding themselves up as the gatekeepers of design theory.7

The .22 & .44 Metallic Cartridge

The problem with lead balls and loose black powder wrapped in cartridge paper was that they were slow to load and susceptible to misfire during rain, a situation made marginally better by the invention of the percussion cap ignition system. The second problem with paper cartridges was that breech-loading guns could have a gap between block, breech, and barrel through which the explosive gasses escaped.

12mm Lefaucheux Pinfire cartridge and 6mm Flobert. Collection of author. The pinfire cartridge was perfected by Eugène Lefaucheux, on his father Casimir Lefaucheux’s 1837 patent. The Flobert 6mm (.22 BB Cap) is the first metallic waterproof cartridge with primer, propellant and bullet contained in a copper shell. Later versions added gunpowder to increase the muzzle velocity, although Flobert had inserted that eventuality in his 1849 patent.

To address these shortcomings, Frenchman Casimir Lefaucheux designed the first viable metallic cartridge in 1837 and, by 1854, his son Eugène Lefaucheux had refined the Lefaucheux M1854 revolver to fire six 12mm (.47”) caliber pinfire cartridges. Not only were the cartridges largely waterproof, but also the metal case effectively sealed the gap between the breechblock and cylinder in a process called obturation, meaning to close or obstruct.

Lefaucheux Brevete, Model 1854 pattern, third type, known as the "Stonewall Jackson," 12mm Pinfire Revolver. Collection of author.

In 1845, Louis Nicholas Auguste Flobert invented a truly waterproof metallic cartridge, composed of a 6mm (.22”) lead ball mounted onto a percussion cap primer. By the late 1850s, Flobert had developed his “parlor pistols” to fire the tiny cartridge in several calibers, including 4mm.8

Flobert Parlor Pistols, 6mm (.22cal). Top: Houllier Blanchard Parlor Pistol c. 1845-1865. Bottom: German "Zimmerschutzen" reproduction of 19th-century Flobert pistol, circa 1950. Collection of the author.

Gilles Mariette made the barrel for this Houllier Blanchard pistol; Mariette was a Belgian gunsmith of great inventiveness, having patented the double action pepperbox revolver in 1837. Houllier was of equal stature, and held patents on cartridges. “Flobert” parlor pistols are transitional firearms, the first guns to use fully contained wedge-shaped waterproof cartridges; they were not rimmed, as are the modern versions shown here. Early Flobert pistols made the large hammer double as a breechblock. Later versions used a complicated three-piece mechanism known as the "Remington System," with separate parts for extraction, a breechblock, and a hammer. There is scant literature on Flobert pistols, and you find them in unusual places and often mis-cataloged. Parlor Pistols were originally used for indoor target practice; they are still used in Europe, as stringent firearm laws do not regulate the cartridge. In his book The Banquet Years, Roger Shattuck described Parisian intellectuals entertaining themselves with guns in cafés; one particularly good marksman could shoot the pipe from an unsuspecting tippler. It was probably done with a Flobert.

Smith & Wesson recognized the full potential of the French developments in waterproof metallic cartridges, patented in France, but not in America.9 Smith & Wesson took an exclusive license out on Rollin White’s Patent 12,649 of April 3, 1855, which bored a hole through the cylinder of a revolver to enable it to accept the new metallic French cartridge. With the help from Tyler Henry, they then designed and patented a new copper rimfire cartridge whose rim sat securely in the back of the cylinder, making it easy to extract. The S&W patent for the cartridge also placed a reinforcing disc at the base of the cartridge. This prevented it from swelling with the explosion, which had jammed the revolving cylinder in the earlier cartridge designs.10 The breakthrough revolver and cartridge design resulted in the Smith & Wesson Number 1 revolver that used a .22 caliber cartridge of the same name. This is an example of how a gun (the hardware) and its ammunition (the software) are designed together to make a perfect integrated design. At first, the caliber of rimfire ammunition was kept small, as it was easier to manage the design problems but, as time went by, the rimfire metallic cartridge increased in size and doubled its diameter of .22 to reach the optimal stopping-power of the .44 caliber bullet.

Whitneyville Armory Model 1, 2nd Series, 1872-3, .22 Short. Collection of the author.

Based on the S&W Number 1, the Whitneyville was made by the Whitney family, who developed the machine tools that set in motion the “American System” of making identical and interchangeable components. Smith & Wesson perfected Flobert’s all-in-one cartridge design with the “The Smith & Wesson No 1 cartridge,” known today as the .22 Short, for which S&W added a rim to aid its seating in the cylinder as well as extraction. Although diminutive, it is a lethal round. When shot in the 1860s, the wounded were likely to die of infection. The .22 Short, loaded with black powder, was the first American rim fire cartridge invented and has been in continuous production since 1857. Few, if any, designed objects of the Industrial Age have lasted unchanged for one hundred and fifty-eight years. Remarkably, later versions of the S&W Model 1 revolver can still be bought for under $300. This one was chosen by the author because of its association with a branch of the Whitney family, of Whitney Museum of American Art fame. Art and technology, as well as war and peace, are never far apart. Note the modern .22 Shorts in the photograph use smokeless powder and are loaded too "hot" for this gun; they could blow out the cylinder!

Rimfire ammunition reached its zenith with a full-size rimfire .44 caliber cartridge, initially designed for the Model 1860 Henry lever-action repeating rifle. The rifle could be loaded with fifteen cartridges, plus one in the chamber, a devastating amount of firepower for the time. The 1860 Henry is now considered to be the first “assault rifle” used by a military. The Yankees of the War of Northern Aggression (aka the American Civil War) used the rifle to cause havoc in the ranks of the Confederate Rebel Army who complained, “That damn Yankee rifle that they load on Sunday and shoot all week!” A Union diarist replied, sending a note back to Johnny Reb of a “…leaden compliment.”

Henry 1860 Repeating rifle, sn# 3469. Photo courtesy of the Frazier History Museum.

This rifle was presented to David Reed, sometime after 1863, after being wounded fought at Gettyburg. The Henry 1860 Repeating Rifle and .44 Henry rimfire cartridges were designed together as one synonymous system. The Union Army bought over 4.6 million rounds of Henry ammunition.

.44 cal. and .44 Henry Rimfire cartridges. Collection of the author.

Collecting ammunition is compelling if only because the forms are aesthetically beautiful, a perfect wedding between straight-line and curve, as you would expect for an object that flies through the air at great speed. To have in your hand something so small, yet so terminally momentous, is sobering. One wonders how an object, as perfect in shape as an egg, could wreak such explosive havoc. Today, the universal availability of ammunition outside of America’s cities is ubiquitous: it lies in stores in stacks on open shelves, as if it were no more consequential than cans of beans.

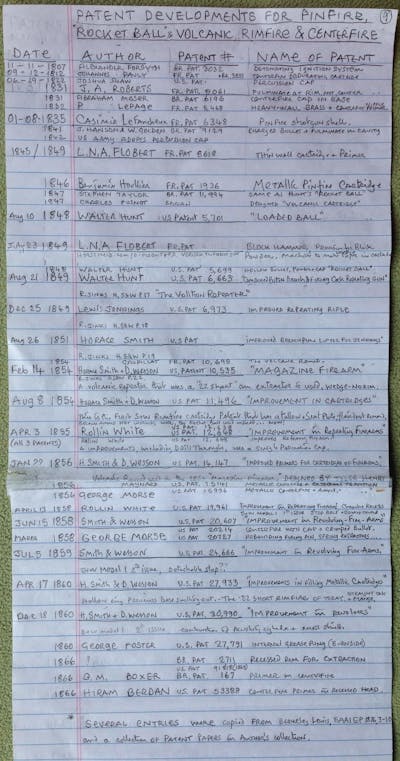

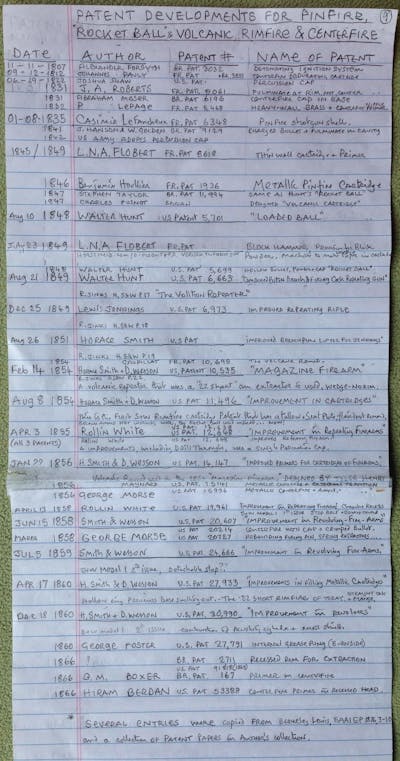

Patent developments leading to the 1855 Smith & Wesson .22 Rimfire Cartridge. Notes of the author.

The development of the rimfire cartridge is as complicated as it is fascinating, and shows an evolution of design that is as thrilling and high-stakes as any. In addition to inspecting prototype and production cartridges in person, it requires following French and American patent development for both ammunition and firearm designs that weave in and out between revolver and repeating arms inventions.11 In the US, Smith & Wesson were developing two kinds of ammunition: the case-less .31 or .41 "Volcanic" and the metallic case .22 "Short." Initially, the Smith & Wesson Magazine Pistol (the Volcanic) was designed for metallic case ammunition, but for production in 1853 the case-less Volcanic round was chosen, probably because the technique of manufacturing the metal case had not been perfected. The Volcanic was an underpowered design that was not effective, and the business failed. A new company was formed, and the S&W Model I revolver was brought out in 1857, by which time a successful .22 rimfire cartridge could be manufactured. In 1860, the mechanism of the Volcanic repeater and a .44 rimfire cartridge, perfected by B. Tyler Henry, were wedded to make the 1860 Henry Rifle. B.T. Henry designed and built the first effective machinery of the mass production of metallic cartridges.12 But Smith & Wesson were not the beneficiaries of the ground-breaking lever-action rifle; that would be the prize of Oliver Winchester, its new financial backer.13

The Design Dance: Optimal Everything

By the time the rimfire cartridge had been perfected, and before the centerfire cartridge had come into being, all of the essential elements of the modern day cartridge had been identified: the optimal bullet size, the right quantity of powder, and a reliable percussion system brought together in one waterproof metallic package. Developers of cartridges negotiate between many parameters to achieve greatest efficiency, and juggling these factors is nothing short of a design dance. Today, the outcome of these design decisions is quantified by standardized expressions of performance. The weight of the bullet is expressed in grains, as is the powder that propels the bullet. The outcome of the right combination of these two variables is expressed as the “muzzle velocity,” the speed of the bullet measured in feet per second when it leaves the barrel of the gun. The power of a bullet is called the “muzzle energy,” expressed in ft.lbs or Joules. A very heavy bullet moving slowly can have similar destructive energy as a light bullet moving fast; naturally, the energy decreases with distance as the bullet slows, which is why the aerodynamics of the bullet counts.

But these are not the only factors in the performance of a cartridge. Black powder left considerable residue in the barrel that literally jammed up the works and made the gun inoperable after a number of shots. This led to another design advance, the addition of incised rings in the lead bullet into which grease was inserted to lubricate the bullet as well as help clean the barrel of residue. The design of gunpowder is also critical, and chemists working in each country had a huge impact on the design dance of the cartridge. Add to the mix the right length of the barrel, for if all the powder has not been burned by the time the bullet leaves the muzzle of the gun, powder and energy is wasted. And if the barrel is too long it becomes unwieldy and if too short it becomes inaccurate. Chemists worked hard to create more explosive fast burning “smokeless” powders to accelerate the bullet in shorter barrels, but the consequence was that the lead of the faster moving bullet was deposited in the barrel. This unforeseen problem resulted in a new design-development to coat the bullet in copper, leading to the Full Metal Jacket (FMJ) bullet. The design dance constantly shifts with each advance of technology.

The design of a cartridge is every bit as time-consuming and complex as the design of the gun that fires it, and why some of the most successful cartridges and firearms were designed together as one system. The optimal balance between the two can be equated to the design of hardware and software in computer design, and has equal consequence.

Centerfire .44 & .45 Ammunition

Ammunition went through its next big evolution with the invention of the centerfire cartridge. It used a modified percussion cap called a primer, set into the base of a brass shell to ignite the black powder. This development quickly made rimfire ammunition obsolete, except for the .22 caliber round. In 1866 and 1869, patents were issued for the Berdan No. 1 primer and the Boxer primer, proprietary variations of a small disposable copper cup filled with mercury fulminate that ignites when struck with a hammer. The new primers were wedged into the base of a metallic cartridge and designed to be easily replaced, meaning that the brass shell could be reused several times. This was a vitally important design-development. Living on the Western Frontier required that you recycle your own ammunition from a collection of brass shells, replaceable primers, a can of black powder, and a bag of lead bullets. It was an early example of recycling mechanical parts in the Industrial Age. A trip to Wal-Mart to stock up on ammo was a distant concept at that time.

In Great Britain, .450 caliber black powder centerfire cartridges were introduced in 1868 for the Adams revolver. The more powerful .455 cartridge was developed for the 1887 Webley Mk. 1 revolver. In America, the large-frame Smith & Wesson Number 3 revolver of 1869, generically known today as the “Schofield,” used the new .44 caliber American centerfire cartridge.14 The revolver’s top-break design, coupled with the new star-ejector, meant that you could eject all spent shells simultaneously, resulting in very fast reload times. It was a revolutionary design. Four years later, Colt introduced the legendary Model 1873 Single Action Army revolver, the Colt 45, designed specifically to shoot their proprietary .45 Colt cartridges. These were 40% more powerful than the .44 S&W American cartridge. The Colt .45 used 35 grains of black powder rather than 23 grains for the Smith & Wesson .44. It should be added here that the .44 S&W American, Russian, Special, and Magnum cartridges all use bullets of a nominal diameter of .429”. Smith & Wesson were alert to good advertising and probably used the moniker “44” to take full advantage of the catchy name of the number, that is so closely associated with their brand.15

Smith & Wesson Number 3, First Model, .44 cal. S&W. Photo by the author, used with permission of the J.M. Davis Arms & Historical Museum, Claremore, OK.

A brilliant design that introduced the top break and star-ejector, but it lost out to the Colt SAA .45 cal. in the US. Perhaps it was based on looks because, let’s face it, this one is a bit dumpy. Its lack of success was more likely due to intransigence on the part of S&W, to not accommodate their competitor Colt’s more powerful .45 cartridges by adding a lengthened cylinder & frame, although they did do that for the .44-40 cartridge. Corporate pissing matches equate to the fight at O.K. Corral or a couple of professors staking their careers in the classroom. In animalistic displays of predator & prey, each can end with winners and losers. This particular S&W is from the Davis Museum in Oklahoma, a treasure trove of 13,000 guns, kept in a Bruto-Modernist concrete box. They are arranged in custom built black-painted steel cases fitted with pegboard and lit by neon. The architects Prouvé, Breuer, and Mies would have been proud of their influences, in equal measure.

Colt SAA 1873 .45 cal., 5½” barrel, Uberti Cody Cattleman reproduction. Collection of the author.

From the emotive point of view, this revolver, known as a “Hog’s Leg,” has been lying on my worktable for the past four days, migrating from one spot to another. It is photographed on top of a MacBook Pro belonging to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, a perfect backdrop. I ask myself over and over again, “Why is the design so compelling?” Certainly it is the gun of boyhood dreams, of lying on the floor in front of the neighbor’s telly watching the Lone Ranger in the 1960s, but surely that is not enough to irrigate my aesthetic imagination alone. Do we dare admit, in this age of equal opportunity, that there is such a thing as beauty and “Getting it right,” where all parts are in perfect harmony? The long tube attached to the side of the barrel is both counterintuitive and ugly, yet the revolver would not get a gazillion “likes” without it.

From a technical point of view, the Colt Single Action Army was made with the same machinery used for the Model 1860 percussion revolver and some of the parts interchange. (The Colt factory burned in 1862, and the machinery was all in good condition, having been made in 1863.) The designer William Mason changed the cylinder and frame, adding a top strap (U.S.Pat. 51,117, Nov 21 1865), a housing for the ejector rod, and a loading gate (U.S Pat. 158,957 Jan 19 1875). The barrels were rifled with the same machinery. In both cases, the groove diameters are .451”. So the .45 really is a .45.16

The Colt SAA was chambered for its proprietary .45 Colt cartridges. The US Army preferred the heavier Colt load to the S&W .44 and replaced the S&W Number 3 revolver with the Colt SAA revolver in 1875. Smith & Wesson adjusted to the situation and introduced the No. 3 “Schofield” revolver, using a new .45 S&W cartridge, but it was underpowered. Another problem was that these fit the Colt .45 but not the other way around. Interchangeability of ammunition between firearms is of vital importance in the field, and the US Army recognized the problem. They promptly cancelled the fast reloading S&W Schofield and bought 24,000 Colt SAAs. Consequently, the use of S&W Model 3 Schofield .45 revolvers began to atrophy in the United States, despite being a much more advanced design than the Colt SAA, and equally well made. Even though a soldier could reload his Smith & Wesson No. 3 in half the time it took to reload the Colt SAA — a significant advantage in military and civilian gunfights — availability of ammunition over-ruled the brilliance of the gun’s design.

In a second development of the design war between the .44 & .45 cartridge, Winchester introduced its lever-action carbine in 1873 to replace the Henry 1860 rimfire carbine. The Winchester 1873 fired the new .44−40 WCF (Winchester Center Fire) cartridge, meaning that it had a .44 caliber lead bullet atop a whopping 40 grains of black powder.17 Colt immediately saw the potential of the new rifle and introduced the SAA as the Colt Frontier in 44 – 40 caliber, allowing the same cartridge to be used in the Colt revolver and Winchester lever action rifle. This made supply logistics much simpler for the frontiersman. To accommodate the increased powder, the .44−40 WCF round was necessarily 3/16th inch longer than the old .44 S&W cartridge. This meant that the longer .44−40 WCF could not fit in S&W revolvers, but S&W .44 ammo could fit into Colt and Winchester .44−40 cal. guns, an added benefit for Colt in its predator or prey battle with Smith & Wesson.

Boxer and Berdan primers, S&W .44 American, Russian and Colt, 44-40 Winchester / .44WCF and .45 Colt cartridges. Collection of the author.

What exactly is ammunition and firearm scholarship within academia, and how does it differ from the practice of a knowledgeable collector? For one thing, scholars cannot take guns or ammunition into their offices at a university or design school, at least not in the North, so that makes study impracticable. Taboo follows closely on its heels. There are tens of thousands of different kinds of cartridge, each a different design in some respect, and they need to be in your hand to examine them fully. By studying the aerodynamics, metallurgy, chemistry, techniques and location of manufacture, as well as the packaging, the faint changes between each development show the genius of invention in slow motion. Study of this pivotal aspect of the foundations of industrial design is logistically difficult and well-nigh impossible for an urban student and academic alike.

At this point, the .45 round had finally come of age in a perfect storm of design invention, marketing, interchangeability, and good fortune. Had Smith & Wesson not been so intransigent in refusing to elongate the frame and cylinder of their Model 3 Schofield by 3/16th of an inch to accept Colt’s powerful .45 cartridge, the Schofield and its .45 S&W cartridge may well have held sway in the history books. The US Army then commissioned the hybrid .45 Colt Government cartridge to fit both the .45 Schofield and the Colt .45, but it was underpowered and unsatisfactory. The damage to S&W’s relationship with the US Army had been done. However, they did plenty of business with the Imperial Russian Army, which meant that, after all was said and done, as many Smith & Wesson Number 3s were produced as Colt SAA 1873s. Whilst the competing Colt and S&W pistols had different reputations in the United States, they were equally successful qualitatively and quantitatively when both foreign and domestic markets are taken into account.

This is what happened when two manufacturers, holding a virtual split monopoly, chose not to cooperate to create a solution of interchangeable units. The result was a nightmare for the consumer cowboys of yesteryear. It shows that design does matter and can make or break a business empire. It is as if there were two AAA battery designs, each slightly different, so that they would only go into one brand or another. It’s kind of what Apple has done, but they have gotten away with it — so far.

.45−70 & .45−90 Rifle Ammo

Now that .45 Colt and .44−40 WCF cartridges were being used interchangeably between pistols and lever-action carbine rifles, a parallel development was occurring to redesign long rifles to take a more powerful black powder cartridge in an optimum caliber. It was determined that the new rifle ammunition should have between 70 to 100 grains of powder rather than 35 grains used in the .45 Colt revolver cartridge. To determine the correct caliber, in 1873 the Army set up an exhaustive “Small Arms Caliber” Board and tested a .40, .42 and .45 caliber bullet against the .50. They chose the .45.18 To address these two factors, a brass alloy shell was developed, elongated for more powder and greatly strengthened at its base. This effectively sealed the breech blocks of escaping gasses of the new trapdoor, falling block and lever-action designs. So was born the mighty .45−70 round, designed for the 1873 Springfield Trapdoor rifle, and using over double the powder of the revolver cartridge.

.45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) cartridges. Collection of the Author.

The left-hand cartridge was made in 1912, one year after its introduction in 1911. Both cartridges are FMJ (Full Metal Jacket), a requirement of the Geneva Convention that disallows lead bullets or soft tipped bullets as they are seen to cause inhumane damage. Paradoxically, the red Teflon tipped round, which expands upon impact, is legal to use in the United States by both Law Enforcement agencies and civilians alike, but not by the US Army overseas.

New design and manufacturing techniques of both rifles and cartridges had made possible an efficient, fast-loading .45 caliber rifle that could be used for hunting large game, such as deer and bison, as well as human beings, both foreign and domestic alike. But the .45 caliber rifle round was not long for this world. In the 1880s, smokeless powder was invented to produce three times the energy of black powder. This spawned a completely new generation of military rifles. The former .45 caliber bullet could now further be reduced in size to approximately .30 caliber, or 8mm in Europe. It was now left to pistol ammunition designers to determine whether the .45 caliber cartridge was the right size for a handgun. Or not.

The .45 ACP Round

By the time the 19th century was drawing to a close, a whole new kind of mechanized warfare was in the wings, and weapons were being developed to fight them. The European powers were working on their own versions of the high-power smokeless gunpowder of the 1880s, and, in the USA, DuPont and other manufacturers were developing smokeless powder. The .45 cal. black powder rifle had become a thing of the past. The new generation of rifles was designed for small, fast moving, aerodynamic bullets in the .30” or 8mm diameter range, and they delivered more kinetic energy to the target than the heavy, slower-moving .45 bullets of the black powder era.

For handguns, the powerful smokeless powder set in motion a new generation of design possibilities. There was now enough spare energy to operate the complex mechanical action of semi-automatic pistols being developed in Germany and America in the 1890s. There was also a move towards the smaller .38 and 9mm cal. cartridges. The increased speed from these new propellants equaled the kinetic energy of the large but slow moving revolver rounds and was calculated to have equal stopping power. However, Western armies found the smaller caliber fine for incapacitating people of European stock, but, when it came to suppressing their imperial subjects, particularly the Moro Warriors of the Philippines — hardy soldiers reputedly cranked up on drugs — the .36 and .38 caliber pistols were deemed to be underpowered. To solve the problem, the Springfield Arsenal reworked the Army’s obsolete Colt SAA .45s and sent them (as Artillery Models) to the Philippines with smokeless powder ammunition. The heavier round worked.

.45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) cartridges. Collection of the Author.

The left-hand cartridge was made in 1912, one year after its introduction in 1911. Both cartridges are FMJ (Full Metal Jacket), a requirement of the Geneva Convention that disallows lead bullets or soft tipped bullets as they are seen to cause inhumane damage. Paradoxically, the red Teflon tipped round, which expands upon impact, is legal to use in the United States by both Law Enforcement agencies and civilians alike, but not by the US Army overseas.

Spooked by the Moro Warrior episode, in 1907 the US Army put out a call for a new sidearm that would return to large caliber .45 caliber cartridges.19 The new round had to be rimless so that it could be used for semi-automatic pistols. In one of the most interesting competitions ever held, the major gun makers of Europe and America were pitted against each other to produce the next official side arm for the US Army. The requirement was that it should be powerful enough to fell any foe with one shot to the torso at standard distances. Ten companies entered, and the finalists included Colt, Luger, and Savage, who had all upsized their smaller .32 or 9mm caliber pistols, developed in the 1890s, to take the new .45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) cartridge designed by John Browning.20 Colt had the advantage of Browning designing both the .45 ACP round as well as the Colt .45 semi-auto pistol, and it was thought that Colt’s submission had an unfair advantage. There was the accusation, unfounded, that Colt had put less powder in the competitor’s ammunition so that their actions would not cycle properly. In a pissing contest of epic proportions, hundreds of rounds were run through each gun in a torture test, and Colt came out victorious.

The Luger, Savage, and Colt pistols were the three finalists for the 1907 U.S. Army trials for a .45 caliber gun. Collection of the author.

The Luger P-08, 9mm and Savage 1907 .32ACP illustrated here are in their original calibers before they were up-scaled for the .45 ACP cartridge. These “Trials” pistols in .45 are immensely rare as very few were made. The stainless steel Colt 1911 Government Model Series 80 .45ACP was bought by the author in 2011 and is marked “100 years of service” to commemorate the pistol’s 100th year anniversary. This particular Luger P-08 was made in 1936, at the pinnacle of its technological refinement, prior to the commencement of wartime production when standards were lowered. The Savage 1907 was a groundbreaking design, the first pistol to be held together with steel pins rather than screws and to have a double-stack magazine for ten rounds in the grips. This Savage 1907 is version 17 Model 2 and recognized to be mechanically the best of the seventeen versions produced.

The Colt 1911 heralded the third act in the saga of the .45 caliber. It signaled the birth of a new cartridge for a pistol that has become one of the two most famous handguns America has ever produced, both in .45 caliber. The Colt 1911 was accepted by the Army the same year that the Wright Brothers flew the 1911 Wright Model B Flyer but, unlike that particular airplane, the Colt 1911 has remained essentially unchanged for 100 years. It is a perfect, classic design and is still going strong. Thank you, John Moses Browning. Ten years later in 1921, the same .45ACP round was used for the Thompson submachine gun. Thank you, General John Thompson. A single round of .45ACP could be used in both a long gun and a handgun, thus simplifying the army’s ammunition supply.21 Once again, it repeated the concept of interchangeability of ammunition between handguns and long guns that the Colt SAA revolver and the Remington lever action rifle pioneered with the .44−40 cartridge.

In 1985, the U.S. Army withdrew the Colt 1911A1 from general service and replaced it with the Beretta 92B, using a 9mm round. Interestingly, after the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, soldiers displayed dissatisfaction with the lighter 9mm round, and the Army is apparently taking another look at the .45 cartridge, thus repeating a discussion between the .44 and .36 (9mm) families of ammunition. This will be the third time such a discussion has been held over the past 150 years.

The Western Movie defines the Colt .45

There is no doubt that American western movies made during the Cold War were vastly influential in promoting the mythology of the .45 cartridge. John Wayne took many of the leading roles, brandishing his Colt SAA revolver that, unbeknownst to many, was just as likely to be chambered in .44−40 as .45. The genre of the American western was established in 1939 with John Wayne in Stage Coach, a tense and sultry movie, whose heroes are the American Cavalry who save the day from Apaches, a saga that shadows the build-up to WWII and America’s preeminence against the Axis armies. The scores of American and Italian Spaghetti Westerns made from the 1950s to 1970s are thinly veiled symbols of the showdown between the Good Kennedy and the Bad Khrushchev. The Colt .45 Single Action Army revolver was emblematic of the newly mythologized global power of the emerging American Empire, where sheriffs bring outlaws to heel and heroic settlers and soldiers slaughter the backward redskins. Now that tribal casinos have come on line, the tables have begun to turn — literally. America’s indigenous peoples are now slaughtering the wallets of the settlers to this continent, both old and new. Badda-bing, badda-boom!

Special and Magnum Cartridges

The fourth incarnation of this family of cartridges is the .44 Magnum, the modern-day smokeless powder version of those OF the 1870s.22 With its redesigned brass shell, powder and bullet, the .44 Magnum is two to four times as powerful, or “hotter,” than the .44 and .45 cartridges of yesteryear. The magnum family of revolver cartridges was introduced in the 1930s, during the gangster and bootlegging era, when the police needed a round that would shoot through sheet metal car doors. Starting with the .38 Super Auto and culminating in the .357 Magnum in 1934, the caliber was increased to .44 Remington Magnum in 1955 and then the .454 Casull in 1957. The .44 Mag was primarily designed for hunting big game. It is too potent for law enforcement as the bullet is just as likely to incapacitate the perp as well as the person standing behind the perp. That is a bad situation for a policeman, but it didn’t deter Dirty Harry from using it for that purpose. The .44 Magnum cartridge has the same external dimensions as the original 1873 .45 Colt round and was designed for the massive Smith & Wesson Model 29 revolver of 1959, which was Clint Eastwood’s ‘Dirty Harry’ gun of that movie’s name.

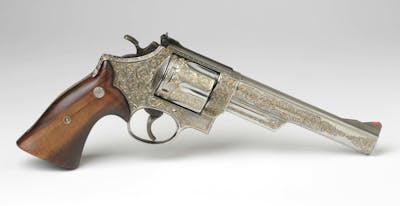

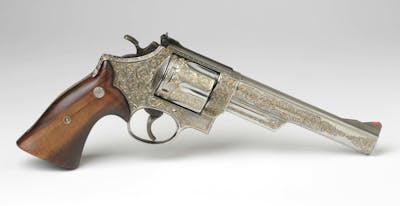

Smith & Wesson Model 29 .44 Magnum. Photograph permission of Lyman and Merrie Wood Museum of Springfield History, Springfield, MA. Photograph by John Polak (CVHM 98.00243).

This S&W Model 29 was decorated for the S&W exhibit at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, following a long tradition of making the most artistically decorated gun for exhibition purposes. It was carved and gilded by Smith & Wesson’s Master engraver Russ Smith. He mirrored the style of Gustave Young, who produced his greatest masterpiece, a Smith & Wesson New Model No. 3, for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Gone are the days when firearms are celebrated in a World Exhibition, for the intrinsic relationship between civic and military life is not so accommodating as it once was.

Internet chat rooms indeterminably engage in a longstanding banter as to whether the .45 Colt or the .44 Magnum is the more iconic round, or if Colt’s “Snake” revolvers are better than Smith & Wesson’s Model 29, the Dirty Harry “hand cannon.” The discussion runs along the same lines as to whether John Wayne or Clint Eastwood better define the American psyche, similar to the indeterminable bar-room arguments over whether a Ford or Chevy is better, or, in the lingo of this readership, a BMW 4 Series, an Audi A5, or Merc A45. Even here, 4 and 5 are once again the pivotal numbers, something of which the marketing teams of the automobile industry are surely well aware.

Throughout the long history of both the .45 and .44 rounds, in practical terms the many incarnations of the .44 probably wins the prize. On the other hand, the mythology of the .45 has an unstoppable power in popular imagination. The aura of the .45 round tends towards the semantic rather than the scientific, and the .44 is historically more experimental. If there is a choice, which there often is, choosing the right caliber for a pistol is not an easy decision. Based upon the mystique and quality of invention of the .44 or the .45 cartridges, it would have to be the .44. Then again, with a little more thought, maybe the .45 will do the job just fine. When push comes to shove, no one would ever know the difference. It’s the medium, not the message, which stops people in their tracks.

Review

By Ashley Hlebinsky

The debate between the .44 and .45 caliber in regards to comparative efficiency is deeply rooted. Comprehensively addressing this century old argument is a daunting task. It has been argued in terms of scientific advancement, historical significance, and, for most gun aficionados, a combination of the two. Benjamin Nicholson however has approached this debate using his background in design. With this perspective, he juxtaposes each caliber’s significance in both history and mythology.

Nicholson presents the history of cartridge design, from a round musket ball to the conically shaped bullet, which transitions into the self-contained metallic cartridge. It’s a complex evolution that is difficult to cover adequately in a book, let alone a paper. As a result, Nicholson must address, in a relatively short word count, a range of topics important to understanding cartridge history.

A design approach to cartridge comparison is insightful and one a technical expert may not consider in the same way that a person with an art and design background would. Nicholson covers a range of factors that can determine a caliber’s stopping power. Most notably, his introduction of the “design dance” illustrates just how many variables impact design. However, one for further consideration is not the design of the cartridge as it enters the chamber of a gun but how design can affect its intended target. A critical influence that determines stopping power is shot placement. In contemporary terms, a .22 caliber round in the back of the head is more lethal than a .45 caliber bullet in the arm. However from a historical perspective, even advancements of medicine can determine the degree of casualty. For example, the design of a round ball versus the conically shaped cartridge caused different levels of injury, which changed medical technology on the battlefield.

Nicholson infuses another layer into his cartridge assessment by looking at perception in popular culture. It, too, is a complicated study; one that could warrant its own paper. Nonetheless, the overall design approach on the .44 and .45 calibers is one that acknowledges the intricacies of ammunition. It certainly is becoming a topic of conversation as evolving cartridges, specifically new 9mm designs, are arguably rendering calibers like the .44 and .45 possibly obsolete for self-defense.

Notes

1

The “Colt 45” is the Colt Single Action Army revolver, Model of 1873, which used the .45 caliber Colt cartridge. The “44 Magnum” is the Smith & Wesson Model 29, that used the .44 Magnum cartridge.

2

The standard, non-specialized reference on historical and contemporary cartridge is Frank Barnes, Cartridges of the World, 14th Edition (Gun Digest, 2014). See, also, Michael Bussard 5th Ammo Encyclopedia (Blue Book Publications, Minneapolis, MN, 2014). For a good but slightly quirky book on small arms ammunition, read Herschel Logan, Cartridges: A Pictorial Digest of Small Arms Ammunition (New York, NY: Bonanza Books, 1959). Logan was a woodcut artist who illustrated rural life Kansas and a writer and avid cartridge collector. He combined these talents and made an easy to read, highly informative volume that he illustrated himself. It is worth noting that, of the hundreds of excellent books on firearms and ammunition, I know of only two that are published by university presses, an indication of the refusal of academia to acknowledge firearms a valid subject of inquiry. Museums do produce excellent catalogs and bulletins on specialized subjects, some of which are referred to below.

3

My thanks to Richard LaVen, who made a very careful reading of this text. He noted that Martha Phillips Gilson (1896−1993) spent much of the years 1916 – 1928 in the high Arctic. She was a very accomplished photographer, and her Arctic landscapes are still considered masterpieces. Martha was a practical cartridge collector and could identify almost anything common (from her era) at a glance. She explained, “In the high Arctic, money had no value. Cartridges were the common denominator of barter or commerce. In North America, the most commonly accepted were .44 – 40s. After that .30 – 30s or either .303, .30−40 Krag or .30−06. In Greenland, the Danish centerfires or maybe Jarmanns. In Spitsbergen and Arctic Norway and Sweden, 6.5×55. Finland and east, usually 7.62 Russian. Telling them apart was no more difficult than making change in pounds, shillings & pence.” Martha had little use for revolvers or their cartridges. “They won’t kill a polar bear. A Krag will, but only just”.

4

My thanks to Ken Meek, Museum Director of Woolaroc Museum, OK, for pointing out this table from the Dixie Gunworks website. Note that there is conflicting information about the weight of a .69 musket ball, which may skew this table. The most logical formula is that a .69 caliber ball of lead weighs 480 grains which equals 1 Troy ounce. An Avoirdupois ounce weighs 453.5 grains, which equals 1.03 ounces. The difference between Troy and Avoirdupois ounces is infinitesimal (much like between the .44 and 45 caliber bullets), but it counts when weighing out gold. If the .69 caliber bullet is related to the Troy weight, this table may be wrong. The authority on ammunition of this period is Berkeley Lewis, Small Arms and Ammunition in the United States Service, 1776 – 1865 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1956; Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 129, 1960), 219 – 231. On page 189, Lewis supplies a table for 1861 Cartridge Specifications in which the .69 caliber Musket uses a ball of .65 diameter weighing 412 grains or .94 ounces. The upshot of this is that weighing bullets is an inexact science as there were so many variables at play, but basically the Civil War .69 ball bullet weighed about an ounce.

5

Geoffrey Boothroyd, The Handgun (London, UK: Cassell, 1970). An excellent general survey of handgun history.

6

My thanks to Richard Waterman, who made a very careful reading of this essay on 07−19−15. He notes that the Minié ball was a French invention circa 1851 and was lethal up to four times the distance of a round ball. The illustration Bullets, 1850 – 1860, Wilcox has scores of profiles and sections of European bullets of this type. See Lewis, Small Arms and Ammunition in the United States Service, 1776 – 1865, plate 51.

7

After a year of careful negotiation, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago has approved the author’s course Guns: Myth & Manufacture, which will expand upon the theme of this essay.

8

An excellent essay on Flobert was written by Joseph T. Vorisek and published as The Flobert Gun (Brighton, MI: Cornell Publications, 1991).

9

Lewis, Small Arms Ammunition at the International Exposition Philadelphia, 1876, 3 – 8.

10

The Smith & Wesson Patent 27,933 dated April 17, 1860, Improvement in Filling Metallic Cartridges, places the mercury fulminate only in the rim, thus reducing swelling of the cartridge base that prevented the revolver’s cylinder from turning.

11

Outlines of the patents can be found in Report: Commissioner of Patents for the Year 1856, section XIX Firearms and Implements of War, and Parts thereof, including the Manufacture of Shot and Gunpowder. http://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/reportofcommis1856unit

12

Richard LaVen (personal correspondence, 07−19−15) pointed out Benjamin Tyler Henry’s contribution to cartridge design.

13

For the early development of Smith and Wesson pistols, see Roy G. Jinks, History of Smith & Wesson (Bienfeld, 1977), 16 – 57, and Jim Supica and Richard Nahas, Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson, 3rd edition (Gun Digest, 2006), 60 – 63.

14

The Smith & Wesson Number 3 went through several modifications. The last major change was the “Schofield” that hinged the top-latch on the frame rather than the barrel, which meant that a cavalryman could reload the revolver more easily whilst still holding the reins of his horse.

15

Richard LaVen (personal correspondence, 07−19−15).

16

Ibid.

17

Richard LaVen remarks, “The .44 Henry rimfire was really a .44 with a nominal bullet diameter of .438”. But the .44−40 Winchester uses .427” bullets, smaller in diameter than the S&W series and if you round up, it’s another .43. Once again, the .44 designation is another marketing ploy.”

18

Lewis, Small Arms Ammunition at the International Exposition Philadelphia, 1876, 42.

19

Brig. Gen. John Pitman, Ordnance Officer in the United States Army for thirty-nine years, assembled notebooks in which he drew, recorded, and added military reports concerning firearms and their ammunition. Facsimiles have been produced of his notebooks as The Pitman Notes on U.S. Martial Small Arms and Ammunition 1776 – 1933, Vol. Two Revolvers and Automatic Pistols, edited by Paul E. Klatt (Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1990). This volume illustrates most of the guns referred to in this essay and includes the full “Report of Board on Tests of Revolvers and Automatic Pistols” of 1907.

20

http://www.forgottenweapons.com/wp-content/uploads/manuals/1907pistoltrials.pdf

21

During WWI, when the US Army could not get enough Colt 1911 semi-auto pistols that used the new rimless .45 ACP round, Smith & Wesson invented the half-moon clip that allowed the rimless .45ACP to be used with their Hand Ejector swing out revolver and called it the M1917. It is an interesting moment in design, as a new cartridge is adapted for an existing firearm. This had been done before with the cap & ball percussion revolvers that were re-machined to accept metallic cartridges, but in this case only a tiny metal spring steel form was needed to solved the problem, in addition to shaving off 1÷16” from the cylinder to fit it in place.

22

Richard LaVen remarks, “The term “Magnum” comes from the wine industry and refers to the heavy glass bottles used for champagne. The bottles had to be stronger than standard to withstand the internal pressure of carbonated wine. IIRC, the term was introduced into ammunition by Holland & Holland (high quality British gun makers) about 1910 – 1912. They marketed ammunition with large powder charges and heavy (& stronger than normal) cartridge cases for the wealthy chaps who hunted African animals.”

Biographies

Benjamin Nicholson was educated at the Architectural Association, Cooper Union, and Cranbrook Academy and is now an associate professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He has been a guest teacher at SCI-Arc, Cornell, and the Universities of Edinburgh, London, Michigan, and Houston. Nicholson’s publications include Appliance House (Chicago Institute for Architecture and Urbanism/MIT Press, 1990), Thinking the Unthinkable House (Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, 1998), and The World: Who Wants It (Black Dog, 2004). He has exhibited at the Fondation Cartier, the Canadian Centre for Architecture, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and three times at the Venice Biennale. With interests ranging from agriculture to gun culture, primitive geometry to labyrinths, he recently co-edited (with Michelangelo Sabatino) the book Forms of Spirituality: Architecture & Landscape in New Harmony and is now working on Locked, Loaded & Liberal, a book about America’s gun culture. Email: bnicholson@saic.edu

Ashley Hlebinsky is Curator of the Cody Firearms Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming. She completed B.A. and M.A. degrees in American History and Museum Studies at the University of Delaware and first worked with firearms through a curatorial internship at the Soldiers and Sailors National Memorial Hall in Pittsburgh, PA. Before becoming Curator at Cody, Hlebinsky held a variety of positions there, including Buffalo Bill Research Fellow, Kinnucan Arms Chair Grant Recipient, intern, firearms assistant, and curatorial resident. Over several years, she worked closely with then Curator Warren Newman on exhibits, and she collaborated with the National Firearms Collection of the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC — for example, on the loan exhibition Journeying West: Distinctive Firearms from the Smithsonian Institution (2013−15). Hlebinsky is a consultant for firearms collections around the country, and her work has been profiled by the National Rifle Association as part of its Third Century NRA project. Email: AshleyH@centerofthewest.org