“The centre cannot hold,” writes W. B. Yeats while reflecting on the spiritual ruins of World War I. An archeology of military outposts across the twentieth century unearths a typology of early warning systems that trace the vector of a centre spinning into a “widening gyre.” Such an archeology outlines a series of architectural forms built to function on the edges of civilizations, concretizing a shift from a geometry focused on a centre to a topology of connections. Moving forward through time, traces remain in the form of a trinity of outposts based on three different types of modalities: the sonic in World War I, the visual in World War II, and the electromagnetic in the Cold War. Monument as Ruin (2015), which encapsulates the first two modalities, concludes a three-part research treatise on military architecture in which I have methodologically moved backward in time. In the initial project, my fieldwork Distant Early Warning (2009) engaged with the embedded landscape and the history of electromagnetic warfare in the latter half of the twentieth century. Particularly, Distant Early Warning investigated how the unique formal overlapping of the functional and structural elements of Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic radome foreshadowed networked warfare as an extension of game theory. The project focused on the geodesic radomes of the Arctic radar surveillance stations as the synecdoche of the Cold War’s development of networked warfare — an architecture that distributes its structural forces through a framework formally related to the communication network connecting the architecture. The current project, Monument as Ruin, retraces this methodology even farther back by focusing attention on two more, similarly extreme examples of military outposts but from before the Cold War: the centre of gravity in the Atlantikwall comprised of cement Nazi bunkers in World War II and the focus of the paraboloid in British experiments with cement sonic reflectors starting at the end of World War I. Seen as a completed series, the trilogy of twentieth century military outposts — due to their extreme design and construction — reveal the shift in values of a society: from a modernist centre to a contemporary decentralization.

The trajectory of modern military outposts unfolds according to the introduction of the third dimension of warfare — the development of flight that subsequently led to the addition of airplanes to the battlefield. Ancient warfare was at first one-dimensional (or odological, as in linear pathways) as military strategy followed the line of rivers and coastlines from port to port. Advancements in cartography and mobilization established a two-dimensional understanding of war with blocks of territory to conquer and defend. Three-dimensional warfare started to treat the earth, ocean, and air as spaces of penetration. In this modern theatre, two elements became important upon introducing aircraft: attack limitations were based on geodetic vectors of distance and not so much the landscape’s topography, and moreover, the speed of the enemy’s attack became exponentially faster. In order to defend against this new threat, Britain experimented with large cement paraboloid forms designed to collect and amplify the sound of noisy airplane engines. Built on the coast of the southeastern United Kingdom as a bulwark against continental invasion, the monoliths’ large concave dishes faced the English Channel, angled slightly upward into the clouds. According to fundamental physics, sound waves were expected to travel across the open ocean/landscape and bounce off the large reflective surface of the cement dish to be collected at a single point, the focus of the dish, and thus amplify the signal. A listener would be positioned at this exact point with either a stethoscope or a microphone, aiming to pick out an incoming bogey. Monumental in size, the structures were immovable, and, for most of the paraboloids, so was the resulting focus point for listening. (Experiments with later and larger reflectors involved moving the listener or positioning several listeners to attempt a direction-finding technique using spherical rather than paraboloid concaves.) Ultimately, the cement forms were a failure as they received too wide a bandwidth of sonic information: from ocean waves and traffic to wildlife and the elusive aircraft. The invention of radar, with its narrowed focus on metallic objects, quickly replaced these experiments before they were of any practical use, other than the establishment of a network protocol between outposts that was transferred to the Chain Home system. (Ironically, the first radar experiments by the British included bouncing a BBC radio signal off a bomber — a direct transfer from sound to electromagnetic information.) Today, the paraboloids stand guard over a Tarkovskian “Zone” of overgrown marshes, fields, and ruins. We no longer know if these monolithic sentinels are still listening. Perhaps, like the monolith of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, they are waiting to send out a cosmic signal at the destined geological period, although in our parallel universe, not at the advent of galactic homo sapiens but after the Anthropocene, when the Earth has cleansed itself of the dangerous mutations of humans.

Across the Channel a few decades later, the centre shifted from the focus of the paraboloid to the centre of gravity in bunker architecture. In his seminal exhibition and resulting book from 1975, Bunker Archeology, Paul Virilio points out that the uniqueness of the Atlantikwall’s cement forms consisted in their structural integrity derived not from a foundation but rather from their centre of mass. In contrast to traditional buildings constructed on pads or pillars aligning themselves with the Earth’s gravitational forces, what philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari would call “stratified space,” the bunker was a single cast object with deflecting curves and without windows — more like a monad. Consequently, if the earth was blown away under the bunker, instead of the building conventionally collapsing, it simply rolled upon the radius of its centre of gravity. With this movement, the concept of the centre in military architecture makes a slight shift: away from paraboloids with stationary centres of structure and perception, to bunkers that could tolerate movement and remain operational. Whether they move in the middle of battle among humans or in the battle against time itself, the bunkers embody the antithesis of artist Robert Smithson’s notion of architecture — instead of entropic time burying a shed, here the Earth itself has weathered away to reveal a cosmic starship. What remains is an evil relic of colonialism — either from an empire in the twentieth century or perhaps from when alien life first came to this planet millions of years ago.

Clarice Lispector. Água Viva. 1973

I stopped to drink cool water: the glass at this instant now is of thick faceted crystal and with thousands of glints of instants. Are objects halted time?

Pre-WWII Experimental Sonic Military Outpost Architecture, Dungeness, UK

Photo courtesy the author

Vincent Scully, Jr. Michelangelo's Fortification Drawings: A Study in the Reflex Diagonal. 1952

The rectangle and the simple circular rhythm, both calculable by numerical means, must give way to a more complex, dynamic system of interpenetrating diagonals. Space must not now be primarily enclosed as a volume-as it had been in even the powerful rocche of Francesco di Giorgio in the fifteenth century-but must, most actually, be created psychically along expanding diagonal fields of vision. The curve, where it appears, must accommodate itself to the dynamism of the diagonal. All the architectural elements then begin to move, the walls angle toward each other or away; at many of their points of intersection, in plan at least, voids must develop to allow circulation or vision.

Monument as Ruin (Installation Image)

Pigmented died cement sculptures, photographs, video installation and curated artefacts and art.

Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University

Photo courtesy the author

J.G. Ballard. The Drowned World. 1962

Far below them, the great dome of the planetarium hove out of the yellow light, reminding Kerans of some cosmic space vehicle marooned on Earth for millions of years and only now revealed by the sea.

World War II Generator Bunker, Atlantic Coast

Photo courtesy the author

Barbara M. Stafford. “Toward Romantic Landscape Perception: Illustrated Travels and the Rise of ‘Singularity’ as an Aesthetic Category.” Art Quarterly. 1977

The concept that true history is natural history emancipates the objects of nature from the government of man. For the idea of singularity it is significant . . . that geological phenomena--taken in their widest sense to include specimens from the mineral kingdom--constitute landscape forms in which natural history finds aesthetic expression. . . . The final stage in the historicizing of nature sees the products of history naturalized. In 1789, the German savant Samuel Witte-basing his conclusions on the writings of Desmarets, Duluc and Faujas de Saint-Fond-annexed the pyramids of Egypt for nature, declaring that they were basalt eruptions; he also identified the ruins of Persepolis, Baalbek, Palmyra, as well as the Temple of Jupiter at Agrigento and the Palace of the Incas in Peru, as lithic outcroppings.

World War II Bunker, Atlantic Coast

Photo courtesy the author

Andreas Huyssen. “Nostalgia for Ruins.” 2006

The work of Giovanni Battista Piranesi stands as one of the most radical articulations of the ruin problematic within modernity rather than after it. My interest in Piranesi and his ruins may well be itself nostalgic—nostalgic, that is, for a secular modernity that had a deep understanding of the ravages of time and the potential of the future, the destructiveness of domination and the tragic shortcomings of the present; an understanding of modernity that—from Piranesi and the romantics to Baudelaire, the historical avant-garde, and beyond—resulted in emphatic forms of critique, commitment, and compelling artistic expression.

An imaginary of ruins is central for any theory of modernity that wants to be more than the triumphalism of progress and democratization or longing for a past power of greatness. As against the optimism of Enlightenment thought, the modern imaginary of ruins remains conscious of the dark side of modernity, that which Diderot described as the inevitable “devastations of time” visible in ruins. It articulates the nightmare of the Enlightenment that all history might ultimately be overwhelmed by nature.

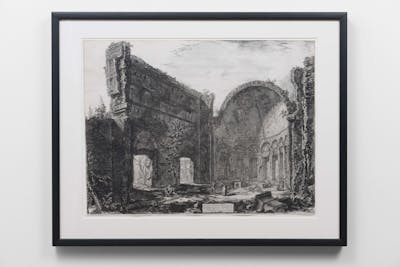

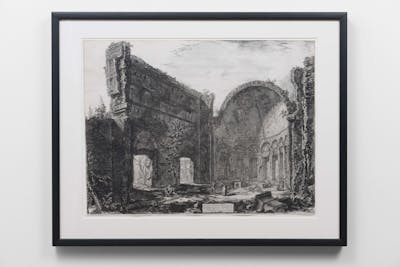

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Hadrian’s Villa: Apse of the so-called Hall of the Philosophers (1774)

In Monument as Ruin (Installation Image)

Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University

Collection: Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University

Photo courtesy Paul Litherland

W.G. Sebald. The Rings of Saturn. 1995

From a distance, the concrete shells, shored up with stones, in which for most of my lifetime hundreds of boffins had been at work devising new weapons systems, looked (probably because of their odd conical shape) like the tumuli in which the mighty and powerful were buried in prehistoric times with all their tools and utensils, silver and gold. My sense of being on ground intended for purposes transcending the profane was heightened by a number of buildings that resembled temples or pagodas, which seemed quite out of place in these military installations. But the closer I came to these ruins, the more any notion of a mysterious isle of the dead receded, and the more I imagined myself amidst the remains of our own civilization after its extinction in

some future catastrophe. To me too, as for some latter-day stranger ignorant of the nature of society wandering about among heaps of scrap metal and defunct machinery, the beings who had once lived and worked here were an enigma, as was the purpose of the primitive contraptions and fittings inside the bunkers, the iron rails under the ceilings, the hooks on the still partially tiled walls, the showerheads the sizes of plates, the ramps and soakaways. Where and in what time I truly was that day at Orfordness I cannot say, even now as I write these words.

Three types of parabolic sonic reflectors, Dungeness, UK

Photo courtesy the author

J.G. Ballard. The Terminal Beach. 1964

The series of weapons tests had fused the sand in layers, and the pseudo-geological strata condensed the brief epochs, microseconds in duration, of thermonuclear time. Typically the islands inverted the geologist’s maxim, The key to the past lies in islands was a fossil of time future, its bunkers and blockhouses illustrating the principle that the fossil record of life was one of armour and the exoskeleton.

The landscape is coded.

Entry points into the future=Levels in a spinal landscape=zones of significant time.

World War II Command and Communication Bunker, Atlantic Coast

Photo courtesy the author

Ernst Jünger. Storm of Steel. 1924

The particular character of fortified works does not appear with as much impact when one dwells in them. This character became vivid only when I was reviewing block 14 of the customs point at Greffern, which its occupants had deserted. When I had after much effort succeeded in opening the enormous iron door and had gone down into the concrete crypt, I found myself alone with the machine guns, the ventilators, the hand grenades, and the munitions, and I held my breath. Sometimes a drop of water would fall from the ceiling or the sector telephone would ring in various ways. It was only here that I recognized the place as the seat of cyclops who were expert in metal works but who do not have the inner eye, just as sometimes in museums you can ascertain the meaning of certain works more clearly than those craftsmen who made them and who used them at length. Thus was I, as if inside a pyramid or in the depths of catacombs, faced with the genius of time that I construed as an idol, without the animated reflection of technical finesse and whose enormous power I understood perfectly. Moreover, the extremely crushed and chelonian form of these constructions recall Aztec architecture, and not only superficially; what was there the sun is here the intellect and both are in contact with blood, with the powers of death.

Interior World War II Bunker, Atlantic Coast

Photo courtesy the author

Michel Foucault. The Archeology of Knowledge & The Discourse on Language. 1971

Archaeology tries to define not the thoughts, representations, images, themes, preoccupations that are concealed or revealed in discourses; but those discourses themselves, those discourses as practices obeying certain rules. It does not treat discourse as document, as a sign of something else, as an element that ought to be transparent, but whose unfortunate opacity must often be pierced if one is to reach at last the depth of the essential in the place in which it is held in reserve; it is concerned with discourse in its own volume, as a monument. It is not an interpretative discipline: it does not seek another, better-hidden discourse. It refuses to be "allegorical."

200ft. Parabolic Wall, Dungeness, UK

Photo courtesy the author

Paul Virilio. Bunker Archeology. 1975

A long history was curled up here. These concrete blocks were in fact the final throw-offs of the history of frontiers, from the Roman limes to the Great Wall of China; the bunkers, as ultimate military surface architecture, had shipwrecked at lands’ limits, at the precise moment of the sky’s arrival in war; they marked off the horizontal littoral, the continental limit. History had changed course one final time before jumping into the immensity of aerial space.

While most buildings are embanked in the terrain by their foundations, the casemate is devoid of any, aside from its center of gravity, which explains its possibility for limited movement when the surrounding ground undergoes the impact of projectiles. This is also the reason for our frequent discovery of certain upturned or tilted works, without serious damage.

World War II Artillery Storage Bunker, Atlantic Coast

Photo courtesy the author

W.G. Sebald. Austerlitz. 2001

No one today, said Austerlitz, has the faintest idea of the boundless amount of theoretical writings on the building of fortifications, of the fantastic nature of the geometric, trigonometric, and logistical calculations they record, of the inflated excesses of the professional vocabulary of fortification and siege-craft, no one now understands its simplest terms, escape and courtine, faussebraie, réduit, and glacis.

World War II Artillery Bunker, Atlantic Coast

Photo courtesy the author

Albert Speer. Inside the Third Reich. 1969

Hitler planned these defensive installations down to the smallest details. He even designed the various types of bunkers and pillboxes, usually in the hours of the night. The designs were only sketches, but they were executed with precision. Never sparing in self-praise, he often remarked that his designs ideally met all the requirements of a frontline soldier. They were adopted almost without revision by the general of the Corps of Engineers.

World War II Artillery Bunker, Atlantic Coast

Photo courtesy the author

Carl von Clausewitz. On War. 1816–30

The general action may therefore be regarded as war concentrated, as the centre of gravity of the whole war or campaign. As the sun’s rays unite in the focus of the concave mirror in a perfect image, and in the fullness of their heat; so the forces and circumstances of war, unite in a focus in the great battle for one concentrated utmost effort.

Concave Paraboloid Reflector, Dungeness, UK

Photo courtesy the author

Eyal Weizman et al. Forensis. 2014

In modern languages, the singular ruin conserves a meaning very close to its Latin origin—ruina, "fall," ”co|lapse.” To designate the material traces of that event, the indefinite plural ruins is still preferred. This nuance too we inherited from Latin which, in coining the two-sided term, foresaw the stakes at its core and laid down the ground for a timeless problem: ruins can never be grasped as a single entity; made of uncountable links to pasts and futures, their hazy contours always refer to a plurality of potentials.

200ft. Parabolic Wall, Dungeness, UK

Photo courtesy the author

Robert Smithson. “The Iconography of Desolation.” c.1962

The Fourth Dimension is simply the ruins of the Third Dimension.

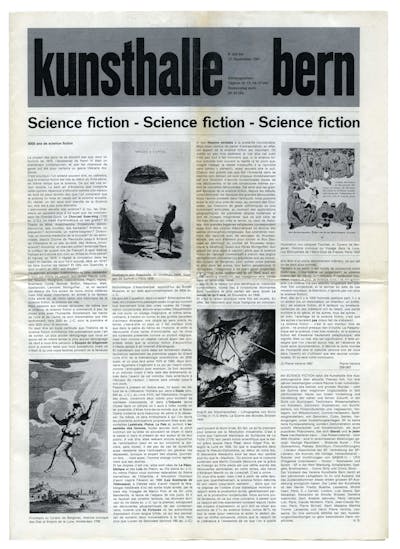

Harald Szeemann

Science Fiction (Kunsthalle Bern) 1967

Broadsheet newspaper

In Monument as Ruin (Installation Image)

Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University

Photo courtesy the author

Thomas Pynchon. Gravity’s Rainbow. 1973

One night, in the rain, their laager stops for the night at a deserted research station, where the Germans, close to the end of the War, were developing a sonic death-mirror. Tall paraboloids of concrete are staggered, white and monolithic, across the plain. The idea was to set off an explosion in front of the paraboloid, at the exact focal point. The concrete mirror would then throw back a perfect shock wave to destroy anything in its path. Thousands of guinea pigs, dogs and cows were experimentally blasted to death here—reams of death-curve data were compiled. But the project was a lemon. Only good at short range, and you rapidly came to a falloff point where the amount of explosives needed might as well be deployed some other way. Fog, wind, hardly visible ripples or snags in the terrain, anything less than perfect conditions, could ruin the shock wave’s deadly shape. Still, Enzian can envision a war, a place for them, “a desert. Lure your enemy to a desert. The Kalahari. Wait for the wind to die.”

The Second Coming (video installation with 4m cement sonic reflector)

in Monument as Ruin (Installation Image)

Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University

Photo courtesy the author

Friedrich Kittler. Discourse Networks 1800/1900. 1985

Information technology is always already strategy or war.

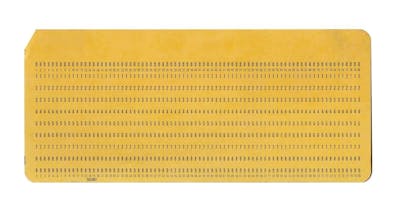

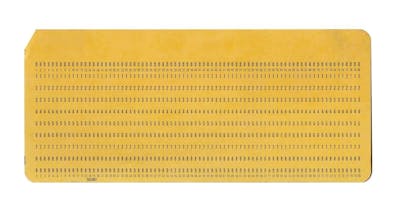

IBM 5081 punch card from United States Air Force base, Thule, Greenland, used for controlling computer at Distant Early Warning radar outpost.

In Monument as Ruin (Installation Image)

Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University

Photo courtesy the author

Review

By Matthew Flintham

As a photographic and theoretical study of Nazi bunkers from the Atlantikwall, Paul Virilio’s seminal book Bunker Archaeology (1975)1 is surely the Ur-text for current artistic and speculative engagements with defensive architecture from across the twentieth century.2 Charles Stankievech’s current collection of works and artifacts, Monument as Ruin (2015), commissioned for the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, is no exception, clearly aligning itself with Virilio’s conceptions of the military ruin as a cryptic marker for the evolution of martial space.

Monument as Ruin completes a trilogy of work relating to the expanding, decentered, and dematerializing sphere of military influence. The Dew Project (2009), for example, draws on the geodesic dome as a means to studying Cold War early warning systems and the emergence of Network Centric Warfare (NCW), and The Soniferous Æther of The Land Beyond The Land Beyond (2014) stunningly describes the architecture and technologies of a remote Signals Intelligence station in extreme northern Canada.

While both these works interpret the manipulation of the electromagnetic spectrum for early warning and eavesdropping purposes, Monument as Ruin steps back to re-engage with the materiality of warfare, with concrete as a medium of frontier defense and surveillance. Indeed, Stankievech’s commitment to understanding the material properties of concrete is confirmed by the presence within the exhibition of three scaled reproductions of Atlantikwall bunkers, L’Aigle (Fragment 649, 636, 606). These “fragments” are accompanied in the same room by three smaller objects of extraterrestrial origin, meteorites which allude to a cosmic or, perhaps, an eschatological violence infinitely greater than our own limited attempts. Here we also find an unfolded copy of A. E Van Vogt’s 1939 novella, Black Destroyer. The title alone is enough to suggest a reckoning with a cosmic intelligence, an architect of cataclysmic destruction. Two large photographs by Stankievech, Monument as Ruin (Wreck), a giant casemate pitched improbably on a beach, and Monument as Ruin (Earth), an immense parabolic sound reflector seen from behind, also allude to the military other, whose “aesthetic features are sui generis,“3 utterly alien (at their time of conception) to architectural convention or social function. However, the presence nearby of an etching by Piranesi, Hadrian’s Villa: Apse of the so-called Hall of the Philosophers (1774)—which bears a striking resemblance to the sound capturing architecture of the “Earth” photograph — is clearly an attempt by Stankievech to position military architecture within a deeper, ancient heritage.4

A scaled down, concrete reproduction of the British WW1 sound reflector dominates the adjacent space. Originally built to collect and amplify the otherwise inaudible sounds of distant aircraft across the English Channel, Stankievech’s version receives the sounds of multireedist composer Colin Stetson. This is military technology designed in the cold panic of an emerging aerial, vertical warfare, but repurposed by Stankievech to enhance it’s sonic, collaborative potential — a receiver and reflector of cultural research and production.

As a collection of curated works in situ, Monument as Ruin operates as an observatory, a platform of stasis from which we might assess the material and immaterial dimensions of human militarism. However, with Stankievech, we are also adrift in the abyss of deep time, witnessing the redeployment of ancient minerals in the service of warfare, their subsequent obsolescence and degradation, and also the transmissions of invisible emissions that will echo through space into a distant, non-human future.

Notes

1

Paul Virilio, Bunker Archaeology, translated by George Collins (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1994). First published as Bunker archéologie (Paris, France: Centre Georges Pompidou, Centre de création industrielle, 1975).

2

See, for example, Allora & Calzadilla’s sculpture/performance Clamor (2006), which fuses bunker architecture, rock formations, and musical instruments accompanied by a cacophonous soundtrack of militaristic music. See also Jane and Louise Wilson’s film Sealander (2006) and their photographs of Atlantic Wall bunkers.

3

Paul Hirst, Space and Power: Politics, War, and Architecture (Cambridge, MA: Polity, 2005), 215.

4

Stankievech is correct, military architecture has a lost or “secret” history which is evident in the Organisation Todt’s Nazi bunkers but stretches back via the great crystalline trace italienne fortifications of the 17th and 18th centuries and the great castles of Europe, the Middle East, and Asia to the work of Vitruvius himself in the Roman era.

- Tags

- technologyhistoryplacewarlandscape

Biographies

Charles Stankievech is an artist and writer whose research explores the notion of “fieldwork” in the embedded landscape, the military industrial complex, and the history of technology. He has exhibited work and lectured internationally at leading venues, including the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen; the Palais de Tokyo, Paris; HKW: Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin; TBA21: Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, Vienna; MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA; the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal; Documenta 13, Kassel, and the Venice Architecture, Venice Art, SITE Santa Fe, and Berlin Biennials. He is co-director of the art and theory press K. in Berlin and an editor for Afterall (London). He is currently Director of Visual Studies in the Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design at the University of Toronto. Email: charles@stankievech.net

Matthew Flintham is an artist and writer specializing in the hidden geographies of militarization, security and surveillance. He has a B.A. (Hons) in Fine Art from Central Saint Martins, an M.A. in Humanities and Cultural Studies from the London Consortium, and a Ph.D. in Visual Communications from the Royal College of Art. His work intersects academic and arts practices, exploring speculative relationships between architecture, power, and place and the possibilities for arts methods to reveal hidden or immaterial relations in the landscape. During 2014, he was Leverhulme Artist-in-Residence in the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology (GPS) at Newcastle University, and he is currently Research Associate at the Centre for Architecture and the Visual Arts (CAVA) at Liverpool University. His research has been featured in Militarized Landscapes: From Gettysburg to Salisbury Plain (Continuum, 2010), Tate Papers 17, and Emerging Landscapes: Between Production and Representation (Ashgate, 2014). He lives in London. Email: matthewflintham@hotmail.com