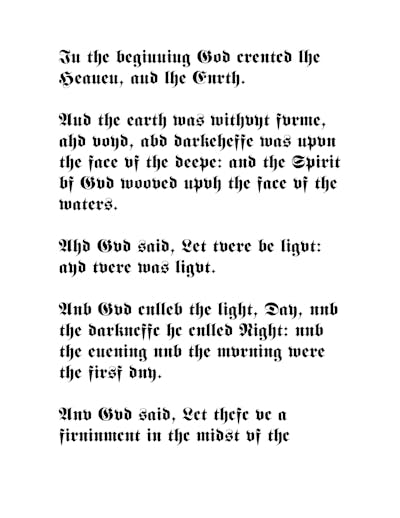

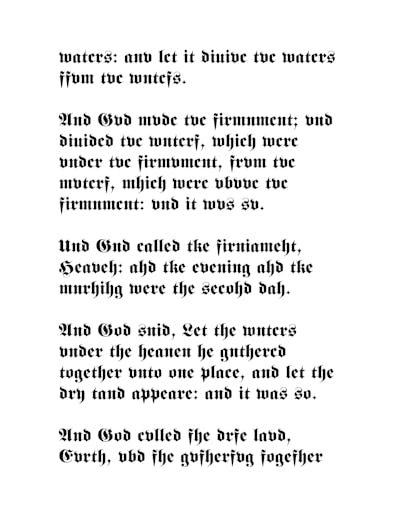

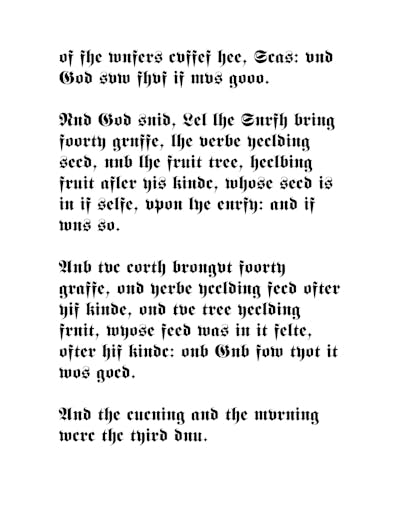

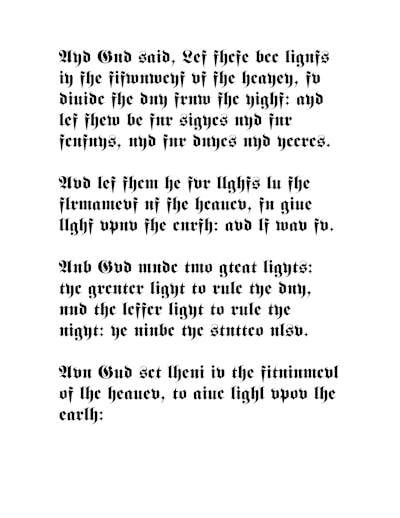

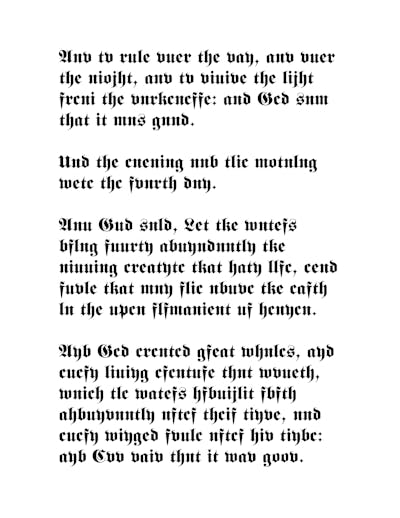

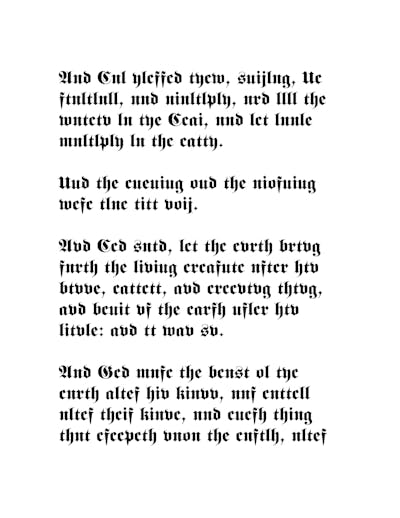

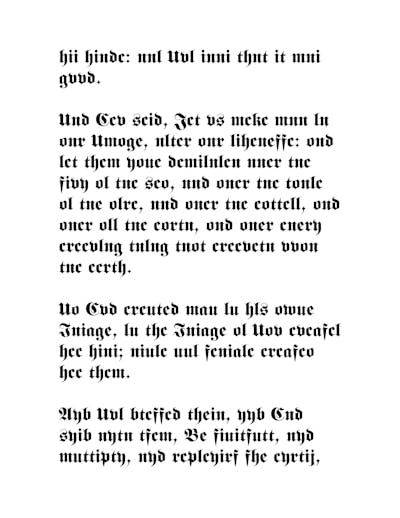

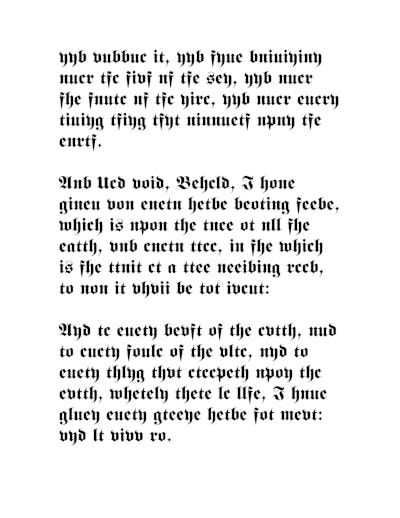

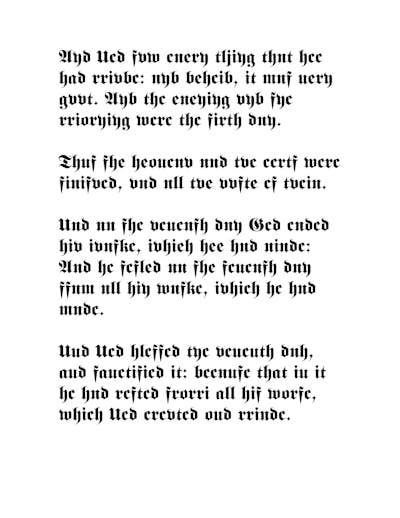

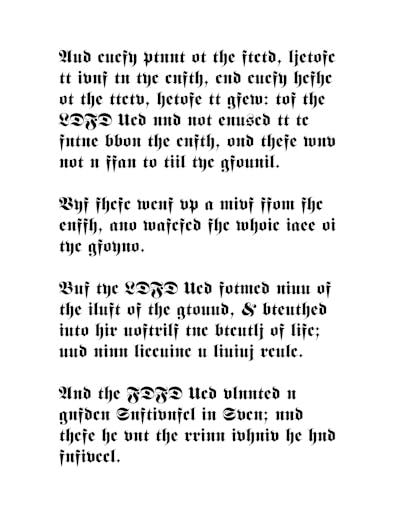

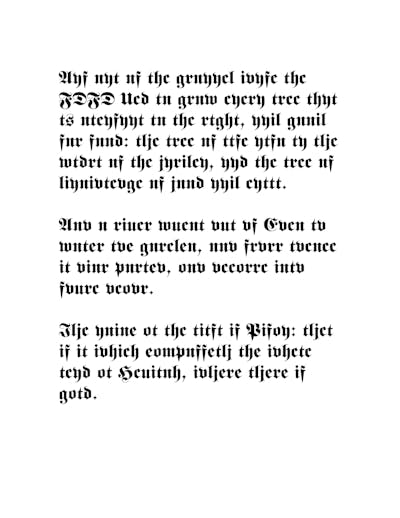

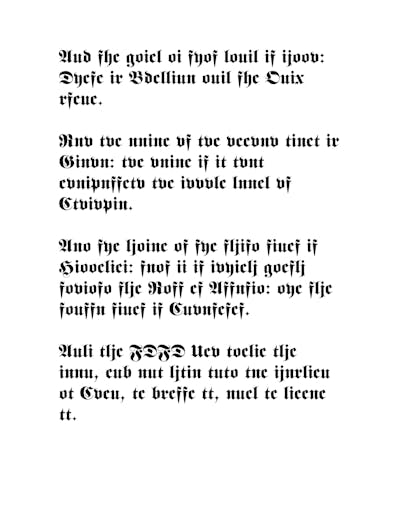

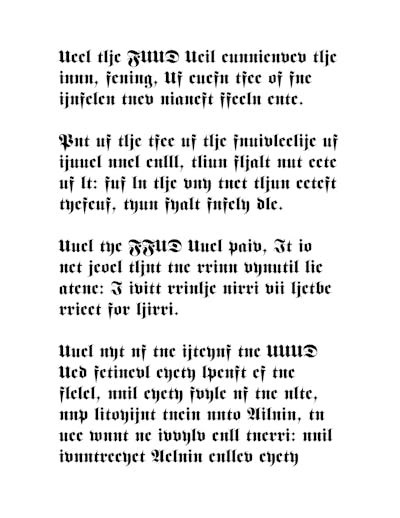

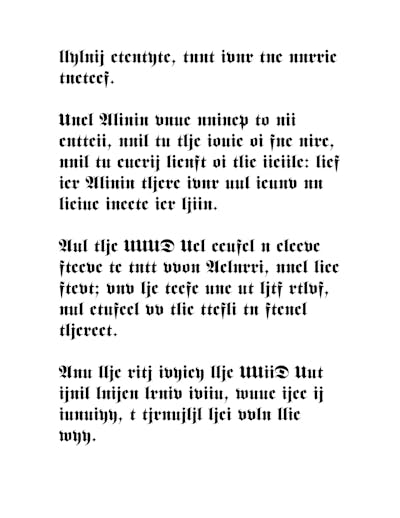

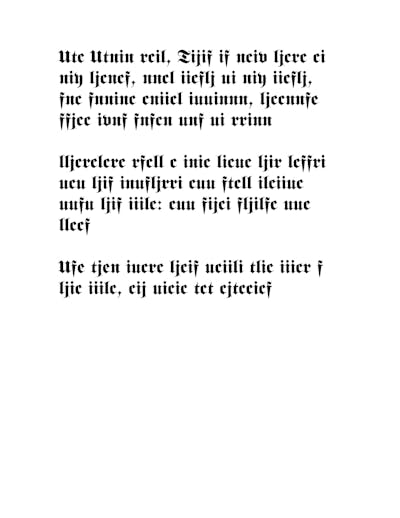

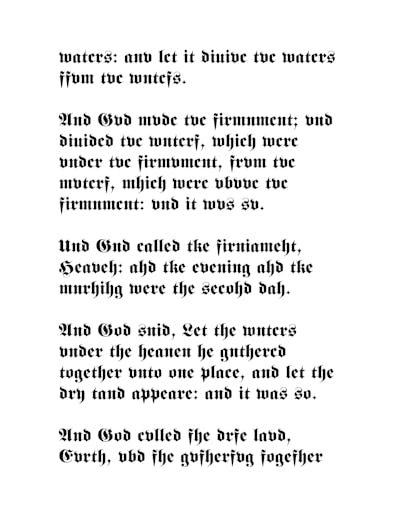

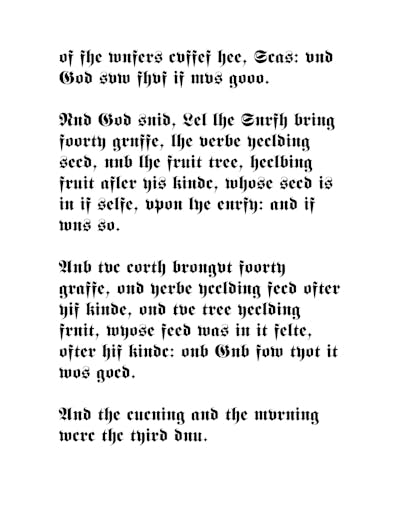

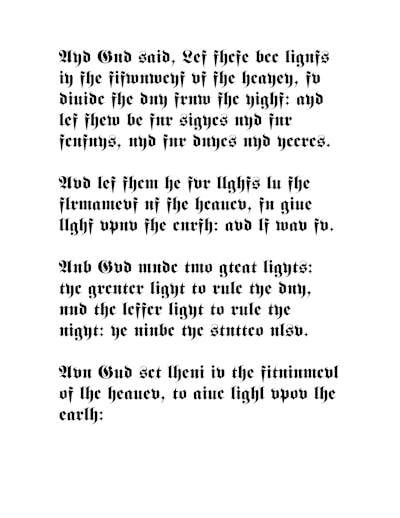

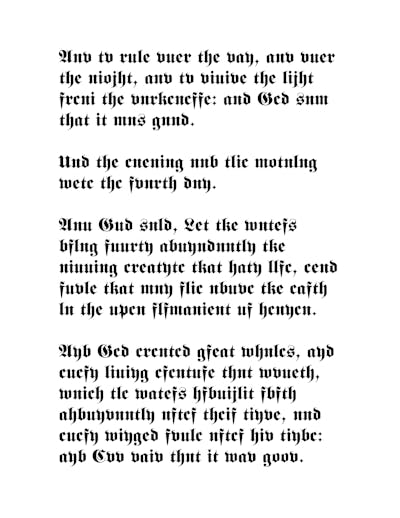

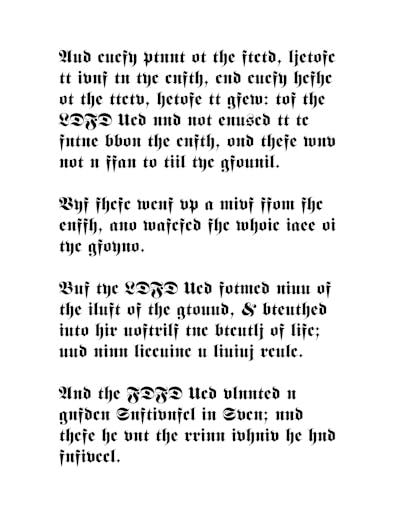

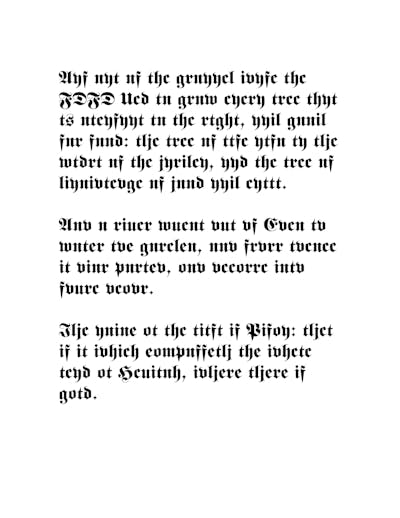

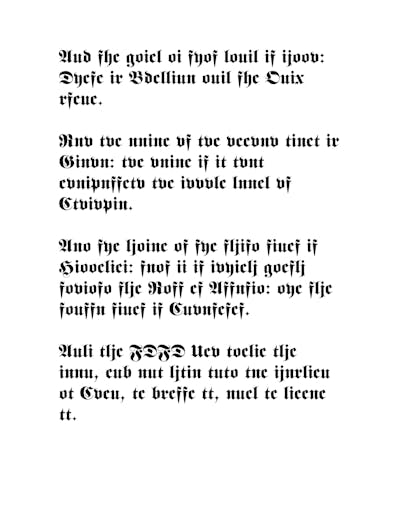

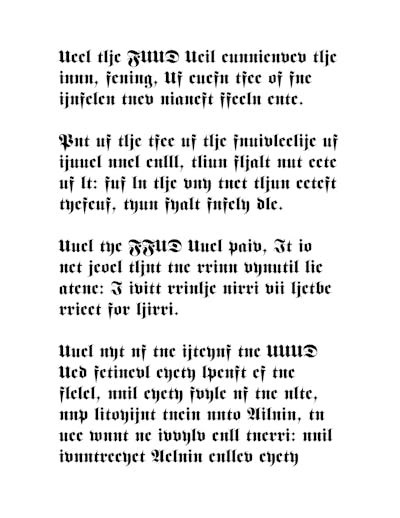

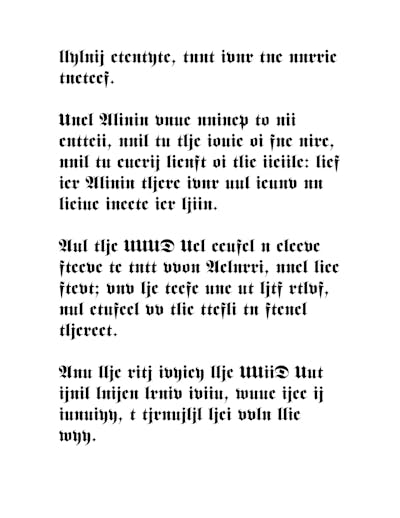

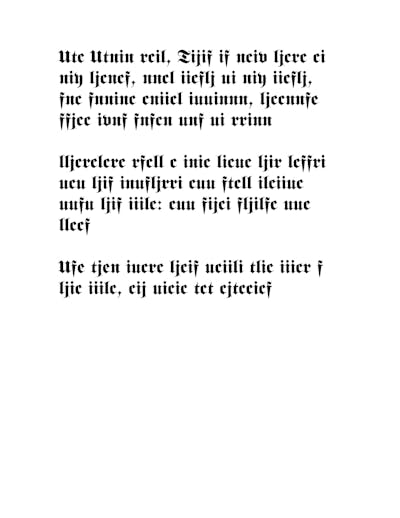

This work uses the increasing illegibility of a text set in a black-letter typeface to conceptually represent the experience of reading print in a very dark, interior space without ambient external light. We rarely experience environments like this today, but before the era of gas or electric light, such environments were quite common: at night, one often read and misread under the light of a rapidly dimming candle or fire, and if there was no moon, or a cloudy night sky, the exterior provided no light at all.

“Reading in a Very Dark Room…” continues the exploration I conducted in the project “Reading Hollywood in the Smog.” Both projects explore forms of environmental and spatial representation solely through alphanumerical characters versus more mimetic and literal chromatic and contrast-based forms of representing atmospheres, lighting, smog, and other environmental effects. Both works also make new writing out of existing texts through this form of environmental representation and translation.

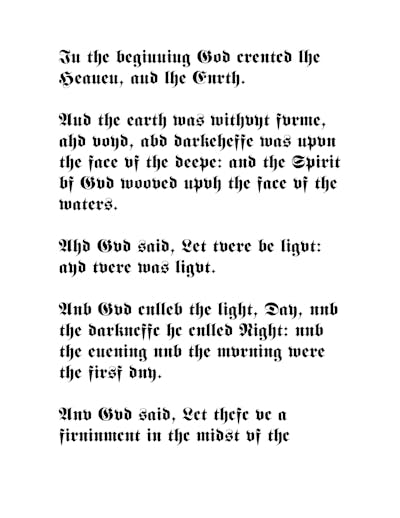

I could have chosen any early modern, English-language text to represent the effects for reading in a very dark room, but I settled on the somewhat controversial choice of the 1611 King James Bible for several reasons. This was one of the more widely available, printed, English-language texts in the mid- to late-17th century. Additionally, many contemporary English-language readers are familiar with its language, so that my manipulations of it are more legible to the reader (a crucial consideration). Equally useful is the character of the language of the 1611 King James Bible, which has a historicist quality: it reads as if from another era — better aligning with the environmental history that interested me. Finally, the work was set in black-letter (with Arabic numerals), which presents interesting issues around type and its legibility and perception as explained below.

After examining 19th-century scientific research on the ways that readers misidentified blackletter type under highly reduced forms of visibility, I wrote a computer script that rerepresented the appearance of the original text as it might initially appear under near darkness. The letter confusions caused by inadequate lighting are interesting, and many are unlike those found in a Roman alphabet. According to 19th-century research, a black-letter “a” will often resemble “n” or “o”; “d” can take on the appearance of “h,” “b,” or “o”; “i” can look like “t” or “f”; “n” and “y” are often confused, among a whole host of other misidentifications. The misidentifications work in reverse as well; thus, if readers squint their eyes or encounter the text I created in a nearly dark room, the book becomes more legible. Most interesting is that, in the original 1611 printing, the publisher actually relied on these optical effects. He often swapped similar looking letters of black-letter type — particularly “u” and “v” — to better fit lines of text on the page. In other words, the publisher relied on the type of letter confusions that govern the process that I used in this work.

Finally, this work is an effort at environmental translation — the translation of text from one environment to another. We understand how texts might be translated from one language to another, but environmental translation opens entirely new possibilities for texts as forms of spatial representation.

Review

By Adrian Johns

The most powerful image of reading in the seventeenth century is one of reading by artificial light. “Behold now this vast City,” John Milton commanded the parliamentarians of the period. At a time of civil war, the city was full of workshops turning out weapons to defend against King Charles I’s armies; but more remarkable were the citizens themselves, “sitting by their studious lamps,… reading, trying all things, assenting to the force of reason and convincement.” This was Milton’s exhilarating ideal of the Christian commonwealth. Every well-affected citizen must burn the midnight oil, poring over the latest pamphlets and treatises. Doing so was not only a right, but a duty. And it was simply the reality of the time that most of this work would be done after dusk, when their workshops were shuttered. It was a mundane irony of early modernity that enlightenment took place in darkness.

But reading by candlelight is hard. And it is all the harder when what one is looking at is a page produced not by a laser-printer but by handicraft. Characters are liable to be transposed, inverted, damaged, or omitted altogether, sometimes en masse. And this too was the reality for Milton’s readers. They had to turn their pages to catch the light; they squinted at the lines on the paper, hoping to arrive at accuracy by distortion. They conjectured at true readings by making semi-conscious tactical misreadings of what lay before them. It was tough to do. Yet, people did it routinely, day in and day out.

What this implies is that reading itself — the basic act of parsing letters on a page to manifest some kind of meaning — required the active exercise of the imagination. Exactly how active, though? This was a matter for intense debate. There was no more precious principle in Protestant Europe than that of the lay reading of Scripture. But at a time of rampant religious radicalism, readers could claim warrant for all kinds of beliefs and actions in terms of experiences they had undergone when alone and face-to-face with Scripture under lamplight. The most prevalent criticism of such claims was that they were the product of reading with a poorly controlled imagination. All readers must indeed respond actively to the page, but they must at the same time take great care that their responses be disciplined, ruly, moderate. Learning to identify such readings was a central part of being a good Christian subject.

The question of how to read in semi-darkness — or, to put it another way, the question of how to recognize that what one has produced is indeed a reading—is therefore a pivotal one. To reproduce by digital processing the degrees and kinds of “misreading,” as David Gissen has done here, is a fascinating and suggestive experiment. It does indeed imply that reading is an “environmental” practice, in the richest possible sense of that word. Which in turn means that our own reading practices ought to be understood in terms of an environmental history. That’s a project that no historian has yet thought to undertake.

It’s especially fitting that Gissen has chosen black-letter for his example, because it implies a further step that could be taken — one that is as suggestive for the future of reading as his experiment is about its past. What if we ask the computer not only to reproduce the different degradations to which letters were prone, but to attempt its own reading? For it is notorious among historians of the period that computers are inept when it comes to decoding black-letter. Optical Character Recognition algorithms have been used now to produce machine-searchable texts for many seventeenth-century books. They can be very error-prone, but, in our counterpart of dark reading, they are basically parsable if you know what kinds of errors the algorithms typically make. But if you look for the plain-text rendering of the 1611 Bible in the standard massive database of such things, you will not find it. The reason for this extraordinary omission is that computers are not capable — yet — of rendering the variety present in even a single black-letter page into raw ASCII. And the only way they will ever become capable, experts say, is by being laboriously “trained” through guided exposure to many, many such pages, with attentive humans correcting their errors as they go. Only in this way may they eventually develop the insight — the “controlled imagination” — to distinguish a plausible reading (“God created the heaven and the Earth”) from one implausible in any culture we are ever likely to encounter (“God crentcd lhe Heaueu, aud lhe Enrth”). In an age when Big Data is often hailed as omniscient, it is strangely reassuring to find that our most powerful algorithms remain less capable than any competent reader of Shakespeare’s age — and that to do any better they will have to ask us for help.

By Herbert Marder

Simone Weil says that the hard sciences like physics that rely on increasingly precise measurements create the miracles of modern technology (one physicist compares the iPad to the great cathedrals) but at the cost of an “infinite error.” David Gissen’s experiment in “environmental translation” raises the question: What is being measured? The dim lighting at night in 17th-century rooms is a fact; it leads to “a garden of forking paths.” (Jorge Luis Borges) Other questions come to mind about making an “environmental translation”: How common was the ability to read? Who read, who had access to books, to the King James Bible? And about candles: How much did they cost? Who had leisure and education — i.e., was rich enough to read at night? Monks in the monasteries were the preservers of literate culture. Some aristocrats and others went to universities. What did they learn there, and what do the histories and literature we read now — e.g., the plays of Shakespeare — tell us about the 17th-century environment?

As for the King James Bible, how well did different classes of readers know Genesis? A few might know all of it by heart. But slow down…the contemporary literary critic Harold Bloom, who combines a photographic memory with childhood studies based on the Hebrew Torah, might have a different way of reading the translation. Were there polymath readers in the 17th century? And again…Helen Vendler, in “The Art of Shakespeare’s Sonnets,” gives photographic reproductions of the 1609 quarto “Sonnets,” along with a modernized version. Reading the most famous sonnets in the English language as a 17th-century reader would have read them, one knows instantly that we are in a different world. The fascinating question about lighting and “environmental translation” can be used to measure something with some degree of precision. Or it can be used as a garden of forking paths, that is, an ingenious provocation or an invitation, in John Cage’s terms, to “purposeless play.”

- Tags

- religontechnologyhistoryliteraturereadingenvironmental translation

Biographies

David Gissen is a historian, theorist, curator, and critic whose work examines histories and theories of architecture, landscapes, environments, and cities. His recent work focuses on developing a novel concept of nature in architectural thought and experimental forms of architectural historical practice. Gissen is the author of Manhattan Atmospheres: Architecture, the Interior Environment, and Urban Crisis (University of Minnesota Press, 2014) and Subnature: Architecture’s Other Environments (Princeton Architectural Press, 2009), and he edited of the “Territory” issue of AD Journal (2010) and Big and Green (Princeton Architectural Press, 2003). His essays have been published in journals such as AA Files, Cabinet, Grey Room, Log, Quaderns, and Thresholds, as well as a wide range of magazines, newspapers, blogs, and books. His curatorial and experimental historical work has been staged at the Museum of the City of New York, the National Building Museum, the Yale University Architecture Gallery, the Toronto Free Gallery, and the Canadian Centre for Architecture, among other venues. Gissen is currently an associate professor at the California College of the Arts. Email: dgissen@cca.edu

Adrian Johns is the author of The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making (University of Chicago Press, 1998), Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates (University of Chicago Press, 2009), and Death of a Pirate: British Radio and the Making of the Information Age (W. W. Norton & Co, 2011). He has been teaching and writing about the histories of print, information, and science since the early 1990s. Educated at Cambridge, Johns has taught at Caltech; the University of California, San Diego; and the University of Chicago, where he is currently Allan Grant Maclear Professor of History. He has received awards from the Guggenheim Foundation, the ACLS, and other distinguished bodies. Johns is now at work on two books, the first a history of the policing of information and the second a new account of the scientific revolution in early modern Europe. Email: johns@uchicago.edu

Herbert Marder is a poet, painter, and emeritus professor of English at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he taught literature and rhetoric. He is the author of Feminism and Art: A Study of Virginia Woolf (University of Chicago Press, 1968) and The Measure of Life: Virginia Woolf’s Last Years (Cornell University Press, 2000). In 1970, Marder and his wife, singer Norma Marder, co-founded the New Verbal Workshop, an experimental ensemble conceived as a platform for exploring “speechmusic.” For more than a decade, the New Verbal Workshop brought together an evolving personnel of trained performers and amateurs, who developed a repertoire of original compositions through collective improvisation. The ensemble also performed experimental music by distinguished contemporary composers Kenneth Gaburo and Ben Johnston. Email: marder@illinois.edu