Shop and Save supermarket sign, Lemay Ferry Road, St. Louis County. Photograph by the author, 2017.

Once this place was so easy to know. Before Michael Brown, before Kate Chopin, before Jonathan Franzen, before William Burroughs, before David R. Francis, before Leroy Bundy, before Joseph Wingate Folk went after the “Big Cinch” capitalist syndicate, before Pontiac commiserated with French officers at a tavern, before Frankie Freeman was able to whisper to Lyndon B. Johnson, before Kay Drey and boxes of requested government documents, before Shelley, and Kraemer, before Charles Guggenheim triumphalized the Gateway Arch, before Minoru Yamasaki gave the city both its celebrated port of entry and its tragic modern symbol, before Nathaniel Lyon contained the Confederate mob, before Harry Turner drowned himself on Christmas day, before Mary Meachum led runaway slaves across the river, before the wealthy of the city formed a posse and shot striking streetcar engineers, before Archie Blaine broke on supporting the bulldozing of his own neighborhood, before Robert E. Lee manipulated our river to keep St. Louis alive, before St. Louis Cardinals fans left their night game to assault black swimmers at Fairground Park, before Joe Edwards built his trolley, before Edqar Queeny set into motion the company capable of developing Agent Orange, before Thomas Stearns Eliot packed his bags, before the Cahokian elite built the palisade to keep out the riffraff or the water, before, before, before.

Before power, or empire, ever set upon this place?

The Chief Pontiac VFW in Cahokia, Illinois. Photograph by the author, 2016.

Before humans? Which part — the part that has no part? Or the part that claims its interests constitute the interests of the whole?

The dream of the river that runs through our city may be freedom from the strange parade of settlement — the tortuous, inflicted and inflected presences of people across its high and low lands. But such a condition is unknowable, past or future. We are left to dwell in-between. Staying with the trouble, as Donna Haraway counsels, seems like no choice, but a preternatural edict.1 There’s nowhere else to go.

Are we left in the Anthropocene?

If so, we may not be any farther along than we have been since Cahokia rose many centuries ago. We just now carry with us a long European heritage of puritanism that has not been expiated. Sometimes it seems that we chronicle the actions of humans here and across the globe to shame ourselves, as if history were a fundamentally moral construction. The past doesn’t actually give a damn about right and wrong, but it gives anyone who does an arsenal of evidence.

Vacant houses on Cass Avenue in St. Louis. Photograph by the author, 2018.

We look at landscape as evidence with which to explain the present, the Anthropocene or whenever this is. And I go with whenever because I don’t think time is as short as a word tethered to the accelerated nomos and habitus of humans.

Perhaps we need to start naming what is about to happen when we look at what has already happened.

Lost on the interpretive trail, Valmeyer, Illinois. Photograph by the author, 2017.

Landscapes seem urgent or precarious now, but they are deceiving us. They want us to think they are one thing when, in fact, they are another. They naturalize records of power and abuse, sending detectives tracking always right back to the present. We call landscapes unstable in this time, but, in truth, they are one of the most stable signifiers that the forces of capitalism, racism, and imperialism have at their disposal. It’s easier to shape the land than to change the minds of people, or kill them off. The new shape arrests time, abridging the moment between the wound and the healing. Instead, the wounds are dissolved into junk spaces that few question as evidence of what comes next, some question as evidence of what came before, and most people reconcile with a view of what comes now that renders any horizon of action invisible.

The monuments tell us big lies, so we look closely at the terrain of everyday life. We hit the parking lots, the dying shopping malls, the places between fences, the ghettoes, the slag heaps and the ruderal fields. Like Orpheus, for a while, we won’t look behind but ahead, at the mundane, fearing that we will kill beauty (or that beauty will kill us, or that beauty no longer exists according to years of pessimistic theory). Then, like the Angel of History, we turn around, finding only more of the mundane, but we render it also a monument, a frozen and dead thing.

Every coincidence tempts us with the lure of significance. This lure dampens time, flattens it into a circle, we arrive only where we start.

The dead-end block, near where a famous musician had his first house, in the middle of an urban renewal project, three blocks from a big This and not far from a That and you know what that has to mean…

But do we know what that has to mean?

In Plain Sight by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Laura Kurgan, and Robert Gerard Pietrusko, with Columbia Center for Spatial Research. Photograph by the author at Wrightwood 659 Gallery, Chicago, Illinois, 2019.

Do we know anything at all when we make such surmises, or are we feebly lurching toward a pattern recognition our brains instill because the condition always worse than death is to be completely lost?

Maybe being lost is not so bad after all. Being found seems pretty dull. There are Instagram feeds devoted to so many aspects of ordinary landscapes that the photographs sometimes seem to be not images of other places, but other images or at least other influences. Skidding by at a split-second view, they signify only what we can already envision them to signify, because we aren’t inhabiting the images let alone the subjects they present. Mass media kills us by making us tourists.

The words of artist Claire Pentecost are better than mine here: “The tourism of everyday life may include signifiers of place, but paradoxically, the overall effect is to make us forget that we live in a place, a place called Earth.”2 Affect sublimates what we truly seek to change.

How do we break the flat plane of time, and move past naming it before we actually change history? Bruno Latour recently directed us, actors in the throes of an epoch we want to call “the Anthropocene.”

Latour: “What to do? First of all, generate alternative descriptions.”3

I propose that we describe what places doinstead of what they are. Somewhere in these new descriptions will be anticipations of time when a new set of relations is possible or becoming. If the agony of our landscapes is a sense that they record things we don’t want, we must locate the record of things that we do want.

Or we risk dying trying. A noble death, of course.

But here are just two of many paths through how and now what.

POLLUTION

The Missisippians left us a record of shit. The most real source of discovery about the declination of Cahokia may come through fecal stanols that archaeologists are now investigating. Hard evidence may break years of soft speculation against an empiric horizon. So far, fecal evidence suggests that Cahokia population declined after flooding and possibly events not yet well understood, including climate change.4

An 1882 illustration of Monks Mound at Cahokia. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In February 2019, AJ White (a Ph.D. student in Anthropology at UC Berkeley) and others published an article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences releasing findings from a fecal stanol study of Horsehoe Lake, a large, natural lake within the Cahokia settlement area.5 The Mississippians at Cahokia defecated outdoors, and their excrement often ended up draining toward the lake. Decades of examining less venal aspects of Cahokia have not been as instructive as fecal research in suggesting how the first city there died completely.

White and the team found that the stanol density rose from 600 until 1100 CE but declined from 1200 until 1400. Five hundred years in, two hundred years out. St. Louis, by comparison, had 190 years in and is now either about 70 years out (city population) or 70 years flatlined (city and county population).

Eight hundred years from now, what stuff that we have dumped will show anyone that our city was declining?

We can look backward toward St. Louis’s Chouteau Pond, an occlusion of the Mill Creek made by a French miller, whose new pond became both the recreational grounds of a parkless city and a destination for shunted human waste. That the Euro-Americans, who also sent their shit to a body of water, could now judge the Mississippians or any other North American inhabitants as savage is deeply hypocritical, perhaps even pathological. (Today we send ours into a river into a gulf into an ocean. Is that what some Marxists call accelerationism?)

Thomas Easterly daguerreotype of Chouteau’s Pond, 1852. Source: Missouri History Museum Library and Collections Center.

The waste sent to Chouteau’s Pond ultimately killed at least 4,285 people through cholera in 1849. At that time, the city still lacked municipal sewage systems, although they soon would be built. The city’s response was to drain the pond, and the drained lowland soon was sold off to the newly-capitalized railroads needing lines through the city.

One hundred years later, and civilization in St. Louis progresses enough to match the last century’s shit with blood. When the city’s park commissioner unilaterally and hastily decided to integrate swimming pools to all humans in June 1949, the opening day of the pool at Fairground Park ended in the first and only race riot confined to the city limits of St. Louis. Anxiety over the future of north St. Louis spurred white people to attack not only black swimmers, but also white police officers who attempted to enforce the laws actually in place. Blood on the ground, blood on the hands of the white people who would abandon the pool and the park and an entire half of the city in short order. Did they take that blood with them?

The riot ended with official blame on both white and black people, a door closed on the pollution of racial violence for a generation. When we claim that East St. Louis or north St. Louis is precarious, do we mean that Ladue or Clayton or St. Charles is now too far gone, past precarity? Because I want to follow the blood from those hands, from those lunatic minds, not to badger the descendants of the people who just showed up to swim. Those who showed up to kill bother me more.

The American flag appears at the Boenker Hill Vineyard and Winery overlooking the West Lake Landfill. Photograph by the author, 2016.

The ultimate wormhole in St. Louis may be the possibly smoldering isotopes of the Manhattan Project waste tucked into the West Lake Landfill. We need a new concept of time to even think through what this waste could do to our settlement. Deep time. Not cheap time. Deep time forces us to think through a future of emergency declaration, forced evacuation, and harmful contamination that could outlive any current form of government existing here. If the waste’s worst fate means that our current mentality is inadequate, its best fate — removal and voluntary relocation — makes it someone else’s problem, in a different place and on a different time scale.

Middle class properties of the early twentieth century, on Holly Avenue in St. Louis. Photograph by the author, 2012.

Perhaps property is the worst form of pollution. Tracing the root of property back to Latin, to “one’s own,” we may find that the only real real property in the world is our blood or our shit.6 Yet, many people think it’s land that is owned, and we have bent land to accommodate a multiplication of parcels and houses. No one can exonerate any part of the region by picking on another, either, such as those who excoriate the suburbs or the gentrifying city neighborhoods for bourgeois excesses attempt to do. The code of private property arrived with French colonists, was perfected in the hands of urban elites, and ended up shaping New Town and Wildwood. We can call a part of the system exotic, but that’s like letting a snowflake land on your tongue and claiming it is the entire weather pattern.

A tract house rises in Monroe County, Illinois, near St. Louis. Photograph by the author, 2007.

St. Louis’s early twentieth century proliferation of capitalized land benefited in part from an import-export relation with the “Great Southwest”: Texas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. Finished goods and equity went out, while bauxite, lead, cotton, livestock, and petroleum headed northeast on St. Louis-controlled railroad lines for processing in that city. No finer memorial to this trade exists than the remaining chat piles that form a toxic heartland version of Monument Valley. Picher, Oklahoma, has become an uninhabitable Superfund site, with each headwind thick with tailings dust. The mines closed as their surplus value declined, and the St. Louis investors retreated without reparation. Much of the chat now forms road pavement, which breaks down. More dust.

Julius Huttawa, “Great Fire of the City on 17th and 18th of May 1849. View of the City of St. Louis.”

Why the River City never learned to revere dust eludes explanation. The entire central city was destroyed by dust in 1849, when the metonymic steamer White Cloud sent aloft a discharge of smoldering ash, a common urban atmospheric aspect of antebellum St. Louis. The discharge set the boat on fire, then flames leapt onto other steamboats, raw goods, roofs, and wagons. Dust to dust. The fire ended when volunteer firefighters used black gunpowder to detonate buildings along a firewall. One of the volunteers, Captain Thomas Targee, blew himself to kingdom come but ended the conflagration. The fire proved fortuitous and allowed for the capitalization of new cast-iron-faced modern warehouses along the city’s aged waterfront. Eventually those would be smashed to dust to build the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial at a time when bituminous coal dust banished the rising sun from the city for weeks.

Demolition begins in the Mill Creek Valley. Source: St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 1959.

Then the city would manically rush to make entire neighborhoods dust. Eventually, too, landlords seeking to offload worthless houses in north city during the white flight era would turn them into dust through fire, and that dust converted to cash through insurance settlements. Nowadays the fires continue, but they don’t produce exchange value. They just consume. Usually nothing replaces these buildings. The dust presumably settles somewhere, much of it in our organs, so that the artifacts of a long past speak through our ragged breath and altered vocal pitch, when dust exits us.

The James Clemens House in north city St. Louis, destroyed by fire in 2017. Photograph by the author, 2017.

No landscape element is anything but an arrow toward another, usually somewhere far away. No element is a solid mark except in the now. In the then and the later, it’s liquid, it’s transitory, it’s our own blood, the constitution of which links us to billions of people variously dead, alive, and not yet alive.

Landscape. Land. Shape. How. How. How.

KNOWLEDGE

Knowledge is power. Bacon, Hobbes, Foucault, you, me?

Political theorist Jodi Dean reminds us of the outcome of what we consider knowledge: “We can and already do make decisions about who gets what, who has what, what is rewarded, what is punished, what is amplified, what is thwarted.”7

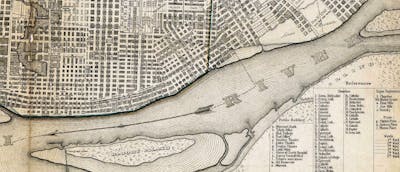

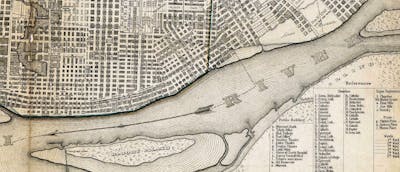

The expanded grid of the city taking hold, 1853. Source: Map of St. Louis, Wikimedia Commons.

No land has been shaped that has not been known, and rarely has any land been known that has not been shaped. Yet, landscape has always been produced in mutuality, in which the knower is shaped by the known. Sometimes the knower doesn’t want to know this. Sometimes encounter produces authority as a primary affect and ignorance as a secondary affect.

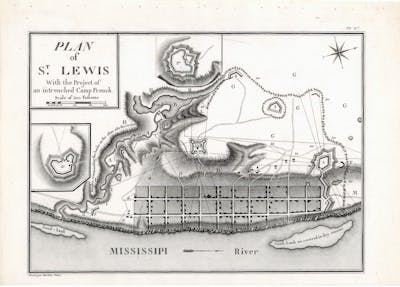

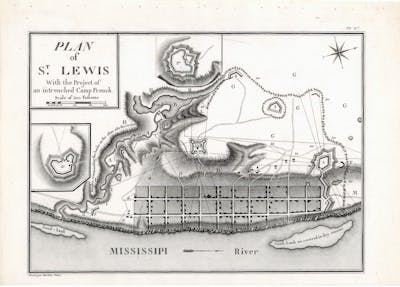

Collot plan of St. Louis, 1796. Source: Missouri History Museum Library and Collections Center.

St. Louis emanates from a great epistemic system in service to political power, the urban grid. The grid, subject to much urbanist adoration, instantiates power and joins land to human control. Our city’s base model is the Roman castrum with its ordinal fixity, the infinitely fungible web that could capture the entire planet’s surface. (In fact, under the pseudonym of the US Public Land Survey System, it tried.) It’s a dragnet of statecraft, a matrix of taxable land and governable subjects. The web is intrinsically a type of pollution, because it is a mechanism for making private property out of commons, which it did after the original village of St. Louis devoured common fields and conflicting, alternate spatial plans.

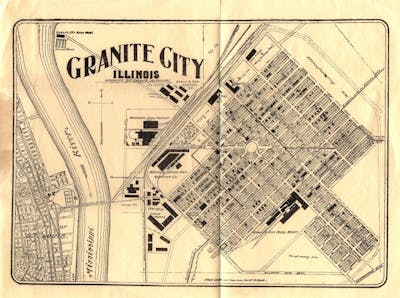

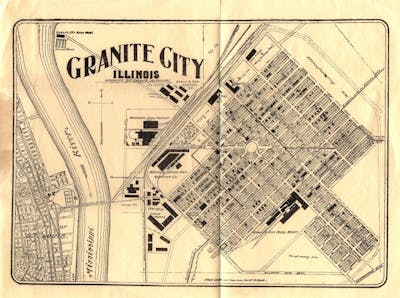

Map of Granite City from 1904 promotional brochure.

In Granite City, we sit on a grid with diagrid transects, a merger of Roman idealism and Haussmannian pomp. Does the flat plan of the city teach us anything? Certainly. Does it mislead us at the same time? Of course. Missing is what activist and critic Brian Holmes has termed “the cartography of togetherness,” a representation of sensory order.8 We have the lines of surveyors and tax collectors, endorsements of power, but not the aura of place, not the sense of place. No record that Granite City was a vicious sundown town from the moment the surveyors were hired to draw a line, no representation showing that, in 1990, only 69 out of 32,862 residents were black. Ten years later, in 2000, 622 out of 31,301 residents of Granite City were black. That was just 18 years ago. Outside of St. Louis. We’re left senseless by what.

Writer Eduardo Galeano posited that Europeans still do not know where they are in the Americas, that their colonization is a mask hiding a deep ignorance of where they are and with whom they share the continent. Perhaps the great university across the river in St. Louis knows something about where it is. With the best minds for miles around and $7.2 billion in endowment, this school has no rote excuse for not-knowing. In fact, it has spent millions — literally — to uncover the spatial politics of the “divided city.” So, when its retiring chancellor aims for a post-collegiate, civic commitment, he chooses to be the titular head and ombudsman for a city-county consolidation drafted in a closet and funded largely by a local oligarch. Knowledge of the landscape, knowledge of the divides, all seems to profit someone other than the inhabitants studied most often at school. Are the scholars just spectating the trauma of others, studying division but not healing divides? So far, “Better Together” has held four public meetings with 150 seats each. 600 of the 1.3 million people living across city and county have been allowed to read the chained manuscript, to receive communion into the chancellor’s cause. They don’t want us not to know what they don’t know. They must fear anything but the abstract truth. Maybe they fear themselves most. (Summoning the superego, please — the ego is making the map of the future again!)

Mayor Raymond Tucker and Sidney Mastre gaze at the Mill Creek Valley in St. Louis, 1956. Source: Missouri History Museum Library and Collections Center.

But it’s not what; it’s how, again. (And again.) The chancellor is not a temporally vacuum-packed agent of oppression. He follows centuries of the powerful not-knowing by knowing, the “dominator culture” that bell hooks has identified.9 The early French colonial settlers across the river from Washington University thought that the mounds of Cahokia had to be the achievements of a white people, or Toltecs, or maybe Hindus, but certainly not the “savage” indigenous Americans that they had encountered. Freud says we tend to aggress most severely against our immediate neighbors, right?

And so it went, until Cyrus Thomas published in the late 1880s a case that unknown — and, I submit, still unknowable — people had built the mounds.10 Mississippians. The mounds were no longer naturalized ruins, subject to projected pasts, but something with real incomplete material fact. The ignorance of the truth — the ontological heaviness of Cahokia as something to be known only a little more than now — has been too much for many white folks. They keep retreating to the safer ignorance of authority. They convince themselves that they know the place and they know who lived here, not through their shit, but through some cultural essence.

If anyone ever thinks that they know your cultural essence, run. They probably want your land or your life.

CONCLUSION

Now that we have the word “Anthropocene,” we may think that we know what time it is. We may think that we have living proof.

Or we may be facing a new millenarianism, where we whisper a word that we hope will absolve us, resolve our ways, reshape our world, and make the planetary moment something that fundamentally is about our capacity for reform.

Or we may be in denial.

Or we may realize that the lie of liberal democracy has finally overtaken its supposed truth, a long painful eclipse. Anthropocene is not commensurate with Anthropos unless every human had equal power to shape this time, equal wealth and equal culpability. Which Anthropos do we mean? We’ve avoided answering that question, hoping that we die, retire, hide behind a protected gate or get tenure before it gets answered, and meanwhile too often silencing those who have dared to ask.

Latour writes that humans aren’t up to the challenge of now because they think that the root cause and root passage through this era revolve around Anthropos instead of Planitis. We see the signs, detect the waves, and then see ourselves as central. We are great at aiming to know in order to end up not-knowing in profound ways.

Can it be another way? Does it matter?

Is it possible that, when we talk about the Anthropocene, when we read the landscape for evidence of catastrophic forces, we are looking fundamentally for a new politics? Politics will always be a human pursuit, and within politics we study landscapes like St. Louis and the American Bottom, and within politics we either let these places speak us or we choose to speak them in new ways.

Message from a dead retail storefront in north St. Louis County. Photograph by the author, 2016.

But speech is an act, acts come from power, and power is knowledge. To act differently, we must know differently.

Yet, politics without systems consciousness, without a dedicated understanding of the relationships that make the things, the how that we’ve managed to perpetuate as we study its affect — that may be no politics at all. Withdrawal — another human thing, tried and true.

Hiding out. Nightmare City at The Luminary in St. Louis, Missouri. Source: photograph by the author, 2016.

Apart. A part. A part of what?

Tourist always found, or human always lost but not alone?

Track your pollution, make a log of your knowing, and map the landscape that you make every day.

There is the Anthropocene. Right there, on the scale that you produce. And that you can undo.

Sign on Illinois Route 3 in Granite City, Illinois. Photograph by the author, 2019.

What on that map don’t you like, and how will you change that?

•

Review

By Sarah Kanouse

In March 2019, just as winter turned to spring, Michael Allen delivered this essay as a lecture-performance to about fifty people crowded into an unheated, ramshackle storefront in Granite City, Illinois. Perhaps half hailed from the St. Louis area, drawn by the opening reception for artist-curator Gavin Kroeber’s “Art + Landscape” exhibition, which sprawled across indoor and outdoor spaces in the scrappy, artist-led Granite City Art and Design District and included Allen’s performance. The other half, including me, hailed from a global elsewhere — a group of visiting scholars and artists affiliated with the Haus der Kulturen der Welt’s sprawling project, Mississippi: An Anthropocene River. Having spent much of the day thinking about the Anthropocene landscapes of St. Louis, we were a sympathetic audience, and everything about the performance just worked. The chipped linoleum floor, the uncomfortable chairs, the tabletop projector beaming snapshots, maps, and historical imagery at the wall, and above all Allen’s delivery — part beat poet, part tour guide, part wry commentator — were all inextricably part of the experience. You just had to be there.

I found myself longing for Allen’s performance while reading its script for Forty-Five. Animated by Allen’s voice, the opening invocation of names and events from the history of St. Louis drew visitors to the city into its palimpsests. It didn’t matter that some references engendered flashes of recognition and others not at all. Allen’s voice and gestures gave the litany a spellbinding quality, and what wasn’t legible became evocative. Similarly, the rhetorical questions and reversals that pepper the script registered during the live reading as active thought experiments. In print, it is more difficult to follow Allen on this deep time dérive of St. Louis. He gestures to possible arguments — most provocatively the deep time material entanglement of St. Louis’s biological inhabitants with various forms of dust, ash, and, in the case of the West Lake Landfill, potentially explosive wastes — but what the connections mean remains suggestively fuzzy. You just had to be there, in the same room, feeling it out together.

Presented on the page or screen, Allen’s words are stripped from the flow of time and no longer inhabited by a speaking/thinking/sensing subject. The reader’s reception of the text may be conditioned by expectations of precision and authority that thwart Allen’s intentions. Dear reader, please lay those expectations aside. At the same time, I wish Allen had employed some of the affordances of print, like additional footnotes, extended image captions, and even marginal annotations (perhaps as images) — to help modulate between one register and the other.

On a related note, Allen’s piece prominently uses the first-person plural pronoun, “we.” In the context of the original performance, the term “we” seemed locally referential: an assembly of audience and speaker linked by participation in contemporary art, a shared interest in the St. Louis landscape, and engagement with ideas of the Anthropocene. The print piece has a potentially more general public, a less specific “we” that risks standing in as a generic universal. Contrary to Latour’s claim, paraphrased by Allen, that “humans aren’t up to the challenge of now because they think that the root cause and root passage through this era revolve around the Anthropos instead of the Planitis,” there exist many thriving epistemologies that have never lost sight of the entanglement of the human in a more-than-human world. Moreover, as Rob Nixon notes, planetary environmental rhetorics can be valuable but risk a “universalizing, transcendental analysis in a way that sets up the problem as humanity’s problem without discriminating among the slow violence unleashed by different national and transnational actors.”11 In a piece deeply attuned to how racism, capitalism, and militarism co-produce urban space, clarifying who the “we” includes, excludes, and only partially encompasses would help show how, to paraphrase Nixon, “we” may all reside in an Anthropocene landscape, just not in the same way.12

Review

By Rachel Leibowitz

“The aim of meditating about the world is finally to change the world.”

Donald Barthelme13

“What? —RICHARD M. NIXON”

Thomas Pynchon14

15 April 2019

Is it true that all that is solid melts into air, and all that is holy is profaned? Is it?

Paris is burning. To be more specific, the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris is on fire. Now, as I write. Engulfed in flames.

As I sit here in my office in a historic building in a formerly-great Rust Belt city, a city that once was an industrial powerhouse built upon the shores of a lake sacred to the Onondaga Nation and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy that now doubles as a Superfund site…the spire of the cathedral has already succumbed to the blaze. It has fallen, perished. The roof is surely next. Then what?

In “How Not What,” Michael Allen instructs us to “describe what places do instead of what they are” and to make lists and maps of the ways in which we humans make imprints upon the land every day. Activities, actions; how, not what.

What?

One question keeps popping up in my mind, over and over: “What matters?”

Our buildings, our landscapes, our monuments, our everyday places — even the shit and the blood Allen mentions repeatedly…

What matters? What matters? What matters?

Like a mantra, that’s what thrums in my brain, the soft tissue and electrical impulses that help me to process it all, to get through it all. I do not know the answer. I never have. All these years working as a photographer, a preservationist, a historian, a public servant, an educator, the question has been plaguing me. What matters?

But mantras are for meditation, and this is not an act of meditation.

“How not what,” Allen charges. Or is it a helpful suggestion? He asks, “Can it be another way? Does it matter?”

Does what matter? Doesn’t “what” matter?

What matters? What matters? What matters.

Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

I sit here, horrified and temporarily paralyzed, and I am wondering what will replace the great cathedral. I have never been to Paris, I have never seen Notre-Dame, yet I feel such shock and sadness, as if I knew it intimately. It was announced a moment ago that a fundraiser to restore — or rebuild — the cathedral will begin tomorrow. Other news outlets are reporting that the focus so far has been on salvaging works of art and relics, and the 850-year-old building will not be saved. Crowds of people are surrounding the tragic site, watching the conflagration, sobbing and singing hymns.

Life is suffering. According to the Buddha, life is suffering, and attachment is suffering. Yet, the Buddha also taught that suffering is not without its causes, and those can change, and suffering can end.

Much of Allen’s essay focuses on what “we” (humans) know, what we don’t know or can’t know, how comfortable we are with not-knowing — what we steadfastly choose to ignore, to deny, to avoid. But these are intellectual processes, strategies for dealing with grief over the loss of places that are significant to us, the sadness and the anger felt when history and its associations within a place are denied or discounted for political obfuscation, private profit, or other reasons. Allen writes, “No land has been shaped that has not been known, and rarely has any land been known that has not been shaped. Yet, landscape has always been produced in mutuality, in which the knower is shaped by the known. Sometimes the knower doesn’t want to know this.”

Still, we know.

As Carl O. Sauer and other geographers, historians, and philosophers after him have said, humans shape the land, the land shapes us. The land has informed seafaring cultures, desert cultures, mountain and valley cultures, frozen cultures, agricultures — and those, in turn, further shaped the lands they occupied to suit their needs. That interdependence continues; it is ceaseless. Material shapes culture shapes material. What, how, what, how, what.

The land has long told us of its limits, things it cannot do, things it will not do. It is not in its best interests to accommodate us, our needs and our desires. Of course, the land does not know as we know, it does not care as we care; it has no morality, no ethics (but humans do). It is in a constant state of change, of motion. Big (dharma) wheel keep on turnin’. Pratītyasamutpāda—dependent arising:

When this is, that is.

From the arising of this comes the arising of that.

When this isn’t, that isn’t.

From the cessation of this comes the cessation of that.15

Interdependent existence. “Produced in mutuality,” Allen says. Just as Sauer and all the others said.

The complement to pratītyasamutpāda is sūnyatā, emptiness. Whatever arises dependently is empty of inherent existence. And because everything arises in dependence with other causes and conditions, all is empty of inherent existence. There is nothing that is not empty. Very reassuring.

In other words, what matters.

The vacant lots of St. Louis, Missouri, are empty, though they are not empty of matter or of what matters. In fact, they are full of matter, which means they are also full of energy — soils teeming with poisons and potentials we cannot see, flora and fauna of widely divergent shapes and sizes, history we may or may not know, and the fantasies of the children who play in such places or the plans politicians and developers have for them. Landscape architects and cultural landscape historians understand this. They recognize what matters within vacant lots. So often, too often, architects imagine vacant lots as voids, as if they were empty of causal existence and free of conditions—tabula rasa. But this is impossible. The open spaces, the sites of the former this or the future that, exist not independently, but only interdependently. From the arising of this comes the arising ofthat.

Matter is what makes them empty. What makes them empty.

What matters? What.

Notes

1

See Donna J. Haraway, “Staying with the Trouble: Anthropocene, Capitolocene, Cthlulucene,” Anthropocene or Capitolocene? Nature, History and the Crisis of Capitalism, ed. Jason W. More (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2016).

2

Claire Pentecost, “Notes on the Project Called Continental Drift,” in Compass Collaborators, Deep Routes: The Midwest in All Directions, eds. Rozalinda Borcilā, Bonnie Fortune, and Sarah Ross (White Wire, 2012), 18.

3

Bruno Latour, Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Régime (Medford, MA: Polity Press, 2018), 94.

4

Susan Alt, “Cahokia’s Boom and Bust in the Context of Climate Change,” American Antiquity (July 2009): 467.

5

A.J. White, Lora R. Stevens, Varenka Lorenzi, Samuel E. Munoz, Sissel Schroeder, Angelica Cao, and Taylor Bogdanovich, “Fecal Stanols Show Simultaneous Flooding and Seasonal Precipitation Change Correlate with Cahokia’s Population Decline,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112: 12 (March 19, 2019): 5461 – 5466.

6

For an argument supporting excrescence as the origin of real property, see Michel Serres, Malfeasence: Appropriation Through Pollution? (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011), 1 – 15.

7

Jodi Dean, The Communist Horizon (New York, NY: Verso, 2018), 118.

8

Brian Holmes, “Cartography with Your Feet: Workshop Proposal for “Beneath the University, the Commons”,” Deep Routes, 118.

9

bell hooks, The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, Change (New York, NY: Washington Square Press, 2004), 115.

10

Cyrus Thomas, “Work in Mound Exploration of the Bureau of Ethnology,” Bureau of Ethnology Bulletin 4 (1887): 1 – 15.

11

Ashley Dawson, “Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor: An Interview with Rob Nixon,” Social Text Online, August 31, 2011: https://socialtextjournal.org/slow_violence_and_the_environmentalism_of_the_poor_an_interview_with_rob_nixon/.

12

Rob Nixon, “The Anthropocene: The Promise and Pitfalls of an Epochal Idea,” Edge Effects, November 6, 2014: http://edgeeffects.net/anthropocene-promise-and-pitfalls/.

13

Donald Barthelme, “Not-Knowing,” in Kim Herzinger, ed., Not-Knowing: The Essays and Interviews of Donald Barthelme (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint, 1997), 24.

14

Thomas Pynchon, epigraph to chapter 4, “The Counterforce,” in Gravity’s Rainbow (New York, NY: Viking, 1973), 617.

15

Thānissaro Bikkhu, The Shape of Suffering: A Study of Dependent Co-arising (Valley Center, CA: Metta Forest Monastery, 2008), 16.

Biographies

Michael R. Allen works as an academic researcher, historian, teacher, design critic, public artist, critical spatial tour guide, and heritage conservationist in private practice. Currently, he is a Senior Lecturer in Architecture, Landscape Architecture and Urban Design, as well as a Lecturer in American Cultural Studies (AMCS), at Washington University in St. Louis, where he served as Coordinator of the AMCS Master of Arts degree from 2014 – 2018. Allen’s university teaching has focused on interdisciplinary investigation of architectural history, cultural landscapes, the economics of real estate and the politics of urban planning. Additionally, since 2009, Allen has been Director of the Preservation Research Office, a heritage consultancy, and is a federally qualified architectural historian who has worked on numerous preservation projects across the country. He contributed to the Mellon “Divided City”-funded Charting the American Bottom cultural landscape guide and, with Nora Wendl, managed the Pruitt Igoe Now ideas competition. The binding ties in his research are investigation of the ideological and political constitution of architectural and infrastructural space, a commitment to studying material heritage and its conservation, and advocacy for the forms of liberatory agency that realize the potential of the modern metropolis to distribute wealth, knowledge. and shelter. Allen’s essays have appeared in a wide range of scholarly and popular sources, such as Buildings and Landscapes, CityLab, Disegno, Next City, Temporary Art Review, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the St. Louis American, and Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes. Beginning in fall 2019, he will be pursuing a Ph.D. in Cultural Heritage at the University of Birmingham. Website: http://michael-allen.org Email: michael@michael-allen.org

Sarah Kanouse is an interdisciplinary artist and critical writer examining the politics of landscape and space. Migrating between video, photography, and performative forms, her research- based creative projects shift the visual dimension of the landscape to allow hidden stories of environmental and social transformation to emerge. Her creative work has been screened or exhibited at Documenta 13, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, the Cooper Union, the Clark Art Institute, the Smart Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, and in numerous academic institutions including CUNY Graduate Center, George Mason University, University of California Berkeley, and the University of Wisconsin. She has written about performative and site-based contemporary art practices in the journals Acme, Leonardo, Parallax, and Art Journal, as well the edited volumes Ecologies, Agents, Terrains (2018); Critical Landscapes: Art, Space, Politics (2015); Art Against the Law (2015); and Mapping Environmental Issues in the City (2011). A 2019 Rachel Carson Fellow at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Kanouse holds a permanent position in the Department of Art + Design at Northeastern University, where she directs the MFA program in Interdisciplinary Arts. She earned her MFA degree in Studio Art from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and a BA in Art, magna cum laude, from Yale University. Email: s.kanouse@northeastern.edu

Rachel Leibowitz is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF) and a co-director of its Center for Cultural Landscape Preservation. She has taught courses in the history of architecture and landscape architecture at the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Leibowitz’s past practice includes positions at two Chicago architecture firms, the Historic Preservation Division of the City of Chicago, and the state historic preservation offices of Texas and Illinois. Most recently, she served for five years as the Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer for Illinois and Division Head of the State Historic Preservation Office there. Leibowitz earned BFA and MFA degrees in photography from Washington University in St. Louis and Tulane University in New Orleans, respectively, and a Master of Architecture degree and a Ph.D. in Landscape Architecture (History and Theory) from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She is a board member of both the Alliance for Historic Landscape Preservation and the Preservation Association of Central New York and a past board member of the Vernacular Architecture Forum. Email: leibowitz@esf.edu