SPECULATION

Assuming a probability ß that a given investment will reach its maximum value, it then follows that there is a probability of 1‑ß that the investment will be worthless.1

Assuming a probability ß that a given investment will reach its maximum value, it then follows that there is a probability of 1‑ß that the investment will be worthless.1

Untitled II. Tres Piedras, New Mexico, 2013. Photo: Jesse Vogler

In the summer of 1962, Bill Irons — a 14-year-old boy from Erie, PA — and his parents turned their family car to the west. Wrapping their teal Cadillac around the Great Lakes, across the Great Plains, and over the Cascade Range, the Irons family brought their Cold War road-trip to a halt at the heart of the aerospace race: Boeing’s Seattle. Their destination: the Century 21 Exposition — otherwise known as the Seattle World’s Fair. Originally planned as a recapitulation of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909 and its celebration of an untamed American West, the pressures of a looming space race and the growing perception of a lagging disparity in science and technology led the organizers to focus on an optimistic, technologically-driven present instead of anachronistic themes of Westward landed expansion.

World's Fair sign at 47th & Aurora, 1962.

Item 70900, Engineering Department Photographic Negatives

(Record Series 2613-07), Seattle Municipal Archives.

Yet, there was at least one booth at the fair that did not get the memo. Robert Golubin, President of the Great Southwestern Land Company, set up a tent near the South entrance of the fair and, luring fair-goers with promises of free poodles and real estate, “auctioned” off ¼‑acre “resort ranchos” in Taos County, New Mexico. Shepherded in by a gregarious salesmen, Bill Irons and his family were steered toward the Space Needle and its adjacent land office to hear the spiel of a manic salesman eager to sell them a piece, albeit remote, of the American dream. Tres Piedras Estates, as the subdivision of ranchitos was named, were “generously endowed with the blessings of nature” and where, Golubin and his men assured them, “you will discover the gently rolling, fertile land that has caused the fabulous resort area in Taos county to become the playground of outdoor-loving people everywhere.“2

From Tres Piedras Estates. Undated brochure.

And everywhere was indeed their target market. Over 10,000 people from across the US, Canada, and beyond were the purported “winners” of Golubin’s land auction — receiving letters in the mail announcing their lucky draw with the only requirement being final payment of closing costs of roughly $50. Cheap for the promise of a sound property investment featuring “an abundance of colorful aspen, stately pine and fir trees,” as their brochures promised, but perhaps a shakedown for the ¼ acre of sagebrush and sand that actually awaited the buyer. With lots actually valued at approximately $3 and with over ten thousand people responding to their truly unbelievable “free-lot” luck, Golubin and his No-Shareholder-Liability company walked away with millions in fair-goers investments. Including those of Bill Irons and his family.

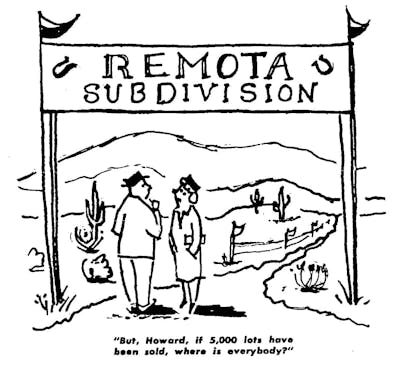

Set up in the shadow of Seattle’s Space Needle, Golubin recognized that speculation bears an uncomfortable kinship with the spectacular and the spectacle. Whereas the latter requires proximity, embodiment, and an immediate affective orientation, speculation relies on distance — a disembodied (and therefore not confirmable) vantage point. Unverifiability is the kernel to any successful land hustle. And as the sole mediator between the worlds of speculation and the spectacular, Golubin served as an unreliable narrator of promise and profit.

Rio Grande Estates advertisement from LIFE, March 9, 1962.

Tres Piedras Estates was only one of a series of speculative land scams that washed across mid-century America. Hawking pieces of primarily sunbelt real estate in New Mexico, Arizona, Florida, and beyond, various developers ranged in culpability from opportunistic truth-stretchers to flat-out thieves and liars. “Swamp Merchants” in Florida and costal states regularly sold lots covered by 3 feet of Everglades water, while the more audacious tried to build paper empires by selling deeds to land that simply did not exist. It was a speculative pattern where one expert decried, “This boom is filled with people trying to swing a $5 million deal on $5,000.”2 Golubin, for his part, actually owned the land which he was selling and had even made some of the internal improvements — such as grading the roads and staking individual lots — that he had promised to his clients. Yet, even those manifest efforts could not save Golubin from the courts, as he was tried and convicted of mail fraud under the Interstate Land Sales Act in 1965.3

Titlebar from U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Frauds and Misrepresentations Affecting the Elderly of the Special Committee on Aging. Interstate Mail Order Land Sales. 88th Congress, 2nd sess. Part 1. Washington, GPO, 1964.

L = Y(P‑C) – YDF

At the heart of this story are the dynamics of speculation. Eschewing traditional measures of fundamental value and focusing instead on the adaptability of price movements, the speculator enters into a pact with time, value, and uncertainty. But what land speculators of early- and mid-20th-century America relied on, in addition, was a structural misfit between distance and proximity that was a hallmark of the geographical imaginary of America. In a territory that exists beyond the prevailing models of land use economics — from Ricardo’s Law of Rent through von Thunen’s land equations, forward to the Chicago School’s sociological maps — understanding 20th-century land speculation requires an updated economic theory of the margin. That is, it requires a model in which distance and transportation costs factor as additive—rather than the conventional subtractive — variables. In the calculus of speculative advantage, the swamps of Florida and the desert of New Mexico were attractive precisely because of their isolation, remoteness, and inaccessibility.

Cartoon from Real Estate Subdivisions: How to Investigate Before you Invest. Undated brochure. Included in Interstate Mail Order Land Sales, 88th Congress, 2nd sess. Part 1. Washington, GPO, 1964.

Speculation, perhaps more than other abstract principles of freedom or democracy, sits at the heart of the American project. Looking up through the oculus of the dome of the US Capitol rotunda in Washington, D.C., a viewer is met by the pantheonic surface of a fresco detailing six abiding tropes of American self-narration: War, Science, Marine, Commerce, Mechanics, and Agriculture. The Apotheosis of Washington, a vast fresco with 15-foot high characters painted by Constantino Brumidi, is notable in our story for the presence of Robert Morris, “Financier of the Revolution.” As the central character of the tableau of Commerce, Morris, seated next to Mercury, the Roman god of commerce, is being handed a bag of gold by the winged god, who holds a caduceus in his other hand while Morris looks up in a tired glance from his ledgers. And while laborers toil at the turned back of Mercury, a merchant makes a deal, and a factory looms hazy in the distance, what is truly missing from this tableau of finance and capitol is the story of Morris as the country’s most notorious and, for a time, successful land speculator.

Detail from The Apotheosis of Washington. Constantino Brumidi, 1865. Photo: Architect of the Capitol.

In post-Revolutionary America, no land-jobber was better known or unmercifully caricatured than Robert Morris. “Bobby, the cofferer” occupies paradoxical positions in the historiography of American capitalists — appointed as Superintendent of Finances by Congress in 1781, he nonetheless maintained an active role in numerous speculative and dodgy land ventures throughout his tenure. Writing in 1780 to Silas Deane, his partner in the speculative United Illinois and Wabash Companies and the American Commissioner to France, he requested that he determine “whether it is practicable to make sale of vacant lands in America by sending out drafts or surveys, descriptions and certificates, to ascertain the situation, qualities of land, title, ect. [sic], and in what part of the continent lands are most desired by such persons as would be inclined to speculate, for I am ready to join you in any operations of this kind that would turn advantageously to ourselves […].“4

Speculative advantage operates in a surprisingly consistent way across time — be it of the Morris or the Golubin type. Reflecting on the pervasiveness of the speculative land scams of the 1960s, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy writes, “Advertising for such fraudulent sales has played on retirement hopes, the promise of the West, and the lure of easy credit,” continuing, “in the past two years we have experienced a sharp increase in the sale by mail of nearly worthless land for greatly inflated prices.”5 The first speculative mechanism that allows the “nearly worthless” patch of sage and sand to be sold for a profit is the practice of first-in-time land purchase and subsequent subdivision, whereby risk is spread across numerous smaller units far outside of a territory experiencing development pressures. Succinctly framing this calculus of risk, Robert Caro writes: “The reason is simple: The land is cheapest there, the chance for profit therefore the greatest.”6 The second mechanism lies in the recognizable metonym lying at the heart of Kennedy’s “promise of the West,” wherein uninhabitable desert is semantically transferred into “rancho estates.” And finally, the execution of any good speculative land scam is predicated on the mismatch of access to information and on the construction and capitalization of an unrealized desire — on “retirement hopes” or on the promise of owning a piece of the American Dream. All of which is to say, speculation relies, fundamentally, on trust. However misguided.

In the case of Golubin, this speculative chain was further reinforced by the pervasive geography of the postal system. As the medium through which the land sales of the Great Southwestern Land Company were announced and financed, mail delivery provided an anonymous but ubiquitous mechanism through which potential customers might be reached. Golubin and his associates would take part in land sales through the mail — sending information and notices of award of initial lots and soliciting further purchase through a $25 down and $25-a-month scheme. So, while their gambit had as its final object something as seemingly reliable and secure as land, it was the diffuse territoriality of the postal service that allowed this situated commodity to have purchase across the country. It was, after all, under the Mail Frauds Act that Golubin was ultimately tried and found guilty. Yet, while much has been written about the ways in which the postal system constructed connections across the vast territory of the country,7 there has been little comment about the ways in which the post simultaneously constructed distance. At the heart of most land-by-mail schemes is a structural interval introduced between buyer and seller. While the rhetoric of interconnectivity surely remains applicable in these speculative schemes, a second postal rule, the separation of sender and receiver, is the operative principle.

S30 T28N R10E. Aerial of the 1 mile x 1 mile subdivision of Tres Piedras Estates. Photo: Bing Maps.

Between the subdivided section of land called Tres Piedras Estates and practices of the Great Southwestern Land Co. lies the principle of property. The square mile in question is important because it crystalizes an abiding tendency in the American psyche that can only be described as a will toward speculation, one that reaches back to pre-Revolutionary real-estate practices, through early national land policy, through the guiles of 19th- and 20th-century land-jobbers, and forward to today’s housing crisis and the palsied response. But, more than just another emblem of this will to speculation, Tres Piedras Estates found itself at the heart of a mid-century real-estate crisis that included Senate hearings, postal reform, subdivision regulation, and an emerging set of rules for the management of land. The administrative suite of buying, selling, surveying, platting, and financing this square mile of land makes real a set of relationships that are often confused for property’s object. In this, we would do well to remind ourselves of the fundamentally relational definition of property:

In a strict legal sense, land is not ‘property’, but the subject of property. The term ‘property’, although in common parlance frequently applied to a tract of land or a chattel, in its legal signification ‘means only the rights of the owner in relation to it’. ‘It denotes a right over a determinate thing’. ‘Property is the right of any person to possess, use, enjoy, and dispose of a thing’.8

Yet, the success of a speculative endeavor, even barring specific fraudulent methods, is not a fait accompli—and, following economist Edward L. Glaeser, presuming that one believes the probability to be ß that a given investment will reach its maximum value as compared to investments of a similar category, it then follows that there is a probability of 1‑ß that the investment will be worthless. This 1‑ß probability is the risk that Golubin took on a sagebrush plateau in northern New Mexico.

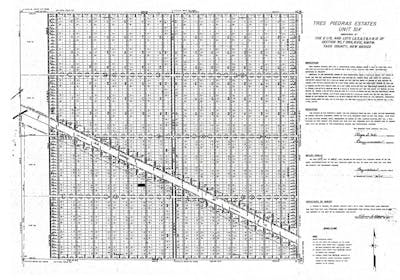

S30 T28N R10E

One square mile.

2223 lots. Roughly ¼ acre each.

A subdivision known as Tres Piedras Estates.

Tres Piedras Estates, Unit Six. Plat on file at the Taos County Commissioners Office.

Sited in the high-desert of northern New Mexico, the plat associated with the Tres Piedras Estates subdivision was a visionary document — if by visionary one means a seemingly irreconcilable gap between what-is and what-is-proposed. From a stretch of chamiza and sage-brush, the owners of the property, guided by a Mr. Thomas H. Wagner (NM Registered Land Surveyor #3517), conjured an urban gridiron plan of radical proportions. Only a little less quixotic than, say, the 1811 Commissioners Plan for Manhattan or the Public Land Survey System in which it is situated, Wagner’s plat subdivided the arid land atop a ¼‑mile thick lava flow into ¼‑acre house lots. Corners were staked with 2”x2”x5” oak hubs, and select roads were etched lightly into the sandy soils. This was one of three large-scale subdivisions initiated by the behest of Mr. Robert N. Golubin, president of the Great Southwestern Land Company, Inc., headquartered in Dallas, Texas, with offices at 636 San Mateo Boulevard S.E., Albuquerque.

Oak hub property corners, 2013. Photo: Jesse Vogler.

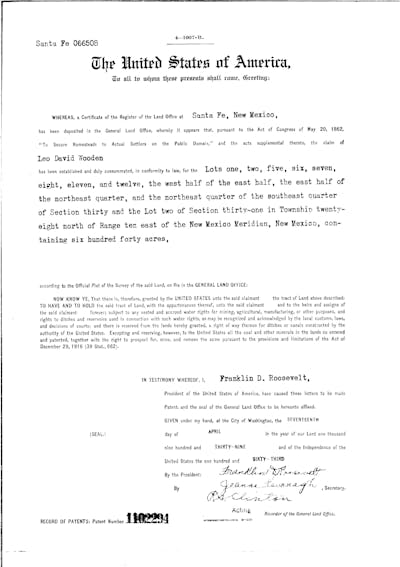

Section 30 is a tract of land claimed through the 1862 Homestead Act, albeit over 70 years later. In 1939, a certain Mr. Leo David Wooden submitted a Certificate of Register at the Land Office of Santa Fe, in accordance with the Act’s stated purpose “To Secure Homesteads to Actual Settlers on the Public Domain,” for nearly 3⁄4 of Section 30 of Township 28 North Range 10 East of the New Mexico Principal Meridian. The letter of this instrument was made patent under the hand of none other than Franklin Delano Roosevelt despite an egregious mathematical error in which the composite land described is called out as 640 acres on the Patent whereas the simple addition of the same tracts on the US GLO plat clearly only sum to 600 acres. Even the General Land Office, whose sole purpose was to organize the disbursement of the public domain, seems to have fallen trap to the common perception that land in this region was so uselessly interchangeable that easily verifiable imprecisions in original patents were accepted and entered in the cadastral register for all time. This 600 (née 640) acres was described by an earlier 1836 Petaca Land-Grant Plat as simply “Chamiza bushes” and classed in the 1918 US Surveyor General’s field notes as: “Soil, loam, rocky 3d rate.” A 1959 New Mexico Office of the State Engineer Report on Ground-Water Conditions fills out the geographic and geologic story as it characterizes this entire stretch of land as a lava-capped plateau with little or no sources of water to be found except through exceedingly deep wells.9

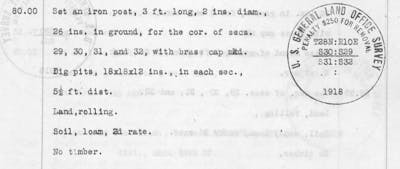

Detail from General Land Office Survey Field Notes, 1918.

While Mr. Wooden’s Actual Settler status10 is lost to history, he flipped his holdings only a short year later in an inscrutable transaction for the sum of “Certain Valuable Considerations and Ten and No/100 Dollars.” The grantees were a certain Sidney L. and Imogene C. Franklin — the former of whom was, according to the 1940 US Census, born in 1887. Sidney quickly consolidated his holdings and, on March 23, 1943, he filled out the holdings of section 30 by receiving the government patent to the final ¼‑¼ section. The Franklin’s holdings stretched across the high desert at an elevation of 7,850 feet, and the ranch house, yard, and corral they built there were some of the few human markers in the 30 miles of sagebrush between Tres Piedras and Taos.

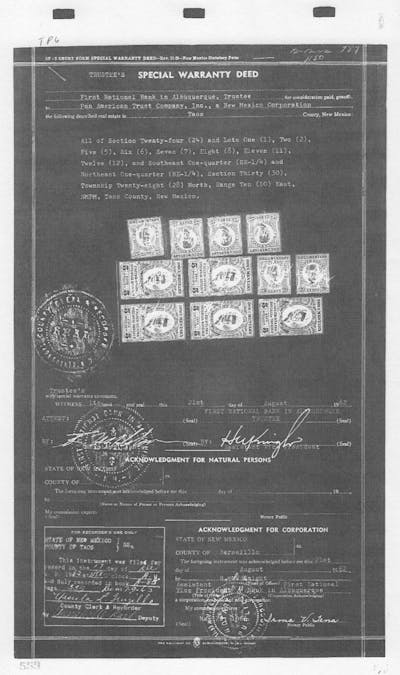

Special Warranty Deed transferring title to Pan American Trust Company, Inc., 1962. Deed on file at the Taos County Commissioners Office.

Franklin Ranch, as it would come to be known in the region, encompassed holdings of anywhere between 6 and 10 square miles, though their sage-brush kingdom was subject to the vagaries of arid landscape on the lava-capped plateau. The 1959 engineering report comments that the Franklin Ranch well, at some 473 feet deep, was completely dry and, owing to the unique geology of the area and the porosity of the native lava rock below the surface, known to be “blowing air.” Water, not air, was what was needed to grow a western ranching interest, which may be the reason why, in 1952, the Franklins entered into an irregular mortgage obligation with a Juan and Marian Iriart for the stocking and transport of cattle on their land. The text of this instrument, recorded in the Taos County Clerk’s Office, reveals the complex set of relationships and trade-offs that can sit at the heart of a property exchange:

The Iriarts agree to stock the lands covered by this mortgage, and it shall be their sole determination as to the number of head of cattle placed thereon. The Franklins shall receive one-third (1÷3) of the gain in cattle, and there shall be paid on the principal and interest of this mortgage, on the dates herein above mentioned, one-half (1÷2) of their one-third (1÷3). There shall be no monthly payments.

The Franklins shall have the care and custody of the cattle so placed on the said lands, and shall look after said cattle to insure that the said cattle are properly cared for at all times, and shall furnish salt, range and water for the said cattle.

The Franklins shall round up and deliver to shipping pens all cattle under their care and custody, at the times specified by the Iriarts. The Iriarts agree to furnish the necessary transportation to transport the said cattle to and from the properties.

That this arrangement was not in the Franklin’s best interest is attested to by the fact that, three years later, Sidney and Imogen granted to the Iriart’s the entirety of section 30 for the again mismatched sum of “One Dollar and other valuable considerations.” That this warranty deed exists in duplicate — one dated May 21, 1955, and the second Feb 23, 1957 — only further adds to the questionable nature of this transaction on land the rightful ownership of which would only become even more convoluted. Three years later, in 1960, the Iriarts liquidated their holdings in the area, and it was a short year later, on July 13, 1961, when the subdivision plat for Tres Piedras Estates was filed.

Enter Golubin.

At the time of the subdivision plat filing for Section 30, Township 28 North, Range 10 East, Golubin was not yet the legal owner of that property; and the transactions from the Iriarts to bank ownership to Golubin’s Great Southwestern Land Co., Inc., would be marked by mismanagement and retraction to such a degree that, to this day, title and ownership questions continue to plague all of the lots at Tres Piedras Estates. To explain the redundancies in title, we must introduce a third party: the Pan American Trust Company, Inc. — a No Shareholder Liability interest headed by Roger S. Cox, President. On the July 1961 plat that bears its name, the Pan American Trust Co. dedicates easements and rights of way for the newly imagined Tres Piedras Estates — easements and land that, in fact, they do not yet own. Indeed, not until August 1962 do the records show title being transferred from the bank to the Pan American Trust Co. However, in highly inconsistent chronology, the Pan American Trust Co. had already transferred ownership of the land in question to the Great Southwestern Land Co. in April of that same year, some four months prior to being granted actual title.

Original Land Patent, transferring title from US Government to Leo David Wooden, 1939. Patent on file at the Taos County Commissioners Office.

To add to these inconsistencies, the out-of-sequence title from Pan American to Great Southwestern included erroneous descriptions for the land being transferred, including approximately 65 acres of land not owned by said grantors. That latter fact alerted the Taos County Clerk to the inconsistencies in filing, and, at 9:50AM on March 1, 1963, in an instrument executed to correct the record “appearing in Book A‑76, Page 24, records of Taos County,” the Great Southwestern Land Co. quitclaimed the deed for the land in question to the Pan American Trust Co. At 9:52AM on that same day, the Pan American Trust Co. quitclaimed the corrected land description back to the Great Southwestern Land Co.

Which is to say, the Pan American Trust Company had legal, unencumbered ownership over said land for exactly two minutes.

In the two years that the Great Southwestern Land Company operated before Golubin’s 1963 federal indictment on multiple counts of fraud, it sold over 35,000 lots, making millions for the president of the company. Golubin’s first trial in New Mexico, in May 1964, resulted in a hung jury; however, a year later, in August 1965, the case was retried, and Golubin was found guilty of sixteen counts of mail fraud and was given three years on each count, with sentences to be served consecutively. With his case on appeal, Golubin relocated to San Jose, California, where he took up a job as a used car salesman. However, in March 1966, he was stopped for a routine traffic violation in his home state of California where separate warrants pertaining to land fraud in California came to light. As a distinct case, separate from the federal indictment in New Mexico, a California commissioner pressed charges and Golubin pled guilty to various Business and Professions Code violations — where he received suspended jail sentences and paid fines on each count.11 Two years later, in 1968, a federal judge revisiting the appealed mail fraud case from New Mexico upheld the district court’s decision, affirming the sixteen counts of fraud on the grounds that Gollubin’s scheme was “reasonably calculated to deceive persons of ordinary prudence and comprehension,” the threshold of prohibition in the mail fraud statues.12

Detail from Great Southwestern Land Co., Inc., letterhead. Collection of the author.

The number of original purchasers of lots at Tres Piedras Estates who actually made an effort to build and relocate to that patch of desert is not known. However, contemporaneous accounts in the Taos News suggest that, in 1963, the year in which charges were brought, hundreds of would-be homeowners made the trek to the Tres Piedras/Taos area to inspect their “free-lots.” According to these reports, most purchasers were happy with their lots. Indeed, on the ground, the primary complaint had less to do with the quality of land than on the County Clerk’s inability to register warranty deeds as fast as they were being issued. Yet, during the trial, US Attorney John Quinn told a different story when he quipped, “People might as well have won a ¼‑acre on the moon for all the good it did them.”

During a 1964 Congressional hearing in Washington, D.C., focused on interstate mail order land sales, Tres Piedras Estates was a recurrent point of reference. Yet, even proponents of regulation and punishment agreed that the burden of proof was heavy under the mail fraud statutes. Presiding Senator Harrison Williams, Jr., of New Jersey pointed to that condition when he noted, “All of the fingers of fraud must be shown and a lot of this is slippery misrepresentation, not hard and fast fraud.” Nevertheless, the courts disagreed a year later. The text of the 1965 ruling states,

[Golubin] dealt in deceitful statements of half truths and concealed material facts. His actions were not those of a legitimate business man engaged in the permissible “puffing” of his products. The ultimate issue is that of intent and it was resolved against the defendant by the district court which found that he acted with intent to defraud and that the scheme was “reasonably calculated to deceive persons of ordinary prudence and comprehension.“13

To this day, lots in the Tres Piedras Estates remain of dubious enough provenance that few real estate brokers will list them, and no banks will lend. Yet, that is precisely what draws many to the high desert in the first place. Now traded at public auction, a ¼‑acre lot can be had for as little as a few hundred dollars. Absentee owners are given a certain amount of time to respond to the county’s request for back-taxes, after which time their lots are put up for auction. And, while consolidation of lots remains a common practice for those already living there, recent years have seen spirited new residents once again clearing the ground and testing their architectural and social aspirations.

There is nothing which so generally strikes the imagination, and engages the affections of mankind, as the right of property; or that sole and despotic dominion which one man claims and exercises over the external things of the world, in total exclusion of the right of any other individual in the universe.14

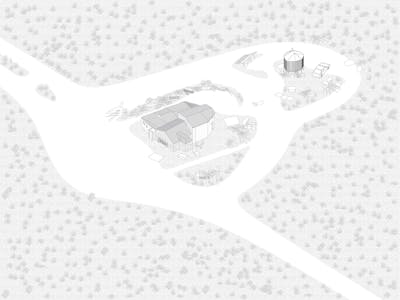

Untitled I. Tres Piedras, New Mexico, 2013. Photo: Jesse Vogler.

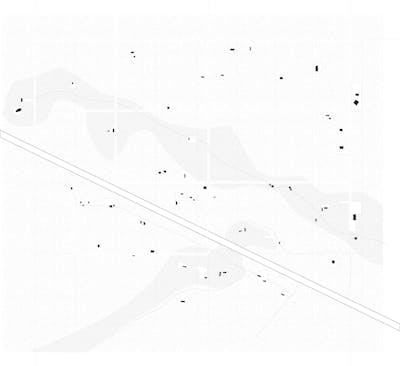

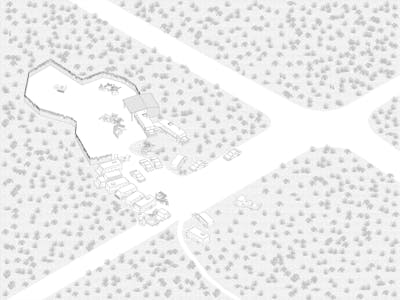

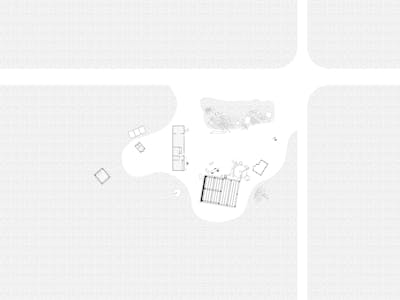

Of the nearly 2,300 lots in the square mile of Tres Piedras Estates, there are exactly 38 homesteads currently built. Of those, only a fraction are inhabited. From the air, the bones of the subdivision’s gridiron plan is still visible, but on the ground, roads lightly etched into the sagebrush and sand 60 years ago now dissolve into indistinguishable lines. All serve as reminders of the post-speculation vacuum that left this stretch of high desert with a rash of encumbrances blocking clear title to the land. This has not, however, stopped individuals from developing a specific and unique architectural language in their efforts to construct shelter and secure privacy.

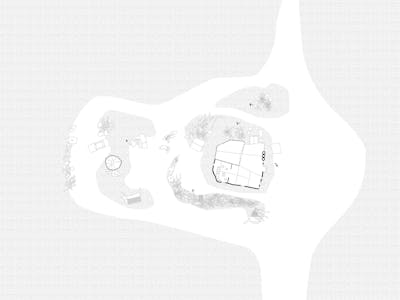

Tres Piedras Estates, Figure/Ground. Drawing by Jesse Vogler.

While it may be tempting to see these settlements as either part of the collectivist, countercultural projects of the 1960s or the militant, anti-government attitudes of the 1990s, neither is a neat fit. Instead, this tract and its inhabitants occupy a more ambivalent space akin to Bartleby the Scrivener’s “I would prefer not to.” These inhabitants have opted for a measured withdrawal, a calculated sidestep of either the pure communalist or virulent individualist models of alternative social order. Their way is marked, rather, by an opportunistic approach to boundary maintenance and building construction.

Each homestead is a loose agglomeration of buildings, outbuildings, abandoned cars, piles of scrap, and cleared sagebrush. Often incorporating the surplus of other building projects and demolitions from around the region, each “estate” carries with it an index of past elements. Painted siding, mis-matched timbers, patches of roofing — this is an architecture of the provisional over the planned. At work is a range of building technologies — from the timberframe to the dugout, from adobe bricks to tire infill. The pattern of homestead improvement follows those outlined by owner-built home advocates such as Ken Kern, the temporal staging of J.B. Jackson, and the architectural insights of Bernard Rudofsky, where the process of homesteading usually begins with the delivery of a mobile home, a modified school bus, or a trailer of some sort. That relatively fixed, contained, and weatherproof unit serves as the kernel for the homestead in process. Some inhabit those units for many years, while others continue their modifications and are quick to remove the imported dwellings in favor of slightly more permanent and spacious quarters.

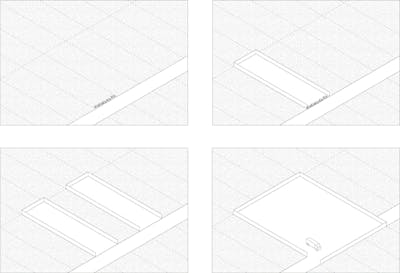

Sequential Lot Tactics. Drawing by Jesse Vogler.

Mirroring this provisional architecture is a surprisingly lax attitude toward boundaries, both legal and physical. Some homesteads begin with a sharply defined perimeter fence — constructed of anything from mud to recycled bottles to scraps of wood to the ubiquitous chain-link fence. Others, on the contrary, simply dissolve outward in a gradient of sagebrush and dirt, with the locus of inhabitation and extent marked simply by the patterns of use. These two models could not be more at odds with one another in terms of spatial definition, and each can be seen as an extreme response to the open field of the landscape. The boundary maintenance of the “fencers” recapitulates the lot-logic of the original subdivision plat, with the 63.8’x167.9’ lots often re-inscribed by a lone perimeter fence. Those of the “dissolvers” adopt the logic of the sagebrush — prioritizing continuity over enclosure. But what both recognize is that, as a landscape type, the fence carries with it a broad set of associations — from enclosure and boundary maintenance to clarity and neighborliness. It is as often the site of exchange and sociality as it is the site of confrontation and conflict. And as residents of gated communities, ranchers, and border-wall advocates all know, the fence is a fundamentally political architecture.

The Hideout

The Hideout takes a jaunty approach to boundary definition. Composed of fragments of found fences and an array of jalopies, the Hideout marks a clear, aggregated figure in the sagebrush landscape. Its fence arcs and expands as each new fragment is inserted within the expanding frontier logic of the enclosure. Drawings by Jesse Vogler and Yi-Jung Lo.

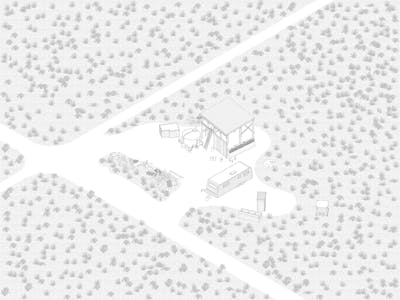

The Caretaker

With its two-story frame outpost, the Caretaker watches over the horizon of Tres Piedras. Tenuously held together by the accoutrements of self-sufficient living — pit toilet, water tank, compost heap, sauna, trailer, and scrap piles — the Caretaker hosts a solitary dweller as its loose collection of outbuildings disaggregate across the desert floor. Drawings by Jesse Vogler and Yi-Jung Lo.

The Earthship

As the most well-established “estate” in the Tres Piedras subdivision, the Earthship is a playful meeting of well-known counterculture building technologies and a sort of farm-yard know-how. Borrowing the earth-filled tire technique from the more well-defined Earthship typology just down the road, this instance eschews ideological and formal purity in favor of the phased contingency of life that marks this contested stretch of desert. Drawings by Jesse Vogler and Yi-Jung Lo.

More than just a recapitulation of the lot logic, however, the perimeter fence regularly becomes a spatial agent as it is mobilized to disregard checkerboard ownership and to span across and incorporate the public right-of-way in a piratical effort to enclose ever more space. As the diagram above illustrates, a fence can be used in the not-so-subtle incorporation of an un-owned tract into the body of a homestead. Taking advantage of both the paradoxical visibility and distance of the Tres Piedras Estates, it is common practice for adjacent land-owners to claim ownership over properties that are not legally theirs through a liberal reading of the law of Adverse Possession — what are commonly referred to as squatter’s rights. Here, the politics of the visible prove crucial. The fence makes explicit the occupier’s intent of adverse possession by 1. Declaring actual possession of the property, 2. Claiming open and notorious use of the property, 3. Establishing a claim for the continuous use of the property, and 4. Distinctly stating the exclusive use of the property. These are four of the five conditions laid out in US law, with each state designating the duration required for someone to claim title through adverse possession. In New Mexico, that duration is 8 – 10 years.

What these fences make explicit, then, is that property, rather than being an unambiguous object of fixed titular reference, is a subject of regular revision and construction — constituted and re-constituted in the steady process of transfer. Which is to say, following Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld, one of the most important writers on an updated theory of property rights at the turn of the 20th century, that property is not a thing, but a relation. Rather than a simple and non-social relationship between a person and a thing, it is a set of legal relations between people — what has come to be known as the “bundle” of rights, powers, privileges, and immunities.15 And, while this de-coupling of thing and its ownership has been posited as a theoretical model, the land that has come to be known as Tres Piedras Estates has been consistently revised, incorporated, and alienated throughout its 100-year history of mis-registered ownership in an ongoing project testing the objective status of belief.

At the heart of this belief structure lies the question of property and the material and discursive encumbrances that stand in and perpetuate its status as real, indelible, and immanent — in short, at the heart of this structure of belief lies the survey. Within the catalog of spatial practices, the survey carries the incomparable burden of being at once the most specific as well as the most abstract document pertaining to land. The survey and the surveyor quietly mediate, and thereby shuttle meaning across, some of the more enduring intervals in western thought — between the concrete and the abstract, the self and the state, the personal and the political, and affect and administration.

As I use it here, the survey is distinct from the map in one primary way: it foregrounds the idea of property, of ownership, and of use. It is, as such, not a synthetic, panoptic whole but, rather, an intimate register of accumulated subjectivities. Whereas the map can discard certain cultural residues in favor of natural totalities, the survey clings tightly to the human space of inhabitation and value. Recorded in so many county registers and accumulating in assessors’ archives, surveys participate in two key components of state power: reproducibility and verifiability. With its roots in taxation, allotment, and description, the survey is by its very nature a political instrument. Politics is integral to the work of the surveyor, whose charge is ultimately that of the state. The registry of property, the cadastre, is at once a fragment of the census project and an instrument of territorial accounting. It is no accident that, in the past, to be was to be counted, which meant to be propertied. Until relatively recent times, then, the survey served to verify one’s subjectivity and subject-hood, and, ultimately, discursive addressability (as, for example, a constituent unit within the expanding postal matrix of the state).

In the US, the inviolability of the private property system, unremarkable and nearly invisible in the landscape, constitutes the fundamental, foundational orientation and texture of the built environment in a way that belies its own silence. Boundaries, fences, property, speculation — these are all constituent parts in Max Weber’s “monstrous cosmos” of the contemporary capitalist economic order. Property relations overdetermine modes of sociability as well as outline a limit to individual action and affect. Yet, within the design disciplines, such relationships are rarely, if ever, considered. This reflection on fences, surveying, boundary maintenance, and speculative architecture, as exemplified at Tres Piedras Estates, seeks to redress that shortcoming by linking the material specificities of property — its histories, descriptions, and limitations — to its abstract generalities — geometry, law, and bureaucracy.

The author would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Graham Foundation and the brilliant founders of PLAND, an artist’s residency where the foregoing research was undertaken.

By Catrin Gersdorf

As a European traveling through the United States, the vernacular architecture of makeshift homes and settlements that is thinly scattered across the wide planes and open deserts of the Southwest has always been a cause of wonder and disbelief. Do people really live here, in the middle of this dry nowhere? What has tempted them to settle forty, fifty, sixty miles away from the next town that provides the basic infrastructure of food and gas? Not to speak of such modern amenities as medical services and education? How do the people who live in these few and far-apart homes make a living? And what do they do all day long if they don’t work for a living? Jesse Vogler does not answer any of these questions. But then again, he didn’t ask them either. Instead, he draws attention to the pathos of land speculation that emerges from a story in which the soil, and what can be found in it or what grows on it, no longer matters. The speculator sells a dream, an image. At its core is the idea that property provides freedom and existential security. Thus property becomes the ontological hallmark of modern subjectivity. I possess, therefore I am. More than three hundred years ago, at the dawn of capitalism, labor was necessary for converting the earth’s commons into private property, at least in John Locke’s theory. For Locke, the labor of a man’s body and “the work of his hands” mix the “property in his own person” with the materials that are in “the state that nature hath provided.” Consequently, “as much land as a man tills, plants, improves, cultivates, and can use the product of, so much is his property.”15 But in practice, fences became much more effective signatures of property than labor. And in the history of settler colonialism in America, speculation preceded cultivation. The speculator’s grid, and the property relations it prescribes, Vogler suggests, “outline a limit to individual action and affect.” This may be true. But his example, Tres Piedras Estates in the New Mexico desert, reveals something else: those who choose to make a dwelling out of the speculator’s lot tend to push the limits set by history, the law, bureaucracy, and geometry. I still don’t know what people do and how they spend their time in the deserts of the American West. But I now know how to read the architectural bricolage they call their homes, and the places they make for themselves in landscapes that belie the speculator’s cunning fictions of lusciousness and beauty — as spaces produced by the joined forces of American mythology, psychology, and the speculative economy of capitalism.

Adapted from Edward L. Glaeser. “A Nation of Gamblers: Real Estate Speculation and American History.” Transcript of Ely Lecture, Harvard University. 2013.

U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Frauds and Misrepresentations Affecting the Elderly of the Special Committee on Aging. Interstate Mail Order Land Sales. 88th Congress, 2nd sess. Part 1. Washington, DC: GPO, 1964. P. 102.

Robert N. Golubin, Appellant, v. United States of America, Appellee, 393 F.2d 590 (10th Cir. 1968).

From A. M. Sakolski. The Great American Land Bubble. New York, NY: Harper and Brothers, 1932.

Robert A. Caro. “3 Indicted in Top Mail-Land Gyp.” Newsday. March 15, 1963.

Robert A. Caro in U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Frauds and Misrepresentations Affecting the Elderly of the Special Committee on Aging. Interstate Mail Order Land Sales. 88th Congress, 2nd sess. Part 1. Washington, DC: GPO, 1964. P. 92.

See, for example, W. E. Fuller. The American Mail. Chicago, IL: U of Chicago Press, 1980.

J. Selden, in Wynehamer v. People, 13 N. Y., 378, p. 433, cited in Justice Jeremiah Smith, Eaton v. B.C. & M.R.R. Co., 51 N. H., 504, 511.

I. J. Winograd. Technical Report No. 12: Ground-water Conditions and Geology of Sunshine Valley and Western Taos County, New Mexico. Santa Fe, N. M.: State of New Mexico, State Engineer Office; prepared in cooperation with the United States Geological Survey, 1959.

In an anticipatory effort to forestall speculative land ventures of the very type that would come to define the land in question, typical US Land Patents make explicit the governmen’t intent “To Secure Homesteads to Actual Settlers on the Public Domain.” Actual Settler status was meant to encourage the actual settlement of the public lands of the U.S., rather than in the accumulation of title for speculative purposes. Actual Settler status was confirmed through evidence of labor and improvements — from tilling soil to planting trees to running fences to constructing a house — but with Mr. Wooden only having title to his land for one year, it is now not possible to determine if he truly intended to settle the land in question.

Gusow v. United States, 10 Cir., 347 F.2d 755, 756, cert. denied 382 U.S. 906, 86 S.Ct. 243, 15 L.Ed.2d 159.

Quoted in Robert N. Golubin, Appellant, v. United States of America, Appellee, 393 F.2d 590 (10th Cir. 1968).

William Blackstone. Commentaries on the Laws of England. Vol. 2: On the Rights of Things. Ch. 1: “Of Property in General.”

Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld. “Some Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied to Judicial Reasoning.” In The Yale Law Journal. 23:1 (1913).

John Locke. Two Treatises of Government (1690). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003. Book II: Second Treatise. Chapter V: “Of Property.”

Jesse Vogler is an artist and designer whose work sits at the intersection of spatial practices, material culture, and political economy. Drawn to questions that attach themselves to the periphery of architectural production, his projects take on themes of work, law, property, expertise, and perfectibility. Recent projects include a series of exhibits on the administrative landscape with The Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI), a performative project on commoning with the Center of Contemporary Art Tbilisi, a set of site-specific installations at PLAND, and a collaborative, multi-platform project of critical geography centered on the American Bottom. Vogler’s work has been supported by awards from the Graham Foundation, Mellon Foundation, MacDowell Colony, and the Fulbright Scholar Program and has been exhibited at the Venice Architecture Biennale, the CLUI, the Center for Contemporary Arts Santa Fe, and the Urban Institute for Contemporary Arts. Recent publications featuring his writings and work include [bracket], MONU, Ground Up, Artforum, Domus, and the Los Angeles Times. In addition to his art practice, Vogler is a land surveyor, co-directs the Institute of Marking and Measuring, and is an assistant professor of landscape architecture in the Sam Fox School, Washington University in St. Louis. Email: jessevogler@gmail.com

Catrin Gersdorf is Professor and Chair of American Studies at the University of Würzburg, Germany. She completed both an undergraduate degree and a Ph.D. (Literary Studies/American Studies) at Karl Marx University in Leipzig. Between 1991 and 2012, Gersdorf taught at the Freie Universität Berlin; the Universities of Hannover, Kiel, and Leipzig; Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich; and the Warsaw School of Social Sciences and Humanities. She has also been a visiting scholar at the Critical Theory Institute of the University of California, Irvine, and the Southwest Institute for Research on Women at the University of Arizona, Tucson. Gersdorf is the author of The Poetics and Politics of the Desert: Landscape and the Construction of America (2009) and co-editor of six volumes, including Natur, Kultur, Text: Beiträge zu Ökologie und Literaturwissenschaft (2005), Nature in Literary and Cultural Studies: Transatlantic Conversations on Ecocriticism (2006), The Cultural Career of Coolness: Discourses and Practices of Affect Control in European Antiquity, the United States, and Japan (2013), and America After Nature: Democracy, Culture, Environment (2016). Her essays have appeared in numerous edited volumes — for example, Ceremonies and Spectacles: Performing American Culture (2000), Transcultural Spaces: Challenges of Urbanity, Ecology, and the Environment (2010), Ecology and Life Writing (2013), and Cosmopolitanism in the Age of Thomas Jefferson (2013) — and in distinguished journals, such as Amerikastudien/American Studies, Anglia, Bucknell Review, Journal of American Culture, and Ecozon@: European Journal of Literature, Culture and Environment. Email: catrin.gersdorf@uni-wuerzburg.de