The official founding of the Street Observation Society, June 10, 1986.

Now, whatever you might think,

The gods dwell in the streets.

To put that in slightly more concrete terms, there has been a shift in the orientation of the banner of our era:

On paper → On the streets

Appreciation → Observation

Art for adults → Science for children

Spaces → Objects

I want to explain in detail why we have ended up in such a state.

First, let’s take the exemplary case of Wajiro Kon.1

Since childhood, he was an artist. With a small body and a face like a little monkey, he was a dunce when it came to studying and just liked drawing pictures. As a primary school student, he spent his time alone sketching each building along Teramachi Street in his hometown, Hirosaki.

A child with these tendencies must inevitably grow up, and it seems likely he would become involved in observation. In his case, he got mixed up in the folklore studies of Kunio Yanagita.2 During Taisho years 6 – 11 (1917 – 22), he tagged along on Yanagita’s tours of farm villages and learned methods of collection and observation while sketching the thatched roofs of the minka (vernacular houses). However, during those five or six years, for some reason, he slumped into an “utterly nihilistic feeling” with regard to Yanagita’s folklore studies.

As if awaiting the right moment, in Taisho year 12 (1923), Tokyo was entirely destroyed.3 On the scorched earth, he began to do two things.

One was the task of using whatever came to hand to decorate the “barrack” buildings that were being hastily built to provide shelter. He asked his art-school colleagues to form a “Barrack Decoration Company,” for which they distributed handbills in the street to solicit clients and then, whenever asked, they would rush with ladders over their shoulders and paint cans in their hands to apply “barbarian decoration as Dadaist art.”

His other task was to observe the practical aspects of the lives of people forced to begin again in the fire-devastated areas. From the signs drawn on pieces of scrap wood to the kinds of clothes worn by people passing through the town, he made sketches of whatever he saw. This is the origin of today’s modernology. If today’s authentic modernology — for example, Genpei Akasegawa’s Thomasson Observation Center and his search for Thomassons; Shinbo Minami’s flyer observations; the search for Western-style buildings by the Tokyo Architectural Detective Agency formed by Terunobu Fujimori, Takeyoshi Hori, and others; Joji Hayashi’s manhole collection; Nobuyuki Mori’s observations of schoolgirl uniforms; and Tsutomu Ichiki’s fragment collection4—is traced back to its origins, we arrive at Wajiro Kon.

So, I guess you could say that modernology was established as a result of Wajiro Kon’s sudden turn away from the paths between rice fields toward the metropolitan streets. He himself quit the practice of modernology once the reconstruction of Tokyo was complete, but the term modernology headed out on its own and grew up to be a common word in present-day journalism.

However, I feel it might have grown up a little too much.

In comparison with its mind, only its body has developed into a word for seducing men, or worse, for seducing magazines. For example, the expression “___ modernology” is appended to restaurant reviews, the quality of love hotels is discussed under the title “Faddish Modernology,”5 and today the word modernology is, to phrase it nostalgically, “the cul-mi-nation of me-dia mani-pu-lation in the sales strat-egies of the con-sumer economy un-der the ad-vanced develop-ment of the glo-bal capi-talist sys-tem” — which seems to be true, but put more simply, modernology nowadays has become sullied by the fingerprints of too many people from the world of commerce.

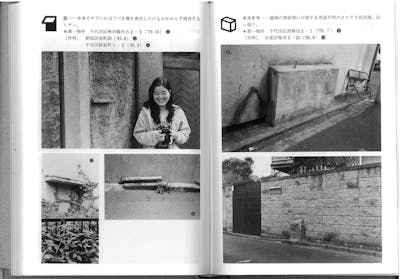

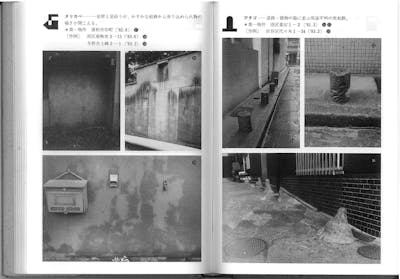

Street observation equipment. From Rojō kansatsugaku nyūmon [Street Observation Studies Primer] eds. Genpei Akasegawa, Terunobu Fujimori, and Shinbo Minami (Tokyo: Chikuma Shōbō, 1986).

Rather than young Yasuo Tanaka, we should recall the dignified figure of the original modernology, begun by Wajiro Kon and Kenkichi Yoshida.6 They did not observe the merchandise displayed in storefronts, but instead observed the signs painted on scrap lumber next to that merchandise. Furthermore, utterly unconcerned with what kinds of signboards were better for business, they directly collected what they found to be interesting in the signboards as things. This attitude of going direct to the things is important, as it prevents the intrusion of lust or hunger.

So, unlike young Yasuo, you cannot just enter a shop and pick up the merchandise, and it’s no good to stay sitting at a table. The team of Kon and Yoshida was always and only on the streets, for the streets.

Consumption is BAD, observation is GOOD. In a shop is BAD, on a street is EXTRA GOOD.

This is the true heart of modernology. So, for those of us who have discovered the gaze of Kon and Yoshida within our own eyeballs, we say a brief farewell to the modernology that has sullied by so many fingerprints, and proclaim that we want to use these words:

ROJO KANSATSU (street observation)

The “sense of passing through” in rojo (on the street) seems witty, and the “scientism” in kansatsu (observation) seems cool. I think Kon would approve.

*

Well then, to combine rojo with kansatsu is obviously to launch an attack on the domain of anti-rojo and anti-kansatsu. While this is an exaggerated statement, the gap between that domain and ours may appear narrow, but I feel it’s a very deep gulf.

The hypothetical enemy confronting us street observers is nothing other than the empire of consumption, with which we have already bumped scabbards7 thousands of times. For a long period this empire’s territory was limited to shop interiors. They maintained a friendly relationship with our kingdom of the streets as long as we each kept within the boundaries, but, recently, they have revealed territorial ambitions toward the inherited streets upon which we live, and they are steadily stocking up on weapons for an invasion — at least, that’s the information we received. For example, the old guy in D shop on H street in Tokyo declares, “If I don’t go out on the streets, I’ll go out of business,” suggesting a strategy of commercialization across the whole city, and in one area a strategy of fording the river has already succeeded.

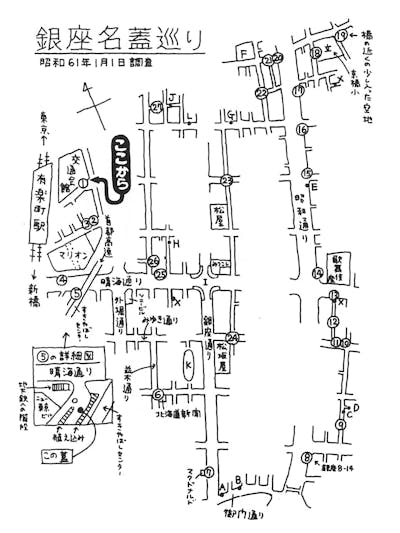

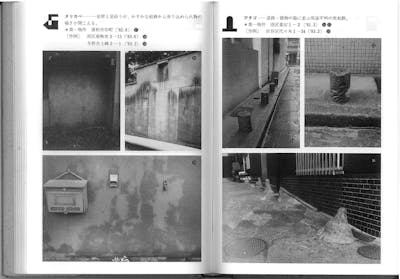

Street observation map, Ginza district. From Rojō kansatsugaku nyūmon [Street Observation Studies Primer] eds. Genpei Akasegawa, Terunobu Fujimori, and Shinbo Minami (Tokyo: Chikuma Shōbō, 1986).

Given this crisis, we need to be cautious about the way that the empire of consumption has suspended their formerly blatant battle tactics, which used the principles of big battleships armed with commercial weapons of mass production and mass consumption, and is instead frantically trying to develop new weapons that somehow convey a feeling of the personal gaze and the freedom to drift.

So, perhaps “street sensitivity” must be a major component of the gunpowder packed into these new weapons. However, a truly pure street sensitivity can recall the profound pathos of the city in a weather-beaten cast-metal manhole lid, see Sada Abe8 in the stump of a roadside telephone pole, feel the sweet innocence of human society in flyers stuck on a wall, imagine the entire world in the melancholy chickweed that sprouts inside a disused, rusty hand-pump — it’s those kinds of sensations. Such trivial things can’t be used as weapons of consumption. If you think they can, then give it your best shot!!

Having said that so confidently, it’s painful to see that much of the urban theory boom of recent years is somehow complicit with the empire of consumption’s strategy of invading the streets. Looking at newspaper advertisements by publishers of books with the word “city” in their titles, the standard three-line blurb on the left-hand side of the page will contain phrases like “urban festivity” or “stimulating the sensitivities and desires of modern people…with the town as a stage for the protagonists of a drama…hunters chasing information and symbols…analyzing the codes of the rich mirror of the city…discussing the full range of the charm of the spaces,” but this “festivity” and “charm of the spaces” has an unexpectedly dubious character. The words point in the right direction, but are always double-edged swords, which finally, in fact, benefit the empire of consumption in more than a few cases. Until now, not a single one of these concepts has avoided being consumed by that empire, so street observation also must be vigilant.

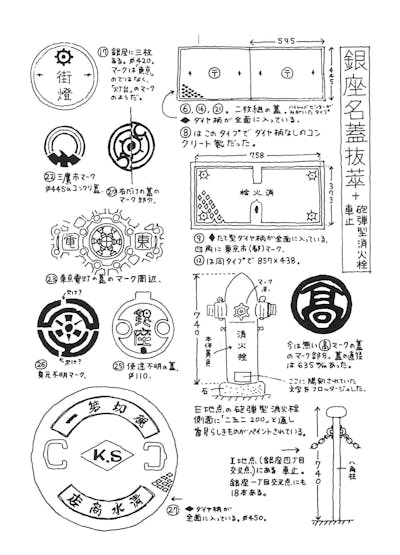

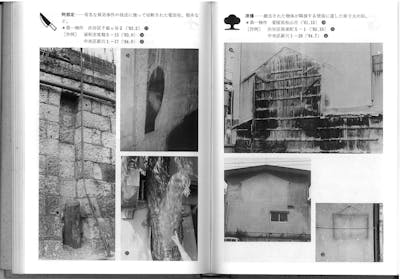

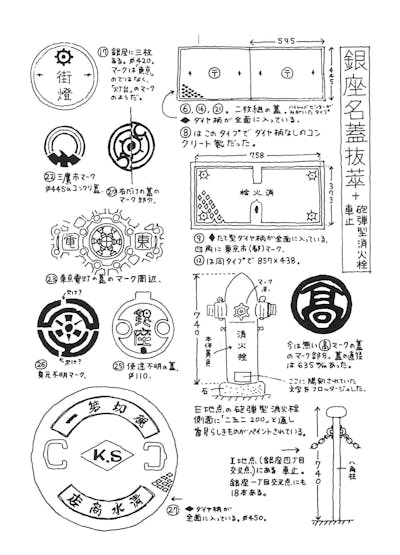

Manhole covers, hydrants, and other objects observed in the Ginza district. From Rojō kansatsugaku nyūmon [Street Observation Studies Primer] eds. Genpei Akasegawa, Terunobu Fujimori, and Shinbo Minami (Tokyo: Chikuma Shōbō, 1986).

Well, accepting these territorial problems between the empire of consumption and the kingdom of the streets, let’s move on to a discussion of the next hypothetical enemy.

Its name is art. Well, it isn’t quite correct to call that an enemy nation. Rather than being opposed to street observation, in historical terms, art is precisely one of the nostalgic “hometowns” of street observation. Both Kon and Yoshida came from an artistic village. But even now there is a touch of obsessiveness with regard to this maternal hometown of street observation, due to a dark past: back in the old days, when street observation was still a young schoolboy in the art village, it was bullied, so it deserted the village and lit out for the capital city. Then again, thinking about it now, the bullying was, naturally, unavoidable due to the little brat’s bad habit of yelling radical things like “Demolish the art village!” then plunging into the sacred grove of the village shrine with its shoes on and kicking away the treasured “beauty” that had been passed down to the village from great antiquity. The chief brat, Genpei Akasegawa,9 confesses the surrounding circumstances in the opening pages of this book, but the stages that followed the rural exodus from the art villages that began in the 1960s may be explained as follows:

The stage of art in museums … an era of sculptural self-expression in the city, such as the “Independents” exhibition.10

The stage of art on the streets … an era of physical self-expression on the street, such as the Hi Red Center.11

The stage of street observation … an era of extinguished self-expression, such as Thomassons.12

After this hop-step-and-jump, the “personal expression” that can be described as a tacit premise of modern art was obviously extinguished by the signature of R. Mutt,13 so perhaps we could also call this the longest jump that has succeeded in going farther than Duchamp. It’d be a great story, but, actually, doesn’t it just revert to kids playing in the streets?!

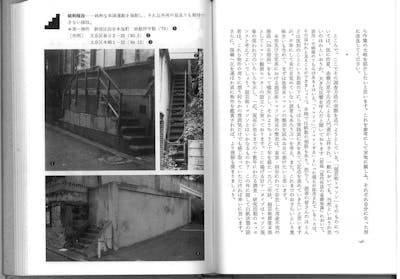

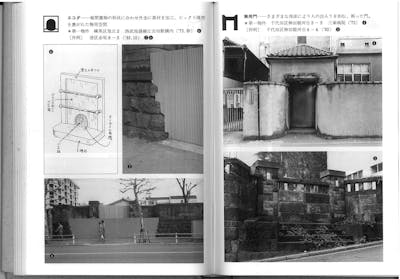

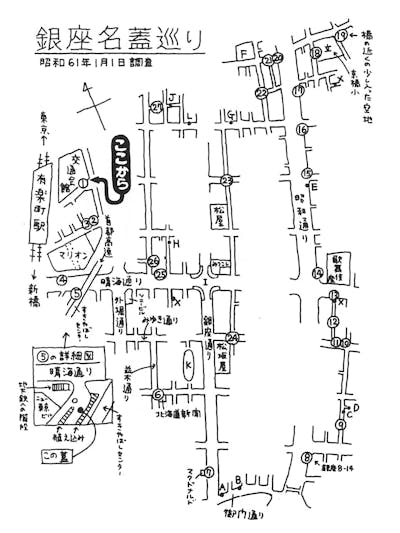

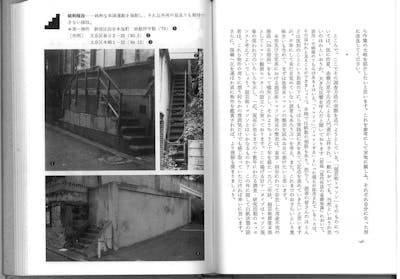

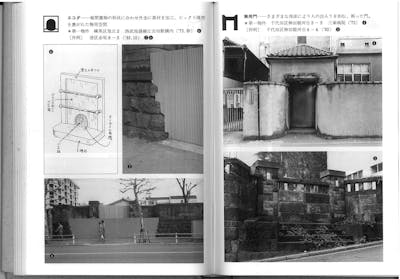

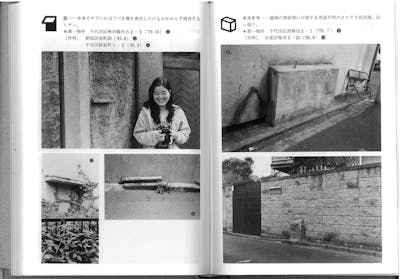

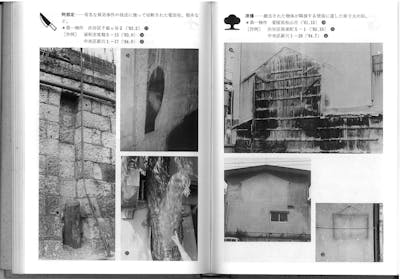

Thomasson typology. From Rojō kansatsugaku nyūmon [Street Observation Studies Primer] eds. Genpei Akasegawa, Terunobu Fujimori, and Shinbo Minami (Tokyo: Chikuma Shōbō, 1986).

Well, for street observers, art is not an enemy, but something from the past. Of course, because art is one of our nostalgic hometowns, we may visit several times a year to relax, but that hometown is far from the prickling sensations of the modern city. We may want to go back there when we get old, but while we are still healthy we prefer to be on the city streets.

Here I will here point out the differences between the “father” (art) and “child” (street observation).

In art, there is an author who creates the artwork, and this artwork is jammed with the spirit and thought and aesthetic sensibility of its author. That is what is called an artwork. An artwork is something for aesthetic appreciation (鑑賞, kanjō) in an art museum.

However, in street observation, our eyeballs are directed toward manhole covers, Thomassons, fire hydrants, building fragments, television sets converted into chicken coops, and such things are not for aesthetic appreciation, that is to say, they are not to be evaluated (鑑, kan) — using precedents to provide illumination and allow judgment — or to be relished (賞, jō). Because an artwork is an embodiment of the intentions of its author, it can be evaluated and relished, but unintentional things that are not filled with thought or spirit, like a manhole cover or the stump of an electric light pole, are called nothing more than objects, and these objects are not to be appreciated, but to be observed.

Of course, I don’t mean to say that observation is of a lower order than appreciation. In the act of observation, as may be understood from the typical summer vacation homework assignment for kids, to “Observe the Morning Glories,” there is an inherent scientism. And this is not the scientism that plunges into the invisible realms of contemporary advanced technology and electronics, but is merely a “child science” apprehensible with anyone’s eyeballs. Leaving the theory of child science to Akira Asada,14 well then, if the word observation is grasped in that way, it may be understood as being just as powerful as appreciation, those being the two most important activities of the eyeballs.

If so, well then, which is more powerful: the aesthetic appreciation of artworks in the world of fine arts, or the observation of items in the streets?

Thomasson typology. From Rojō kansatsugaku nyūmon [Street Observation Studies Primer] eds. Genpei Akasegawa, Terunobu Fujimori, and Shinbo Minami (Tokyo: Chikuma Shōbō, 1986).

I have no reluctance to acknowledge the overwhelming predominance of art appreciation at the moment, but nowadays the visitors to art museums are becoming elderly, so I have often heard, and perhaps art museums have become homes to art for grandpas, grandmas, and aunties. Replaced with street observation, this would be rejuvenated by young boys and girls. It’d be harsh if that were to be dismissed as merely infantilization, but anyway, youths are burning with far more curiosity about the wondrous items rolling along the side of the road than about Western masterpieces such as Van Gogh’s Cypresses and Millet’s The Angelus, and it is precisely this curiosity about objects that is important now.

But there’s no reason to say that all the arts have become relegated to an audience of grandpas, grandmas, and aunties. For example, there is a domain of pictures that are drawn with the same gaze as that of street observers. These are natural history illustrations. As Hiroshi Aramata15 states, natural history illustrations developed as a descriptive method for natural history, which flourished during the European Industrial Revolution — doesn’t this have a wonderful tone?! — and while these images were drawn as a result of scientific observations of unusual plants and animals and minerals collected while walking across hill and dale, mysteriously they are somehow able to tolerate artistic appreciation. Of course, natural history illustrations are the task of one branch of natural science, so though this might seem essentially the same as the origin of child science, like the “Sketch Journal of Observations of Morning Glories,” in any case, when pursuing an accurate reproduction of a subject there should be no chance for self-expression to intrude, but nevertheless, by some unknown mechanism, flavor is exuded by these pictures as they trickle out of the little boat of science.

Of course, even in Japan there is a lineage of natural history illustrations that flourished in the latter half of the Edo period (1603 – 1868), during which many illustrated books on medicinal herbs and fish appeared. From the beginning of the Edo period onward, many people who picked up a brush had the gaze of a natural history illustrator — the gaze of a street observer — even if they weren’t specialized in natural history illustrations. Jakuchuu, Keiga, Kazan, Hokusai, Gennai, among others, were prolific, but interestingly none of them had received any formal training in the fine arts — the Kano School, the Shijo School, and so on16—and instead had honed their skills through street observation.

Thomasson typology. From Rojō kansatsugaku nyūmon [Street Observation Studies Primer] eds. Genpei Akasegawa, Terunobu Fujimori, and Shinbo Minami (Tokyo: Chikuma Shōbō, 1986).

Hinako Sugiura17 is a modern manga artist in sympathy with the gaze of these Edo-period street observation painters, but it is a very interesting fact that she stepped out of historical research on the natural history illustration world, which pursued accurate reproductions of the subject, into the domain of manga. And she’s also a beautiful woman.

Well, given that degree of relationship to the art village, next let’s move on to the relationship with scholarship. This is tough.

Old-style scholarship was the result of a great deal of street observation. To say it happened on the streets is not quite accurate, but it did begin by observing and recording things seen when walking on the streets, or across hills and dales. Tracing biology and geography and ethnology and meteorology back to their origins, we reach natural history as the science of observation of all creation. Along with the fine arts, natural history is a hometown of street observation. However, while the Industrial Revolution marked the raising of the curtain on the era known as modern times, many useful children were born as modern times progressed, but natural history itself perished. At first, these children had life-size bodies that could be apprehended by the eyeballs of ordinary people, but as they became increasingly specialized they quickly became invisible to the naked eye.

Well then, what to do?

After these hypertrophied bodies specialized into fields like engineering and physical sciences, there was nowhere else to go. At any rate, Akitsutsushima18 (“The Land of Abundant Rice”) is now the land of science and technology. However, specialization in the field of humanities, unrelated to commerce, might take a short break and become available for reversion to natural history. Once again, we begin to observe places on foot. If the term Street Observation seems excessively non-academic, better to call it fieldwork.

Thomasson typology. From Rojō kansatsugaku nyūmon [Street Observation Studies Primer] eds. Genpei Akasegawa, Terunobu Fujimori, and Shinbo Minami (Tokyo: Chikuma Shōbō, 1986).

The reason that Hiroshi Aramata, who could have undoubtedly become a great scholar if times were better, and Inuhiko Yomota,19 who would have received medals if he had been born thirty years earlier, have absconded to do natural history on the streets or research in “empty fields” is undoubtedly to revive their living eyeballs by allowing air from the streets to blow through their own heads, packed as they are with academic knowledge. If the eyeballs die, all thought and literature will come to an end. There is no better training for the eyeballs than the study of natural history.

*

Which is why our own eyeballs have parted ways with the empire of consumption, art villages, and specialized scholarship, and tumbled out on to the streets. Looking around us, we notice that some other eyeballs have also rolled out here.

The eyeballs of the “Space School.”20

These eyeballs have quite mesmerizing pupils, and during these past ten years or so they have produced many famous books, such as City Arcades by Takashi Hasegawa, Text and the City by Ai Maeda, and The Spatial Anthropology of Tokyo by Hidenobu Jinnai. Given that their basis is street observation, just like us, they are clearly our older brothers, but differing on one fundamental point.

This difference is obvious if we walk together in a place near water, such as a canal or river.

The Space School pays attention to the spaces at the water’s edge, the stone walls and stone stairways of the storehouses and breakwaters that line the canals, following the flow of water. Because all these visual impressions are resolved in terms of the order that is latent in such spaces, this order must be deciphered. The devastating techniques of the Space School, such as “reading a city” or “reading a code,” are methodologically similar to semiotics. And what becomes visible as a result of these readings is the order of the good old days. The Edo waterfront was vibrant, the back alleys of the old downtown neighborhoods were wonderful — that kind of thing. The modern era has been blamed for obscuring and disrupting the order of those spaces and building a new order on top. These complaints have enough impact to sway most eyeballs when they see statements like, “the progress of the modern era has superseded the values of the pre-modern era.”

However, alas, our eyeballs are not like that. When walking by a canal, rather than the floating spaces, our eyes are first caught by the broken dolls, scraps of wood, and bottles floating on the surface of the water. Shamefully, we are more sensitive towards objects than spaces. One can understand the predilections of such a gaze by looking at the homework that Bigakko21 student Shinbo Minami22 submitted to Professor Akasegawa23 sixteen years ago.

Because we are preoccupied by objects, each individual object leaves an interesting impression as it passes across our eyes, but no trace of an overall order remains on our retinas. Rather than the spaces, we have a direct reaction to the expression of the individual entity as a thing, so let us call this type of sensitivity “object sensitivity.” In pre-modern times — an era of unified order and unified space — individual items were embedded within the whole, so from the standpoint of object sensitivity, they were not very interesting. They provided only weak stimulation.

Entities that are incorporated into the whole but stick out like art objects are restricted to moments of deviation from the overall order. So maybe, to the extent that an entity projects from a space — which is another name for visualization of the overall order — it becomes an object.

This can be quickly understood when you set out the things that street observers like to collect. All of them deviate from their original state.

For example, among the Thomasson objects, which deviate from the strongest order in the world, that of utility, you may laugh at the example of the “Pure Tunnel”: despite being a proper railway tunnel, there’s no mountain or hill above the tunnel, it just supports air. Like a manhole, there are things that soberly persist in their utility but sometimes project an expression that exceeds this single-minded usage, and among them are also sad guys that may be exploited and collected. For example, when walking in Kyoto I sometimes encounter a manhole cover into which the word “ME” has been inscribed. That metal cover stuck in the ground murmurs, “A manhole cover am I.”

Thomasson typology. From Rojō kansatsugaku nyūmon [Street Observation Studies Primer] eds. Genpei Akasegawa, Terunobu Fujimori, and Shinbo Minami (Tokyo: Chikuma Shōbō, 1986).

Among these deviations, there are deviations of position as well as deviations of scale. In Kyoto, as well as the famous gardens such as Ryoan-ji stone garden and Koke-dera moss garden, a type of garden called tsuboniwa (spot garden) that almost nobody visits is hiding in the middle of the traffic. Bright green grass grows thick in 10-centimeter-diameter round holes bored into asphalt roads, sometimes arrayed with pebbles, possessing a wonderful elegance.

This type of tsuboniwa in the old capital was first discovered recently, and aroused interest as a new species, but many varieties became known after that, such as inside the hand pump of an old well, inside the small holes in a manhole cover, and in the heel-shaped tsuboniwa that arises in the hollow of a shoeprint left in the wet concrete in front of a love hotel.

However, having expressed a preference for deviations, I want to give a warning here: deliberate deviations and oppositions, such as intentional parodies and novelties, are no good. Because observation is a scientific activity, we always want to engage with the unaltered, natural streets.

To explain why I am emphasizing this point, the reason our eyeballs have bulged onto the streets is that we have become sick of intentional things. In art intended to produce beauty, in avant-garde art intended to demolish beautiful art, in parodies intended to get a laugh, and in products intended only to be purchased, it is the intentional part that we don’t want. Looking around, most entities in the world are full of intentions, which is tiresome. Of course, the entities that exist in the world were all made intentionally, but through observation, we will discover the parts that deviate outside the boundaries of intention. So in this way, given that the creation of an object is possible only through deviations and protrusions from a space, even if the Space School and the Object School are described as brother eyeballs on the same streets, their relationship has become slightly difficult. We don’t want any antagonism, but there is some tension. The Space School conceals in its heart the desire to return to a harmonious integrity, whereas the Object School makes a final gamble on freedom by departing from pre-established harmony.24 A gamble on freedom…that is an exaggerated way of putting it, but to rephrase it more in line with our actual feelings, we wander about the town, and when we discover a good object we begin to gain a sense of freedom, as if our eyeballs are being revived. We feel as if that part of the city has somehow come to belong to us.

Put grandiosely, the Space School is Bolshevik, and the Object School is Anarchist, but will this anarcho-syndicalism versus bolshevism debate now roll out onto the streets…?

In any event, the time has come for people who aim to do observation on the streets to stand in front of a mirror and check whether the color of the irises of their own eyeballs is red or black. Testing myself, I’m in trouble: my right eye is bright red, and my left eye is jet black. Perhaps most people have a mixture of red and black, and the question is in which direction the mixing ratio leans, but far exceeding the timid question of ratio among ordinary people is Joji Hayashi,25 who has one-hundred-percent pure, unadulterated black eyeballs. The very reason we wanted to raise this banner is, in fact, that on 23 January in Showa year 60 (1985), somewhere near the entrance gate of Toshima Park, I was confronted with this person, who can only be described as the god of street observation. I may have carelessly blurted out the heavy terms Anarchist and Bolshevik in a world of eyeballs, but having blurted, it’s better that we develop this into a worldview.

Looked at with the eyes of a street observer, everything on the street is contained in the single word jibutsu (事物, thing). The world of the streets comprises both “events” and “entities.” The word jibutsu can be divided into ji (事, event) and butsu (物, entity), and attaching the character kudan 件 to each concrete jibutsu gives the terms jiken (事件, incident) and bukken (物件, object). There are somewhat disreputable characters dealing with each of these specializations; jiken (incidents) are dealt with by private detectives who set up an office on the second floor of a tenant building, whereas bukken (objects) are dealt with by real-estate agents running a shop on the first floor of that tenant building — and that may be the reality, but it is a sad reality if we hear a noble word like bukken, not to mention jiken, only when it issues from the mouths of middle-aged real-estate agents. Now that the word bukken has been debased into business jargon for “property,” we want to reinstate its original meaning of “art object” and once again to place it in a brotherly relationship with jibutsu (thing).

Street observers focus exclusively on objects, but, in fact, behind our eyeballs, we are always conscious of incidents. It may be said that we prefer to observe objects that give a sense of the incidents behind them. We search for objects with the eyes of detectives specialized in handling incidents. For example, as with the first known Thomasson object, the “Pure Stair” attached to the Shoheikan building in the Yotsuya district of Tokyo, also known as the “Yotsuya Stair,” undoubtedly the discoverer instantly caught the scent of an incident there. Of course, the issue is not whether there actually was an incident, but it exuded a scent that suggested it wouldn’t be strange if there had been some kind of incident. It is the same with the stumps of electric light poles known as the “Sada Abe Type.”

In the waterfront examples, even if we sense the spaces while standing on the banks, there are no signs of incidents because these spaces are the product of a harmonious state, but, on the other hand, the bottles, dolls, and fetuses that we see floating by are redolent with the scent of incidents.

The Architectural Detectives focus solely on Western-style buildings for the same reason: in the spaces of a Japanese town, a Western-style house is an alien substance that becomes an art object, and, as a result, incidents may easily inhabit its structure. The hiding places in the children’s novel Kaijin nijū mensō (The Fiend with Twenty Faces)26 by Rampo Edogawa27 are always located in old Western-style buildings.

*

Well then, our street observation has fine art and natural history as its nostalgic hometowns, modernology as the mother from which it was born, and it grew up to become a discipline detached from academia, fighting the empire of consumption, and yet, on a separate bloodline from its siblings engaged in the study of space, we have become aware that it’s a lonely individual standing trembling in an unknown place. The apex of the era, or the edge of a precipice — where in the world is this!

1986

In the sky is Halley’s Comet.

On the ground are the street observers.

Under the ground are the subterranean dwellers.

Genpei Akasegawa photographing a tsuboniwa (spot garden) in a manhole cover, in 1986. From Kyoto Omoshiro Watching (Tokyo: Shinchosha, 1988).

Terunobu Fujimori, “Rojō kansatsu no hata no shita ni” [Under the Banner of Street Observation], in Rojō kansatsugaku nyūmon [Street Observation Studies Primer], eds. Genpei Akasegawa, Terunobu Fujimori, and Shinbo Minami (Tokyo: Chikuma Shōbō, 1986), 6 – 22.

Translated from Japanese by Thomas Daniell with Yuki Solomon.

Details of people, publications, and cultural phenomena that would be known to most contemporaneous Japanese readers are given in new footnotes.

Review

By Thomas Daniell

The publication of the book Rojō kansatsugaku nyūmon [Street Observation Studies Primer] in 1986 marked the founding of the Street Observation Society, a small group of Japanese eccentrics with a shared interest in searching the city streets for moments of beauty, interest, or humor in overlooked places and objects. Each of the founding members had long been engaged in such activities, but the creation of the society allowed a fertile merger of disparate yet sympathetic personalities, histories, methodologies, precedents, and obsessions. The two key protagonists were Fujimori, an architectural historian, and Genpei Akasegawa, a conceptual artist and writer. During the 1970s, while still a graduate student in architectural history, Fujimori had founded the Architecture Detective Agency, which comprised a small group of friends who searched for and documented the provenance of minor Western-style buildings in Tokyo and, eventually, throughout Japan. Around the same time, Akasegawa had begun identifying and categorizing the Duchampian “readymades” he found in the streets. He was fascinated by objects that had lost their original usefulness but inexplicably were still being maintained, which he initially called “hyper-art” but later renamed “Thomassons” in ironic homage to major-league baseball player Gary Thomasson; recruited by the Tokyo Giants on a huge salary yet rarely managing to hit the ball, Thomasson was the epitome of expensive uselessness. Akasegawa enlisted his students at the experimental art school Bigakko to found a group he called the Thomasson Observation Center. One of these students was Shinbo Minami, whose homework assignments included a deadpan report on riverside trash.

As well as being founding members of the Street Observation Society, Fujimori, Akasegawa, and Minami were co-editors of the primer, for which they invited in a number of likeminded individuals, notably Tsutomu Ichiki, who had been amassing a huge collection of fragments salvaged from demolished buildings, and Joji Hayashi, a bizarre individual who finds everything worthy of close attention and orderly documentation; he glues train ticket chads into albums, places pebbles that lodge in his shoes into small bottles, all carefully dated, and has famously taken thousands of photographs of manhole covers.

This interest in commonplace objects has a long history in Japanese aesthetics and material culture, but its modern manifestation begins with Wajiro Kon (1888−1973), an architecture professor at Waseda University. Kon originated a discipline that he named “modernology” (though he preferred to use the Esperanto spelling, modernologio), a study of changes in social behaviors and living environments as Japan underwent rapid modernization during the early twentieth century. Following fieldwork on vernacular rural dwellings and surveys of the ad hoc “barrack” shelters built by people made homeless due to the 1923 Tokyo earthquake, Kon’s interests began to extend across many unusual themes, few of them directly architectural. He and his collaborators noted the percentages of Tokyo pedestrians wearing Western versus Japanese clothing, catalogued and quantified changing hairstyles and beard shapes, itemized every object in the house of a newlywed couple, diagrammed the groupings of people relaxing in a public park during cherry blossom season (then later the locations of suicides in that same park), and so forth. This was pioneering and serious work, but not without an absurdist sense of humor; the modernologists also documented trivia such as the patterns of cracks in cups found in Tokyo coffee shops. The techniques developed by Kon and his colleagues have inspired and influenced subsequent generations of fieldwork by Japanese architects, anthropologists, and sociologists, with a notable resurgence from the 1970s onward. Much of this comprised fieldwork and “design surveys” of Tokyo by Japanese architecture students, but it also included the stark documentary approach of photographers such as Daido Moriyama, the “spatial anthropology” of scholars such as Hidenobu Jinnai, and the “pet architecture” of Atelier Bow-Wow.

By the time Fujimori was writing this essay, modernology had become debased into a catchall term for more-or-less frivolous journalism on pop culture trends. His intention here was to return modernology to its origins in the work of Kon, to specify its debts to art and science, its relationship to “serious” scholarship, its rivalry with other urban observers who focused on spaces rather than objects, and its critical positioning with regard to the accelerating consumerism and economic power of Japan in the 1980s. Fujimori is a witty, exuberant, but difficult writer. His prose mixes scholarly citations with pop culture allusions, uses complex vocabulary in slang phrasing, and is rife with wordplay — puns, rhymes, in-jokes, and etymological analyses of Japanese words. All this has been translated as literally as possible, though, unavoidably, many of the nuances have been lost. Nonetheless, the pleasure and amusement he takes in the mundane, profane world around him should be more than evident.

Notes

1

Wajiro Kon (1888 – 1973), architect and educator, founder of modernology (kōgengaku).

2

Kunio Yanagita (1875 – 1962), scholar regarded as the originator of Japanese folkloristics (minzokugaku).

3

By the Great Kanto Earthquake, September 1, 1923.

4

The founding members of the Street Observation Society.

5

A column begun in 1985 by novelist Yasuo Tanaka (b. 1956), published in the weekly magazine Asahi Journal.

6

Kenkichi Yoshida (1897 – 1982), Kon’s collaborator in the development of modernology.

7

An insult that would trigger a duel between two samurai.

8

Sada Abe (1905 – unknown) became infamous in 1936 for asphyxiating her lover then cutting off his genitals with a knife.

9

Genpei Akasegawa is the penname of Katsuhiko Akasegawa (1937 – 2014), artist, writer, and founding member of the Street Observation Society.

10

An annual exhibition of experimental art held in Tokyo, 1949 – 63.

11

A radical art collective founded by Jiro Takamatsu, Genpei Akasegawa, and Natsuyuki Nakanishi, active 1963 – 1964.

12

A term invented by Genpei Akasegawa to describe abandoned, useless objects that may be appropriated as conceptual artworks, which he began doing in 1972.

13

A reference to Marcel Duchamp’s readymade, Fountain.

14

Akira Asada (b. 1957), economist, art theorist, cultural critic.

15

Hiroshi Aramata (b. 1947), author and specialist in natural history.

16

Pre-modern painting guilds based on familial lineages and apprenticeships.

17

Hinako Sugiura is the penname of Junko Suzuki (1958 – 2005), a manga artist and researcher on the Edo period.

18

A name for ancient Japan.

19

Inuhiko Yomota is the penname of Goki Yomota (b. 1953), writer and historian.

20

Researchers and scholars interested in documenting urban spaces.

21

An alternative art school founded in Tokyo in 1969.

22

Shinbo Minami (b. 1947), manga artist.

23

Genpei Akasegawa was Minami’s teacher at Bigakko.

24

A reference to Gottfried Leibniz’s theory of harmonie préétablie.

25

Joji Hayashi (b. 1947), illustrator and essayist, famous for taking photographs of manhole covers, and a founding member of the Street Observation Society.

26

The first installment in the “Boy Detectives Agency” series of novels.

27

Rampo Edogawa is the penname of novelist Taro Hirai (1894 – 1965).

Biographies

Terunobu Fujimori is a Japanese architectural historian and architect. In 1974, while a doctoral candidate at the University of Tokyo, he founded the Architectural Detective Agency, which searched for lost or forgotten modern buildings in Tokyo. In 1986, he joined forces with artist Genpei Akasegawa and others to found the Street Observation Society, in order to document the overlooked trivia and detritus resulting from constant urban development. He is the author of numerous books, notably Meiji no Tokyo keikaku (Planning in Meiji-era Tokyo) (1982), which won the Mainichi Publication Culture Award, and Kenchiku tantei no boken: Tokyo hen (Adventures of the Architecture Detectives: Tokyo Edition) (1986), which won the Suntory Prize for Social Science and Humanities. In the 1990s, he became a practicing architect, achieving international recognition for his eccentric, humorous designs. The Nira House received the 29th Japan Art Grand Prix in 1997, and the Student Dormitory for Kumamoto Agricultural College won the Architectural Institute of Japan Design Prize in 2001. Fujimori was commissioner of the Japan Pavilion at the 2006 Venice Biennale, for which he displayed his own architecture as well as the collective work of the Street Observation Society.

Thomas Daniell is Head of the Department of Architecture and Design at the University of Saint Joseph, Macau, and Visiting Professor at the University of Tokyo, Japan. He holds a B.Arch. with honors from Victoria University of Wellington, an M.Eng. from Kyoto University, and a Ph.D. from RMIT University. A long-term resident of Japan, he is a founding board member of ADAN (Architectural Design Association of Nippon) and is co-curator of Parallel Nippon, a major exhibition of Japanese architecture currently touring internationally. Widely published, he is a two-time recipient of publication grants from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts. He is author of FOBA: Buildings (2005), After the Crash: Architecture in Post-Bubble Japan (2008), Houses and Gardens of Kyoto (2010), Kiyoshi Sey Takeyama + Amorphe (2011), Kansai 6 (2011), and translator of Toyo Ito’s Tarzans in the Media Forest (2011). Also a practicing architect, his design work has been published and exhibited internationally. Email: thomas.daniell@usj.edu.mo