For some time, I have been captivated by a form of writing that has been captivating my email inbox.

Dictionaries define spam as intrusive, internet-mediated advertising — a definition whose interest lies in its suggestion of how much non-intrusive advertising is already around us. Spam is not like this ambient advertising, of course. It is pure intentionality.

It resembles those bloodthirsty rainforest leeches with suckers at both ends that will get to your blood no matter how safe you might feel beneath layers of pants, socks, and sneakers. The “locals” know this very well and go around barefoot or wearing only flip-flops. As for spam, no matter what new filters are available on the market or what new junk-catching rules are invented, it still manages to get through and nest in your inbox.

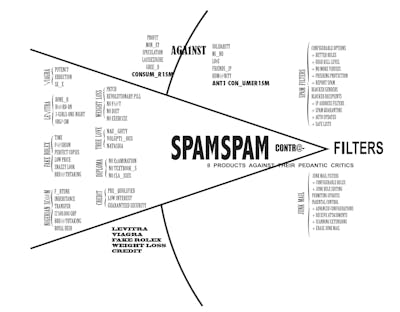

But the issue I would like to get at in this short text is not spam in general but its relation to avant-garde poetry and art, as well as its impact on contemporary poetic and artistic form. For some time I had noticed that certain spam messages that had managed to fool the filters and land in my inbox bore striking resemblance to the poetic and artistic techniques developed in the early twentieth century by avant-garde artists and poets of various sorts. In their form, orthography (if we can speak of such), and syntax, certain spam messages brought to mind the Italian Futurists’ parole in libertà and onomatopoeia, Apollinaire’s Calligrammes, Dada sound poetry, irrational or “transrational” Russian zaum, and the concrete visual poetry of the second half of the twentieth century. This similarity was especially striking a few years ago when spam-filtering rules were not yet as efficient in denying us the perverse pleasure of receiving spam. What kind of relation, if any, can be intuited between the avant-garde radical reformers of literature and the arts and the no less radical spamming techniques of today?

The impact of spam on certain contemporary arts has been long acknowledged. Interestingly enough, though, today the influence of spam is noticeable primarily in contemporary poetry and literature. But the poets — being poets — remain primarily interested in the phonetic, semantic, metaphorical, or syntactic qualities of spam and less in its visual or graphic aspect. For the purpose of making this point more clear, I have appropriated and reconstructed a few avant-garde calligrammes and visual poems, replacing their original historical content with contemporary spam.

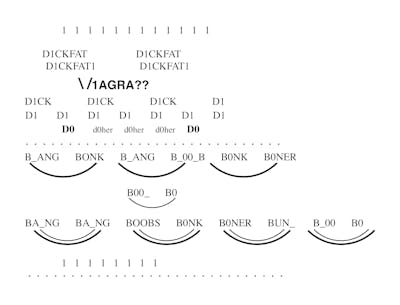

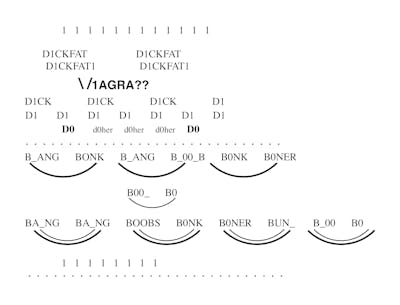

After Francesco Cangiullo, Fumatori, fragment (1914)

After Francesco Cangiullo, Fumatori, fragment (1914)

Spam has not left as notable a mark on contemporary artistic practices as it has on contemporary literature and poetry. In literature, it brought about a range of twenty first-century literary “movements,” including Flarf Poetry, Spoetry, Googlism, and Spam Lit. But the relation between spam and contemporary poetry is not that different from the relation between technologies like telegraphy or radio and Futurist and Dadaist art and literature. Like a century ago, when our avant-garde predecessors looked for inspiration to the new technologies of long-distance communication, using them to free poetic form from the bonds of literary conventions and achieve a much desired modernist literariness, or a material as suchness of language, the poets of today have been looking to botmasters, sysadmins, marketers, pill merchants, hackers, and pornographers — contemporary Don Quixotes, battling spam filters and junk rules incorporated by default in the preference panels of our email applications. Spam’s visual expression and the incorporation of numeric orthography is an outcome of this war against the filters.

After Giacomo Balla, Canzone di Maggio (1914)

After Giacomo Balla, Canzone di Maggio (1914)

In other words, the new forms of textuality that accompany the triumphant march of spam affected contemporary poetic language in the same way in which telephony, telegraphy, or radio influenced early twentieth century literature. Spam played a crucial role in helping bringing literature and poetry back where the avant-gardists always wanted it — to the ambiguities, abuses, intricacies, and slippages of language. But this can also be inferred from simply looking at the spam itself. All that malware, adware, those worms, botnets, trojans, and more are like the digitized and immortalized souls of Marinetti, Kruchenykh, and Balla, saved for eternity on our hard drives, or in the cloud, and deployed through creative spamming techniques to sell replica watches for rock-bottom prices, erectile dysfunction drugs, credit, penis enlargement pills, and various sex services offered by hot Russian girls to all those in whose names the real Marinetti(s), Kruchenykh(s), and Balla(s) once fought to bring about a happier technological future.

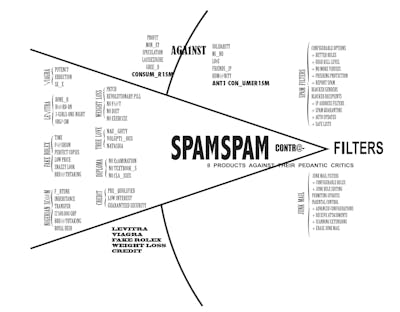

After Marinetti, Boccioni, Carrá, Russolo, and Piatti, Sintesi futurista della guerra (1914)

After Marinetti, Boccioni, Carrá, Russolo, and Piatti, Sintesi futurista della guerra (1914)

The utopian dreams of the happy machinic future that was to come and free mankind from necessity — once envisioned by futurists and constructivists of various sects — seems to have materialized in the dystopian present experienced today in the obscenity of spam messaging. Spam carries rebarbative modernist textuality to the masses. Viktor Shklovsky may have been right when he claimed that artistic or literary heritage is passed down not from father to son but from uncle to nephew. Today, spam is that dashing nephew who was first to realize and take advantage of the potential of modernist abuses and slippages of language. It is the spammers who appear today, perhaps, more radical than the contemporary poets, breaking norms of representation and carrying, across to a wide segment of the consuming masses, their incisive messages. While the Flarfers and Spam Litterers have been catering primarily to the members of the Poetry Foundation and the readers of Poetry magazine, borrowing from spam techniques in order to express their personalities, spammers have followed closely in the footsteps of the historical avant-gardists, adopting — without being aware of it, of course — the more radical principle of aesthetic construction. The artists of the 1910s and 1920s buried the subjective bourgeois category of expression deep under the foundation of modernist art. The new principle of aesthetic construction they proposed — the dialectical shaping of artistic and social material — has re-emerged today in spam, but perverted, as so many other things passed to us by our heroic predecessors. In other words, it is the spammer who has become the true inheritor of historical modernism, the business-savvy digital avant-garde of our late neo-liberal capitalist digital present. They have modeled new forms of radical textuality through constant negotiation of contradictions, constructing and re-constructing, across and in spite of filters and junk rules developed by Google, Apple or Microsoft, the perverse desires of the contemporary digital consumer.

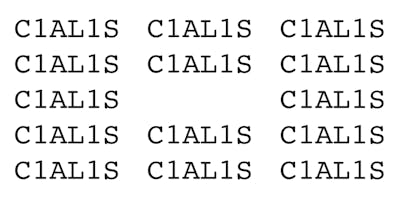

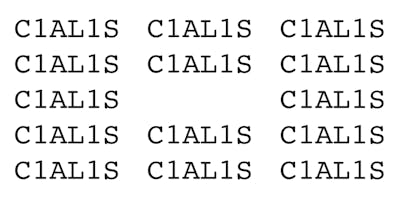

After Eugen Gomringer, Schweigen (1954)

After Eugen Gomringer, Schweigen (1954)

Review

By David Gissen

In addition to the clever acts of appropriation and re-appropriation in Octavian Esanu’s essay, he discovered that translation offers opportunities for exploring the limits and experience of language.

From an instrumental point of view, translation increases the potential number of readers of a specific work across unshared languages and builds new layers of clarity and meaning within a work. A more skeptical opinion of translation — e.g., Walter Benjamin’s — views it as a process that ultimately reveals the way meaning endlessly escapes and reenters language. The “machine” translations by fake pill companies, explored by Esanu, add to the latter interpretation but also create possibilities for understanding the experience of language in translation, particularly in our techno-linguistic time.

Esanu’s collages and the language systems they are built upon enable us to experience language in an indeterminate state. The translation of Viagra into V1@gr@ undercuts the idea of translation as a tool of clarification but nonetheless brings it into new realms of purpose — in this case bypassing the algorithmic gatekeepers of email inboxes. By bringing words out of the context of consumerism and into the realm of art and poetry, Esanu enables us to see the particular character of this language. He enables us to experience something more than its commercial aspect and to began experiencing its form. He enables us to occupy a space of translation and reading between the legible and illegible and between human and machine. That space — like the space of appropriation explored in his essay — remains a critical aspect of a possible vanguard experience of language, one we might all explore more.

- Tags

- literaturetechnologypoetrymodernism

Biographies

Octavian Esanu is currently curator and assistant professor on the Faculty of Fine Arts and Arts History at the American University of Beirut (Lebanon). He researches and publishes on issues related to modern and contemporary art in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, as well as their perception in the Western art historical imagination. He has degrees in fine arts from the Ilya Repin School of Arts and interior design from the State Institute of Arts, Chisinau Moldova. He also earned a Ph.D. in the Department of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies at Duke University. Esanu was the founding director of the Soros Center for Contemporary Art, Chisinau, Moldova (currently KSA:K Chisinau), with which he continues to collaborate, and is part of the editorial collective ARTMargins. In his activities, he seeks a common ground between his artistic, curatorial and scholarly interests. Email: oe11@aub.edu.lb

David Gissen is a historian, theorist, curator, and critic whose work examines histories and theories of architecture, landscapes, environments, and cities. His recent work focuses on developing a novel concept of nature in architectural thought and experimental forms of architectural historical practice. Gissen is the author of Manhattan Atmospheres: Architecture, the Interior Environment, and Urban Crisis (University of Minnesota Press, 2014) and Subnature: Architecture’s Other Environments (Princeton Architectural Press, 2009), and he edited of the “Territory” issue of AD Journal (2010) and Big and Green (Princeton Architectural Press, 2003). His essays have been published in journals such as AA Files, Cabinet, Grey Room, Log, Quaderns, and Thresholds, as well as a wide range of magazines, newspapers, blogs, and books. His curatorial and experimental historical work has been staged at the Museum of the City of New York, the National Building Museum, the Yale Architecture Gallery, the Toronto Free Gallery, and the Canadian Centre for Architecture, among other venues. Gissen is currently an associate professor at the California College of the Arts. Email: dgissen@cca.edu